Veteran’s Testimony – Barbara Gier 203d General Hospital

Introduction

Barbara GIER was part of a group of Nurses pertaining to the 190th General Hospital temporarily stationed with the 203d General Hospital. Later, she became a permanent member of the 203d. Miss GIER’s reminiscences were assembled into a very impressive volume entitled “In Uniform”.

Barbara Gier’s work has been inspirational in assembling material for this publication. We note that different participants, sharing the same experiences often see and remember different aspects of the same situation. We have asked Barbara’s permission to use excerpts from her work that occurred prior to and continued into her sojourn with the 203d General Hospital.

Here is a brief summary to provide an introduction to her account:

She says: “Looking back over my life, I realize that I was in uniform during 47 years in a profession which provided services to people. I have, in my life and at different periods of time, worn three distinct uniforms in the performance of this service. These were namely – the white uniform of the Hospital Nurse, the blue one of the Train Stewardess Nurse, and the olive drab of the U.S. Army Nurse”.

Barbara entered St. Catherine’s School of Nursing, Omaha, Nebraska in August 1937. This School was associated with Creighton University. Following graduation from the program she applied for and received a position with the Union Pacific Railroad.

Her duties included learning the system of train schedules and transfer points of train car sections from one train to another, depending on their destination. She also assisted passengers with personal needs, monitored minors traveling alone and even kept groups of infants together when a section of cars was transferred from one train to another.

Her employment with the railroad lasted until Union Pacific decided to terminate the Stewardess Service in interest of the war effort which was gaining momentum in the country. It was by then January 1942.

Barbara Gier decided to move to California. This is where her story begins:

Service in the Zone of Interior (ZI):

The European War was foremost in the news and our country was becoming more involved, out of concern for Europe’s welfare. Young Nurses were encouraged to join the Armed Services.

My Nurse friend, Phyllis, and I, wrote to the Army Air Corps for applications and, as she later remarked, ‘it took only a three-cent stamp’ to set in motion the process of our induction into the Army Air Corps. We were assigned to Santa Ana Air Base, near Santa Ana, California and served there for 1 year. We received a commission as 2d Lieutenants and were assigned to the A.N.C. (Army Nurse Corps). The salary that came with the rank amounted to $300.00 per month.

Our duty, as Hospital Nurses, consisted of three shifts – including working day and night. We wore the issue White Cotton Uniform and Cap, White Rayon Hose and White Oxfords. Our Dress Uniform, during the first four months, consisted of a Navy Blue Wool Jacket (similar to that worn by Marines) a Medium Blue Cotton Waist, and a Medium Blue Wool Skirt. Our Cap was canoe-shaped and Navy Blue in color. Stockings were ‘sun-tan’ rayon, and we wore Black Oxfords. We were issued the ‘forest green’ two-piece Duty Dress Uniform, but had not received the directives how to wear it.

Two unidentified Nurses belonging to the 203d pose with their newly issued M3 Gas Masks. This photograph was taken during the unit’s time in England, but regrettably, the exact location is unknown.

In late August 1943 Hospital personnel began their bivouac training. We were portioned off into different groups, including Physicians, Nurses, Aidmen, to be attached to a field unit in maneuvers for simulated combat exercises. Bivouac training lasted one week and was held in Irvine Park, Orange County, California. Participants would wear fatigues, oxfords, soft olive drab safari-type hats, complete with pistol belt and a canteen for water. The training exercise would include instruction and application of the elementary skills necessary for field duty and survival.

Southern California is typically a desert climate, with hot daytime temperatures, and damp cold nights. We wore outing-flannel pajamas and quickly learned, or borrowed, ideas for coping with these climatic conditions. At night we found it necessary to roll-up our day wear and stash it at the foot of our bedding to keep clothing dry. The bedding was fashioned into a bed sack placed on a field cot. During daytime the sides of the tents had to be rolled up, and secured, so as to dry and warm the sleeping area. Fortunately, tents were set up on low wooden platforms and were thus safe from wildlife visitors.

A directive was received requiring parachute training for Air Corps Nurses. The Nurses who elected not to participate would be transferred to the Regular Army. As a result, a number of us were re-assigned. In January 1944, I was sent to Dibble General Hospital, Menlo Park, California. Regular Army Service Women were now wearing the ‘forest-green’ Olive Drab Uniform for dress, with Visor Hat and Army Russet Oxfords.

At Dibble General Hospital I had my first experience in working with men returned from combat duty in the Pacific Theater of Operations. Notable was the fact that these patients evinced severe anxieties, and psychological stress. If the Nurse needed to awaken a patient for medication during the night, she would engage an aidman to accompany her and he would flash a light on the patient’s face. With that kind of provocation the patient might bound out of bed in a defensive action, believing himself to be still in enemy territory and vulnerable to harm. This method was introduced after a corpsman received a blow to the head in a previous incident.

Preparation for Movement Overseas

In September 1944, a number of us received notice of our assignment for duty overseas. The group to which I was assigned, the 190th General Hospital unit, traveled by United Airlines to Camp Myles Standish, Taunton, Massachusetts, near Boston (staging area for Boston P/E). Here we spent 10 days preparing for our departure. We received new clothing and equipment for use in our overseas assignment. Then we marked all government-issues with our names and service numbers.

From this staging area, we were transported by train to a large troopship in Boston Harbor which was destined for Europe. Red Cross personnel were at the dockside to bid us farewell. They served us coffee and doughnuts, and gave each of us a ‘ditty bag’. This was a cylinder-shaped bag of poplin fabric about 15 inches in length, and 20 inches in circumference, with a draw-string closure. The bag held useful items such as a pair of men’s outing-flannel pajamas, washcloths, toothbrush and toothpaste, a bar of soap, candy, mints, chewing gum and one pack of cigarettes. This little bag was a much valued item, and received much use from then on.

We boarded the large ocean-liner, ‘USS America’, and began what was to be a seven-day journey to Liverpool, England. Each stateroom aboard this vessel accommodated 20 women. Bunks were arranged in tiers of three. Each Nurse hung her gear at the foot of her bunk. Individual gear consisted of her uniform, shoes, complete helmet and a musette bag in which her personal provisions were kept. No lights were permitted in the staterooms after dark, so any ablutions or personal tasks had to be attended to while it was daylight.

Our bathing, and small personal laundry, were accomplished in a steel helmet – first a partial spot bath, then only necessary washing of small items of clothing. Water was turned on twice a day, for an hour each time, as it was rationed to conserve the supply. The laundering was done in the nine foot square shower stall of the stateroom, an area only large enough for three bathers at one time. It took speed and efficiency to allow time for 20 people.

The enlisted men were quartered in the lower section of the ship, the cargo deck. Their area was crowded and provided sleeping quarters only, with no real provision for recreation or diversion. On the main deck there was a store in which one could purchase ice cream in small six ounce cartons. The Nurses found pleasure, and pleasant companionship sharing this treat with the GIs. Although we were restricted to our section of the ship, and they to theirs, we managed this friendly association. This natural camaraderie, or kindred friendship, was typical of a bond that firmly united service men and women throughout their service years.

First Lieutenants Carolyn and Putt shown in Winchester, England. Picture taken during the Spring, 1944.

During this voyage, I made the acquaintance of a particular Nurse. She was a joyful, lively person, and being of of a similar nature we became close companions. I will call her Elaine, as I cannot recall her true name. We shared some memorable experiences that month of October, then parted and our paths unfortunately did not cross again. Life was like that during wartime – friendships could be spontaneous, sometimes brief, yet meaningful. Situations could change in a day, or within a week, and with new encounters there were new preoccupations.

We quickly fell into the scheduled routine aboard ship. Groups were assigned definite hours for meals, as well as all activities of the day. After breakfast, the dining room was converted into a ‘recreation’ room, with a bar selling ice cream and cokes. Male and female Officers could sit at the tables and visit, play cards or write letters. Many preferred to be up on deck, taking in the brisk ocean air. Around noon the ship’s orchestra would give us a concert, and we learned to look forward to this welcome daily event. In the afternoon we would sit for hours in the sun watching the zig-zag course of the ship and making new acquaintances. Officers who had field-glasses would share them, and others who had cameras would take little group pictures. Four o’clock in the afternoon started dinner hour, and we would wait in a ‘queue’ again. The Nurses stood four abreast in the lead, with the male Officers following.

About seven o’clock in the evening the ship’s orchestra would play for us in the theater, and then a movie would be shown. I stayed up until at least eleven o’clock, knowing it was best to be really tired before retiring. The longer one lay awake, the more chance there was of becoming seasick. Portholes were well secured until the lights went out around nine o’clock. After this there were dim lights in the hallways and bathrooms. No one was allowed to light a match or cigarette on deck, and MPs were constantly ‘on guard’ for possible offenders. The nights were still dark as death and, if sleep did not come immediately, gave free reign to one’s imagination. My bunk was topmost of a tier of four, and I would climb up in the dark using the edge of other bunks for footing. I knew where my possessions were located. It would be dark yet when we arose in the morning, so we placed our clothing within easy access. our ‘Mae West’ lifebelts were always laid at the foot of our bunk at night.

Certain mornings we had boat-drill, and were instructed to an allotted time and manner for carrying it out. All of us were to appear at our boat station wearing our lifebelts and our belts with canteen.

As the days wore on the ‘chow line’ thinned considerably, but I managed to stay in as the food was too good to miss. We had a Nurse patient in sick bay in a private room, and my turn came to put in a four-hour watch with her. Sick bay was in the lower forward section of the ship, and one felt the ship’s motion more there than anywhere else. The Nurse was receiving phenobarbitol and, knowing that this medication was beneficial in settling one’s stomach, I likewise took some.

England

The night of the eighth day our ship reached the English Harbor of Liverpool and anchored several miles out. We waited quietly in the company of other large vessels. There was a heavy fog at sea, and the numerous vessels waiting there were barely visible to one another in the holding area. I was on deck with other service passengers taking in this memorable experience. The sailors told us that one ship was the ‘Grisholm’, which was bedecked with lights to insure its safety as an ‘exchange ship’.

The next morning everyone was packed and on deck early, feasting their eyes on the British shores. The day was beautiful and much lay in store for us. Our ship moved slowly into the harbor, being pulled by medium-sized tugboats. This, we learned, was the usual practice because the water in the harbor was too shallow to allow large vessels to enter under their own power. We received a grand welcome from the British. At dockside a band played ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ first, and continued with other music selections while we debarked.

From dockside we were transported by troop trucks to a train, to journey to Southampton on the southwest coast of England. From there on we were to cross the English Channel.

The English train was typically European, and somewhat different from ours. The coaches were divided into at least four compartments, with the aisle running along one side. The bench seats in the compartment faced one another, and could comfortably accommodate six people. A sliding door that opened to the aisle could be closed for privacy.

With ‘all aboard’ our train went bounding along at a lively rate, and we could hear the steam whistle announce the crossings. At one station where we stopped, the British Red Cross brought us coffee and cakes through the train. There was an American GI working with them, and we showered him with a hundred questions as he went from one compartment to another. As we continued on our journey we had the pleasure of brief meetings with English children. Their faces beamed with excitement as they raised their arms and formed the ‘V’ for Victory sign with their fingers. We gave them candy lifesavers and warm greetings.

We reached the port of Southampton late in the day and subsequently detrained. Again we were transported by US Army trucks to a large ‘staging area’ near the port. There we were joined with a contingent of American enlisted men, some 500, and together we were to board three LCI boats (Landing Craft Infantry) for the crossing of the English Channel to France. These boats were operated by Navy crews. Nurses were put aboard one of the LCI’s, while enlisted personnel would occupy the other two craft. The plan for the crossing would be timed to coincide with the ‘low-tide’. The Channel did have two ‘high tides’ in 24 hours.

We spent two days of brave attempts at crossing without success. Because of the characteristic agitation of the Channel waters, passage across it required both skill and endurance. The first night, being about midway in the crossing, we remained at sea as it seemed less hazardous than returning to the English shore. The three crafts were roped together for stability, to withstand the rough waters. For the crossing we were to subsist on K-Rations, a dry packaged food used to sustain soldiers in the field. This fare left much to be desired, and we yearned for a hot, tasty meal. I would say, with little else to think of, food was very much on our minds the first day, by the second day, of course, we had a different preoccupation.

There are certain individuals in a group who are daring by nature, or who can be coerced ‘to do the deed’. In this instance hunger, more than courage, was the driving force. So, at the urging of the group, Elaine and I volunteered. We knew the sailors had regular food in the galley on the lower level so decided to ask for a ‘handout’. We discreetly spoke to the Navy Lieutenant in charge of the craft and he suggested we return after dark, when his men on that detail would give us some items. This tactic was necessary for his protection and also served our need to avoid notice by our Chief Nurse. There were two units of Nurses aboard, and a Chief Nurse for each unit. So, at the appointed time, we crossed the open deck in the dark and hurried to the opposite end of the craft. Two sailors emerged from an opening on deck and presented us with two large loaves of bread, butter, two gallons of canned beans, canned peaches and a can-opener. Laden with ‘our prize’ we hurried back across deck where midway we were confronted by the two Chief Nurses! They could not recognize us in the dark and, although justifiably disturbed by our escapade, probably considered the motive of our errand and allowed us to return to quarters. Needless to say the food was enjoyed by all. By the following day we were weary and seasick from the rough waters and had no desire for, or tolerance, of food.

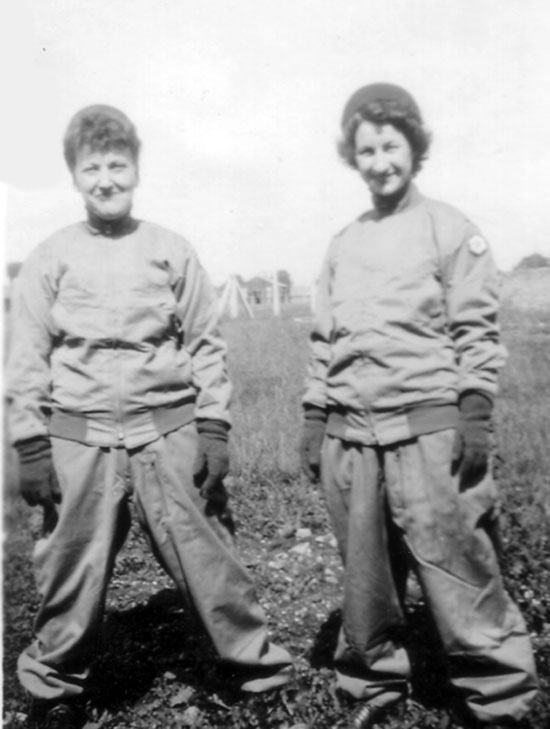

Two unidentified Nurses of the 203d General Hospital. Standing on the right is believed to be Wilmer Putt, but this is unconfirmed. Notice how both ladies wear the Winter Combat Jacket, and Wool Knit “Jeep” Cap.

The Navy crewmen returned the boats to the Southampton Harbor and after debarking, all passengers were now transported by troop trucks to Camp C-5 near Winchester, England. This was an established British Army Base, and we were to remain there for two days of rest and recreation.

While at Camp C-5, Elaine and I met three British Officers and, much to our delight we were given a tour of the city of Winchester and its renowned Winchester Cathedral. I recall a remark made by one that ‘the American soldier was overdressed, overpaid, and oversexed’. We spent a truly memorable day and considered it a real treat to meet ‘genuine Englishmen’. We were back in our quarters by early evening, so had little time to reminisce, as ‘taps’ would soon signal lights out, and tomorrow’s call would come early for the anticipated final crossing of the English Channel – this time in a British vessel.

France

The ‘Antenoir’ was to serve as our transport for the trip across the Channel. On reaching the French coast of Normandy, our ship would anchor within a certain proximity of the shore while the troops disembarked to landing barges. The date was 18 October, 1944.

The elisted men, burdened by heavy equipment and gear, descended from the side of the ship by a wide rope lattice, a ‘scramble net’ temporarily secured to the landing craft. The Nurses were directed to use an adjacent stairway. I recall an incident that day when one soldier lost his hold on descent and fell to the slack between the vessel and the barge, and was injured by the jostling together of the two vessels caused by the rough water. I cried out in anguish at his plight, only to be put down by a young Nurse remarking to me, ‘You’re going to see much worse than this. You’d better not be so sensitive’!

Upon reaching the Normandy Beach, a sandy rough terrain, our eyes took in this part of the French coastline which appeared to be some 1200 feet long and 500 feet deep. The beach was met by a sloping bluff which rose about 300 feet. One could see a low wooded structure atop the hill, or bluff, with an American flag flying nearby. There were remnants of broken landing craft and like debris, jutting up from the water off-shore. Long railroad ties and matting had been lain at some earlier time to provide secure footing in the damp sand and rubble strewn on the beach.

There were exit roads inland, one of which connected with a road paralleling the coast, which in turn branched into the Cherbourg-to-Paris Highway. From this area, personnel were transported by canvas covered trucks to begin our journey in the direction of Paris, some two hundred miles distant. Men and women were separated in their respective carriers. Somehow my friend, Elaine, and I managed to be in the jeep escort which would be the rearguard of the convoy. The enlisted man driver gave us a running account of places of interest along the way. At the start of the journey we made a hasty detour through the perimeter of St. Lô. It was evening and, with the wartime blackout, our view was limited but we were overwhelmed by the musty odor emitting from the area, and our driver quickly regained his place at the rear of the convoy. I would say this was an ‘unofficial tour’, as I am sure we did not have permission to be in this vehicle at all.

Our journey would be interrupted at long intervals by planned stop-overs. One such overnight rest stop was a Field Hospital. There we were billeted in tents – Nurses in a designated area, EM in a separate area. We went to the ‘Mess Tent’ for meals.

The month was October, and the Normandy countryside was cold and damp. Each Nurse had her own cot in the tent but, because of the cold, we slept two to a cot partially dressed. During the night, if we had need for toilet relief we saved ourselves a trip to the designated area by an improvised arrangement. We watched, hidden just inside the tent, as our guard walked his beat and, after he passed, we dashed out quickly to relieve ourselves and were back in bed by the time he returned. Leave it to human ingenuity to invent a solution to a problem.

In the morning we had an early breakfast. The area was bustling with activity and we observed various groups of German PWs occupied in work details. They were quick to take notice of us, and we watched them with similar curiosity. From here we continued our journey toward Paris. That night we stopped at a small outlying train station. While awaiting an early morning departure, we were allowed to take a short rest in a room with bunks for trainmen. When the train arrived, the US Army enlisted men operating the station assisted us in boarding it. They treated us with great kindness and concern for our well-being.

A 1st Lt. of the 203d General Hospital identified as simply “Mac” is pictured standing in the doorway of an M1934 Pyramidal Tent. The picture was taken the during the first day in Normandy.

In due time we reached our final destination. We had been taken to a staging area near Versailles, thirteen miles southwest of Paris. This was a large tented area with lots of military equipment. Our stay at this location was about two days. As luck would have it, we were reunited with the Air Corps Officer we had known in the States. I recall with amazement that he took us to a large communications facility, some distance from this Base. This vital center was well-guarded, and ‘off limits’ to all but authorized personnel. Our visit was brief, but our Officer friend succeeded in contacting an Army pilot friend stationed in England.

From Versailles, France, a group of Nurses and other medical personnel, from our 190th General Hospital, were to be sent on detached duty to the 203d General Hospital, located near Paris. Together we were transported in the standard canvas covered personnel carriers to our assigned destination.

My next recollection is the large General Hospital at Garches, about ten miles west of Paris. It was the former ‘Raymond Poincaré Hospital’, built in 1938 by the French Government. It was located on route N307 between the Paris suburb of Garches and the village of Vaucresson, Department Seine & Oise. The Hospital had been occupied by the German Army just prior to our US Forces taking up residency there.

The US Army’s 203d General Hospital took over the facility on 2 September, 1944. It was the first American Hospital unit to arrive in the Paris area – officially designated so by ComZ, Headquarters Seine Base Section. This large compound consisted of three large modern four-story “H” configurated buildings, designated by the US Army as Building “A”, Building “B” and Building “C”. There was an underground network of tunnels approximately fifteen feet wide connecting the different buildings. These passageways were of cement construction, well finished and well lighted. A circular driveway provided passage in and out of the compound, with all streets of the grounds having access to it. Lining the driveway were several Administration buildings and the residence of the French civilian Superintendent. Enclosing the entire compound was a nine foot high brick wall with only one designated entrance at the ‘gate house’. At this gate US Military Police were on duty ‘around-the-clock’!

Within this compound, in an adjacent area to the left of the gate entrance was ‘l’Hospice de la Reconnaissance’ – a Hospital facility reportedly dating from World War 1. These were three-story brick buildings in a ‘U’ formation, with a Catholic Chapel at the open end. The first floor of these buildings was used to house the US Army Post Office, the Post Exchange, the Red Cross Club, the Cleaners and the Tailor and Barber Shops. The upper floors were used as a Hospital facility for German PW patients.

Other buildings, looking in the direction of the gate house, were the Post Officers’ Club and adjacent to it, the US Army Base Commander’s residence and office.

On the hill behind the new Hospital were three large four-story brick apartment buildings, then designated as quarters for personnel – first, Nurse quarters, second the NCO quarters and third, male Officers’ quarters. When the Germans fled this compound they supposedly disconnected the heating system of these buildings, so for a time the Nurses were given permission to bathe at the Hospital premises until heat was restored. From this area one could walk downhill to the Hospital through a wooded grove, or walk through one of the underground passages.

On the east side of the compound a highway (N 307) ran north and south. The US Army had designated it ‘The Red Ball’ Highway. There was constant traffic of Army trucks and vehicles using this cross-country route to carry supplies to the frontlines. The incessant drone of this convoy of vehicles was quite disturbing until one became accustomed to it.

This Army Hospital was staffed by approximately 250 Nurses together with Administrative Officers, Medical and Surgical Doctors, Noncommissioned personnel, and Technicians! This particular Hospital was the largest US Army General Hospital in the Paris region and also served as an evacuation facility. Because of the workload this entailed, additional Nurses and personnel were assigned to it on detached service, thereby doubling the number of its personnel. At times, assistance was supplied to the staff by elements of the 15th, 180th and 140th Army General Hospitals. Several surgical teams from other units also came in to assist. The Hospital also employed a great number of French civilians during the day, for housekeeping, in the mess department, in clerical positions and as ‘litter-bearers’. These civilian workers were checked on leaving the Base to prevent pilfering of Army goods. Because of deprivation during the German occupation, they were known to artfully stash away needed items in their clothing. Some found an ingenious way to circumvent this search. Such items would be sacked, thrown over the wall and picked up by pre-arrangement with a friend.

The Hospital staff was under the authority of the Base Commander, Chief of Administrative Staff. Next in line for Nurses was the Chief Nurse, Major Nina Piatt. In the Hospital proper there was a ‘Charge Nurse’ for each floor, with at least two ‘Junior Nurse’ subordinates. The Charge Nurse was the Supervisor. She directed all activities, administered medications, ordered laboratory tests and did the paper work at the desk. The subordinate Nurses (of the custodial of which I was one) managed patient care and details of the enlisted personnel. Three aidmen were assigned to a floor, and each floor accommodated 186 patients. A ‘floor’ was divided into wards, differing in size and purpose. Usually a large open ward provided beds for 40 to 60 patients. Smaller wards on a floor were designated for those with more serious wounds, and an enclosed section with dividing cubicles provided isolation for infectious cases.

I was first assigned to the ‘American Wards’. Morning care was accomplished by self-bathing, if able, assisted bathing or complete care by the nurse. Patients and aidmen made beds. At times ambulatory patients voluntarily helped with patient care. They could perform such tasks as shaving bed patients or running errands for them. I described in a letter (home) an incident of ‘patients bathing patients’ and their awkward, but earnest, effort. This must have been one of our very busy times as such was not a common practice at the Hospital. Ambulatory patients usually went to the dining room for meals, whereas patients confined to the wards were served trays. Ward work was completed by 10 a.m. Nurses then changed dressings and the Ward Physician made his rounds and checked any dressing requiring his attention.

Nurses were rotated on three shifts. On night shift there was one Nurse to a floor with two aidmen. There would be a Senior Nurse Supervisor to each building.

I remember when Z had the night shift, I would make a brief stop in the kitchen for coffee. There, in the kitchen area, several German PWs were doing KP duty under guard. I visited with the guard as well as the prisoners. We knew the Germans liked to sing, so I asked them to sing for me. They were reluctant to oblige saying ‘How can we sing when we are away from our loved ones’? But with encouragement and their desire to please, they would break forth with melodious song. True to their German character, they had a natural talent for singing.

During the months of November and December 1944, the Hospital was swamped with wounded, so that for a few days even the corridors were lined with patients on litters as they were brought in. At times there would be 400 admissions in the morning only, and an equal number departing in the afternoon. During the months of January and February the Hospital expanded to 3,360 beds. By June 10, 1945 the 203d General Hospital was relieved of duty by the 36th General Hospital. It had handled 65,613 patients in a ten-month period. It had employed 1450 French civilian workers. US Army personnel had numbered 1,020 which included the attached units.

As the battle front moved deeper into Germany, evacuation of the wounded was funneled in many directions and the system was being fortified by the fresh medical units in forward positions. Some members of the 203d General Hospital were transferred to other Hospitals or to Hospital Trains, while others were directed home (ZI) or to the Pacific War Zone.

Looking back at the enthusiastic effort we gave to caring for our servicemen, I think we also afforded them diversion and entertainment. They delighted in teasing us. One particular Nurse, somewhat older than I, could really hand it back to them in good-natured fun. They dubbed her ‘Half-Track’, alluding to the Army vehicle with tracks on the rear part, which provided good traction in sand. Being with, and caring for them, was so rewarding we looked forward to each day.

Wounded servicemen were brought back from the ‘combat zone’ by Hospital Trains. Army Ambulances, drab green in color with Geneva Convention Red Cross emblems on top and sides, met the Trains at the Gare du Nord, railroad station in Paris. Each Ambulance had a crew of two enlisted men (driver and orderly), both of which were medical aidmen. It required at least 25 Ambulances to accommodate each trainload of patients. Having loaded the vehicles, the drivers followed the instructions of the Dispatch Officer directing their destination.

At the Hospital we received prior notice of an incoming shipment of patients and as they were brought into the Hospital, the litter patients were placed on a folded blanket and secured to the litter by four canvas straps. Casualties were still dressed in their fatigues, with clothing cut away from the area of the wound. Wounds had been dressed at the Field Hospital. Patients had also been tagged (EMT) by those medics with personal identification and name of service unit, as well as pertinent medical information such as type of injury, medication received, vital signs etc. The train staff would add to the medical record enroute.

Sight of the Nurses invariably brought an enthusiastic response from these wounded men. Many expressed their affection and appreciation with their eyes, while others voiced their delight. Busy as this time could be, they took advantage of the brief interval to match states or brave a witty compliment to the Nurses. On one occasion, we somehow acquired 4 Russian patients. They were probably among a group of German Prisoners (East-European volunteers) and as they could not speak English, they did not trust the Nurses because of the language barrier! They had the habit of hiding extra food at the foot of their bed. They also steadfastly refused to be bathed, and we had to enlist an aidman to help us in their care.

Kitchen Staff of the 203d shown in the large complex occupied by the unit in Paris, France. German signs can still be seen in the background; evidence of the buildings’ previous occupants.

In late November, my pilot Officer-friend took me to the ‘Lido’, a Paris nightspot on the Champs Elysées to see the lavish floorshow. The professional entertainers, beautiful girls arrayed in showy, semi-nude costumes held our attention and provoked whistles from the American male audience. In turn, it provoked a look of annoyance toward the Americans from their French counterparts for their lack of discretion. I was quite unprepared for the French practice of shared restrooms at this Club and a bit startled, when awaiting my turn, to see a Frenchman emerge from a booth!

Once or twice a month, Nurses went to Paris for a day of sightseeing and recreation. For us ‘people watching’ was an interesting pastime. At that time public urinals or ‘pissoirs’ were commonplace on various side streets throughout the city. There were two types of these facilities. One was an upright iron wall, slightly concave, where a man could stand and urinate on a grate in the pavement. A constant stream of water from the midsection of the structure served as a means of disposal. Then there was the stationary enclosed urinal used by women. This metal framework was fashioned in a circle, with concealed entrance and exit by design. A woman might park her bicycle, with its open basket containing an unwrapped loaf of bread and a bottle of wine, against a nearby tree and retire to the facility for relief. Only the lower leg of the participant could be seen, as well as the stream of fluid. This activity evoked our interest and, as we watched with stifled amusement and embarrassment, we caught sight of a passerby observing us with astonishment. Feeling ill at ease we quickly moved on our way to other pursuits and places of interest…

We found pleasure in simple things too, a letter from home, bacon and eggs on Sunday morning, a movie, celebration of a birthday or promotion in rank. I read in my letter (home) that we were to have heat in our quarters from 3 to 10 p.m.! This was much appreciated as there had not been heat up to this time.

In order of rotation I was now assigned to night duty for two weeks. This would be a 12-hour shift, 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. without a day off. At the end of the two weeks, I would have a day for sleep, then a free day before returning to day duty. When I returned to work on days, I would be caring for German patients. Because I was of German ancestry, I had an interested curiosity in having a first-hand view of the German people, so I asked for doing duty in the German wards.

The overall plan of care on the German wards was essentially the same as in the American wards, with one exception. At least four of these patients would be assigned to ‘patient care’ and ward duty. These workers were given little caps to wear, made from the stocking tubing used in lining leg casts. The workers were both willing and industrious in caring for the wards. By 8 a.m. the wards were in order, all bed linen changed, and all that remained to be done was the care of the more serious cases. These were bathed by the Nurses. Then came ‘the rounds’ with the dressing cart and in this, the Nurse was assisted by one worker. Next came rounds made by the Ward Physician. Our doctor happened to be Jewish, and he was diligent and kind. One of the workers, Paul Becker by name, was being treated for a non-infectious inflammation of the throat. His treatment consisted of rest only. Paul had little concern for himself and spent his strength in caring for the other patients. The Doctor cautioned him that he would have to be relieved of duties unless he would get needed rest, as his condition was not improving. This Doctor was truly committed to his profession, in a situation that would seem to be a contradiction.

One new shipment included at least a dozen SS Officers. Our workers pointed them out to us, revealing that they had identifying tattoos on the underside of their left upper arm. At first these Officers demanded radios and differential treatment, revealing their arrogant nature. When they observed the care given their countrymen, the attitude took a quick turnabout and they voluntarily assisted in waiting on the more seriously injured patients.

The American MP guards on base, were men on rest periods from ‘combat zones’. We had one MP guard who spoke German. His name was David Sittner and his help was invaluable. We also had a French guard on one shift of the 24-hour guard duty. He was young and, I would say, inexperienced. His uniform consisted of an Army jacket and civilian trousers. The German patients visited with him and busied themselves taking his gun apart and reassembling it. Can you believe it? It showed that these particular patients were content to ‘sit the war out’ with food and shelter, knowing the end of the war was not too distant.

Incoming patients brought updated accounts from the front and this was our major source of war news. One particular German soldier who had been a driver for Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the renowned German general, recounted to us tales of his service.

Fortunately for our mental health ‘all was not work’. We made ready use of available free time in various ways, depending on individual preference. All service men and women enjoyed sightseeing and manyflocked to service-clubs for companionship and excitement. There were museums and historically significant places to visit. We were not allowed passes to visit Paris until November 1944. There was no reason given at the time and we did not question the delay. It was later that we learned of the extensive clean up effort necessary to make the city safe for business and tourism. Paris had only been liberated two months earlier on 25 August 1944. Previous to this, German troops (a force of some 20,000 men) had occupied the city. Half of Paris had been mined by the Germans in their last ditch effort to crush Allied efforts to free it from Nazi occupation. Added to this menace, which would have to be cleared, was the debris of the savage battle within the city at the time of its liberation!

The ‘Raymond Poincaré Hospital’ was about 10 miles from Paris. We could walk to the small train station in the nearby town of Garches, and take the train to Paris. On arrival at the Gare St.-Lazare, we would walk through small business areas to the ‘Georges V Hotel’, Georges V Avenue, off the Champs Elysées. Near the Hotel was a club called ‘The Mayflower’, for Allied Officer personnel. It had originally been a home of a wealthy French Count. The Germans had transformed it into a gambling place. The Allies used it as a social club, and it was operated by the American Red Cross (ARC).

We were also allowed overnight passes. I went to Paris on these occasions. The ‘Hôtel Normandie’ 7 rue de l’Echelle was designated as a leave center for Allied women. Each Hospital was allowed four rooms to accommodate overnight passes. At night there was a doorman at the entrance to the Hotel. He opened a wrought-iron gate for each entry and locked it in turn on closing it. Each person was required to sign in on entering. This Hotel was near the Louvre Museum.

In mid-December we became aware of stepped-up Air Force activity crossing over our area, headed in a north-easterly direction. It was a critical period in which our Armed Forces were engaged in the fierce fighting of the ‘Battle of the Bulge’ in the Ardennes region of Belgium. Casualties were heavy for both the Allies and the Germans. United States Army casualties totaled 77,000. That figure broken down was 8,000 men killed, 48,000 wounded and 21,000 captured or missing.

There was a well-founded rumor at that time that an attempt would be made by German infiltrators to capture a high-ranking American General (Eisenhower ?). The tip-off had actually come from a German Officer taken captive near Liège, Belgium. Tight security was in force in France, extending to Paris. One evening my Air Force pilot friend and I were enroute to a destination near Versailles, France. We were stopped by a road block of Military Police. They challenged my escort, demanding identification and quick responses to various questions. They asked the meaning of typical American slang or colloquialisms and the significance and dates of outstanding US sports that would only be familiar to an American. This technique was used because some Germans spoke English without accent and might avoid detection and slip through our lines.

Members of the 203d General Hospital visit the tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Paris, France. Picture taken 1944.

At the Hospital we had what seemed a never-ending procession of Ambulances bringing in wounded soldiers. The litter bearers were often servicemen on rest rotation back from the front. They were bitter and disheartened by their recent experiences and sometimes demonstrated their feelings by rough or careless handling of German patients. The Head Nurse directing the activity at the entrance to the building for German patients noticed this treatment and censured the litter bearers for being unprofessional. She said, ‘Soldiers, I respect your feelings, but the war ends here. This is a neutral zone’. The Servicemen accepted her rebuke and continued their work without incident. Their patients were, overall, more seriously wounded than those of previous admissions. Their wounds were covered with crêpe-paper dressing, and they were in poor physical condition due to battlefield hardships. Also these Germans were ever younger in age. This was evidence of the plight and adversity of the German troops.

Because of the distressful situation at the battle front, we were restricted to the Base. Therefore a special effort was made to make the holidays meaningful. American Army personnel of the Hospital sang carols to American and German patients. Then 21 patients who requested permission and base personnel who wished to, attended Midnight Mass at the church in the German area.

In early January 1945 we had our first and only snow. Fortunately we now had heat in our quarters full time. In March I returned to work on the American wards. Springtime was very much in evidence and the grounds of the Hospital were beautiful. Up to this time I had been temporarily assigned to the 203d General Hospital. Major Piatt, the Chief Nurse, now informed me that my assignment with this Hospital would be permanent as of February 28, 1945. It seemed to me only a formality as, by then, I had felt a sense of identity with that group. Service people typically formed close ties with their group or unit.

Springtime was an ideal time for sightseeing, so when a trip to visit the renowned ‘Palace of Versailles’ was offered, several of us signed up for it. It was a memorable occasion and we visited the Palace, the ‘Hall of Mirrors’, the ‘Grand Trianon’ and the ‘Petit Trianon’, the numerous historic buildings, and the beautiful grounds.

Even the War news was encouraging, in that victory was now almost assured. But no one was prepared for the momentous news of President Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945! Even the French shared our loss, and expressed their sympathy to us on every opportunity.

Victory:

Our Hospital was busy again. We had news of the German surrender May 7, 1945. A three-day Victory celebration was held in Paris beginning May 11. I was not able to attend but I described ‘eye-witness’ accounts of the festivities in a letter to my mother.

By the end of the war in Europe General D.D. Eisenhower’s SHAEF Headquarters and the War Department in Washington, D.C. had developed plans for redeployment of forces to the Pacific Theater, as we were still at war with the Japanese. The individual soldier’s eligibility for duty or discharge was determined by an elaborate ‘point system’ based on credits for length of service, length of time overseas, decorations, parenthood and age. This operation was quickly set in motion.

The 203d General Hospital had acquired the required 20 A.S.D. Points (accrued service units,) and was eligible to return home to the United States. Those of us who had not been an original member of the unit would be reassigned. In early June 1945, I was reassigned to the 194th General Hospital which was stationed in Paris. Personnel were billeted at a small Hotel, rue des Acacias, a few blocks north of the ‘Arc de Triomphe’. Hospital personnel traveled to and from work on the underground Metro transit system, wearing their Class A Uniform. Service personnel traveled this system without charge. Meals were taken at the Hospital during working hours and at ‘The Mayflower Club’ on off-duty hours. This Hospital was operating in a former Boys’ School in the Neuilly district, northwest of the Arc de Triomphe, and was in service until the latter part of August 1945.

I was delighted to receive such a prime assignment, and to be billeted in that section of the city. Shortly after my transfer to the 194th General Hospital I was also surprised and pleased to be informed of my promotion to the rank of First Lieutenant. My current Officer-friend arranged a little party at The Mayflower Club on a Saturday evening, and I was properly feted at that occasion.

On July 4, 1945, I had the good fortune of seeing General George S. Patton riding in an Army vehicle along the Champs Elysées. He was standing in an open Command Car, being driven in the direction of the Arc de Triomphe. He was wearing an OD Eisenhower Jacket and OD trousers and a helmet, and as was his characteristic style, all ‘spit and polish’ ! His demeanor was one of self-respect and confidence. He appeared to be of medium height and build. The apparent ‘impromptu event’ occasioned by his visit to Paris, seemed to be enjoyed as much by the guest as by the onlookers.

Although this was a trying time for the French people, with their economy in shambles, they showed infinite resilience as human beings. Any excuse justified celebration – an outward expression of their gratitude for freedom.

The 194th General Hospital in Paris seemed to be receiving a predominant number of medical cases at this time. This was probably due to the cessation of the war in the European Theater of Operations, and also because wounded servicemen were being flown directly to Army Hospitals in the United States. We Nurses were distressed by the emotional anguish and outcry of our emotionally disturbed patients. It was depressing to see these broken lives.

By the middle of August our Hospital unit received orders to proceed to Camp Carlisle, near Reims, France. This Camp was a very large reprocessing center and there we would join a contingent of some 1000 Nurses and Red Cross workers. We would be reassigned from this center. I had put aside hopes of a holiday leave applied for in April. So when orders came through for a leave on August 27, I was pleasantly surprised. My two southern friends, Cartha Bartlette and Sara Hamilton, and Z had planned to visit England and Ireland.

We sailed from Dieppe, by an excursion-boat, to New Haven, England where we took a train to London, England. In London we were referred to a Red Cross facility, where lodging was available for visiting service women. The following day we went sightseeing in London. We also acquired the necessary passes to visit Ireland. September 2 we left London by train at 4 p.m. We rode all night through the outskirts of London, along the border of Wales to the southwest tip of Scotland. We reached Stranraer, Scotland early the next morning in time to catch the ‘Empress Queen’ riverboat to Belfast, northern Ireland. We attended a dance at the Allied Officers’ Club. The next morning, we proceeded by train for Dublin, Ireland, where we arrived around 4 p.m. We were directed to a private home where we obtained two upstairs rooms. This accommodation with a private family, provided ‘bed and breakfast’ facilities.

We spent the afternoon of the next day shopping. We visited several jewelry stores and I bought a moonstone ring.

In the evening we had dinner at ‘The Savoy’ and later attended a dance with a young Irishman. The next day, we three girls and our Lieutenant (American) companion spent a pleasant day at Arcklow, walking on the beach. September 7 was the day for our departure and we were given a hearty box lunch for the journey. Approaching the train station we all looked for our passes, in readiness for boarding. It was then I came to the realization that the Captain who had been one of our companions on the journey to Ireland had inadvertently taken my ticket with him. The American Lieutenant suggested a resourceful plan of eluding conductors. The pass was a permit, whereby service personnel traveled without charge. It was a document that had to be presented on request.

Various vehicles belonging to the Motor Pool of the 203d. Of special interest is the second Jeep along in the line, which appears to be that of the unit’s Chaplain.

Image is courtesy of Lois Montbertrand, via her website.

After an eight hour train trip, we reached the Ferry station at Dun Laughaire and I managed to elude detection by moving about and remaining vigilant. However, on the train from Liverpool to London (an overnight trip) I was distracted from my vigilance and in the end had to explain to the conductor that I was unable to locate the item. He concluded (wrongly) that I couldn’t have gotten this far without a pass, so ‘not to worry’! I returned to my companions with a light heart. When we did get back to Paris and checked at the Hotel desk, the two enlisted men on duty told us that they would check on our unit, through the Army Information Service in Paris. They then informed us that the 194th General Hospital had left Paris by train and was enroute to Besançon, France. They directed us to the US Army Transportation Office where we would pick up our orders and our train passes.

When we obtained our orders, we saw that they were dated for September 12, so we had two ‘free days’ to enjoy Paris. September 12 we had an early breakfast and availed ourselves of the transportation provided by the Hotel to the Gare du Nord train station. We then boarded the train for Besançon, France to join our unit. Besançon, was 275 miles southeast of Paris, near the Swiss border. This was a long, tiresome trip, taking seven hours. We arrived late afternoon. The city was surrounded by mountains and very beautiful. We were temporarily billeted at a Field Hospital, assigned duty in the medical section and remained at this Hospital for ten days.

Belgium

On September 22 we left by train for Antwerp, Belgium. As always, when traveling, we were sustained by K-Rations during the journey, so we relished the hot coffee and cake provided by the Red Cross at our stop in Dijon, France. Enroute we slept on the floor of the train car, using our duffel bag as a pillow, because the wooden bench-seats in the train were so uncomfortable. We arrived at Antwerp at noon on September 24, 1945.

Antwerp, Belgium is a port city in northwest Europe. This port had been liberated by the Allied Armies on September 5, and had been in use since November 26, 1944.

The Hospital to which we were attached had been allocated to the use of the Allied Forces, and had been in operation as a General Hospital for at least one year. After a free day to get settled and receive our assignments, we returned to work with enthusiasm. We heard that there was a fairly high number of accident cases, and that surgery was busy throughout the night. We were assigned to the medical section, and it was busy there as well. By the weekend friend Sara and I rated a half-day plus a ‘free day’ and received passes to Brussels, Belgium. Brussels seemed to be a gay, lively city and we enjoyed the sights and the good food. The people seemed aloof and distant, but we attributed their apparent indifference to the language barrier. We had meanwhile grown used to the sociable manner of the French people.

The care of patients went on ‘round the clock’ and there was never a dull moment. We were never at a loss as to how to spend our shared ‘free time’. The weeks seemed to pass quickly because we were busy at the Hospital. By December 1, 1945 we heard rumors that our Hospital unit would soon be leaving Europe and return to the States. On December 4, we were told to start packing our personal belongings. Another unit was replacing the 194th General Hospital and would remain to ‘close out’ our commitment …

Our last day of duty would be December 7. Sunday, December 9, we left by train for Liège, Belgium which would be the first of our stop-overs on the journey home.

Women service personnel were housed in wooden barracks within the walls of an old fortress, called ‘The Citadel’. Each building was an open room furnished with 20 cots and a pot-bellied coal burning stove. This was a sociable arrangement and we were both happy and comfortable in our warm quarters. With time on our hands, my two southern friends, Sara and Cartha, and a Lieutenant Helfin, we decided to visit the city of Liège.

We had heard, from other members in our quarters, that this area of Belgium was noted for beautiful hand-made lace and, too, these people valued the quality of American-made cigarettes. The four of us, bundled in warm clothing, set out for a walk to the city. Two of us carried our ditty-bag filled with cigarette packs which we intended to exchange for lace items at a store, we were told, where such an exchange could be made.

As we approached the city, a chauffeur-driven automobile came into view. The passenger was a three-star General. He addressed us in a cordial manner and offered us a ride to the city. We politely declined, saying we were out to enjoy the fresh air. On his kindly insistence, we were obliged to accept the ride. In the course of the conversation he mentioned he had heard rumors of servicemen ‘bartering cigarettes’ in this area, ‘but, of course, he was not suspecting service women of this sort of thing’. He asked, in a reserved manner, ‘if we had heard such a rumor’? Someone volunteered, ‘Sir, we have been here only two days’. He responded, ‘Oh yes, of course. I am sure you ladies will enjoy the sights of this historic city’.

Then I realized the car was stopping. He assisted us out and we politely thanked the General for the ride. We were now in the area of small craft-shops and cafes. When the driver made a left turn, we supposed they would go around the block and return for a ‘pass by’ to see what shop we entered. So we quickly dashed into the one we had been referred to and peeked out from an obscure side window of the shop. Sure enough, in a matter of minutes, the car drove slowly by and continued up the street. With one person posted to watch at the window, three of us made our selections. The woman shopkeeper, well versed in such privy dealings, closed the transaction in a flash. She opened a lower drawer behind the counter and emptied the contents of the ditty-bags. The deed was done! (whenever I use my three lace doilies these days, I remember the ‘price’ with a twinge of conscience.

“Reno” of the 203d fools around in the sea at Le Havre, while the unit is stationed at Camp Philip Morris in preparation for return to the United States.

We learned our unit would be leaving Liège on December 22, 1945. We arrived in Paris at 8 p.m., where we were directed to board Army trucks. Our convoy of vehicles left Paris at 9 p.m. and drove all night enroute to Camp Philip Morris near Le Havre, France. This camp was very large, and a center of constant activity, with troops arriving and troops departing 24 hours a day. On December 24 we received word that our unit was assigned to leave on the USAHS Jarrett M. Huddleston, a US Army Hospital Ship.

Home Again:

We left Camp Philip Morris at 1 p.m. December 30, 1945 and traveled to Le Havre where we boarded ship. We sailed across the Channel to Southampton Harbor to pick up a shipment of ‘homebound’ patients. We set sail on New Year’s Day at 2 p.m. and our quarters consisted of several large rooms furnished in a double-deck arrangement of bunk beds.

Around January 14 we had rough sailing for a few days and we were directed to wear our Mae Wests! Then we learned that our ship had to ‘stand by’ a sister-ship that had a faulty rudder. Finally we were sailing again and, on January 18th we approached New York Harbor.

As we approached the harbor, a large ‘show boat’ adorned with bright colored bunting, welcomed us home. We could hear the lively sound of music wafting toward our ship. What a Homecoming!

We docked in the New York lower bay area, disembarked and were taken by Army vehicles south to Fort Dix, a US Army Base near Browns Mills, New Jersey. The third day after our arrival at Fort Dix, we were informed that all California people would be leaving the next day.

We boarded a C-47 Army Transport plane and within the hour were in flight. The flight took about nine hours – we reached Camp Beale, Marysville, northern California late afternoon on January 29, 1946.

My reunion with my family was a most joyful one. My service years left a deep emotional bond in my heart, and even today I feel like an extended family of those serving Our Country in the Armed Forces.

The authors would like to thank Dan Leary (ASN: 39232383), (X-Ray Technician) who initially collected the original text from which this Article is derived, in his collection of

203d General Hospital Testimonies entitled “203rd GH: An Anthology of Members.” We would also like to thank him and his family for their kind donation of some of

the images which appear in this Testimony.

The authors would also like to recommend the excellent website dedicated to the 203d GEN HOSP, which includes a detailed history and a plethora of images relating to the unit. It can be found here.