45th Evacuation Hospital Unit History

WW2 Postcard of Camp Gordon, Augusta, Georgia.

Introduction & Activation:

The 45th Evacuation Hospital was activated at Camp Gordon, Augusta, Georgia (Division Camp –ed) in 1942 (precise date unknown –ed). Camp Gordon was officially opened 18 October 1941 and would become a 56,000 acre training site home to several Infantry Divisions during World War 2. They included the 4th Infantry – 26th Infantry – and the 10th Armored Divisions. The Camp provided a troop capacity for 2,200 Officers and 43,000 Enlisted Men. As early as October 1943, the place also served as an internment camp for Axis Prisoners of War. At the en of the war, it was used as a Personnel Separation Center processing approximately 86,000 men for Discharge (May 1945 – April 1946).

Evacuation Hospitals were organic elements belonging to a Field Army. They were of two types: the 400-bed, semi-mobile, and the 750-bed unit. The 45th Evac belonged to the first category.

Its role consisted in medical support of front line Divisions and carrying out of third echelon medical service. It usually received patients from Divisions, Corps, or Army Clearing Stations. The organization provided as near to the front as practicable the necessary facilities for definitive treatment for all casualties. Patients were retained in an Evacuation Hospital for a few hours to a few weeks depending on the rate of admission, necessity for movement, number of available bed capacity, and the tactical situation in the field.

Overseas Movement:

The organization left Camp Gordon, Georgia at 1000 hours, 7 November 1943. It arrived at its Staging Area, Cp. Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey (Staging Area for New York P/E –ed) around 1000 hours, the next day, 8 November 1943. The remainder of the period was dedicated to training, inspection, paperwork, and preparation for the journey across the Atlantic. The 45th Evac Hosp finally departed Cp. Kilmer at 1900 hours, 16 November for New York. After arrival the personnel boarded a ferry that would take them to pier 86 at 46th Street for embarkation. After boarding the “Aquitania” (Cunard Ocean Liner, requisitioned by the British Government as a troop transport 21 Nov 39, capacity +7,000 troops –ed) at 1030 hours the same day, the ship finally left New York harbor bound for the United Kingdom at 1100 hours, 17 November 1943. Total unit strength at time of departure was 46 Officers, 43 Nurses, and 212 Enlisted Men.

As per T/O 8-581 (1942) the 400-bed Evacuation Hospital had a total strength of 39 Officers, 1 Warrant Officer, 48 Nurses, and 248 Enlisted Men. Vehicles consisted of 2 ¾-ton Ambulances, 9 van type semi-trailers, 2 ¼-ton trucks, 1 ¾-ton command & reconnaissance truck, 2 ¾-ton weapon carriers, 6 2 ½-ton cargo trucks, 4 2 ½-ton 700 gallon water tank trucks, 1 2 ½-ton wrecker truck, and 9 4-to 5-ton tractor trucks. The updated T/O 8-581 (1944) gave following numbers: 38 Officers, 1 Warrant Officer, 40 Nurses, 217 EM, 26 vehicles and 21 trailers.

United Kingdom:

After an uneventful crossing, the fast troopship “Aquitania” reached Scotland, arriving at Greenock, early in the morning at 0400 hours, 24 November 1943. Troops debarked at 1400 hours and almost immediately entrained for Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire, England. They arrived at the site of their new station at 0730 hours, 25 November, where they would remain until 13 June 1944.

After receiving alert orders, the organization was ordered to move to its selected Marshaling Area. The 45th Evac Hosp left Wotton-under-Edge the morning of 13 June, entraining at 0700 hours for Hursley, Hants where it arrived midday. The organization departed 15 June reaching Southampton at 1400 hours. After boarding HMS “Glenearn” at 1720 hours, the Hospital set sail for the Continent.

France:

The 45th Evacuation Hospital landed at Omaha Beach at 1500 hours on D + 10 (16 June 1944).After transferring to smaller landing craft, the personnel were dropped a quarter of a mile offshore. Loaded down with personal gear and equipment, Officers and Enlisted Men made their way to shore.

Hospitals and other medical installations were protected by the Articles of the Geneva Convention. An Evacuation Hospital was supposed to be safe by being set up to the rear of possible harassment by enemy ground action. Although considerable air activity occurred over the Omaha Beach sector as the personnel and equipment awaited debarkation, the only risk to personnel was “ack ack” fire fragments, unexploded AA shells, low level firing of machine guns, and mines. In fact, the intense noise of these activities caused more apprehension than the falling fragments which fortunately caused no casualties among personnel or patients.

Cover of a Booklet dedicated to the 45th Evacuation Hospital and its service years in the E.T.O. This summary was edited and published by Irving Glucoft and Eric Fleischmann, and printed in Bretten, Germany, September 1945.

La Cambe

The general basic blueprint for the setup of the Hospital’s installations which had been planned at Cp. Gordon in the Zone of Interior, and elaborated upon in Wotton-under-Edge in England, had to be rapidly modified when establishing in the fields near La Cambe, France. The original ideas, based upon the 1943 Tennessee Maneuver experience, in addition to the many practical suggestions offered to the 45th Evacuation Hospital by the various units which had already functioned in combat in North Africa and Sicily would not work here, because the situation was totally different. Double tents were erected side-by-side for receiving patients and for their distribution to the pre-operative and shock wards. Separate tents of 40 beds each were designated for:

- early transportables

- duty cases

- non-transportables (head & extremity cases)

- non-transportables (chest & abdominal cases)

Two tents of 40 beds each were designated as medical wards and four pyramidal tents were set up to hold contagious cases. This way all patients who were admitted to the Hospital were always kept under cover: properly segregated in sufficiently large wards where they could be triaged, prepared for surgery, and following operations, properly distributed to particular post-operative wards, from which an efficient method of evacuation could be readily instituted. A sufficient extra number of beds were always kept available to take care of the influx of new patients. When the census ran high, many of the ward Officers had to be loaned out to the OR to assist or to give anesthesia. Such wards as shock, pre-operative, and non-transportable post-operative were in need of the largest number and the best qualified of the Enlisted personnel. By shifting assignments of Officers and EM (as the occasion often required), the organization was able to provide the best possible care to its patients that could possibly be given. In a similar manner, the proper assignment of Nurses and their shifting, supplied the best nursing facilities where they were needed most.

Despite the large number of battle casualties which were admitted, the unit treated a proportionately high percentage of medical cases. They constituted approximately 21% of total admissions. Approximately seventy different specific diagnoses were made, and a number of obscure conditions of the various systems remained undiagnosed, because of the organization’s inability to study these cases completely (lack of facilities and personnel –ed). The latter were then evacuated to the United Kingdom for further study. Careful studies were made of all the patients, both clinically and in the unit’s laboratory. The greater number of the 45th’s patients were returned to duty or transferred to the Convalescent Hospital or the Exhaustion Center, from where they could be sent back to their unit and to duty. These represented 63% of the total number of the medical cases. There was a single death, a patient suffering from acute leukemia, who passed away a few hours after admission. The clinical diagnosis was confirmed after autopsy.

T/O 8-590 Convalescent Hospital, dated 1 April 1942

31 Officers + 192 Enlisted Men

For the most party of the period spent at La Cambe, only two ward Officers were available to handle the post-operative and medical cases. The last few days of July 1944 they were assisted by a third Officer. Despite the difficult work and the long hours needed to observe and care for these patients, special efforts were made to keep accurate and up-to-date records. Mistakes were of course made, but they were of a minor nature. Personnel benefited by them and implemented the necessary improvements that favorably affected the efficiency of the organization’s services.

Because of enemy activity, primarily in the air, the only individual protective measure taken was the wearing of the M-1 steel helmet, but of course this was unfeasable on the wards or in surgery. Personnel were not required to dig trenches or foxholes near their quarters since in any event all personnel went to their duty posts during emergencies. All EM areas were usually placed in the immediate vicinity of a ditch which furnished some kind of cover.

Stations – 45th Evacuation Hospital

La Cambe, Calvados – 16 June 1944 > 24 July 1944

Airel, Calvados – 25 July 1944 > 5 August 1944

Saint-Sever, Calvados – 9 August 1944 > 16 August 1944

Senonches, Eure-et-Loir – 22 August 1944 > 30 August 1944

La Capelle, Aisne – 5 September 1944 > 14 September 1944 (bivouac)

After a certain rest period following the operations at La Cambe, the 45th moved to a new site at Airel, France, where they were immediately greeted with a very large influx of patients. Setting up on 25 July, the organization was kept very busy for almost the entire period during which it functioned at this particular area. It had been planned to erect a double holding tent beside the receiving ward. Here patients with minor wounds were to be held for a compete examination and initiation of therapy until such time as they could be transferred, in the event that the backlog of non-transportable cases would make it difficult to reach these minor cases in a reasonable length of time. However, this had to be dispensed with, when the Hospital was instructed to turn in any excess tentage, and at the same time admit formally for definitive treatment every case which reached the unit’s receiving ward.

Certain modifications were nevertheless carried out. Enlarging the X-Ray department by allowing them two tents hooked side-by-side so increased their efficiency, that greater numbers of patients could now be x-rayed, and had their dry plates with them, long before they were called in for surgery. Allowing three tents for the pre-operative and shock wards, and hooking them onto the main surgeries, and building a surgical prep room in each of these two wards, greatly enhanced the efficiency of these wards, easing the burden which their personnel labored under, until then. Litter bearers too suffered less burden.

In view of the larger number of patients admitted during this period, it was necessary to dispense with ward 2 as a ward in which were previously kept post-operative patients who could normally be returned to duty in 10 days. An analysis of these cases kept at La Cambe indicated that almost all of those who were not ambulatory shortly after operation eventually had to be evacuated. The policy was therefore instituted to transfer all ambulatory duty cases as soon as they reacted from anesthesia and were able to walk about, to the Convalescent Hospital. The remainder were automatically forwarded to ward 1 and evacuated from there, as well as other early transportable cases. Wards 2, 5, and 6 were used as secondary pre-operative wards. Whereas the most serious pre-operative cases not in need of shock therapy were sent from the receiving to the main pre-operative ward, less seriously wounded patients were now fed progressively into wards 2, then 5, then 6. Upon arrival they were checked by a ward Officer, therapy started, and X-rays ordered where indicated. All patients with more serious injuries were transferred either to the main pre-op or shock ward as indicated. A center section of about 30 folding cots in the main pre-operative ward was used as a reserve for patients from wards 2, 5, and 6, and from this section sent to surgery. In this manner, all of the most serious cases were operated first, and subsequently the less serious cases were taken care of in such a way that those who came to the Hospital early were operated on at the earliest feasible time. This method allowed to have the majority of patients operated on in less than 20 hours after their admission to the Hospital.

Aerial view of the 45th Evacuation Hospital at La Cambe, Normandy, July 1944.

It had been planned to use wards 8 and 9 for medical cases; however, in the early days of this phase, ward 9 had to be used for surgical patients. The staff attempted to segregate patients who did not appear to be in need of surgery, such as those suffering from bruises, sprains, blast concussions, etc. The number of available ward Officers was supplemented by 8 Medical Officers from an inactive General Hospital who readily assisted in the work of the ward section.

The Laboratory became a concern when the Laboratory Officer was transferred out of the unit. The internist took over and continued to supervise the work while performing the necessary autopsies on all deaths as required. He also kept the records perfect.

The large number of battle casualties admitted made it necessary to concentrate all medical cases in ward 8. On occasion they would overflow into ward 9. As soon as a complete diagnosis was established, and if the patient was transportable, he was either transferred to the Convalescent Hospital, the Medical Gas Treatment Battalion, sent back to duty, or evacuated as the case required. By this means the Medical Service handled 206 cases, comprising 13% of the total number of patients admitted. Malaria, enteritis, and nasopharyngitis headed the list of definite diagnoses made.

T/O 8-125 Medical Gas Treatment Battalion, dated 11 August 1942

44 Officers + 457 Enlisted Men

The immediate discharge of all evacuable patients left the organization with sufficient empty beds to receive and care for all the incoming patients without any undue delay.

In the Airel operation the 45th Evac Hosp moved somewhat in advance of the Divisional Clearing Stations in that area, and in the bombing to the preliminary St-Lô offensive a stick of friendly bombs fell sufficiently close to the installations to send fragments through several tents. Two of the OR personnel had the extraordinary experience of having their clothes ripped by these fragments but the only casualty was a German PW who suffered a superficial wound of the forearm. After the breakthrough, evidence of enemy activity was negligible. Even though the organization’s vehicles were no longer protected by the Red Cross GC symbols (ordered by Army directives –ed), movements by motor convoys were made without apprehension, a method which was however later discontinued during subsequent movements in the vicinity of the German border.

Saint-Sever

After finishing its first phase of operations at La Cambe, it was felt that the organization had received a rather large influx of patients, treated them amply, and evacuated them promptly. On completion of its second stay at Airel, a proportionally higher daily admission than at La Cambe had been treated and everyone felt that the Hospital had been greatly taxed during its short stay at this new location. Opinions were however quickly revised when the 45th began to receive its first patients at its new site of Saint-Sever early August. In a period of less than 18 hours 400 patients were received. Despite this unusual high census all were kept under cover in the receiving ward and in short order distributed to the proper wards. Triage was handled efficiently due to the fact that the receiving ward was given three tents, set up side-by-side, which gave the personnel more space to segregate patients and more time and opportunity to closely observe them before sending them on to other wards. Also the litter haul was shortened from receiving to pre-op. When the First United States Army decided to return some of the ward tents they had previously taken away, the unit was able to erect a double ward tent (this was ward 7 –ed) beside the receiving tent. Here, cases could in turn be carefully examined by one of the Officers, hydrated, started on penicillin, given sulfonamides where necessary, and re-dressed to check the current status of their wounds.

The excessive number of non-transportable chest, abdominal, head, spine, and orthopedic cases made it necessary to use ward 2 in addition to wards 3 and 4 for these patients. These kind of patients would in the future comprise a rather high percentage of the ones received by the organization. It was therefore decided to use ward 4 for abdominal cases, ward 3 for chest cases, and ward 2 for head, spine, and orthopedic cases. The remainder was left unchanged.

The ward Officers supplemented by the 56th General Hospital did excellent work in enabling the 45th to continue to treat the large census of incoming patients in the best way possible. Their pathologist was of invaluable help in maintaining a 100% autopsy rate. During the last few days spent at Saint-Sever, another ward Officer was permanently assigned to the unit’s staff and helped to care for the post-operative non-transportable patients. The Medical Service cared for a total of 177 cases, comprising 18% of total admissions. The latter were practically all forwarded to ward 8, leaving all other beds in the Hospital available for combat casualties.

Senonches

The 45th Evacuation Hospital arrived at the new site at 1900 hours on 21 August 1944 after a long and tedious trip of about 100 miles from the Calvados region. Immediately after arrival the personnel set to work erecting the Hospital, and by 2200 that same day, sufficient tentage was up to receive patients that night. In view of the fact that patients were not received until noon 22 August, there was ample time to install all the wards and to have them fully equipped to function immediately. The burden upon the Enlisted Men was made heavier, because the organization had lost its 60 PWs, who had previously been a great help in assisting in erection of tentage.

Ward 7, a double tent provided with 40 sets was again set up beside the receiving ward. Here were segregated those cases not too seriously injured. After careful examination by the receiving Officers, they were found not to be in need of further therapy. Their records were then completed and immediately processed through the Registrar’s office and the patients made ready for proper evacuation. As this group comprised quite a large proportion of the total admissions, the routine put in place was very helpful. By giving this group of patients priority in evacuation, the unit was able to get them on their way quickly for definitive therapy further in the rear. It also eased the strain on the few Officers manning the other wards. Maxillo-facial, head, and spine injuries were sent to the pre-op ward where they were put up in special sections assigned for such cases. Also sent here where patients with whom there was a question of non-transportability or who had to be hydrated, receive chemotherapy, have dressings or splints changed before further transportation was advisable. After due care, those of the latter group who could now be moved were directly evacuated; the remainder left to be operated upon, and then disposed of. The shock ward received all intrapleural, intra-abdominal, and non-transportable orthopedic patients, as well as those with other wounds, who manifested evidence of shock.

Ward 1 remained as an early transportable post-op ward; post-op chest cases were sent to ward 2; head, spine, and orthopedic cases went to ward 3; abdominal cases to ward 4. This system was an improvement over previous arrangements and provided better segregation of the different cases and furnished more space and less confusion in treating them. Wards 5 and 6 which were kept in reserve did not need to be utilized to any great extent. Ward 5 was only occupied for one day by 20 post-operative cases mistakenly sent to the organization by another Evacuation Hospital. One of these, a patient in extreme shock, who subsequently died, was retained for treatment at the 45th; the other two were transferred to the Evacuation Center.

The high census of admission made it necessary to utilize wards 8 and 9 for medical cases. 299 such cases were received, constituting 20% of the total admissions. Malaria, diarrhea, and respiratory infections still headed the list, other diseases, such as pernicious anemia, infectious mononucleosis, cerebral hemorrhage were also encountered. The overall proportion of non-ambulantory post-op patients who could return to full field duty within 10 days was almost negligible; the number of non-ambulatory medical cases able to return to duty in 10 days remained small. Diphtheria and meningitis were rare.

Normandy July 1944. Both civilians and military patients are receiving the necessary care and treatment.

A new ETOUSA directive was distributed regarding: “Utilization of Field Hospitals” with instructions to furnish hospitalization on the same basis as Evacuation Hospitals, which raised some questions about the future status of organizations such as the 45th and its ward sections.

Belgium:

Senonches, France, was left 30 August 1944, with the organization moving further east. The 45th Evac departed by motor convoy stopping for a few days in the vicinity of La Capelle, not far from the French-Belgian border, where it set up in bivouac for a well-earned rest period. The period spent at La Capelle after a hectic activity at Senonches was a pleasant interlude for everyone. The most important tents of the ward section were sent out in a limited number of trucks together with other essential parts of the Hospital on the morning of 4 September. In the evening the organization arrived at Ouffet, Belgium, where the group bivouacked.

Baelen

On 15 September the 45th advance party was once more on the move, reaching its final destination, an apparently excellent open field near the town of Baelen, Belgium. The delay in arrival of the remainder of the personnel and equipment (from La Capelle –ed) imposed a heavy and difficult task upon the limited number of EM who accompanied the first group. They had to work real hard to set up the first wards. Starting 16 September 1944, the Hospital began to receive its first patients. Wounded and injured were received directly from the Clearing Stations; non-transportable surgical and medical cases were taken care of, and those patients who could be transported further back were held for either transfer or evacuation. However, due to the difficulty in evacuating them large distances and lack of vehicles, many of the lesser wounded were also cared for by the 45th. After a few days the organization ceased to function as an Evacuation Hospital and really began to function as a Holding Hospital. Patients treated at other medical installations were transferred to the 45th Evacuation Hospital until they could be effectively evacuated. Although the load of patients was markedly increased, the unit was not granted a sufficient number of extra tents or cots to take care of them. Due to this critical situation, every other available tent was appropriated for the ward section. Officers’ recreation tents, American Red Cross tents, Special Services’ tents and even some supply tents were put to use of. Finally an ample supply of extra litters was obtained and these substituted for cots. There was very little or no surgery done. Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted personnel from the operating section were distributed throughout the different wards to give the greatly increased patients’ census the additional care which was required. As there were no sufficient stocks of penicillin, these were reserved for the patients most in need of them. A turnover of more than 600 patients a day in a Hospital which normally cared for only 400, with limited personnel and equipment, made the function of an Evacuation Hospital more difficult. It was evident that changing the scope of an organization without providing the material and the manpower necessary to handle and treat an added patient load affected the operational capability of the organization. In the long run, patients suffered for it.

A total of 304 patients, 20% of all admissions, were cared for by the Medical Service. Having to hold cases of combat exhaustion, the Hospital accumulated a rather large group of them, and except in a few instances, definitive therapy was not instituted until the patients were transferred to the Exhaustion Center (the 618th Medical Clearing Company in Malmédy, Belgium –ed). Neither Officers nor wards were available where therapy could be given. Malaria, upper respiratory infections and diarrhea continued to show a high incidence as in the previous phases of operation. The first case of trench foot was discovered, when a crashed pilot was treated after having wandered about in wet shoes for over a week. Bad weather started interfering a great deal with the daily activities of the Hospital. Rain and mud, of which there was plenty, added to the discomfort of both patients and personnel. Litter bearers became bogged down, absolute cleanliness was difficult to maintain, with mud everywhere. Coal stoves helped by warming the atmosphere and drying the ground within the wards. Working under cover in a building was the only means to overcome some of the difficulties caused by seasonal bad weather.

Stations – 45th Evacuation Hospital

Baelen, Liège Province – 16 September 1944 > 26 September 1944

Eupen, Liège Province – 28 September 1944 > 18 October 1944 + 28 October 1944 > 25 December 1944

Jodoigne, Brabant Province – 31 December 1944 (non-operational)

Spa, Liège Province – 19 January 1945 > 8 February 1945

Eupen

Reaching Eupen, in eastern Belgium, the organization was very fortunate in being able to set up in a building. The continuous rains would have markedly interfered with the Hospital’s smooth function, had it been necessary to remain in the field and under tentage. There were of course some difficulties encountered in attempting to convert High School buildings into a working hospital, but these were eventually met and overcome. The personnel were able to set up 400 beds by utilizing corridor space on all floors including the basement. Ward designations remained the same although their arrangement was adapted in order to utilize the space available to the best advantage. The large auditorium served well for the shock and pre-op wards as well as for the X-Ray department, as they were in close proximity to the Operating Rooms. The early transportable and non-transportable wards were also a short distance from surgery which simplified the distribution of patients to these wards after operation. The large gymnasium was put to good use as well as its adjoining room, serving as an excellent combination of receiving and holding wards. All of the described advantages far outweighed the disadvantages of a long litter haul from the receiving to the shock and pre-op wards. Reserve wards 5 and 6 which overflowed into the corridors of the basement had an extra capacity of 100 beds.

After operating a few days, during which the 45th Evac received casualties for definitive treatment, the unit reverted to being a Holding Hospital. At times very large numbers of patients were brought in, but they were quickly distributed to the proper wards. For the first time in its operational history the medical cases outnumbered the surgical cases admitted. Wards 8 and 9 (expanded into the corridors on the second floor –ed) had a capacity of 80 beds. Here were sent all patients without an established diagnosis; those who could not be transported further; and those who were to return to duty but still required bed treatment. All other medical cases were sent to the reserve wards in the basement, where their charts were rapidly processed and from where they could be rapidly evacuated. The holding ward was used for litter patients who were to be evacuated. When it overflowed, the pre-op and shock wards were used to hold litter cases.

Of the total admissions, 54% were medical. There were 1357 patients, and the number of diagnoses totaled 136. A wide and most interesting variety of cases were seen and 121 cases of trench foot were discovered in all different stages, from mere sensory changes to beginning gangrene. All such patients were carried as litter cases, given tetanus toxoid, started on penicillin and sulfadiazine; their feet were exposed, heels and toes padded, and they were evacuated from the Theater. Upper respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases and malaria were still among the most frequently encountered ailments. Pneumonia, both the lobar and atypical kinds were also encountered. There were a number of benign and malign neoplasms. Among the latter was a case of Hodgkin’s disease and metastatic adeno carcinoma involving the lymph glands. For the first time since La Cambe the Hospital was confronted with two cases of epidemic meningitis. No deaths were recorded during this operational phase.

The surgeons of the OR were available for ward duty whenever they were needed. The Outpatient department treated an unusually large number of cases and saw many soldiers in consultation for Division Surgeons. A roster of surgeons available for such consultations greatly expedited work in this section.

Partial view of the 45th Evacuation Hospital setup in the fields at Senonches, August 1944

The 45th Evacuation Hospital operated far longer than anticipated in Eupen, Belgium. Many more patients were processed with a total of 7707 medical and surgical patients being taken care of. The designation of the various wards was changed in order to better accommodate the different types of cases received. Wards 5 and 6 in the basement were used solely for medical and non-operative surgical cases. The wards on the first and second floors were devoted entirely to the use of post-operative cases. Ward 1 remained the early transportable ward. Because there were many lesser wounded who were not evacuated as quickly as before, this ward was enlarged by setting up an additional 20 beds immediately above it in the corridor of the second floor. One room of ward 3 was converted into a third surgery ward. The other room was used exclusively for patients with vascular injuries. Wards 2 and 4 remained as before, for the care of abdominal wounds and chest injuries. Wards 7 and 8, on the second floor, previously used for medical cases, were converted into post-operative wards. Another room was used for post-operative treatment of head and spine injuries. The other three rooms were used for post-op non-transportable orthopedic cases. The number of vascular and head cases was so large that segregation of these patients greatly facilitated their after-care, both by the Officers and ward personnel. Being housed in a building made things easier, as the inclement weather would have greatly handicapped the organization, were they set up in the field and under tentage. The burden placed upon the EM was made greater by the fact that frequently personnel of the Medical Collecting Company, who were assisting the unit, were called upon for duties elsewhere. By shifting men to wards where they were needed most, the 45th managed as best as they could under the circumstances.

The problem of providing suitable diets for the post-operative patients, especially those in the abdominal ward suffering from gastro-intestinal injuries, became rather acute. Food was served to them, which either they could not eat, or if they did, might have upset their condition. The problem was discussed with the Mess Officer. Subsequently, menus of regular and soft and liquid diets were submitted one day in advance for criticism and copies were distributed to each ward where they could be checked and examined against the food actually served to the patients. The number of reactions from transfusions of ETO Bank blood on the wards was unusually high. There were several very serious haemolytic reactions. The problem was recorded and examination of the blood samples and recorded data were collected in order to try and find and correct the reason for this difficulty.

Of the total admissions, 35% were medical. There were 2172 cases in total. The number of diagnoses totaled 125 cases. Trench foot now headed the list, of which there were 739 cases, seen in various stages of the disease. The milder ones were sent to the Medical Gas treatment Battalion, from where quite a large proportion was eventually returned to duty. Many patients developed swollen, hot, painful feet when exposed to warm air of the wards. If ice was available, it might have helped prevent some of the more serious sequellae. Diarrheal diseases, upper respiratory infections, malaria, and anxiety neurosis followed in this order. There were also 16 cases of infectious hepatitis, 12 of atypical and 3 of lobar pneumonia. Some cases of diphtheria were also encountered, which responded well to antitoxin and penicillin treatment. Eight patients were admitted with a history of methyl alcohol ingestion; 3 died despite treatment, the other 5 never had any symptoms. Two of these showed the presence of methyl alcohol in the urine, while this proved negative for the other three. Toxicological examination of the gastric contents of this patient indicated that he also died of methyl alcohol intoxication.

During the latter part of December 1944, one of the Medical Officers returned to the ZI because of the illness of his child. Meanwhile 2 Officers from the Medical Collecting Company, one of whom took care of the Outpatient clinic, and the other who worked in one of the wards, rendered valuable assistance in helping the organization give care to the greatly increased patient load.

Meticulous care was always given to maintaining a guard detail among the unit’s own Enlisted personnel, armed with M-1 carbines. In friendly territory the locals were given to wandering around the medical installation, usually out of curiosity or goodwill, but sometimes with mischievous intent. When the Hospital used PWs for labor and other small details, they were guarded by someone belonging to the unit’s personnel. When established in Eupen, an alert guard around the area was necessary since the organization was stationed among German-speaking and some Nazi-indoctrinated civilians. Occasional V-1 flying bombs fell in the Eupen area but very few casualties were sustained by military personnel. The billet of the Commanding Officer suffered serious damage from one such incident.

As a matter of fact, not until the start of the German counter-offensive (16 December 1944 –ed) did the unit find itself under fire of enemy air and ground elements. As soon as the news of this enemy attack came through, all prisoners of war were evacuated and all personnel restricted to the Hospital area. At 0530, 16 December 1944, Eupen came under intense enemy artillery fire. One shell burst about 10 yards from the building housing the shock and pre-op wards. An intervening stone wall fortunately caught most of the blast and shell fragments, and no damage resulted to the Hospital. At 2300 hours, 17 December, a gasoline dump east of the Hospital building was hit by a stick of firebombs falling from 150 to 180 yards of the unit. HE bombs or shells then fell within only 60 yards of the northwest corner of the Hospital. The concussion was severe, all windows were blown out, the lighting system was disrupted, and corridors, ward floors, and beds were littered with debris. All personnel had immediately assisted with immediate evacuation of the 166 patients to the basement and shelters and an emergency surgery facility was promptly established in one of the basement rooms. There were no casualties and no undue excitement whatever among personnel and patients, quite astonishing in view of the extensive damage which was evident the following morning. Bomb fragments and blast caused most damage to the north side of the building housing the 45th. The walls of the wards on that particular side, the Registrar’s office, the Laboratory and the Pharmacy showed evidence of splinter damage and cannon fire. The ceiling of the Nurses’ quarters , shock, and pre-operative wards showed evidence of machine-gun fire, and the entire Hospital was filled with miscellaneous rubbish such as plaster, glass, cement, screens, and other parts. An incendiary container was found in front of the Mess Hall; unexploded flares in the storeroom; and an unexploded phosphorus bomb in the street facing the Hospital. Two precautionary measures, as well as extreme good fortune, seemed to have prevented injury to patients. Blankets had been used as black-out screens and barred or arrested the flight of fragments; and at the beginning of the attack beds were pushed to the center of the wards, away from walls and windows. The next day, 18 December 1944, all patients were evacuated and repairs started. Enemy air activity did continue but mostly in the form of aerial observation and occasional strafing of important road junctions. On 19 December 1944, the Surgeon’s Office directed the Hospital to dismantle its installations and prepare all equipment for loading. During the same night, flares but no bombs were dropped. On 20 December at 1000 hours a retrograde movement was made to a new area in Huy, Belgium. A total of 45 2 ½-ton trucks had been dispatched by infiltration and many had already arrived at the new site (Huy), when Headquarters First United States Army ordered all vehicles to return to Eupen, unload, and proceed immediately to Malmédy, in Belgium, to assist in evacuation of the First US Army Medical Depot and the 44th Evacuation and 67th Evacuation Hospitals. Four MC and 2 MAC Officers were also requested by Corps; they left at 2000 hours.

The following morning, 21 December, the Officer dispatched to Malmédy with a detail of 42 EM returned to report 3 of his men missing. All were subsequently accounted for, 2 having been evacuated for wounds caused by enemy MG fire. Only one vehicle was seriously damaged by gun fire. In the meantime the Hospital again prepared to receive patients. The excitement had abated and only American heavy artillery about 1 ½ miles from the installations was active. On 22 December 1944, 218 patients were received and the organization managed to remain open to patients until Christmas day. The Motor Officer now on DS with the Infantry was reported wounded in action although not seriously. On Christmas an egg-nog party and an excellent supper were not in the least disturbed by occasional appearance of enemy aircraft. Bombing and strafing occurred intermittently, but at considerable distance from the Hospital.

30 and 31 of December were spent in moving from Eupen to a new location in Jodoigne, Belgium. The precaution of transporting the Nurses by ambulance was taken because of continuous enemy air activity. The movement of personnel and equipment on the whole was uneventful.

View of the Hospital buildings occupied by the 45th Evacuation Hospital in Eupen, Belgium, October 1944

Spa

It appeared at first glance that difficulties would be encountered in setting up a smoothly functioning Hospital unit in the buildings which were allotted to the organization. Spa became the new site mid January 1945. Access to the building’s upper floors for litter patients would have been almost impossible because of the high, narrow, winding staircases. With aid of some Engineers however, the EM were able to utilize all the available space on the street level floors of the buildings, and litter haul was thus reduced to a minimum. Collapsible field carriers were put to use and from that angle the situation was better than in the previous set ups. The shock and pre-op wards were given ample space and were conveniently located in close proximity both to the X-Ray department and to Surgery. The post-op wards were also suitably situated in relation to Surgery, although not as spacious as they previously were. A separate building was utilized as a medical pavilion. Two garages, close to the receiving ward, were converted into extra wards and were reserved exclusively for trench foot cases. Lighting and heating of these spacious buildings posed a problem, but they were sorted out and taken care of. In general the physical and functional set up of the organization turned out to be as good, if not better, that the one at Eupen.

Criticism had previously been made that post-operative patients received from the 45th Evac had reached General Hospitals with decubitus ulcers. A check of the unit’s records did not bear this criticism out. Close watch was always kept and detailed records made of all observations; there were no instances of decubitus ulceration, and in only one case was an abrasion of the sacrum noted, and this in an incontinent patient who could not be kept off his back for the first few post-operative days. In fact Nurses and Enlisted Technicians were to be commended for the constant and meticulous attention which they gave to their patients.

Total medical cases were 1432, representing some 56% of the total admissions. Respiratory infections were again frequently encountered; both atypical and lobar pneumonia showed an increased incidence. Atypical pneumonia and severe diphtheria with laryngeal involvement coexisted in the same patient, who made an excellent recovery with 200,000 units of diphtheria antitoxin in combination with penicillin. Diarrheal infections and diseases were still present in large numbers, including almost as many cases of bacillary dysentery. Infectious hepatitis was now more frequently seen too. Trench foot however, still headed the list of medical admissions and also frostbite was frequently treated. The shortage of Officer personnel in some of the wards was solved by the return of Officers from the Division where they had been detached to, and the addition of a newly assigned Officer. Three Officers pertaining to an attached Medical Collecting Company assisted in great measure with ward service.

Germany:

The organization’s first move into Germany was expectantly awaited by everyone. Shuttling of equipment to the new site from Spa, Belgium, for a number of days prior to the time the 45th left, greatly facilitated the new move.

Station – 45th Evacuation Hospital

Eschweiler, North Rhine-Westphalia – 5 March 1945 > 22 March 1945

Honnef, North Rhine-Westphalia – 25 March 1945 > 1 April 1945

Bad Wildungen, Hesse – 3 April 1945 > 19 April 1945

Nohra, Thuringia – 22 April 1945 > 28 April 1945

Buchenwald Concentration Camp, Thuringia – 28 April 1945 > 12 May 1945 (operated as Station Hospital)

Nohra, Thuringia – 11 May 1945 (bivouac)

Sankt Wendel, Saarland – 4 June 1945

Schwäbisch Hall, Baden-Württemberg – 14 July 1945 (bivouac)

Bretten, Baden-Württemberg – 22 July 1945 (operated as Station Hospital 1 July > 13 July 1945)

Eschweiler

After arriving at its new location, Eschweiler, in Germany, the organization found itself a new back-breaking job; that of cleaning the rubble and trash within and outside the new building selected for setting up the Hospital. The building had been in use as a civilian hospital but the shattered windows and bombed-out parts posed quite a problem, especially with regard to blackout. With the aid of civilian workmen, repairs were made which enabled the personnel to amply light, ventilate, and blackout the essential wards. The long litter haul from receiving to the pre-operative and shock wards, as well as from the latter to the X-Ray department, could not be avoided in view of the building’s layout. However, a triple ward tent erected beside the receiving ward, and connected to it by an enclosed corridor, was most helpful in disposing hastily of any by-pass cases. An advantage of the new site was the segregation of the various wards in isolated wings of the building. Although most of the rooms taken over were small, there were a number of sufficiently large ones in each wing to accommodate the bulk of patients.

A number of seriously wounded non-transportable patients remained when the 53d Field Hospital moved out and a number of others were admitted coming in from the 51st Field Hospital. Most of these suffered from chest and abdominal injuries. There was a large incidence of complications in both groups, especially the chest cases, and because many of them were running high temperatures, they had to be kept at the 45th Evac for a long time past the usual evacuation period. In the first 8 days of operation, comparatively few patients were admitted, and along these only a few were seriously wounded. Due to the lack of litter bearers however, the ward men were burdened with this duty in addition to their regular ward chores. Reinforcements were brought in by Enlisted personnel of the 115th Evacuation Hospital which greatly lightened their tasks. The organization was fortunate to find many collapsible field carriers (litters on wheels –ed), which were immediately put to good use.

T/O 8-510 Field Hospital, dated 28 September 1943

22 Officers + 18 Nurses + 190 Enlisted Men

Medical admissions fell off perceptibly, with only 160 recorded. 26 cases of trench foot and frostbite still placed these conditions at the head of the list. Infective hepatitis showed a marked increase as 9 cases were received, and 2 EM of the own unit were down with it. There were 7 cases of atypical pneumonia, and 2 of lobar pneumonia, which represented quite a large percentage of the total admissions. Diarrheal diseases were still as frequent as before. Furthermore, there were 5 cases of true dysentery. Upper respiratory infections showed their usual incidence. Two cases of diphtheria were seen, one of whom suffered from paralysis of the soft palate.

On 13 March 1945, the 45th began to function as a Convalescent Hospital, and the unit was re-organized to meet the new problems which arose in connection with such a different organization. Surgery was now reduced to a minimum, leaving sufficient equipment to take care of emergency procedures. All the Medical Officers of the Surgical Service were assigned to convalescent medical or surgical wards. Both Dispensary and Dental departments were enlarged. An Officer was placed in charge of Special Services and a large room released to the ARC workers, in order to provide sufficient diversion and recreation for ambulatory patients and those who were ready to be returned to duty within a few days. An evacuation tent was erected to which all patients who were to be discharged were sent to on the day before their discharge. They received clothes and some basic equipment prior to be transported to their respective units. It should be noted that in contrast to the type of work done while functioning as an Evacuation Hospital, convalescent work afforded the entire unit a period of rest and quiet. In the 5 days during which the Hospital functioned in this manner, 188 patients were received by the Medical Service; and all but a few were returned to duty in a period from 1 to 4 days.

Honnef

Numerous days involving back-breaking work were expended in cleaning and re-organizing the Hospital buildings at Eschweiler and when word arrived that the 45th was to repack and reload its equipment to move further on, a note of disappointment was evident among the Enlisted Men who had been working so hard for so many days. Their enthusiasm suddenly spurted when it was made known that the unit was to cross the Rhine River for the next location. With the growth of the bridgehead (following the discovery and capture of the Ludendorff Bridge –ed) crossing the river in itself was not only a milestone for everyone, but to be the FIRST Evacuation Hospital in the US Armies to accomplish this feat made the event so much more interesting and welcome and exciting. Everyone worked fervently day and night to keep the trucks moving constantly. Meanwhile, Field Hospitals set up in villages near Remagen to receive casualties from the expanding front. The 45th Evacuation Hospital would never forget the first view of the Rhine; the pontoon bridge it crossed and the collapsed bridge at Remagen. 4 more Evacuation Hospitals would follow, while 5 of them clustered near the west bank of the river to receive casualties from both sides of the Rhine. For a time when the advance of First United States Army forces left the 4th Convalescent Hospital far to the rear, the 45th Evac, with another Evacuation Hospital, a Medical Clearing Company, and the 91st Medical Gas Treatment Battalion would inherit the task of holding the lightly injured through brief periods of recovery within the Army area, until the 4th Conv Hosp was able to re-open at Euskirchen on 22 March 1945.

A Field Hospital was still in operation at Honnef, Germany, when the 45th moved in (probably the 51st Field Hospital –ed). Added to the task of cleaning out the remainder of the building, was the work of taking over all the non-transportable cases and assigning personnel to care for them, from the very first day after arrival, 25 March 1945. All this went on while the Field Hospital continued receiving new cases and operating upon them. Fortunately setting up was fairly easy, the building was large and lent itself well for an Evacuation Hospital setup. All essential wards were spacious and this materially helped in getting the most out of the limited personnel available. As the casualty rate was low, not many patients came in. The rapid movement of the combat troops made it necessary to close down after less than 3 days of work and seek a new site for the Hospital. This proved the shortest period during which the 45th worked at any one particular place. Many wondered whether it was worthwhile spending so much energy in cleaning and re-organizing buildings, for the short period the organization was to operate in them.

The large number of post-operative, non-transportable chest and abdominal cases transferred by the still present Field Hospital made these wards the most active. 4 Nurses and 6 Enlisted Men were assigned to each ward for each shift. A fairly large number of these cases, especially PWs, were received directly by the unit. The remainder of the wards were not too busy at that time. There were 67 cases in total on the Medical Service, representing 16% of the total admissions. Upper respiratory and diarrheal diseases were now heading the list. Four cases of atypical pneumonia were encountered, while the variety of other cases was the same as experienced before.

Motor pool of the 45th Evacuation Hospital (school building courtyard), Eupen, Belgium, November-December 1944.

Bad Wildungen

The Hospital set up at Bad Wildungen, a former Hotel, on 3 April 1945, was probably the very best building ever taken over by the 45th Evac. Both from an esthetic and functional point of view, the building not only allowed the organization to accommodate the entire Hospital and its staff under a single roof, but its situation and layout added much to the efficiency of both the professional and administrative departments. The essential wards, such as the pre-operative, the shock, and post-operative non-transportable, had sufficient room to accommodate the markedly increased load of patients without too much crowding and with ample natural light and air to add to the comfort of the wounded and injured. The ORs were on the second floor, one floor above pre-op and shock, but because of the easy approach to the former by wide staircases, this did not appreciably interfere with routine. Although the receiving ward was broken up into a number of small rooms, utilization of the wide corridor space for litter patients overcame this difficulty. The large holding ward adjacent to receiving saved many a headache, in that it was able to hold as many as 100 patients at a time, and it was therefore not necessary to hold slough-off patients in wards which were designated for other special purposes. The new policy of retaining hand cases for 5 days, and the large number of such cases, were well handled by designating a special ward for them adjacent to the vascular ward. With the aid of additional EM the Nurse in charge of this ward was able to care for her own cases as well as those in the hand ward.

The medical cases were segregated on one wing of the second floor and at times there were as many as 125 patients in this service. Separate exits from the holding early transportable and medical wards simplified and hastened the evacuation of patients. The landscaped area surrounding the building (a Hotel –ed) and the wooded hills in its vicinity added a real hospital air to the entire set up, something the 45th had never enjoyed before.

Being the closest Evacuation Hospital to the frontlines, and with other Hospitals far beyond it, it was inevitable that the organization would receive the bulk of the casualties. The personnel were as busy here as they were during some of the active and bitter fighting in Normandy. The excellent cooperation of the Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men, together with efficient organization of the Hospital, enabled the unit to handle the high census of patients quickly and without a hitch. At one time 435 beds were occupied by patients.

The medical service was unusually busy; 715 patients, or 31% of all admissions, were processed through the department. Although upper respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases were still at the top of the list, infective hepatitis with 34 cases, and atypical pneumonia with 16 cases, showed a marked increase over previous periods. A soldier of the 45th Evac was taken ill with jaundice, but was finally diagnosed as a case of sub-acute yellow atrophy of the liver and subsequently evacuated. Because the installation was not set up during the first days of operation to which could be transferred patients with contagious diseases, statistics would show a larger number of these, than had been recorded since the unit’s early operation in Normandy. In total there were 16 cases of parotitis, 3 of them complicated by orchitis. No deaths were recorded on the medical service.

The Laboratory was burdened with a high number of examinations because of the heavy census, but with the extra aid of a civilian technician, and longer hours of work, the personnel managed to overcome the problem. The Laboratory Officer was temporarily transferred to the Surgical Service in exchange for one of its surgeons. Although the unit always seemed enthused about moving forward (and toward the end of the war), some were disappointed in having to leave such a beautiful site and the comforts it provided during off-duty hours.

Nohra

The trip from Bad Wildungen to Nohra, 4 miles west of Weimar, was through picturesque and beautiful countryside never seen before. A number of buildings were available in a wooded area a short distance from an existing airstrip. The largest one was selected for the Hospital, the others to house the personnel. Although the buildings themselves were well constructed, their condition was worse than ever seen before. Fortunately the organization was able to obtain a sufficient number of civilian labor to supplement its own men to clean up the filth and rubble, so that it could open on 22 April 1945.

The general plan of the wards and operating rooms was rather similar to that used at the previous location. The rooms were not as large, but with a little more crowding, it was possible to set up 400 cots. The marked reduction of active fighting as well as the long distance from the front practically eliminated the admission of combat casualties. Surgical admissions consisted almost entirely of accidentally incurred injuries. Although medical cases were more numerous, the service worked slower than before. There were 141 cases, 59% of total admissions. Infectious hepatitis and atypical pneumonia ranked high. At one time the 45th Evac Hosp was advised that it would receive 400 extremely malnourished and weak recovered American PWs (RAMPs –ed), so the Hospital set up was immediately organized to handle this large influx of patients. But though everyone planned and waited, admission of these important patients never materialized.

Partial view of the 45th Evacuation Hospital buildings and motor pool, at Spa, Belgium, January-February 1945

By end of April 1945, several Hospitals served both the combat forces and the non-combatants, with admission and treatment of Recovered Allied Military Personnel (RAMPs –ed) and released Displaced Persons (DPs –ed). Medical units involved in this mission included: the 5th Evacuation, 45th Evacuation, 67th Evacuation, 118th Evacuation and the 127th Evacuation Hospitals.

Weimar (Buchenwald)

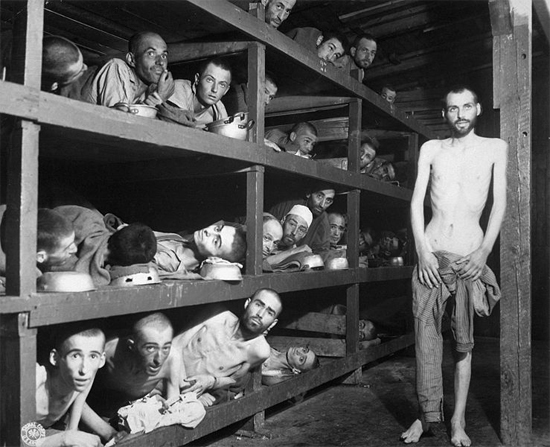

After only 5 days at Nohra, the 45th Evacuation Hospital was instructed to set up a Hospital at the notorious Buchenwald Concentration Camp (liberated 11 April 1945 by elements of the 6th Armored Division –ed).

The reason was that when KZ Buchenwald was liberated a problem immediately apparent was the care and disposition of several hundred TBC patients under treatment at the camp. It was immediately recognized that these were a source of dissemination of the disease, and from the strict point of view of medical care represented a long range problem. Therefore the processing and evacuation of these patients to a hospital appropriate for their continued care was assigned to the 45th Evacuation Hospital (indeed, the conditions under which the prisoners lived at Buchenwald were conducive in every way to the development and spread of Tuberculosis –ed). Nobody was too enthusiastic about this new mission. Nevertheless, as in every one of the previous operations, Officers and men continued to exert their best effort to the full accomplishment of the mission. For the first time, the Nurses would not accompany the unit; it would function without them, causing extra burden on the Enlisted personnel. At Buchenwald, an even more difficult task was assigned to the organization: the immediate operation consisting of processing all proven and suspected cases of TBC for subsequent evacuation to more permanent quarters at Blankenheim. The critical condition of most of the patients made it necessary to select a particular site on the camp grounds as closely as possible to the prison compound in order to shorten the ambulance haul. Following the camp’s liberation, a medical organization had promptly been put into effect by some of the inmates; among them some physicians with experience in the treatment of TBC. Their patients had been sent to three makeshift hospitals established within the camp. The “old” hospital (holding 32 cases), the “little” one (with 96 cases), and the ‘great” one (holding 116 cases); crowded and filthy places where some kind of standard treatment was carried out insofar as it was possible under the desperate circumstances prevailing in Buchenwald, with little food available, and no relief in sight! In all of these three hospitals the mortality from Tuberculosis was tremendous, and it is probable that of the 50,000 inmates who died, many thousands succumbed to the disease. The 3 hospital groups did not account for all the known cases, as some of the patients had been retained by the different national groups after liberation. This added between 100-150 TBC patients located in the various groups.

The atmosphere of the area was a most depressing one. The state of the available buildings was so deplorable that at first glance it seemed that none could be made suitable to house a hospital. A site was sought to set up the tents but there was nowhere sufficient open space to accommodate them. The only solution was to select 2 buildings which were previously used as Waffen-SS barracks. These had been rendered almost unusable by the former owners before they left and had been sacked and plundered by the recently liberated inmates who swarmed into the buildings after their release. Here again, the personnel energetically undertook the task of cleaning the buildings before they were made suitable for use. One building was to house the Hospital, the other the personnel. A two-table OR was established, with the ground floor being utilized for administrative offices, receiving, X-Ray, Laboratory, Pharmacy, and Surgery. SOP were revised and altered. Most of the patients had not been bathed in months and many of them were infested with lice. Typhus was prevalent and measures had to be taken to prevent its spread. 10 to 15 patients were received every hour. A priority system, based on the emergency care required, the advisability of removal for early continuation of care elsewhere and other considerations, was set up, whereby the patients already in the Buchenwald Camp Hospital were delivered in small groups to the 45th Evac. After preparing the necessary records, the group was taken to the bathroom, where clothes were removed and burned. Each patient was in turn bathed, sprayed with DDT powder and clothed with clean pajamas. He was then taken to the X-Ray department where a chest plate was taken. From here he was then assigned to the ward. With this method only clean, deloused patients entered the wards and subsequent movement for other diagnostic procedures was eliminated. Examination of blood, sputum, and urine were routinely done on all patients. Sedimentation rates were done when patients were afebrile. Laryngeal and bronchoscopic examinations were carried out where indicated.

Ten wards of 40 beds each were installed on the second floor, and a similar number on the third floor. An Officer was assigned to each ward. Moreover each ward had 4 Enlisted Men during the day and 3 during the night (the Nurses were not there during this phase –ed). The staff set up at KZ Buchenwald consisted of the CO assisted by 20 Medical Officers. Lt. Colonel Isidore A. Feder, Chief of Medical Service at the time, instituted an organization which admirably combined simplicity and efficiency of operation. In addition to the Ward Officers, he set up other responsibilities involving a Receiving Officer, a General Internist, an X-Ray Specialist, a Laboratory Chief, and an EENT Chief. Special mention, should also be made of the X-Ray Technicians, the Laboratory Technicians, as well as the Litter Bearers, all Enlisted personnel who did an excellent job. All personnel were instructed in detail as to the precautionary measures to be used; gowns, masks, and antiseptic solutions were made available for each ward. Patients were provided with individual masks and instructed to cover their mouths with them when coughing, being examined, or attended. A sanatorium-like atmosphere was maintained at all times. Mattresses or sufficient thicknesses of blankets to supply adequate padding were provided for each individual cot. Although linen was scarce, sufficient was obtained for all the cots. Arrangements were made with the responsible Mess Officer to prepare three high-caloric, high-vitamin meals daily, and that in addition three in-between-meal feedings of chocolate milk, malted milk, and egg-nog be served. Multi-vitamin pills and candy bars further supplemented the diet.

It is difficult to describe the reaction of the former inmates to their new found freedom and the solicitous care which they received at the 45th Evacuation Hospital. Never before had the organization seen patients in such a deplorable physical state. The ravages of their illnesses and long state of severe malnutrition induced by starvation, physical abuse and maltreatment, combined to form a clinical picture which had been rarely seen in the United States. Under the conditions in which the prison camp physicians worked it was inevitable that many cases should have been mistakenly diagnosed. Of the 600 patients admitted, 433 were found to suffer from TBC; also many had pulmonary pathology which was non-tuberculous. There were 10 cases of atypical pneumonia; 4 of lobar pneumonia; 2 of lung abcesses; 1 neoplasm; 1 thoracic empyema; 1 atelectasis of a lung resulting from an aneurysm of the aorta. Malnutrition in some degree was present in all. In 223 cases it was unusually severe and in 22 cases there was clinical evidence of marked vitamin deficiencies such as pellagra and scurvy. Most of the patients with TBC had widespread involvement of both lungs, with exudative lesions and cavitation predominating in the X-Ray findings. 37 patients had unexplained high temperatures and were later discharged as cases of fever-of-undetermined-origin and returned to the compound for further examination and study. 63 patients had pneumothoraxes artificially induced before they were sent to the 45th Evac. One patient died, with post-mortem examination revealing extensive turberculous involvement with cavitation of both lungs and ulceration of the terminal ileum. The ultimate prognoses indicated that the large majority of inmates were to succumb to TBC in a shorter or longer period, and only a few could be completely rehabilitated. By removing them as a source of infection to the other malnourished prisoners of the concentration camp and making them more comfortable the personnel tried to accomplish their mission. The relief which these patients showed after their long ordeal and period of abuse, suffering, torture and filth in Buchenwald, was ample reward to all personnel involved in this unusual phase of operations.

Other operations were conducted by the 120th Evacuation Hospital who took over one of the SS barracks and turned it into a makeshift hospital. The advantage was that it had latrines and heated showers. However having been ransacked and looted by a number of liberated inmates, all furniture, rugs, and bedding were infested with lice. Personnel therefore had to strip the rooms and scrub the floors with soap and hot water, before being able to occupy the place.Following this action, canvas folding cots were moved in and covered with German or American wool blankets, and German civilians who had quickly been instructed in the use of portable DDT dusters were brought in to dust every incoming patient under his clothing. The recently liberated inmates were carried into the new hospital, stripped and bedded down, while their clothes were burned. After the water system had been repaired by Army Engineers, all patients received a thorough bath after the initial delousing. Before handling the sick and injured, medical personnel doused themselves and the bedding with DDT powder to avoid any further infestation or sickness.

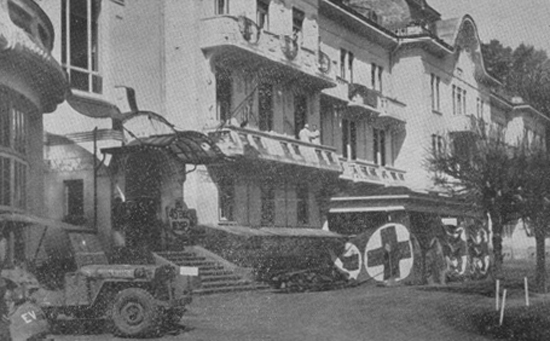

Partial view of the “Badehotel” housing the 45th Evacuation Hospital, Bad Wildungen, Germany, April 1945.

The German Hospital at Blankenheim, about 12 miles from Weimar, appeared to fulfill the requirements for the necessary sanatorium satisfactorily. Four buildings were available for patients, 2 of which were already suitably equipped. There was space for 500 beds, a good basic laboratory was at hand, but X-Ray equipment was missing. Central heating was also available. The current staff of 6 German Doctors, 47 Nurses, and 45 Enlisted medical personnel could be employed for the care of the Buchenwald patients. The 45th Evacuation Hospital remained open from 1 until 8 May 1945, operating as a Station Hospital for servicing the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Roster:

Roster – 45th Evacuation Hospital (16 June 1944 – 8 May 1945)

Officers:

| Lee H. Battle, Jr. | Frank R. Hill | Howard S. Oberleder |

| William G. Birch | Harold C. Hodges (Capt) | Samuel S. Pasachoff |

| Henry A. Boswell (Capt) | Paul G. Hogan | Marden G. Platt (Capt) |

| Bert Bradford, Jr. | Bernard Isaacson | Ernest Sachs, Jr (Capt) |

| Alfred A. Chicote (Capt) | Frank D. Jacobs (Capt) | James G. Sawyer |

| George W. Cleveland, III | Richard P. Johnson | James E. Scott, Jr. (Capt) |

| James J. Coats | Raymond E. Karnes | Billy V. Smith |

| John K. Crawford | Hyman Lebson | Morris Swartz |

| Edward Dierolf | Philip A. Lief | Irvin S. Tanner (Capt) |

| Edwin B. Egli | John N. McEachren | Philip S. Wagner (Maj) |

| Isidore A. Feder (Lt. Col. > CO) | Harry Meyer | Jerome J. Weintraub |

| Louis Fratello (Capt) | Austin W. Miller | James M. Weldon |

| Wallace E. Godwin | Robert J. Miller | Stoughton F. White (Capt) |

| Harry W. Goswick, Jr. | Bernard J. Moore (Capt) | Abner Zehm (Col. > CO) |

| Ben A. Gros (Maj) | Maurice J. Moore, Jr. | George W. Zinz, Jr. (Chaplain) |

Nurses:

| Mary O. Biskup | Frances A. Johnson | Sabina H. Orlinski |

| Edith E. Brooks | Lorene E. Johnson | Julia D. Ramaciotti |

| Margaret Bruchnechter | Harriet M. J. Kreitz | Evelyn E. W. Riley |

| Mary Ann Brugger | Margaret E. Lechner | Nancy H. Rogo |

| Lula L. Churchwell | Margaret W. Little | Gladys M. Rush |

| Evelyn T. Crary | Virginia H. Lloyd | Marion R. Sebring |

| Margaret D. Crim | Barabara Mallett | Susanne F. Sheldon |

| Margaret V. Cunningham | Elon E. Martin | Helen G. Shirley |

| Madeline H. Fazenbaker | Myrtle D. Massie | Hazel G. C. Skinnell |

| Mary S. Ferebee | Alice J. Matthews | Margaret M. Strong |

| Anna B. Gasparovic | Eva H. McLin | Inez E. Terrini |

| Nancy S. Grubbs | Agnes P. McGrath | Elizabeth Thompson |

| Virginia J. Hall | Theresa R. Neill | Zora A. Wilson |

| Dorothy D. Henry | Gertrude A. Nolan | |

| Anne L. Howe | Alva G. North |

Enlisted Men:

| Charles J. Adamski | Stephan Gido | Leonard A. Mott |

| Herbert C. Alder | Stanley A. Given | Walter J. Mullen |

| Harold E. Allen | Howard J. Glass | Julius W. Nelson |

| John B. Altmann | Durward A. Glessner | William Nezgodowitz |

| Carl F. Anderson | Irving L. Glucoft | Michael Nicoletti |

| Georges Auche | John P. Godowsky | Robert C. Nicolicchia |

| George A. Ayres | William H. Gogan | Frank H. Nilsen |

| Alfonso J. Baccaro | Joseph N. Goglia | Elmer A. Niswonger |

| William Balogh | Sidney M. Goldman | Steven M. Oblack |

| Lester Barbier | Joseph A. Gordon | John J. O’Connell |

| Arthur O. Bein | John Gornik | Maurice C. O’Connor |

| Joseph C. Berger | Louis S. Grazier | Theodore F. Orebaugh |

| Anthony Bonanno | James M. Greelish | Michael J. Parichuk |

| Joseph Bonanno | Leon Guervitz | John H. Patton |

| Henry F. Brodbeck | Melvin A. Guenther | Willard P. Parriott |

| Philip J. Bulone | Victor D. Gwinn | John W. Peters |

| Charles M. Burda | Joseph E. Haczynski | Dominick Petrozola |

| Salvatore Calabufalo | Clarence Harootunian | Anthony J. Pierro |

| Andrew F. Campbell | George M. Hartley | Hubert E. Powell |

| Joseph F. Campbell | Ben M. Hawes | Bernard A. Prapopcyk |

| Consiglio J. Caravello | Milton O. Hemness | William P. Pryzgocki |

| Frank J. Carpellotti | Francis J. Hill | Alfred M. Quintal |

| Richard Carugatti | John H. Hiltner | William E. Rafferty |

| Arnold G. Chadwick | David Hochstat | Nicholas Ramminger |

| Odea J. Charest | Robert L. Hoen | James L. Regan |

| Peter Cherkos, Jr. | Donald C. Holland | Harry J. Reimer |

| Denver M. Christman | Vencil A. Honc | Lester J. Riffle |

| Frederick Cohen | Vincent P. Horan | Salvatore Riggio |

| Bruce J. Clark | Ralph Hudspeth, Jr. | Robert Roberts |

| Daniel P. Clifford | Homer M. Huggins | Bennie H. Romary |

| William H. Coleman | Kennet J. Hynous | Leonard Roppolo, Jr. |

| Francis X. Collins | Joseph H. Jessop | Louis A. Rose |

| John B. Conlon | Michael J. Jessup | Francis Russell |

| William Connaughton | James M. Johnson | James W. Russell |

| Charles A. Corandan | Kent O. Johnson | Robert E. Rutherford |

| Sterling B. Cowan | George Joseph, Jr. | Joseph P. Sanfilippo |

| John E. Craig | Harry Kaminsky | Frank J. Scarano |

| Richard J. Cramer | Robert L. Kehoe | Jack Schrager |

| Donald E. Cushman | Stanley W. Kenczka | Tommy Scott |

| Walter J. Cycak | Joseph A. Kennedy | Paul H. Seeber |

| Joseph Czubowicz | Doran L. Kernodle | Gregory J. Segretti |

| Joseph S. Daley | Andrew Kiniry, Jr. | Roland D. Seawright |

| Sterling A. Dalton | Cyril F. Kleyn | James J. Shannon |

| Charles Danish | Joseph Kowalskie | Stephen L. Skarzynski |

| Chester J. Darlak | Walter S. Kucharski | Calvin S. Stan |

| Lawrence E. Davis | Stanley J. Kusic | Edward C. Steinberg |

| Kenneth J. Davitt | Michael J. Laccietelli | Thaddeus M. Stepniak |

| Charles E. Dew | George W. Lamm | Charles B. Sturm |

| Lester S. Diehl | Lester L. Lang | Timothy Sullivan, Jr. |

| Guy E. Dimichele | Edmond D. Laperriere | George R. Truett |

| Lyle M. Domini | Victor P. LaPoma, Jr. | George M. Turnbull |

| Joseph F. Dorocak | Michael Larraia | Waine R. Turner |

| Fred G. Drinkwater | Ralph M. Laserson | Gaylord F. Tuskind |

| Frank W. Drzewiecki | Theodore G. Lemberg | Robert F. Van Alstine |

| Micael Dzialoski | Patrick J. Lennon | Carson H. Van Horn |

| Harold E. Eggleston | Raymond F. Lennon | Emilio Villanova |

| William S. Elder | William H. Linzer | Andrew M. Walko |

| Samuel M. Ellowitch | Charles J. Lord | Lewis A. Wallace, Jr. |

| William G. Ench | Steve Madura | Andrew M. Watkins |

| Steven J. Fallon | Edward J. Mankowski | John A. Watson, Jr. |

| George Fedick | Gordon H. Malsbury | Harold A. Weinberg |

| Joseph A. Fenicle | Anthony C. Mangano | Stanley Whitehead |

| Paul W. Ferguson | Eddie Marshall | Alden F. Wiegert |

| Michael A. Fezza | Marcel Marauda | Robert H. Wilks |

| Sidney Fleischman | Joseph Mauro | Oscar Willerman |

| Eric L. Fleischmann | Peter O. McCallum | Kent J. Wilson, Jr. |

| Richard Fox | William E. McCarter | Everett S. Winchenbach |

| Henry J. Frazier | Daniel F. McGrath | George G. Windell |

| Thomas F. Frerichs | Harold W. McLaughlin | George A. Wingfield |

| Joseph E. Frock | Edward McManus | John P. Yourkavitch |

| James E. Fulcher | Francis A. Meissner | Edward R. Ywasek |

| Richard U. Furlong | Dana M. Messenger | Louis W. Zywicki |

| Pierce B. Gardiner | Herman A. Miller | |

| Walter J. Gartner | Raymond E. Morgan |

Sankt Wendel, Schwäbisch Hall, Bretten

Following a period of partial activities, the organization operated as a Station Hospital in St. Wendel from 1 July to 13 July 1945 under command of Fifteenth United States Army. On 14 July the unit was assigned to Seventh US Army and ordered to move to another location. After remaining in bivouac from 14 to 21 July 1945 near Schwäbisch Hall where most of the time was devoted to the necessary housekeeping activities, maintenance of vehicles and equipment, and a rather extensive athletic program, orders were received 22 July to move on to Bretten where the 45th was to relieve the 95th Evacuation Hospital operating as Station Hospital for US troops garrisoned in this area (primarily the 106th Infantry Division –ed). The hospital was set up in some school buildings which although somewhat damaged by bombs were found very suitable for the Hospital. They offered a total capacity of 130 beds, without undue crowding. Upon arrival, approximately 85 patients were received from the 95th Evac. The main building was divided into two main parts by a connecting bridge across the second floor, and enough space was found in one building to group all the professional services and wards, and in the other building all the administrative offices such as Hospital Headquarters, Registrar, Chiefs of Services, Medical Library, American Red Cross Recreation Rooms, Chaplain’s Office, and Post Office (APO 758). Receiving, Disposition and Evacuation were put on the main floor of the professional building, conveniently combined with a small Dispensary and Operating Room (with 3 tables), the X-Ray Room, and the Central Surgical Supply. The Wards were all set up on the second floor. On the third floor were grouped all medical cases with separate Wards being designated as General Medicine, EENT, Isolation, and Upper Respiratory Infections.

Finale:

The 45th Evacuation Hospital was awarded the “Meritorious Service Unit Plaque” for having successfully accomplished its mission in World War 2.

Redeployment and Readjustment procedures had already been initiated in the Hospital before it was assigned to Seventh United States Army, with the unit being placed in Category II for redeployment to the Pacific Theater. Consequently all Enlisted personnel with over 85 points were transferred out of the unit, and replaced with low-pointers. Four (4) Officers with over 100 points were flown home to the Zone of Interior early July 1945. At the time, none of the ANC Officers nor the remainder of the other Officers had yet been affected by Redeployment. During the period of partial activities, a modified training program was in effect, orientation classes were organized, and recreational facilities were plentiful, keeping morale up. Movies were provided almost every night and frequent baseball games arranged for the afternoons.