Class 9 Items: Drugs, Chemicals and Biological Stains Blood Plasma & Equipment Miscellaneous Medical Equipment

Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944. Soldiers of the 16th Infantry Regiment (1st Inf Div), being treated for injuries, and wounded soldier receiving plasma.

Background:

The use of blood transfusion as a treatment for shock was first introduced by the British Third Army troops during World War One. Members of the casualty Clearing Stations realized that hemorrhage was the single most important factor in causing casualty shock, and so plans and measures were made which allowed the most crude of Aid Posts to administer whole blood transfusions to casualties.

Major W. Richard Ohler, who had served as a resuscitation officer during WW1 claimed that the amount of hemorrhage suffered determined the amount of shock suffered by a patient, and as a result the need for oxygen-carrying corpuscles, and no other form of saline solution, as had previously been thought. Despite the efforts of the British Third Army during WW1 and the claims by men such as Maj. Ohler, it was not until March 1918 that the US Army Medical Department officially adopted transfusion with citrated blood as the method for combating shock and hemorrhage in hospitals of the American Expeditionary Force.

By 1939, both the Allies and Axis forces had seen the benefits of whole blood transfusion during the Spanish Civil War, in which over 9,000 liters of whole blood were collected and administered to casualties with the most severe symptoms of shock. A critical breakthrough was also made during the war, in that it was discovered that initial treatment of shock should include both whole blood and blood plasma, as opposed to earlier thought whole blood and serum.

The “Blood for Britain” program, introduced during the 1940 had enjoyed limited success with whole blood, and in August of 1940, the American Red Cross began to collect blood from donors in New York City for export of plasma to Britain.

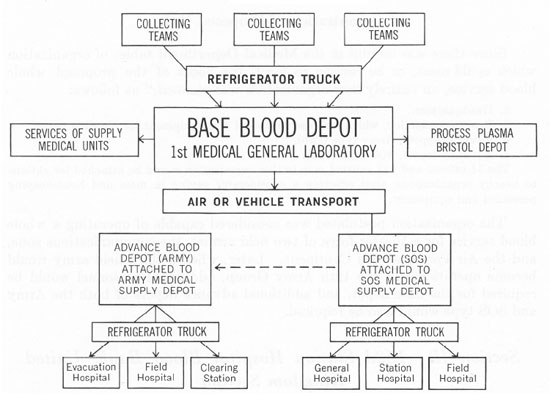

Operations Chart showing the Whole Blood Service in the ETO during 1943.

U.S. Army surgeons in the E.T.O. learned from British experience in the Western Desert, and from early American operations in North Africa and Sicily, that whole blood, while highly perishable and difficult to store and transport, was indispensable for controlling shock in severely wounded soldiers. Blood, administered as far forward as possible in the front lines and in the evacuation chain, saved many lives that plasma alone could not! The American “Blood Bank” program took shape during late 1943 and early 1944, and since no blood bank existed, everything had to be improvised!

The 152d Station Hospital (250-bed capacity) was reorganized into a Base Depot, which was to collect O-type blood (the only kind used) from volunteer Services of Supply (SOS) donors, process it, and prepare it for daily shipment to France, where the Advance Medical Depots, using truck-mounted refrigerators, would distribute it to the Field Hospital Platoons attached to Division Clearing Stations. The necessary equipment for the units came from the United States, under a special “Project for Continental Operations”(PROCO), and from the British, who furnished indispensable refrigeration units, bottles, tubing and needles for bleeding and transfusion. By mid-1944, the Blood Bank, under overall control of the 1st Medical General Laboratory (Salisbury), and with Major Robert C. Hardin, MC, in charge, had secured most of its equipment and finished organizing and training the necessary 11 Officers and 143 Enlisted Men of its Base, ComZ, and Army Depots. Agreements for priority shipments of blood to France, were negotiated with both E.T.O. authorities and with the Ninth Air Force.

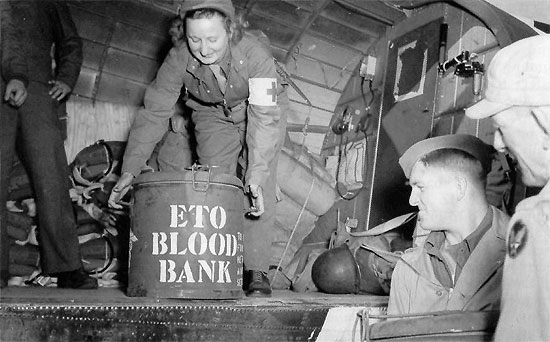

Whole Blood was packed in ice in insulated marmite cans, originally designed as QMC food containers, for further air transportation across the Channel to the continent. These cans were then loaded onto refrigerator trucks which delivered the blood to advance units with the Armies in the field.

Late in May 1944 (eve of D-Day), the Theater Blood Bank began collecting and processing, and its detachments started their first deliveries, i.e. over 1,100 pints to LSTs and British Hospital Carriers, fitting out at English, Scottish, and Welsh ports taking on blood and biologicals for their own use and for supply to the Beachheads the day of the Invasion …

The advent of Dried Plasma:

Stock room for liquid plasma at the Army Medical School. The liquid plasma was stored at room temperature here, and supplied to hospitals in the Zone of Interior.

The supply of whole blood plasma, either as frozen or liquid plasma proved to have limited success, but the need for the correct storage conditions meant that its use in the front line often meant access to refrigeration units, which in many cases were not available. As a result, large biological and pharmaceutical laboratories began to process whole blood into dried plasma. This new technology meant that plasma could be transported and stored by front line medical functions, and administered as and when needed.

Evolution:

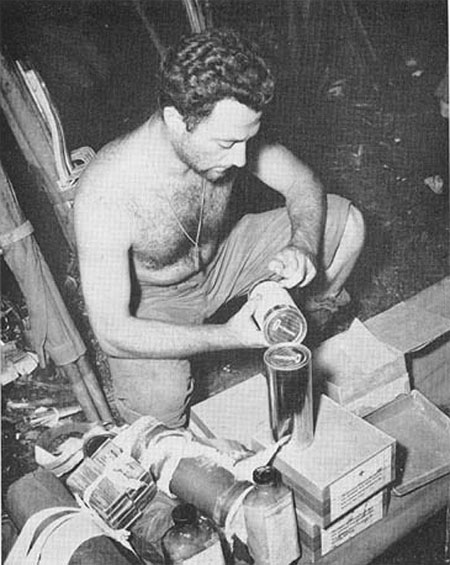

Preparation of plasma for administration to casualties. 43d Infantry Division Hospital, Rendova Island, Solomon Islands, July 1943. The use of Item No. 1608900 is clearly visible here.

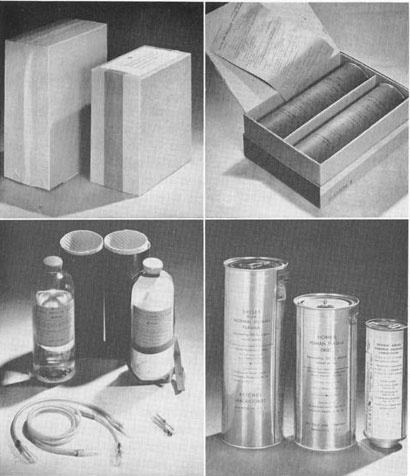

The first 15,000 units of dried plasma were produced by Sharp & Dohme. These units consisted of two glass vials, one containing distilled water and the other, dried plasma. In addition an intravenous needle and rubber tubing were also supplied in the loosely packaged carton. While this equipment did represent the best method of frontline administration and reconstitution, the shape of the vials meant that an impractically large package was needed to supply the equipment to medical personnel in the front line. These original packages could yield a total of 220 cc. of plasma, although this was often less stable because a process of double-processing was required. In addition to their glass vials, both the distilled water and dried (desiccated) plasma were supplied in tin cans, although the packaging was so loose that breakage was considered inevitable. Despite these shortcomings, 25,000 units were ordered, but unsurprisingly, they did not stand up to use.

In a meeting held on 19th April, 1941, Dr. Strumia developed a new form of package which was suitable for both dried and frozen plasma, and consisted of the following:

- A 400-cc. bottle of distilled water, of hard, non-corrosive glass, with square shoulders.

- A similar bottle containing 250 cc. of dried plasma, with residual moisture of less than 1%

- A gum-rubber vaccine type of stopper, about three-fourths of an inch in diameter, containing a glass airway. After a vacuum had been drawn on the plasma bottle, the stopper was covered with a heavy gel cap.

- An intravenous set for administration of the reconstituted plasma.

Unlike the earlier glass vials, the bottles in this new package would be placed in tin cans filled with nitrogen, and then sealed under vacuum. It was anticipated by Strumia that with slight modification the package would be acceptable for front line Army use.

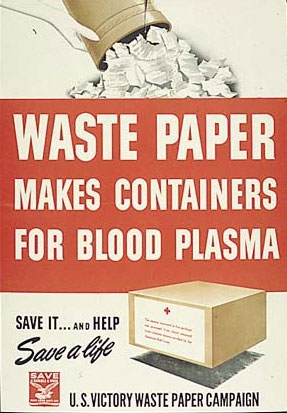

Waste Paper Drives were held in the US in an effort to recycle paper which was in turn used to produce the plasma packaging.

During the 18 July 1941 meeting of the Subcommittee on Blood Substitutes, the equipment and packaging developed by Commander Newhouser and Captain Kendrick, which were slight modifications of the Strumia packaging, were recommended for Army use and with only minor modifications, the packaging was used by the Army throughout the war.

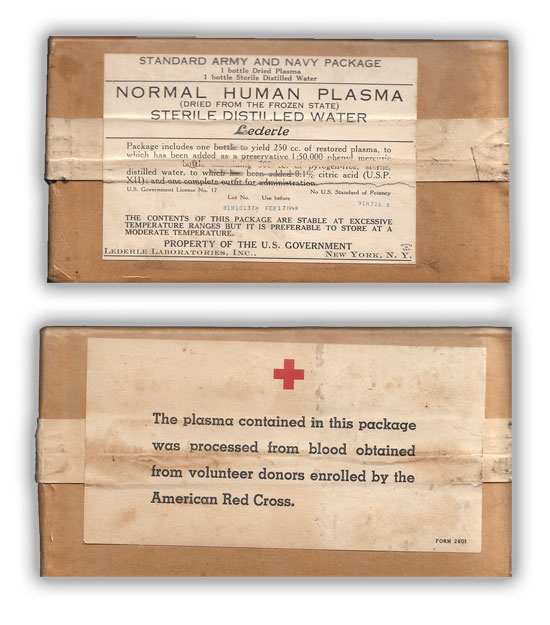

Front and rear pictures of the early Standard Army-Navy Package (Item No. 1608900). This package was manufactured by Lederle Laboratories Inc., New York, N.Y.

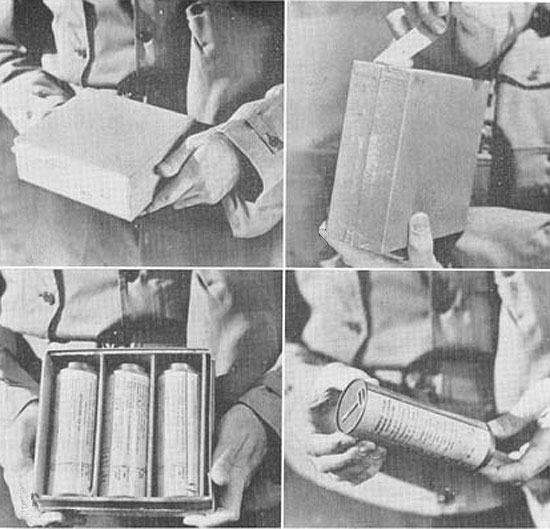

The resultant Standard Army-Navy Package (Item No. 1608900) consisted of the following:

- A 400-cc. bottle containing the dried solids obtained from 300 cc. of citrated plasma, evacuated and sealed under 29 inches (73.6 cm.) of vacuum. The solid content contained between 17.5 and 18 gm. of plasma protein. An earlier proposal (1) that the labels on plasma containers should specify the amount of the original plasma from which the dried plasma had been prepared would have required individual determinations of total protein and was rejected as completely impractical.

- A 400-cc. bottle, with a similar stopper but sealed without a vacuum, containing 300 cc. of sterile, pyrogen-free distilled water.

- Equipment for intravenous administration, consisting of:

- An airway assembly, consisting of 9 inches of rubber tubing, with a needle on one end for insertion into the stopper and a cotton filter on the other end.

- An intravenous injection set, consisting of 48 inches of rubber tubing with a glass cloth filter for use during the administration of the plasma. At one end of the tubing was a glass adapter fitted to an 18-gage intravenous needle. At the other end was a short 15-gage needle to be used to connect the intravenous set to the plasma bottle. This was Item No. 9351520.

Once the distilled water had been mixed with the desiccated plasma, within 3 minutes the plasma was ready for administration and was healthy for use for a further 4/5 hours.

Testing the Package:

The new standard package had undergone testing under combat conditions during Pearl Harbor in 1941. However, in the meantime it had also undergone the following tests, as recorded in Lt. Col. Douglas B. Kendrick’s Memorandum Report of December 1942:

- Six packages were placed in a refrigerator variously, right side up, upside down, and on their sides at -4° F. (-20° C.) for 18 hours. When the packages were removed from the refrigerator, all could be opened easily. The water was solidly frozen, but thawed satisfactorily at room temperature, in hot tap water, and in a water bath at 98.6° F. (37° C.), without breakage.

- Eight packages were placed in a Dry-Ice refrigerator car at -148° F. (-100° C.) for 18 hours, four on their ends and four on their sides. When they were removed, the tape bindings were frozen, but the boxes were easily opened at the end of an hour. Thawing of the distilled water was accomplished by the methods just described, with equal ease and no breakage.

- Packages forwarded to the Fleet Surgeon, U.S. Pacific Fleet, were sent out with landing parties and placed under 5-inch (12.7-cm.) and 12-inch (30.5-cm.) guns during firing practice and during dive bombing in the months of May and August 1941. The cans were somewhat battered, but they had retained full vacuum and there was no breakage.

The larger Plasma package:

Comparative shot showing the larger plasma package, used to yield 500 cc. of Plasma, compared to the earlier less effective 250 cc. The smaller container shown in the bottom right portion of the image is Serum Albumin.

As early as 1941, it had been realized that if a casualty needed plasma, 250 cc. (as supplied by the current Army-Navy Package) was insufficient. As a result the Army began developing larger packages which would yield more plasma, but maintain the practicability of the package. Experimental work had shown that by the use of a 750-cc. bottle, 600 cc. of plasma could be dried to a residual moisture of less than 1 percent. By the use of a 9½-inch can instead of the 7-inch can presently in use, 500 cc. of plasma could be packaged in a box only 2 inches longer than the box presently in use. Eighteen large packages would occupy the same space as 24 small packages but would represent the same quantity of plasma as 36 small packages.

Production of this larger package did not begin until July of 1943, and the delay had been caused because it was feared that the change in tooling and dies necessary to produce the larger package would be a difficult process. In spite of this, the changeover was finally made and the larger packages began to find their way overseas. Production of the smaller, 250 cc. package was continued by Parke, Davis & Co., and Ben Venue Laboratories until the end of the war.

The Development of Serum Albumin:

Illustration showing the packaging of Serum Albumin. Three tins, each containing 100 cc. of Serum Albumin, were contained in the package, which was preferable for Navy use as the package floated, unlike its heavier, plasma counterpart.

Towards the end of the war, dried plasma began to be replaced by Serum Albumin, the most abundant plasma protein in human blood. The serum was preferable as it was a standard US Navy item used for the priming of explosives, and thus no delay was necessary in its procurement, unlike the dried human plasma.

The development and introduction of this new item meant that another package had to be designed. Once again Commander Newhouser and Colonel Kendrick came up with a solution, as described below:

- 100 cc. of 25-percent normal human serum albumin prepared from human plasma.

- One double-ended glass vial, with a rubber stopper at each end.

- One bale (suspension tape) for use with the ampule.

- One air filter assembly consisting of a three-fourths inch, 16-gage hose hub needle; 1 inch of rubber tubing to fit the hose hub needle; and cotton to be placed in the rubber tubing to serve as an air filter.

- One injection assembly, consisting of 40 inches of rubber tubing; one three-fourths inch, 16-gage hose hub needle; one plastic test tube and stopper to protect the needle; one glass observation tube with ground glass Luer-type tip, 2.5 cm. in length and 2-3 mm. in diameter; one three-fourths inch, 20-gage intravenous needle, with plastic test tube for its protection.

- One metal can (three to a package) for each unit of albumin. The key to open the can was spot-welded to the bottom of the can, as in the plasma package.

The versatility and compact nature of the serum package meant that by the Korean War (1950), it had totally replaced dried plasma as the main treatment for shock by front line troops.

Conclusion:

The development of the Blood program in World War 2 was a real landmark, and the increased use of Whole Blood as well as Plasma was fundamental to medical success in saving the lives of wounded men!

By the end of the Second World War, the American Red Cross had collected and processed over 6,000,000 standard Army-Navy Plasma Packages. While many of these packages were used during the latter part of the war, especially during “Operation Overlord”, surplus packages were shipped back to the Zone of Interior for use in Army Hospitals and for use by civilians.