The Hospital Train in the E.T.O. 1944-1945

Demonstration illustrating a litter patient being helped into a Hospital Train ward car. Picture taken in England during the presentation and commissioning of a new Hospital Train in presence of local British and American military authorities.

Background and Introduction:

The idea of bringing medical attention to casualties through the medium of the Hospital Train was in fact an outgrowth of the “Ambulance Train” used during the First World War (21 Hospital Trains, purchased in England and France, were operated by the A.E.F. in the Great War –ed). During the interbellum years, the Medical Corps studied the Ambulance Trains of WW1 closely, with the result that in WW2, Hospital Trains became splendidly equipped modern hospitals moved via a train, where casualties in need of emergency treatment could receive immediate and expert care, while being evacuated to more ‘specialized’ medical units.

The first steps toward realizing the build-up of Hospital Trains in the United Kingdom was immediately confronted with difficulties. Although priority on labor didn’t seem to be a problem, the shortage of material in the British Isles to construct rolling stock was a real obstacle. It was furthermore impractical to ship equipment and materials from the Zone of Interior as every available shipping space was at a premium and other priorities existed. The only solution came with the suggestion from the British Railways, that old passenger cars and diners be converted into hospital cars. British rolling stock could thus be used with the wagons altered by the (British) Swindon Railway Works according to specs (modified to fit existing British cars) submitted by the US medical authorities.

Technical Requirements:

Lt. Colonel Sidney Bingham, Transportation Corps, Military Railways, was aware that maintenance was half of the story of any piece of equipment, and while Hospital Trains were in the process of construction at the Great Western Shops, he assigned 30 Enlisted Men and 1 Officer to study their building. Maintenance was one the principles of the project to be studied (ultimately it was decided to attach a maintenance crew to each Hospital Train –ed).

When completed, a Hospital Train would consist of 14 wagons, 7 of which were ward cars equipped to accommodate from 250 to 317 casualties, depending on whether they were litter, ambulatory, or mental cases. The pharmacy car was the most important component possessing a detailed O.R. with all the necessary equipment; the rest of the Hospital Train consisted of a kitchen car and sleeping quarters for the medical staff. Where British Hospital Trains were dependent upon the locomotive for heat, light, and other necessities, these trains each carried an independent power plant to keep them operational on railway sidings when the locomotive was detached for other uses.

The very first Hospital Train procured from the British on 24 March 1943 was mainly used for training purposes until such time that more Hospital Trains could be acquired for evacuation of patients within the United Kingdom. The FIRST Hospital Train obtained for use with the US Army Forces stationed in the British Isles was received on 2 June 1943 (by 1 September 1943, 15 Hospital Trains were operational in the United Kingdom –ed).

Interior view of a Hospital Train ward car illustrating the setup of the beds. The latter haven’t yet been made up and have no bed linen. Picture taken in the Zone of Interior, continental United States.

Because the distances between some Station and General Hospitals were so great (motor ambulances were not used for distances over 25 miles –ed), a Hospital Car was constructed by British Railways from plans drawn by Lt. Colonel Bingham. It had a capacity of 12 litter and 11 sitting patients, and each car was self-contained having adequate messing, heating, and toilet facilities. The cars were staffed by 1 Nurse and 3 EM from Hospital Train units, and were moved on regular scheduled runs of the passenger service in the U.K. The first of these hospital cars was put in operation on 17 September 1943, and by the end of December 1943, 5 such cars were in full use.

The United States Hospital Trains and Hospital Cars were under direct control of the Chief Surgeon, Services of Supply, and were operated in accordance with instructions and policies prescribed by the Chief Surgeon, while maintenance, operation, and repairs were the responsibility of the Chief of Transportation. The Commanding Officer of the Hospital Train OR Hospital Car was in control of all personnel and patients being transported and responsible for the administration of the unit, including the preparation of the necessary records, reports, and returns as well as for the professional care and messing of all the patients; for the internal cleanliness of the train or car; and for the presentation to the local Railway Transportation Offices of the necessary requests for repairs.

Exterior painting of the Hospital Train was to be olive drab, with the largest possible Geneva Convention symbol (Red Cross on white background) painted on the roof, and similar but smaller designs painted near the front, and another near the rear on each side of the cars. Interior paint was to be three-toned: ceiling in mist gray; walls to window sill level in dove gray; and remainder of walls and floor in dark gray.

Operations:

The introduction and development of the Hospital Train program in the British Isles was another important phase in the “chain of evacuation” which would become highly effective and well tried immediately after the liberation forces moved against Hitler’s “West Wall”. Although Hospital Trains were used considerably in evacuating patients arriving at Avonmouth from North Africa, and also used for transporting patients for evacuation to the Zone of Interior, one of its main purposes was the training of personnel for introduction of Hospital Trains on the continent after the planned Invasion of France.

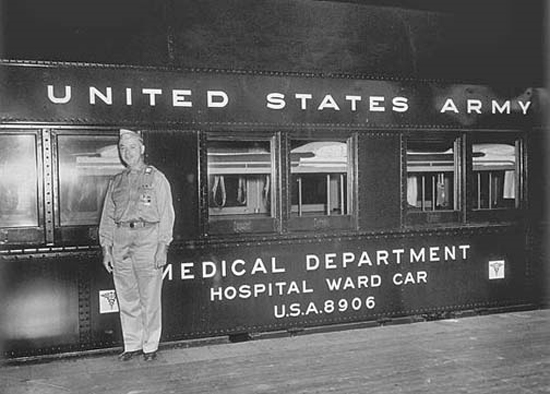

Outside view of a US Army Hospital Train at Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation, Virginia, waiting for patients to be directed to the various medical installations in the area.

Starting on D-Day (6 June 1944 –ed), casualties were evacuated from France by American naval craft, British Hospital Carriers, and brought to the southern shores of England, where they were moved by ambulance to transit Hospitals located not far from the shore. At the time, there were 11 transit Hospitals, each equipped to handle 1000 patients every 24 hours. By the end of this period, the patients, having been given the immediate medical attention needed, were shipped to a General Hospital, which could take care of their specific needs. The move from the transit Hospital to the General Hospital took place by Hospital Train. Besides the 15 Hospital Trains already running in the U.K., 10 additional overseas Hospital Trains were modified with Westinghouse air brakes, and were put in use for evacuating casualties from the transit installations.

Following D-Day, the Allied Forces drove across France at a pace which taxed every facility of the almost ruined transportation system. Railways and equipment had been badly damaged by the pre-Invasion bombing and were therefore in very limited supply. Roadbeds and bridges had to be repaired before trains could proceed at more than a snail’s pace. Approximately 48 hours (or more) were required for a train to run from Paris to Cherbourg, compared with a peacetime duration of 6 hours. By the time the Services of Supply had been established in Paris, it had already been evident that the number of Hospital Trains would be totally inadequate to meet the evacuation requirements.

In the period lasting from 6 June 1944 to 27 June 1944, there were 78 Hospital Train movements and 32 single Ambulance/Hospital Car movements in the United Kingdom which handled 22,925 patients. It was considered that some three hours were necessary to get a train in motion after a request had been received from the Chief Surgeon. Experiences on train movements indicated that a Hospital Train could be ready and in motion within two hours forty-five minutes after receipt of such request from the medical authorities.

Administrative Memorandum No. 93 relating to Hospital Trains operating in the United Kingdom, dated 17 June 1944 , was distributed by the Office of the Chief Surgeon, ETOUSA, APO 871.

The following Hospital Trains being used in the United Kingdom had following patient carrying capacities:

| BUNKS | LITTERS | AMBULATORY | PADDED | |

| Hospital Train No. 11 | 228 | 64 | 2 | |

| Hospital Train No. 12 | 228 | 64 | 2 | |

| Hospital Train No. 13 | 228 | 64 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 14 | 228 | 64 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 15 | 252 | 64 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 17 | 240 | 64 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 27 | 252 | 64 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 31 | 252 | 64 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 33 | 231 | 64 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 36 | 231 | 64 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 55 | 126 | 158 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 57 | 126 | 158 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 59 | 126 | 158 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 61 | 126 | 158 | 1 | |

| Hospital Train No. 64 | 126 | 158 | 1 |

US litters were to be used, if possible, for the evacuation of litter patients on Hospital Trains No. 17 – 27 – 31 – 33 – and 36.

The greatest care was to be utilized that Hospitals evacuate by Hospital Train ONLY those patients who can travel twelve (12) or more hours with reasonable safety.

Hospital Train in the field. Picture illustrating Hospital Train No. 77 at a standstill somewhere in France or Germany. European Theater of Operations, spring 1945.

The activities of the Hospital Trains on the continent (mainly France –ed) during the first months following the Invasion were slow to develop in comparison to the other means of evacuation because of the small area to which the fighting was limited. The main railway line running from Cherbourg to Bayeux was not reached by the Allied advance until 12 June 1944. On 26 June 1944, the railhead at Cherbourg (Cotentin Peninsula –ed) was captured and then there was almost a one-month period of waiting until the Armies remained static in the area of St-Lô. As early as 11 July 1944, the first scheduled American train run in France was made from Cherbourg to Carentan. By 25 July 1944, 90 miles of single and double lines were under Allied control, and by end of the month, 333 American train runs had been made and 31,907 tons of freight and 4,524 passengers had been moved. On 4 August 1944, the first Hospital Train (improvised from converted boxcars) arrived in Cherbourg. The slow pace of early operations of the Allied Armies prevented the quick transfer of the rolling Hospitals from Britain to the continent. Expecting such developments, the 2d Military Railway Service Company (which arrived in France on 17 June 1944 –ed) sent pre-fabricated sections for the conversion of boxcars into hospital cars to Normandy with the first rail equipment to cross the Channel. By 7 August 1944, 40 boxcars were fitted for temporary use as Hospital Cars. A 25-car converted Ambulance/Hospital Train which had been made over by personnel of a Railway Operating Battalion soon made its first run. 23 of the cars had been boxcars, while the other 2 were passenger coaches used by ambulatory patients. This train was almost exclusively used until 14 August 1944, when Hospital Train No. 27 was unloaded at Cherbourg. During the period from 1 August to 10 August 1944, this converted Hospital Train evacuated a total of 406 patients. On 30 August 1944, the first train entered Paris. By end of the month, the revitalized French rail system consisted of 750 miles of track (though with certain limitations –ed). Engineers rose to the emergency with track repairs and bridge replacements; Signal Corps linemen began to spin out their long lines of communication wire. Speed was emphasized and tracks were being laid so that the trains could get through, refinements would come later.

The use of Hospital Trains as a means of evacuating patients from combat areas to Hospitals in the Communication Zone and from General Hospitals in ComZ to the United Kingdom medical facilities increased in magnitude as the war progressed on the continent. This was due to the following reasons:

- lines of evacuation from the combat zone to Hospitals were lengthened considerably by the rapid advance of the United States Armies, and therefore motor ambulances could not be used exclusively.

- a more complete network of rail transportation was repaired and established.

- expected evacuation by air did not always materialize because of weather conditions, lack of coordination and agreement between Army and Army Air Forces, and a greater burden was therefore placed on the Hospital Trains.

By 18 September 1944, 3 Hospital Trains were operating in and out of Paris (Gare St.-Lazare –ed), and were doing a very big operation. These were soon to be reinforced by others forthcoming largely from the British and from the French. The Hospital Trains operated out of the Gare St.-Lazare (Paris) Station, and traveled between Paris and Lison, Chef-du-Pont, Charleroi, Reims, Verdun, Valognes, and Serfontaine. There were at this time no communications between the Military Railway Office in Paris and trains en route to Paris, so the Paris office had no idea of the number of patients or expected arrival of the train which caused many difficulties. A coordinated service of communication was established later, enabling constant contact between the Hospital Train, the local Railway Transportation Office, and the Office of the Chief Surgeon, so that all necessary arrangements could be made for meeting the train before its arrival. The Hospital to receive the patients was designated, and the means of transporting the casualties to the Hospital made available. Ambulatory patients usually rode in buses, while litter patients were taken in ambulances. The approximate time of travel for these trains to various points was from 24 hours to 72 hours.

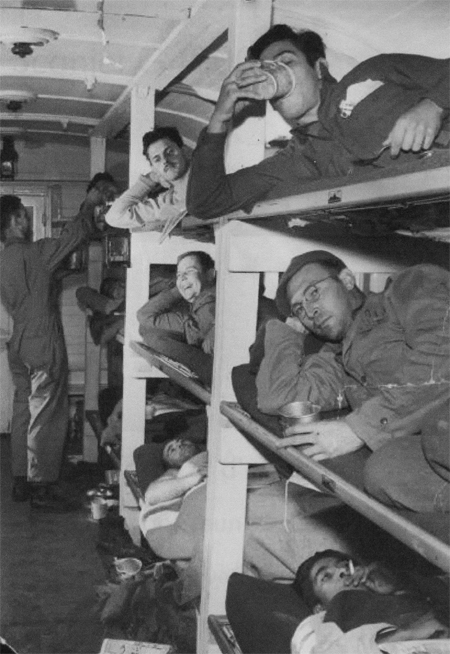

Internal view of a Hospital Train ambulatory car with sleepers. The car comprises three-tier berths on either side to accomodate 24 patients. Picture taken in the Zone of Interior, U.S.A.

Example of trips made on 18 September 1944 and numbers of patients carried:

| FROM | TO | LITTER CASES | AMBULATORY PATIENTS |

| Paris | Lison | 228 | 64 |

| Chef-du-Pont | Paris | 186 | 0 |

| Charleroi | Paris | 252 | 64 |

| Reims | Paris | 297 | 0 |

| Charleroi | Paris | 299 | 0 |

| Verdun | Paris | 252 | 64 |

For the weeks ending 9 September and 16 September 1944, 1600 and 1100 patients respectively were carried on the continent by Hospital Trains. With the extension of railroad lines further east to Liège, Belgium, on 15 September 1944, the US Army Transportation Corps began running Hospital Trains for the evacuation of wounded from within fifty miles of the frontline of the First United States Army. A Transportation Corps railway operating crew drove an Army Hospital Train into Belgium just two days after the first reconnaissance train crossed the Franco-Belgian border. Supplied with sufficient motive power to move the Hospital Trains to any point on the rail lines, the Military Railway Service (MRS) only required notice from the Office of the Chief Surgeon in need of a train at a certain point. To insure the continuous, faultless operation of the fleet of Army Hospital Trains on the continent, the Transportation Corps offered several special Hospital Train Maintenance Platoons and Sections. Units were stationed at receiving stations and depots to inspect the cars, all their running and mechanical parts, and repair them immediately if necessary (small mobile railway workshops were also available –ed). This was important as the loss of time due to mechanical failure would hamper operations and cause a backlog of casualties in combat areas.

To help alleviate the shortage of Hospital Trains, which on 25 November 1944, stood at 25 (70 were needed –ed), the Transportation Corps and the Medical Department considered every possible means to obtain added equipment, and to compensate for the shortage by improving the existing methods of operation. It was determined that by cutting the turn around time, there would be a greater availability of Hospital Trains. This was done in one instance by arrangements with Colonel L. B. Meachan, G-4, for obtaining priorities for Hospital Trains running from Normandy to Paris. Also Colonel F. H. Mowrey, MC, Chief of Evacuation Branch, Operations Division of the Office of the Chief Surgeon, attended a conference with Major General Paul R. Hawley, Chief Surgeon, ETOUSA, and Brigadier General J. H. Stratten, G-4, on priority for Hospital Trains running to Verdun, Liège, and Cherbourg. The running time from forward areas was improved. Toul > Paris, required nine to eleven hours; Liège > Paris eighteen to twenty hours; Paris > Cherbourg necessitated four to five days. Turn around time was cut by designating trains from various areas to operate out of particular railway stations. Lt. Colonel R. Gantz, MC, Seine Base Section, was informed (after coordinating with the Transportation Corps) that trains operating between Paris and Verdun, Toul and other points southeast would be operated from the Gare de l’Est (Paris). By effecting this change, the turn around time could henceforth be reduced four to six hours.

Construction of new Hospital Trains was expanded to the greatest extent possible. The French agreed to construct 9 Hospital Trains for delivery prior to 1 February 1945. The equipment furnished by the French Railways was adequate to meet the need and would be built to the specifications of the Office of the Chief Surgeon. An agreement was reached that the equipment of trains would follow the same procedure as used in building the British-type trains (the Medical Department would furnish all medical equipment and the Transportation Corps would deliver the trains complete with litter racks –ed). On 4 October 1944, 2 Hospital Trains were under construction from existing French rolling stock. In the mean time, construction in the United Kingdom of 2 improvised Hospital Trains for use by the United Kingdom Base Section was carried on, thereby releasing more units for shipment to the continent. From 10 August 1944 to 20 November 1944, Hospital Trains moved 73,835 patients on special train operations.

Air evacuation direct to Hospitals in the United Kingdom aided much to alleviate the shortage of Hospital Trains. The trains loaded for Normandy (with destination Cherbourg –ed) and evacuation across the Channel were as far as possible loaded with ambulatory patients with litter patients held for evacuation by air, unless the latter was deficient and evacuation by rail remained the only means available for getting litter cases out of Paris. This was implemented as much as possible, because patients evacuated to Cherbourg had to stand a train ride up to fifty hours before unloading. Although it was important to evacuate patients from the many Paris Hospitals as soon as possible to make room for incoming casualties, proper triage of the wounded for evacuation by rail and by air to the U.K. was highly important, and not under any condition were casualties to be evacuated when in a questionable state of transportability.

With the end of the conflict in Europe in sight, plans were made for the use of such French Hospital Trains as would be required in Germany for the Army of Occupation. However, the French “Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer Français” ( S.N.C.F.) demanded the return of its rolling stock. This required the building of 3 Hospital Trains and 3 separate Hospital Ward Cars from captured German rolling stock. During active operations, none of the available 47 Hospital Trains were considered wholly adequate.

Separate Notes:

British-built Hospital Trains:

Hospital Trains furnished from British sources were of two distinct types: the bunk type and the litter type, and consisted of 14 cars, half of which were ward cards. Both were constructed of similar equipment. All cars were of the uniformed un-reinforced wooden material in normal use by all major British Railways. Ward cars were built from baggage cars, personnel cars were obtained from slightly modified first class sleepers, ambulatory patient cars came unchanged from passenger wagons, as did the kitchen-diner cars. Without exception, these trains proved to be the most unsatisfactory of any Hospital Trains in use, even though the five bunk-type car was considerably better than the litter-type car. The primary objection was the lack of protection afforded the patients and personnel in case of accident. Another major factor was the lack of heating or ventilating systems for the patients’ cars (only source of heat was a double two-inch steam line –ed), the bunk-type cars did have a small fin-type radiator affording only minimal heat. Furthermore, there was no heating in the lavatories, no heating of the water pipes, and the ward cars had no windows since they were based on baggage cars. Sanitary facilities were primitive and privacy only consisted of a curtain. A chemical toilet was the only fixture (bedpans and urinals had to be emptied into it by hand –ed). The only source of hot water was a gasoline burner with a small overhead cold water tank. Lighting was insufficient and based on a storage-battery which had to be kept charged by the train axle-operated generator. Hard unadjustable bucket seats were most uncomfortable for the ambulatory patients, and the litter patients had extremely rough journeys lying on stretchers without any cushioning or padding (only the bunk-type cars had beds with springs –ed). Although demoded and really unsuitable, they were the only available means of conveyance at the time.

Partial view of the Gare St.-Lazare, Paris, France. The Seine Section, provided stabling and servicing for the entire ComZ Train complement (including troop and hospital trains) at the Gare St.-Lazare, which became the central hub for Hospital Train units in France. Headquarters, 343d Medical Battalion, were tasked with administration and operational control of Hospital Trains, Motor Ambulance Companies, Litter Detachments, and Air Holding Units, and became responsible for the overall evacuation management.

French-built Hospital Trains:

The most satisfactory Hospital Trains used in the E.T.O. were those built from French equipment. When compared to the British-type, the French Hospital Trains were more efficient and more modern, with some coaches already provided with double doors to permit easy loading and with provisions for anchoring litter brackets. The only technical drawback was the antique coal-fed boiler (soon replaced with British-built Clarkson boilers –ed). The first group was built hurriedly without time for thorough planning or fine workmanship. Experience in building however soon produced improvements to be incorporated into the next train. As more time became available to lay down complete plans, to procure materials, and to effect finer workmanship, the overall quality of the French-built Hospital Trains improved considerably.

The French-built Hospital Train was composed of 17 cars (later reduced to 15 for more efficient operation –ed) of all-steel construction, broken down as follows:

Car No. 1 – boiler car

Cars No. 2 & 3 – ambulatory car

Cars No. 4 to 7, and 9 to 12 – ward cars

Car No. 8 – surgery, pharmacy, office and ablution car

Car No. 13 – combined kitchen & storage or personnel car

Car No. 14 – standard railway diner car

Car No. 15 – Enlisted personnel car

Car No. 16 – Officer & NCO car

Car No. 17 – baggage car

Remark: Car No. 3 and Car No. 12 were later withdrawn.

American-built Hospital Train:

Only 1 American-built Hospital Train was available in the European Theater. This train was designed on pre-war drawings, and suffered from inadequacy to a Communications Zone ravished by strategic bombings and invading Armies. The Hospital Train conformed in general to the design of the usual European goods wagon or freight car, built out of wood and reinforced with steel for additional protection. It consisted of:

Car No. 1 – Officer personnel car

Car No. 2 – Enlisted personnel car

Car No. 3 – kitchen car

Cars No. 4 to 9 – ward cars (accommodating 16 patients each)

Technician Fourth Grade Glenn Wasem poses in front of a ward car of Hospital Train No. 23. Picture taken in France.

While being more comfortable and safe, the train was found to contain many unsatisfactory features. No dining room, little privacy, berths did not allow for gentle movement of patients, inefficient fluorescent lighting, defective generators, no alternate steam provision, limited patient capacity (only space for 100).

The all-steel construction was its most valuable feature, together with a more practical bed-pan washer and sterilizer available in the ward cars.

German-built Hospital Train:

The return of the French Hospital Trains necessitated the construction of Hospital Trains from German rolling stock. Based on experience and existing drawings and reports from current Hospital Trains, it was decided to build a train consisting of:

Car No. 1 – utility car (containing heating, laundry, workshop)

Car No. 2 – ambulatory car (accommodating 24 sleeping patients or 36 seated patients)

Cars No. 3 to 5 – ward cars (accommodating 30 litter patients each)

Car No. 6 – surgery car (including 4 compartments for office, operating room, pharmacy, and medical storage)

Cars No. 7 to 10 – ward cars

Car No. 11 – kitchen car

Car No. 12 – combination diner & lounge car

Car No. 13 – Enlisted personnel car (including 5 compartments for 2 men each, with storage compartment)

Car No. 14 – Enlisted personnel car (including 12 compartments for 2 men each)

Car No. 15 – Officer personnel car (including 12 compartments for 2 men each)

Car No. 16 – baggage & brake car (with compartment for brake crew and conductor)

General Conclusion:

It was concluded that the “ideal” Hospital Train could only be ideal insofar as it could be made from standard rolling stock rapidly converted to the specialized use of evacuation. The conduct of war involved the practical use of materiel, either specially manufactured and prepared for the purpose, or adapted to military use from existing civilian or captured equipment. The Hospital Train was a railway unit, locomotive, tender, and a number of cars, specially designed for the transportation of sick and wounded personnel. Based on actual experience during combat operations it was determined that a load of approximately 250 patients was the optimum which would permit proper professional attention and assure to the operating staff the minimum comfort necessary to maintain efficient morale and workmanship on a 15-car Hospital Train.

The ideal Hospital Train was therefore to consist of the following:

Car No. 1 – utility car

Car No. 2 – ambulatory car

Cars No. 3 to 5 – ward cars

Car No. 6 – surgery & office car

Cars No. 7 to 10 – ward car

Car No. 11 – kitchen car

Car No. 12 – diner & lounge car

Car No. 13 – personnel & baggage car

Car No. 14 – Enlisted personnel car

Car No. 15 – Officer personnel car

The above short Article was based on some vintage documents supplied by Lynn F. McNulty (one of our main sources of original medical-related Unit Histories) to whom we will always remain grateful for his valued assistance. The original historical documents were prepared by Tec 3 Lewis N. Furda (10 December 1944) and by Lt. Colonel John W. Koletty (14 October 1947). Some of the illustrations used are courtesy of Robert Batman and Ellen Willits-Smith.