107th Evacuation Hospital Unit History

Cover of the booklet “The Story of the 107th Evacuation Hospital (SM)”. This publication was prepared by Captain Joseph J. Mihalich (Detachment Commander) and Tehnician 5th Grade Martin Chancey (Office of Information & Education), who served with the 107th EH during World War Two. Its subtitle is “Five Stars to Victory”.

Introduction & Activation:

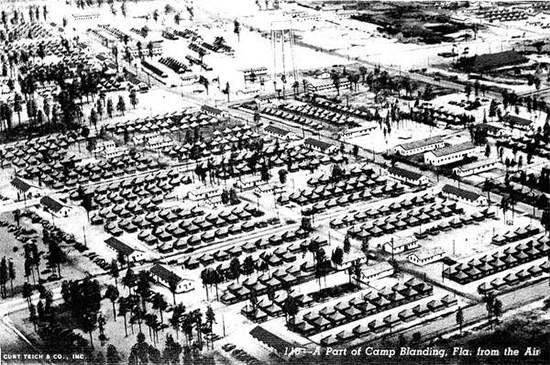

The 107th Evacuation Hospital was officially designated a Semimobile (SM) unit by Army Ground Forces Letter, File 321.113 (Med) (R) GNGCT, dated 28 March 1943. The 107th Evacuation Hospital (Semimobile) was activated on 20 May 1943 at Camp Blanding, Starke, Florida (Infantry Replacement Training Center; acreage 152,672; troop capacity 2,157 Officers and 58,570 Enlisted Men –ed), as per Headquarters, Second United States Army, Letter, Order A-246, dated 6 May 1943, with Lt. Colonel Henry W. Daine, MC, O-17804 in command (formerly Division Surgeon, 2d Infantry Division).

To assist the new CO with his administrative task, the following group of Officers was assigned:

Major Leslie P. Herd, MC

Major Alexander H. Howell, MC

Captain David C. Hazard, DC

First Lieutenant Oscar Bergman, DC

First Lieutenant Louis R. Davanzo, MAC

First Lieutenant Harrison Gray, MAC

First Lieutenant Joseph. J. Mihalich, MAC

Second Lieutenant Albert J. Costine, MAC

Second Lieutenant Paul W. Mocko, MAC

Second Lieutenant Frederick W. Mozart, MAC

Second Lieutenant Prentice C. Woodhouse, MAC

Chaplain George W. Zins

Aerial view of Camp Blanding, Starke, Florida, where the 107th Evacuation Hospital was activated 20 May 1943.

Shortly afterwards, an Enlisted cadre of 34 men, furnished mainly by the 21st Evacuation Hospital (activated 17 August 1942, embarked for Guadalcanal, 29 August 1943 –ed) then at the Desert Training Center, in California, arrived and preparations were made for a Training Program. The date was to be 11 June 1943. On that particular day a train arrived from Fort Devens, Ayer, Massachusetts (Military Reservation; acreage 11,796; troop capacity 2,066 Officers and 33,232 Enlisted Men –ed), with a precious load of 182 sky-happy men, all known as filler replacements, and with this group, the 107th Evac would commence its training program and the hospital, as a unit, began to take form.

It wasn’t easy for these youngsters to conceal their keen disappointment that fate had brought them to a medical unit thus dashing their hopes for a glorious career in the Air Corps!

Ten (10) days later the new organization welcomed Lt. Colonel Howard S. Reid, MC, who as the Chief of the Medical Service, was to play a distinguished part in the life of the unit.

Organization:

The organization was based on T/O & E 8-581, dated 8 January 1943 and intended for use as a 400-bed semi-mobile unit normally attached to a Field Army. The term (SM) reflected the organization’s capability to move its equipment by organic transportation and personnel by shuttling. The hospital’s initial strength between 2 July 1942 and 25 March 1944, would evolve from 39 Commissioned Officers, 1 Warrant Officer, 48 Nurses, and 248 Enlisted Men to 38 Officers, 1 Warrant Officer, 40 Nurses, and 217 EM, an aggregate of 296.

Picture illustrating vintage Camp Gordon, Augusta, Georgia, Pennant

Timeline:

Timeline – 107th Evacuation Hospital

20 May 1943 > Unit is activated at Camp Blanding, Starke, Florida

11 June 1943 > Filler replacements arrive from Fort Devens, Ayer, Massachusetts

27 September 1943 > Unit moves to Camp Gordon, Augusta, Georgia

30 October 1943 > Unit is alerted for participation in No. 8 Second United States Army Maneuvers

9 November 1943 > Unit leaves Camp Gordon, Augusta, Georgia

11 November 1943 > Unit arrives at Shelbyville, Tennessee

14 November 1943 > First complement of 20 Nurses arrives

18 November 1943 > Unit moves into Tennessee Maneuver area

18 November 1943 – 7 January 1944 > Tennessee Winter Maneuvers

19 November 1943 > Unit stays at Castilian Springs, Tennessee

2 December 1943 > Unit stays at Baxter, Tennessee

10 December 1943 > Unit stays at Murfreesboro, Tennessee

16 December 1943 > Unit stays at Shelbyville, Tennessee, and sets up winter quarters

22 December 1943 > Unit stays at Cookeville, Tennessee, Hospital setup with one Echelon

2 January 1944 > Unit is alerted for Overseas Movement

19 January 1944 > Unit moves to Camp Tyson, Paris, Tennessee, Staging Area

15 February 1944 > Unit leaves Camp Tyson, Paris, Tennessee

18 February 1944 > Unit arrives at Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey, Staging Area

27 February 1944 > Unit sails from New York POE on AP-72 “Susan B. Anthony”

9 March 1944 > Unit reaches Belfast, Northern Ireland

11 May 1944 > Unit moves from Belfast, Northern Ireland, to Denbigh, North Wales on AP-182 “George W. Goethals”

7 July 1944 > Unit moves to Marshalling Area, Southampton, England

11 July 1944 > Unit crosses English Channel on S/S “Victoria”

12 July 1944 > Unit arrives at Omaha Beach, Normandy, France

12 July 1944 > Unit bivouacks in Transient Area # 3 near St.-Laurent-sur-Mer, Normandy, France

13 July 1944 > Unit personnel splits into 4 groups for DS with 2d, 5th , 24th and 44th Evacuation Hospitals in Normandy, France

16 July 1944 > Unit personnel reassembles and sets up Hospital at Le Défant, near St.-Sauveur-le-Vicomte, France

2 August 1944 > Unit moves to Bréhal, Brittany, France

10 August 1944 > Unit moves across Brittany on its way to Ploudaniel, Brittany, France

11 August 1944 > Unit opens Hospital at Ploudaniel, Brittany, France

13 September 1944 > Unit opens Hospital at Châteaulin, Brittany, France

27 September 1944 > Unit starts big move across France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and sets up bivouac in vicinity of Rennes, Brittany, France

28 September 1944 > Unit bivouacks near Chartres, France

29 September 1944 > Unit bivouacks in vicinity of Suippes, France

1 October 1944 > Unit opens Hospital at Clervaux, Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg

27 November 1944 > Unit closes for admission of patients, only Dispensary continues operation

16 December 1944 > Unit receives warning orders for possible movement to undisclosed destination

17 December 1944 > Battle of the Bulge starts, German breakthrough takes place in the Belgian Ardennes, Unit moves to Château de Roumont, Libin, Belgium

21 December 1944 > Unit receives orders for evacuation, Unit moves to Institut St. Joseph, Carlsbourg, Belgium

22 December 1944 > Unit receives orders to move immediately to Sedan, France, personnel is billeted at the Collège Turenne and the Hospital established at l’Ecole du Textile, Sedan, France

1 January 1945 > Unit is bombed and strafed by enemy aircraft while set up at Collège Turenne, Sedan, France

21 January 1945 > Unit moves to Pensionnat St. Joseph, Hachy, Belgium

1 March 1945 > Unit moves on to Diekirch, Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg

16 March 1945 > Unit moves on German soil for the first time, and opens Hospital in German Orphanage at Mayen, Germany

7 April 1945 > Unit crosses the Rhine River

8 April 1945 > Unit effects stop-over at Kassel-Rothwesten, bivouacks at Fliegerhorst Rothwesten, Germany

13 April 1945 > Unit reaches Thamsbrück, Germany, moves once more into tents

26 April 1945 > Unit bivouacks outside Weiden, Germany

30 April 1945 > Unit opens Hospital outside Regensburg, Germany

21 May 1945 > Unit arrives at Würzburg, Germany, 300-bed Hospital set up in buildings of former German Reservelazarett, functions like a Station Hospital

10 July 1945 > Unit designated Category IV for Redeployment

1 August 1945 > Unit operates as Station Hospital at Würzburg, Germany

8 September 1945 > Unit is replaced by 124th Evacuation Hospital at Würzburg, Germany

(CO > Colonel Don S. Wenger)

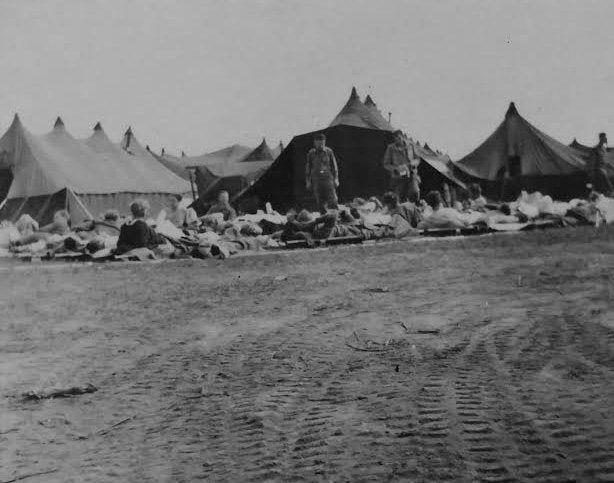

Partial view of 107th Evacuation Hospital bivouac. Photo of tentage probably taken somewhere in the field during the No. 8 Tennessee Maneuvers.

Training:

The thirteen-week Basic Training Program which painstakingly tried making disciplined and skilled medical soldiers out of a motley crowd of filler replacements was now under way.

But even in those early days the men had their first taste of pride in the performance of their organization. On the third day of basic training, the Officers and Enlisted Men of the 107th participated in a parade reviewed by Lt. General Lloyd R. Fredendall, CG, Second United States Army. It was their first concerted effort as a unit and they were resolved to give it their best. Comments from observers were most favorable, even when compared to units much more advanced in their training. The days and weeks were rapidly rolling, with the personnel continuing with daily routine calisthenics, close order drill, and numerous classroom lectures ranging from military courtesy to anatomy and physiology.

In the middle of August 1943, Major Kenneth D. Grace, MC, shortly to be appointed Head of the Surgical Section, arrived and was greatly impressed by the level of training, as he watched the men apply leg splints, treat simulated shock, and improvise means for transportation of patients.

Upon completion of the last six weeks of general Basic Training the unit was ready to initiate ‘specialized’ training of selected groups. Without such specialists an Evacuation Hospital could not give the definitive treatment in combat. Then, during the weeks that followed, groups of selected men were dispatched to various General Hospitals for intensive training as Surgical, Medical, and X-Ray Technicians. It was early September when the motor convoy of the 107th reached the “Twin Lakes” area for three days to establish and operate the first hospital with simulated casualties for patients. When a week later, another bivouac was held, the hospital was quickly set up and proceeding to function efficiently. Aerial photographs of this bivouac site revealed that not only was tentage pitched in an excellent manner but that the whole installation was expertly camouflaged.

Portrait of Colonel Henry W. Daine, MC, O-17804, Commanding Officer, 107th Evacuation Hospital (SM). Photo taken while the organization was set up in Würzburg, Germany, May – September 1945.

The completion of Basic Training in the middle of September 1943 was marked by the arrival of a team of Inspectors from Second US Army. Following a number of tests, the unit received a ‘satisfactory’ rating.

Following Basic Training, and while trying hard to reach authorized T/O strength with many fillers and additional personnel coming in, the new hospital received instructions on 27 September 1943 to move to Camp Gordon, Augusta, Georgia (Division Camp; acreage 55,708; troop capacity 2,171 Officers and 43,055 Enlisted Men –ed). On 30 October 1943, the organization was alerted for participation to the No. 8 and No. 9 Second United States Army Maneuvers planned in Tennessee (this was considered as a final stage of advanced training). After packing the complete hospital with equipment and personnel left by motor convoy departing Camp Gordon early on 9 November 1943.

The plans contemplated setting up a complete medical installation in the wilds of Tennessee and practise with real patients pertaining to the various US Army Divisions on training prior to movement overseas.

A first contingent of 13 ANC Officers arriving from Fort George G. Meade, Baltimore, Maryland (Army Ground Forces Replacement Center; acreage 18,048; troop capacity 2,019 Officers and 35,131 Enlisted Men –ed), and following transfer to Camp Forrest, Tullahoma, Tennessee (Infantry Division Camp; acreage 73,124; troop capacity 1,886 Officers and 32,368 Enlisted Men –ed), they were joined by another 7 Nurses. The whole group was subsequently assigned to the 107th Evacuation Hospital arriving at the unit’s bivouac at Shelbyville, Tennessee, on 14 November 1943.

Picture illustrating four Nurses of the 107th Evacuation Hospital. Taken in the Zone of Interior, the ANC Officers are still wearing the SSI of the Second United States Army. Time for chow?

In the period between 18 November 1943 and 7 January 1944, the 107th Evac functioned, continuously moving and changing location sites almost once a week. Sites such as Shelbyville, Castilian Springs, Beech Grove, Cookeville, Baxter, Murfreesboro, were some of the places ‘visited’ by the unit. The hospital worked hard, changing sides, alternating medical support to the “Blue” and “Red” Forces and learning field technique. A total of 2,783 patients were cared for during above period.

Together with the arrival of 14 additional Medical Officers and the hospital equipment came the news that the Commanding Officer was promoted to the rank of Colonel.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

Following the end of the Tennessee Maneuvers, the 107th returned for a short break at Shelbyville (approximately 16 miles from Camp Forrest –ed) where the tented camp was winterized. While personnel lived in tents, the hospital proper functioned in two large garages. The weather turned for the worse bringing more sick cases due to the cold, the damp and rainy weather, including some patients victims of road accidents and a few personnel suffering from VD. It was learned that improvisation in the field resulting from either loss or non-availability of certain equipment items was essential.

For winter quarters the entire personnel was housed in pyramidal tents, while the equipment and supplies and two wards were set up in two garages. New Year found the unit reunited. The 107th Evac had successfully met its first great test and had gone through 2 months of field operations and problems while supporting the 35th – 87th – 100th Infantry – and 11th Armored Divisions. It had ministered to many hundreds of patients under adverse natural conditions. The valuable experience gathered and the lessons learned during this maneuver period were in the large part responsible for the ability of the 107th to cope with the great ordeal of the Christmas and New Year of 1944-45, and to come through with flying colors! At the conclusion of the Tennessee Maneuvers, the hospital was given a rating of ‘satisfactory’.

Picture illustrating Officers of the 107th Evacuation Hospital standing around their CO, Colonel H. W. Daine. Most probably taken around the end of the war in Würzburg, Germany.

On 2 January 1944, the 107th Evacuation Hospital was alerted for movement overseas. On 19 January the unit moved to Camp Tyson, Paris, Tennessee (Barrage Balloon Training Center; acreage 7,014; troop capacity 772 Officers and 12,543 Enlisted Men –ed), where it was to stay for 4 weeks. The 20 Nurses who assisted the unit during the Tennessee Maneuvers were now officially attached and joined their parent unit at Camp Tyson later in January. The remainder of the ANC Officers also arrived to complete the T/O. Meanwhile training continued however much the personnel wanted to relax and enjoy the luxuries of garrison life again.

On 15 February 1944, the 107th left Camp Tyson entraining for its Staging Area, Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey (Staging Area for New York Port of Embarkation; acreage 1,815; troop capacity 2,074 Officers and 35,386 Enlisted Men –ed), where it arrived three days later. Training was never forgotten with more close order drill, marches, callisthenics, gas warfare measures, abandon ship drill, and more. After due processing, a last briefing, followed by some recommendations and lectures on military censorship, and final 12-hour passes and leaves, the 107th Evacuation Hospital was ready for war! Departure by truck, followed by train, and ferry to reach the pier started during the night of 26 February. ARC volunteers were on standby at the pier ready with hot coffee and donuts. The organization finally sailed from New York P/E on the USS “Susan B. Anthony”, AP-72 (ex-ocean liner built in 1930, and converted to a US Navy troopship in 1942 –ed) on 27 February 1944.

United Kingdom:

The 107th Evac was not the only unit on board. Medical personnel from the 32d Evacuation Hospital, the 42d Field Hospital, and the 103d Evacuation Hospital were also traveling aboard the “Susan B. Anthony”. Quarters on and below deck were more than crowded. Life on board was spent playing cards, reading, often interrupted by work in sick bay, on KP detail, and daily observance of security and blackout conditions. Some men watched the convoy’s progress, while others felt miserable and seasick.

The Atlantic crossing proceeded uneventful except for some rough seas during the trip upsetting many a stomach.

Picture illustrating a group of ANC Officers of the 107th Evacuation Hospital. Also taken at the end of the war in Germany and most probably during the organization’s stay in Würzburg.

Land was finally sighted 8 March, and on 9 March 1944 the “Susan B. Anthony” reached the shores of Northern Ireland, debarking at the Port of Belfast.

A welcome committee of British Officers came on board and after a short meeting with their American counterparts, escorted staff and personnel down the gangplank, from where they were taken to a line of waiting 2 ½-ton trucks. The trucks soon reached a residential area of Belfast, named Knockdene Park, were the Officers, the Nurses and the Enlisted Men were to be billeted in vacated private homes. At the beginning the food was poor, the quarters cold, but gradually this all improved, though slowly. By 15 March 1944, training once more began with early morning calisthenics, followed by lectures and classes, and drill, plus road marches in the afternoon.

Recreation was no problem with Belfast only a 10-minute ride away by bus. Soon an Officers’ Club was set up and on Sundays sightseeing trips were organized in the area. Moreover living in a civilian community made life much more pleasant as quite a few of the locals invited the men and women of the 107th to their private homes for tea and conversation. A well-organized sports program had always proved the main source of the unit’s recreation and once more softball games between Officers and Non-coms were the center of this program. More difficult was coping with the capricious weather and the art of building fires with that fire-resistant Irish coal.

Picture illustrating Troop transport “Susan B. Anthony”, AP-72. The ship left New York Port of Embarkation on 27 February 1944 carrying the 107th Evacuation Hospital across the Antlantic to Northen Ireland, where she arrived 9 March 1944. Photo taken 23 April 1943.

9 May brought some changes. The 107th Evac was alerted for a change of station and moved back to the Port of Belfast in order to travel to North Wales. By early dawn of 10 May 1944, Headquarters staff and personnel, following a quick breakfast of coffee and donuts entrucked for the docks where they boarded USAT “George W. Goethals” AP-182 (launched 23 January 1942 and delivered to the US Army in September 1942 –ed). The trip was short with the “Goethals” docking at Avonmouth (near Bristol), England, around 2300 hours the same day. At 0100, 11 May, after more donuts and coffee everyone boarded a civilian train.

The group arrived in Denbigh, North Wales mid-afternoon of the same day. The advance party was waiting at the railway station. After a quick welcome, the 107th personnel were told that they were going to live with private families (in fact the whole of Denbigh was turned into a camp area), in total 120 homes were used for billets. After a short march, along narrow up-hill streets to the field where the mess hall was situated, a hot meal was waiting. The mess hall itself consisted of a single large hutment established in a field, where formations could be ideally held. Food was good and an innovation was music while having meals which everyone seemed to enjoy.

Recreation however was almost non-existent within the area. After several weeks an abandoned church was cleaned and set up as an Officers’ Club, with dances being held there. Movies were shown in the mess hall. Cycling became a favorite pastime for most, as many purchased local bikes. Twenty miles away was Rhyl, the only fair-sized town to visit which offered concerts or movies, and some socializing. French and current war event classes were started at this time. Calisthenics, drill, and organized athletics continued to be held at the beginning of each day followed by lectures and films. The last week of May 1944, 4 ANC Officers went on DS to the 64th and 83d General Hospitals near Wrexham, Wales, to review and update their OR technique and skills. The following week another 20 Nurses were sent to the Army Field School near Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England.

It was during May that the personnel actually began setting up the hospital in the field. The Nurses were assigned to their respective wards, and classes were held for Nurses and Enlisted Men alike on new procedures, while also practising at the same time. Since part of the necessary equipment had not arrived, ANC Officers combed Denbigh for glass jars and tin containers. During one field problem, the whole hospital was moved into an adjoining field and set up anew. Most of the time was spent in preparing and making OR equipment. Sheets, wrappers, bandages and white lining for the Operating Rooms had to be prepared. It was during their stay in North Wales, that the personnel were issued more field gear and combat clothing. Meanwhile last minute preparations, including packing and crating of equipment for a sea voyage continued, while staff and personnel were lectured on passive air defense and recognition of enemy aircraft. With the arrival of 2 American Red Cross representatives, a plan was instituted for providing welfare facilities and rounding out the program of activities.

Picture illustrating one of the piers of the Omaha Beach Artificial Harbor taken some time around mid June 1944. The personnel of the 107th Evacuation Hospital landed at Omaha Beach, Normandy, France, on 12 July 1944.

With several Officers and EM taking part in D-Day operations, the Invasion took on a more intimate meaning.

After being alerted for overseas movement, the organization prepared its move from Denbigh to the planned Marshalling Area, at Southampton, England. On 7 July 1944, the 107th Evac left Denbigh, North Wales, by train for Southampton, where it arrived the next morning. The next three days were spent at the camp, well hidden in the dense, soggy woods, in getting last minute instructions and equipment. Free time was spent with movies. It rained continuously.

France:

11 July 1944, it was time to go, so, clad in fatigues, dressed in impregnated clothing, loaded with individual gear and packs, the 107th Evac Hosp departed England for the continent. Channel crossing would take place aboard a British transport, the SS “Victoria”. The Nurses went into the hold with the other Officers; the EM were set up everywhere else. The voyage itself was uneventful, except conditions which were appalling. The ship proved poorly ventilated, men and women were packed like animals, the sea was rough with many sick notwithstanding anti-seasickness pills, and food (not many felt hunger) was distributed in the form of 10-in-1 rations.

Fortunately the sea voyage was short and around noon 12 July 1944, the French coast was in sight. It was a beautiful and sunny day. After being transferred to the smaller LCTs, everyone moved on to one of the piers, part of the Omaha Beach artificial (Mulberry –ed) harbor complex. The Enlisted Men walked to the assembly area, while the Nurses entrucked for Transient Area #3 at St.-Laurent-sur-Mer. At first everything looked very unwarlike, except for the steady roar of patroling aircraft and C-47s cargo planes evacuating patients to the United Kingdom and the endless stream of troops and supplies coming ashore. Individual pup tents were pitched for the first time on the continent. It was here that the organization was to spend its first night making the acquaintance of “Bedcheck Charlie” which came over nightly to bomb, strafe, and harass the troops.

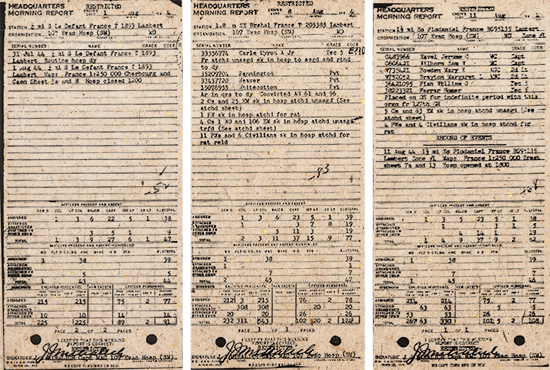

Set of copies of 107th Evacuation Hospital daily Headquarters Morning Reports, respectively dated 1 August 1944 (Le Défant bivouac), 8 August 1944 (Bréhal bivouac), and 11 August 1944 (Ploudaniel bivouac).

The next morning, because the organizational equipment and transportation had not yet arrived, the Commanding Officer, following consultation with higher authoritiy (FUSA Command) directed that personnel be divided into four equal groups, each group to go on DS to the 2d, 5th, 24th, and 44th Evacuation Hospitals. These temporary assignments provided invaluable experience. With the severe fighting going on for St-Lô, patient census was constantly on the increase.

It should be underlined that the initial number of Evacuation Hospitals set up for First United States Army during the planning phase of the Normandy Invasion, was for an Army composed of three Corps. With its build-up on the continent, the medical services were augmented during the period of 26 June to 1 August 1944, by the following Evacuation Hospitals of the Third United States Army (which was to become fully operational on 1 August 1944 –ed):

32d Evacuation Hospital

34th Evacuation Hospital

35th Evacuation Hospital

39th Evacuation Hospital

100th Evacuation Hospital

102d Evacuation Hospital

104th Evacuation Hospital

106th Evacuation Hospital

107th Evacuation Hospital

109th Evacuation Hospital

All of these units reverted to TUSA control on 1 August 1944 with the exception of the 106th and 109th Evacuation Hospitals, which were returned at a later date. ADSEC (Advance Section, Communications Zone –ed) made the 77th Evacuation Hospital (affiliated to the University of Kansas, activated 10 May 1942, embarked for England 5 August 1942 –ed) available for use on 21 July along with 3 Motor Ambulance Companies which were given the task of evacuating patients from the Evacuation Hospitals to the beach (at the height of the D-Day operations for the period lasting from 6 June to 31 July 1944 inclusive, 22 Evacuation and 6 Field Hospitals were assigned and attached to FUSA for medical support of 16 active combat Divisions –ed).

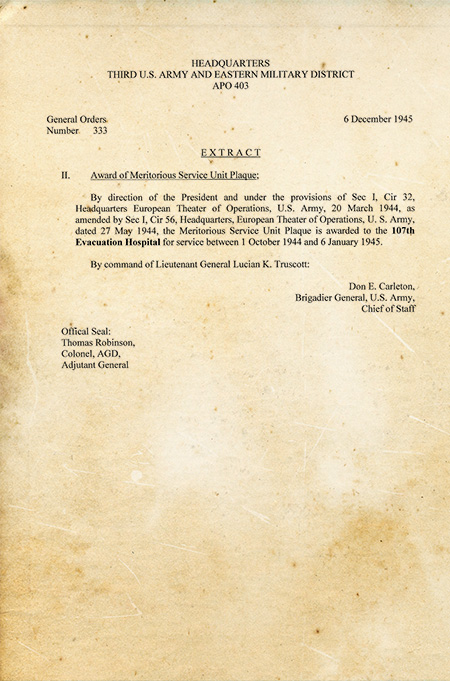

Partial view of bivouac of the 107th Evacuation Hospital following the capture of Brest, Brittany. A large number of German wounded PWs are grouped in front of the organization’s tentage awaiting triage and admission. Photo taken some time around mid-September 1944.

Normandy

On 14 July word was received that the unit’s equipment had landed. Two days later, 16 July 1944, the hospital assembled at the site of the 44th Evacuation Hospital and subsequently proceeded by motor convoy to a bivouac area outside of St.-Sauveur-le-Vicomte (the new site called Le Défant was situated ½ mile south of St.-Sauveur-le-Vicomte –ed). The drive to the area gave everyone a first true glimpse of the ravage caused by war. Debris was found everywhere, with rubble, abandoned equipment, destroyed vehicles, along the way. Traveling in dust and heat the convoy passed through towns such as Isigny and Carentan continuing westward across the Cotentin Peninsula to St.-Sauveur-le-Vicomte. It was late that evening when the motor convoy finally arrived at its site. The personnel slept in ward tents and was ready to start working the next day. Roster and duties were established and excitement grew while the Enlisted personnel pitched additional tents for receiving patients. It was surprising to all how quickly the hospital went up. That same night, being readied for incoming patients, the 107th Evac opened. Surgery was set up in two ward tents with three tables in each. While getting ready for functioning, standard procedures were still being developed, as this was the organization first setup in a war zone. Consequently many details had to be ironed out by the trial and error method before everything worked out. The main problem encountered concerned blood. Since “Blood Banks” were not fully in effect at the time it was therefore necessary to look for donors within the command. Starting 31 July 1944, work began for real! A 12-hour shift was adopted and the necessary breaks included with breakfast from 0730 to 0830 hours, lunch from 1300 to 1400 hours, and dinner from 1930 to 2030 hours. In its first two weeks of operation, the hospital admitted 807 patients. The 107th Evac initially opened as a unit assigned to FUSA, but a mere few weeks later it was transferred to General G. S. Patton’s TUSA which was gathering men and armor for its breakthrough at Saint-Lô.

Overall living and working conditions were satisfactory, the weather was good, the sun shone, and the canvas tents were relatively comfortable. The humidity, dampness and occasional rains did cause problems as mildew set in as equipment and clothing were continually moist or wet. Nights were cold, and stoves did not always function properly. One of the methods to protect from the cold was to wear clothing in layers and in order to try and keep clothes dry for the next morning, they were kept inside or under the sleeping bags. With the weather steadily improving, it was warmer during the day, bees started coming in droves, attracted by sewage and any food left without attendance. Spiders, occasional moles, and birds found their way around the hospital site and made life better during off-duty hours. The food gradually improved to include C-rations and fresh white bread. It also became possible to acquire more local produce from some farmers in the neighborhood.

Medical personnel of the 107th Evacuation Hospital and 3/4-ton Dodge ambulance in the background.

It was during this time that the 107th acquired its first enemy PWs to help with the work. Most of them were fairly young and not all were ethnic Germans, but included a few Poles and Russians who had been forced to join the German Army following the defeat of their countries in 1939 and 1941.

The 107th Evacuation Hospital closed 1 August 1944, after having treated 850 patients.

The second part of the westward trip across the Cotentin Peninsula took the trucks of the 107th through La-Haye-du-Puits, Lessay, and Coutances, to Bréhal (in fact 1.8 mile southeast of Bréhal, situated almost halfway between Coutances and Avranches –ed), the unit’s second station in France. Traces of the war never seemed far away; abandoned equipment, a cow blown up by a landmine, and hastily-dug individual German graves. The motor convoy arrived late at night and while Officers and Enlisted Men quickly pitched some tents, the Nurses slept in the ambulances. Setting up in pouring rain, the hospital was ready for patients by 1500 hours, 3 August 1944. Nearly 1,400 patients were handled at the new station. It was here that a Third United States Army ammo dump was bombed about 5 miles away from the hospital site. Although there was much excitement over the incident, work continued as usual. Within 15 minutes a truck loaded with mutilated bodies of a colored ordnance crew were brought in for emergency treatment.

A first batch of 300 patients was received and within one week 700 wounded were admitted to the hospital.

Picture illustrating a group of Non-coms of the 107th Evacuation Hospital. Taken during fall of 1944, in the European Theater, either in Luxembourg or in Belgium.

The 107th Evacuation Hospital travel route from its landing at Omaha Beach across the Cotentin Peninsula towards Brittany went as follows: after the unit’s debarkation at Omaha Beach 12 July 1944, followed by some rest, DS with other medical units, and arrival of its organizational equipment, the hospital made its way to Isigny, Carentan, St.-Sauveur-le-Vicomte, La-Haye-du-Puits, Lessay, Coutances, Bréhal, Avranches, reaching Pontorson, Dinan, Landerneau, Ploudaniel, Châteaulin, finally returning to Rennes in Brittany, before crossing France in an eastward direction.

Stations & Bivouacs in France – 107th Evacuation Hospital

Bivouac, Omaha Beach – 12 July 1944 > 13 July 1944

Detached Service with other Hospital units – 13 July 1944 > 15 July 1944

Operating Hospital, St.-Sauveur-le-Vicomte – 16 July 1944 > 31 July 1944

Bivouac, Bréhal – 3 August 1944 > 9 August 1944

Operating Hospital, Ploudaniel – 11 August 1944 > 9 September 1944

Operating Hospital, Châteaulin – 13 September 1944 > 26 September 1944

Bivouac, Rennes – 27 September 1944

Brittany

The 107th closed its operation near Bréhal at 2230 hours, 9 August 1944. On 10 August 1944, the hospital moved by motor convoy over 150 miles, departing Bréhal, continuing through Avranches and Dinan via Pontorson and some smaller towns. Destroyed buildings and war debris were to be seen everywhere. The convoy drove on passing through Landerneau where it received a warm welcome, with cheering crowds in the streets, waving French and Allied flags, making “V” signs, throwing flowers, and offering wine to their liberators. Having moved across a great part of Brittany, Ploudaniel was finally reached around 2200 hours with the unit setting up somewhere in an open field in the town’s vicinity. The hospital was set up in an open field some 1½ mile south of Ploudaniel, and was ready to receive patients at 1800 hours, 11 August 1944.

Picture illustrating the main Operating Room, 107th Evacuation Hospital, while established at Clervaux, Luxembourg, October-November 1944.

While work was the same, everyone had to work harder because of the influx of casualties. Routine was often interrupted by the daily bombings during the siege of Brest. Fighting was harsh, with the patient census constantly on the rise. It even became difficult to work during night because of the fires, the smoke, and the noise of battle. A large group of wounded enemy was received 20 August 1944. A major transfer of patients took place on 31 August. The organization’s code name during its operations in the ETO was “Heathen”.

While stationed near Ploudaniel, Brittany, the unit treated 2,458 patients. The hospital closed on 9 September 1944, ready for yet another permanent change of station.

On 13 September 1944 the 107th moved to a new site near Châteaulin on the Crozon Peninsula. Twenty (20) enemy PWs were once more assigned to help with menial tasks at the hospital site.

The Crozon Peninsula had been fortified to help defend Brest. The final US attack began on 15 September 1944. The personnel were not very busy at their new site, although the fighting remained severe and 1,557 patients were received, the bulk of which were German casualties brought in “en masse” from a German hospital, following the fall of Brest. With Brest liberated 17 September 1944, there was due cause for a celebration and, for the first time since the 107th Evac landed on the continent, they were entertained with a dance organized by the 2d Infantry Division. As soon as the fighting stopped, culminating with the surrender of the city, the 107th Evac was tasked with grouping all American casualties for treatment and evacuation. Personnel did try to procure the same kind of care and treatment to Germans as they did for Americans (nearly 36,000 Germans were captured and over 2,000 enemy wounded evacuated and treated –ed). This became difficult when large numbers of enemy wounded were brought in, but the hospital staff and personnel did everything they could to care for all patients, including the wounded French civilians.

Being the first Evacuation Hospital to arrive in the Brest area, the unit supported nearly all American units participating in this campaign. Among the largest units were listed; the 2d – 8th – 29th – and 83d Infantry Divisions, as well as the 6th Armored Division. It was a short and hectic campaign with 1,557 admissions for the period.

Following the end of this operation, the 107th was relieved and assigned to Ninth United States Army (code name “Conquer”).

Across France

Towards the end of September 1944, the 107th Evacuation Hospital departed from Brittany. On 27 September 1944, the motor convoy began its long trip with final destination Belgium and Luxembourg. After striking all tents, packing and loading, and a quick meal, the convoy, consisting of 69 vehicles, among which 8 ambulances, began its 700-mile trip across the center of France. After a 150-mile stretch there was a first bivouac near Rennes, Brittany, where the advance party had set up some tents and constructed a latrine. The next phase of the voyage was “special” and for many the great moment had arrived, which all personnel so fervently looked forward to: catch a glimpse of Paris, the Capital City of France. However, it was night time, and all one could see were the big somber, still blacked-out buildings and monuments, with few people walking in the streets. A short stop on the outskirts of the city, then it was back in the trucks, and Paris was behind the convoy. During this hop, the biggest in the unit’s history, the Hospital traveled from 1600 until 0200 hours, so as to free the highway in daytime for the “Red Ball Express”.

After another 12-hour drive a stop-over followed at Chartres on 28 September. Apparently, nobody had fully realized the distance that was to be covered. Traveling would mostly take place later during daytime with arrivals planned around midnight and bivouacs established on the outskirts of large towns (three had been foreseen during which simple K-rations occasionally supplemented by locally-purchased tomatoes, onions, and eggs, served as meals).

At the last bivouac, near Suippes, France, which was reached 29 September 1944, a formation was called. The CO, Lt. Colonel Howard S. Reid, MC, addressed the men and women, “Your job as Liberators is now over. Pretty soon, you will be coming as Conquerors, surrounded by a hostile population. From now on I want you to watch your step, and to be especially careful. May I again express my hope that none of you will be separated from your dog tags.”

The convoy then started on its last lap. It was the fourth night on the road and it rained steadily as during the previous nights. Draped as they were in wool blankets over ODs and fatigues, the men shivered as the cold wind whipped through the canvas of the trucks and the never-ending drizzle “ate” into their very bones. The convoy now drove past some of the old WW1 battlefields, the final resting place for so many Allied soldiers who took part in the Great War. For endless miles there was not a single farmhouse to be seen in this zone. All too frequently, there was row upon row of white crosses on either side of the road. Many thought about the cratered, shell-pocked earth, the trenches and underground tunnels where thousands of men fought and died so that the First World War might be the last.

Vintage pictures illustrating the 107th Evacuation Hospital while set up in Luxembourg and Belgium, prior to the outbreak of the German counter offensive (Battle of the Bulge) in Belgium, 16 December 1944. Picture illustrating one of the ANC Officers in front of the organization’s tentage.

Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg:

Soon the blacked-out convoy, still driving in the rain, began passing the freshly-liberated Belgian towns and Luxembourg towns and villages. While the greetings were not as hysterical as in Brittany, there were still plenty of people on hand to shout, “Vive Nos Libérateurs” – “Thank you Americans” – “Long Live Liberty”. In the towns of the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, the most common slogans were; “We want to Remain what We are” and “Long live President Roosevelt and Grand Duchess Charlotte” (Grand Duchess Charlotte I, 1896-1985, was in exile in England and later in Canada, and only returned to Luxembourg 15 April 1945 –ed).

In the early morning hours of 30 September 1944, the 107th Evacuation Hospital convoy reached its final destination: a wind-swept hill (12 miles northeast of Bastogne, Belgium) near the city of Clervaux, Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg.

The hospital had to be set up and ready for patients by 0800 hours, 1 October 1944. The groggy, bleary-eyed crews, drawing upon their last bits of energy, plunged into the job with a real determination. The tent city was ready, established on a high hill near a planted pine forest overlooking the wide expanses of the Luxembourg countryside. Enlisted Men were ordered to pitch their individual pup tents inside the forest.

The rains came down, day in and day out, and within less than a week the mud became so deep and the roads so impassible that Engineers had to be called upon to build a gravel road. After weeks of mud (knee-deep in some places), the weather turned bitterly cold. Even the water in the Lyster bags and the water trailers froze, and the first snow made its appearance.

Having failed to outflank the Siegfried Line with the airborne operation launched against targets in Holland, on 17 September 1944, the nature of the fighting now changed to one of applying steady Allied pressure all along the fortified Ruhr and Hürtgen Forest, known to the doughboys as the “death factory”. The Germans were selling space for time and were determined to exact the greatest possible price. With the severe fighting came a steady flow of battle casualties, with a large proportion of patients sick with respiratory diseases and a growing number of trenchfoot cases. Many of these admissions were from the hospital personnel. The ceaseless drop of rain through the tall pines; the life spent in the cold and damp tents; the mud, first ankle-deep, then knee-deep. Mud everywhere, on the clothes, on the blankets, even in the food. All this proved a bit more rugged than many a constitution could endure. Again the Engineers came to the rescue and started erecting buildings from pre-fabricated German barracks. By the middle of November 1944, Receiving, Registrar, X-Ray, Surgery and part of the Ward section moved into wooden barracks. Unfortunately, Enlisted personnel remained in their tents or lived in one of the many primitive log cabins that sprang up in the pine woods.

More and more unit personnel were being admitted into the hospital. Days moved by slowly. Thanksgiving arrived, but everyone continued to gripe and beef as they ate their turkey and trimmings. Washing and shaving was done with icy water, Lyster bags still froze during the night, fires were difficult to maintain, foxholes and trenches were filled with water, and people went sleeping dripping with mud. And yet morale remained surprisingly high. The men knew too well that they had to be thankful for not staying among the doughboys who came into the hospital, their bodies mutilated by terrible tree bursts, screaming meemies, and other enemy fire. They were mighty thankful for not being in the shoes of the men who came in with swollen and black feet after standing hours in water-filled foxholes and not removing shoes and socks for two and three weeks.

Roentgenology constituted a perennial bottleneck when casualties were coming in rapidly and Surgical Technicians taxed their ingenuity to the limit to expedite the taking and development of pictures. The 107th Evac Hosp therefore sent patients in shock to X-Ray before resuscitation, in the belief that a slight delay in starting the latter process would be less harmful to the patient than a subsequent interruption of it. Using such expedients, the hospital was able to process masses of casualties. The method allowed to examine, sort, and place under shelter more than one (1) wounded man each minute.

In order to remedy shortages and deficiencies in resources, some units set up courses, with instructors drawn from their own units, to develop additional skills and techniques in order to remedy personnel scarcity. The 107th in order to take some of the burden from its one fully qualified Orthopedic Surgeon, trained its general surgeons in basic procedures for treating compound fractures and organized two teams of Enlisted Men skilled in applying plaster casts.

Between 27 November 1944 and 17 December 1944, the 107th waited for a new site to be assigned. However it never came. Some of the Nurses set about organizing a choir for the coming Christmas, and soon a group of Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men formed and started practising Christmas carols.

Station & Bivouac in Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg – 107th Evacuation Hospital

Operating Hospital, Clervaux – 1 October 1944 > 27 November 1944

Towards the end of November, “Bedcheck Charlie” became a frequent visitor. But this time something new had been added. With this regular visitor came the “Buzz-Bombs”. On certain days they kept coming over every 20 or 30 minutes, and at such times there was a prayer in everyone’s heart that they shouldn’t stop sputtering and start their descent. Many did come down only a few miles away. About this period all patients were evacuated. Personnel moved into the German barracks and life became a bit more comfortable. During their stay at Clervaux, the Nurses welcomed a new Chief Nurse: Captain Elizabeth H. Hay, ANC.

Belgium:

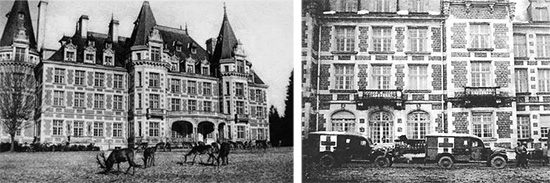

Picture illustrating Château de Roumont, Libin, Belgium, where the 107th Evacuation Hospital remained between 17 and 21 December 1944, following the German thrust in the Belgian Ardennes.

On 11 December new orders came through announcing a change of station. An advance party was dispatched to Aachen, Germany, to look for a new site. When they returned with a negative report it was decided on 16 December to unload all supplies and equipment and return the trucks borrowed for this anticipated move. The unit would stay in Luxembourg. The Special Service Officer reassembled his chorus of Officers, Nurses, and EM and resumed practice of Christmas carols. With resignation, the men concluded that the organization would probably be stuck in this mud hole till the next spring. To which people in the know added the hospital could afford to do so quite safely even though there very few American troops in the sector. The enemy couldn’t possibly attack through the impassible Ardennes forests that lay between them and the unit. Medical and Surgical teams were organized and 7 Officers, 2 Nurses, and a number of Enlisted personnel sent on DS to other organizations such as the 44th Evacuation and the 67th Evacuation Hospitals at Malmédy, Belgium (on 17 December 1944, subject units were compelled to withdraw from Malmédy and head for Spa –ed). To somewhat break the monotony of waiting, three passes to Paris were obtained for the Nurses and a dance organized by a nearby-stationed Engineer unit for Saturday, 16 December (cancelled because the building had been wrecked by enemy artillery fire –ed).

At 2230, 16 December 1944, warning orders were received for a possible movement. The Transportation Officer was immediately sent to First Army to draw 30 trucks. Things began to happen fast.

Battle of the Bulge

After the outbreak of the German counter-offensive in the Belgian Ardennes (16 December 1944 –ed), the 107th Evacuation Hospital, situated behind VIII Corps lines, managed to cease operations at Clervaux, Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, and was preparing to move. Brigadier General John A. Rogers (Surgeon > First United States Army), located at Spa, Belgium, after receiving the news of the German breakthrough early in the morning of 16 December ordered the withdrawal of some of his most exposed units in the rear of VIII Corps (this Army Corps controlled the 102d, 107th, and 110th Evac Hosp –ed). The 42d Field Hospital (First Platoon, Wiltz, Luxembourg) and the 107th Evacuation Hospital (Clervaux, Luxembourg) were instructed to withdraw to Belgium.

Stations & Bivouacs in Belgium – 107th Evacuation Hospital

Operating Hospital, Château de Roumont, Libin – 17 December 1944 > 21 December 1944

Partially Operating Hospital, Institut St. Joseph, Carlsbourg – 21 December 1944 > 22 December 1944

Station & Bivouac in France – 107th Evacuation Hospital

Operating Hospital, Ecole du Textile, Sedan – 22 December 1944 > 15 January 1945

Station & Bivouac in Belgium – 107th Evacuation Hospital

Operating Hospital, Pensionnat St. Joseph, Hachy – 21 January 1945 > 1 March 1945

The next day, it was barely 0500, the morning of 17 December 1944, personnel were awakened by the First Sergeant who shouted very excitedly: “Get the hell out of bed, throw your cots on the trucks, grab some chow and be ready to move at a moment’s notice!”

The shelling had become very intense by now, the sky was lit up with flashes of artillery fire, searchlights, and ack-ack. Soon reports started coming in about street fighting in Clervaux. Stragglers were now streaming in with horrible tales, some had escaped across the Our River followed by the Germans. Next came the almost unbearable hours of all; hours of waiting for transportation to arrive (not enough trucks available); waiting while shells crashed all around; with danger of being engulfed by the Nazi tide. At last, after five hours of waiting, the trucks arrived and the 107th departed around noon. Staying behind was an 18-man detail to take care of the equipment. Their stay was however cut short when a lone tank rolled up and one of the crew shouted from his turret; “This is probably the last friendly vehicle. The Krauts are right on my tail. You fellows better clear out!”

The 107th lost miscellaneous Class I, III, and IV items, but no major medical equipment. The majority of the tentage and quartermaster equipment was however lost.

Three members of the 107th Evacuation Hospital fooling around with a sign wishing everyone a “Merry Christmas”. Probably taken while the organization was billeted at the Collège Turenne, Sedan, France, from 22 December 1944 until 21 January 1945.

The 107th Evac, which had been closed (with all patients evacuated) when the enemy offensive started, worked while retreating; it first fell back from Clervaux, then to Libin (Château de Roumont 2 miles southeast of Libin), Belgium, where it admitted over 780 patients in eighty-two hours. After arriving at the Château’s palatial Hunting Lodge, a large five-story building, the litter bearers had to haul the patients up the four flights as there was no elevator. Some assistance was given by personnel belonging to the 580th Motor Ambulance Company also on site and by 2000 hours the hospital was in operation. Day and night everyone labored hauling and placing the many patients into the wards and to the ORs set up in the rose-and-pearl gray Banquet Hall. The building’s capacity was only 250 patients, and it was soon crowded with over 450 wounded. The latter were pouring in from different units and all sectors of the ruptured front and confusion was great. Commanding Officers came into the hospital looking for members of their units, and lonely Enlisted Men came searching for their Officers. During that period, one Platoon of the 42d Field Hospital arrived at the site minus all their equipment. The other Platoon had been surrounded at Wiltz, in Luxembourg. As ever more units were being overrun by the enemy, and more stragglers appeared in the 107th chow line. Reports came in of rampant Nazis ravaging and killing whoever they ran into. Being the only Evacuation Hospital so far forward in the combat zone, the sole concern of the dog-tired medical staff was to face their additional responsibilities in as calm and courageous a manner as did the doughs on the line; 388 operations were performed in an 80-hour period. There were large numbers of abdominal, chest, maxillo-facial, brain, and serious extremity cases to be treated, as most patients came directly from Battalion Aid Stations, since the normal chain of medical evacuation was greatly disrupted by the chaotic situation.

At times it seemed that the unit would crack under the terrible strain but the enormous pressure, fear, and tension only welded the personnel together even more firmly, single in its purpose and spirit. Men worked 12 hours at their usual assignment and then continued working as litter bearers for hours more. Even Officers carried litters. No one slept if they could in some way. The spirit was magnificent.

Major William E. Barfield (CO > 326th Airborne Medical Company) after contacting the Commanding Officer of the 64th Medical Group (assigned to TUSA, effective 21 December 1944 –ed), arranged for the evacuation of the wounded from the 101st Airborne Division Clearing Station to the 107th Evacuation Hospital (attached to 64th Med Gp, in support of VIII Corps –ed) at Libin, Belgium (Château de Roumont, situated between Ochamps and Libin –ed), and at the same time secured added ambulance support from that organization (in the form of jeep-ambulances –ed). At 1630, 19 December, the CO formed a convoy of 5 ambulance loads of patients, the first evacuation from the Division Clearing Station and led the way to the 107th Evac installations. On the return trip from Libin, the bridge located near Sprimont was found to be blown. Because of this, the dense fog and the fluid conditions of the enemy lines, Major W. Barfield returned with the convoy to the 107th where he remained overnight.

Meanwhile news arrived that the 101st Airborne had been surrounded at Bastogne and that the town had fallen. On 21 December, just when it appeared as if the organization was beginning to emerge from this chaos, a message arrived that enemy patrols were observed a few miles down the road heading for the hospital site. It was no longer impossible to ignore the fact that at any moment a bunch of Germans might walk into the front door. Orders came in: “Clear out in ten minutes!”- “Everything, yes everything but what you can carry on your back must be left behind.”. All patients that could be moved were speedily loaded on to ambulances and trucks, volunteers were needed to care for those that could not be moved. The 107th then evacuated 300 (out of their 400) patients on 21 December with the assistance from a Platoon pertaining to the 92d Medical Gas Treatment Battalion. All contacts with FUSA were severed and it was rumored that for ten days the hospital was listed as missing.

At least the consoling thought was that everyone would be away from mortal danger, then came orders for volunteers to get back inside the lion’s den to salvage any possible equipment. Before long, 5 Officers and 50 Enlisted Men had boarded trucks and were heading back to Château de Roumont amid the flash of guns and the roar of a revitalized Luftwaffe. Upon arrival, the volunteers witnessed the grim testimony of the timely get away of the unit. A German bomb had caved in part of the roof. From Libin, the route went further to Carlsbourg, where the unit partially set up in the Institut St. Joseph again the same day. The next day, 22 December, the hospital retreated for a final move to Sedan, France, where it found shelter in a former vocational school (Ecole du Textile occupied by FFI forces), while personnel were quartered at the Collège Turenne. The nearby bridge, continuously bombed and strafed by German planes caused patients to often dive under their beds. This situation was particularly hard on men suffering from battle fatigue, and there were many such among the 1,200 patients that were brought into the hospital after the siege of Bastogne was lifted. When the ambulances did get through to Bastogne, it seemed as if there was no end to the flow of casualties that poured into the hospital. The wounded arrived wrapped in everything from supply parachutes to table cloths, as well as civilian blankets and comforters. Plagued by hard work and so absorbed by the great drama of the Bulge, the organization nevertheless resumed operations by Christmas Eve. At this occasion the 107th was transferred back to Third United States Army, with which it would finish out the war. During the retreat (Clervaux, Libin, Carlsbourg, and Sedan) phase, the 107th Evac Hosp nevertheless managed to admit 784 patients and perform 326 surgical operations.

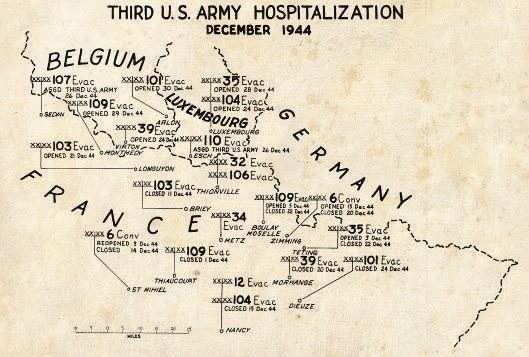

Map illustrating general distribution and locations of Evacuation Hospitals attached to Third United States Army, during the Battle of the Bulge, Belgium, December 1944.

During the last week of December the unit handled over 1,000 patients. New Year’s Day almost slipped by unnoticed had it not been for the intervention of the Luftwaffe. On that night all off-duty personnel had crowded into the Mess Hall to watch a Frank Sinatra movie. It was bitter cold outside and everyone tried to generate as much heat as possible. While the audience was first watching a newsreel showing the bombing of Helsinki (Finland), the bombing seemed too realistic. The projector crashed to the floor and glass and shrapnel scattered all over the place. After a deafening crash came a series of smaller explosions. An enemy bomber had dropped some 50 antipersonnel bombs. Everyone threw dignity to the winds and dove for shelter. Before anyone dared to rise, a hail of bullets poured into the crowded hall. Despite the fear in the hearts of those men and women, outwardly everyone was calm and collected. In the OR, Technicians and Nurses remained at their stations and continued to work. It was truly a miracle that so few casualties resulted, since only 1 man was seriously wounded and 5 slightly injured. At the end of the fighting, arrangements were made with the 64th Med Gp and the 107th Evac Hosp to fill emergency requisitions from those units. Eight (8) truckloads of supplies from the 32d Medical Depot Company were sent to the 107th for further distribution to the units which had lost most of their equipment during the German offensive.

After the Bulge had been compressed, Allied forces were swinging into the offensive, and this time they had many a score to settle. But defensive or offensive, the heavy stream of casualties continued to pour in, and when on 15 January 1945, the organization closed its doors at Sedan, it had completed the busiest month in its history. It had cared for over 2,700 patients. As TUSA elements resumed their advance it was time for the 107th Evac to move up with the advance.

On the Move again

The first forward move in three months was completed on 21 January 1945, when the hospital unit arrived at Hachy, Belgium and set up in the Pensionnat St. Joseph, formerly used as a local German Headquarters. The building was in a deplorable condition and much work and time was put in cleaning it up. Yet is seemed more convenient and easy to run and maintain. The little stoves which kept the rooms warm were convenient for sterilizing and heating. But polishing rusty iron won’t make it shine like stainless steel, nor will mopping the floor straighten out the warped boards. Thus the unsuitable housing as well as a certain let-down after a ten weeks period of intense strain made the afternoon of 22 February 1945 an ideal time for an Army inspection. The Surgeon, Third United States Army, Colonel Thomas D. Hurley, MC visited the installation. The informal greeting of a wardman didn’t help matters, on the contrary, “Hi ya Colonel, what can I do for you?” As a result, the unit didn’t receive what it considered was due credit for its previous outstanding accomplishments. Compared to their previous experience, the stay at Hachy was considered a breathing spell. During this period the organization took stock of the past, it noted individuals whose performance had been outstanding those crucial days, and Bronze Star Medals were awarded to a number of Officers and Enlisted Men during a formation.

Nevertheless, the influx of casualties was considerable, such that a number of extra ward tents had to be erected in the courtyard to accommodate the overflow; it was furthermore found that they were at the same time convenient for admission, care and early evacuation or disposition. There were a particularly large number of patients suffering from trenchfoot and frostbite (an after-effect of the rugged life, and the fighting in mud, sleet, and snow –ed). 2,300 patients passed through the 107th at Hachy. Busy days were nothing new and while accommodating the considerable flow of sick and wounded, the organization was able to resume some of the ‘luxuries’ of military service, such as passes. Many men and women went to nearby Arlon in search of souvenirs, champagne and other things … a feeling of optimism developed as the Armed Forces’ radio continued booming news of smashing victories on the Western and Eastern fronts. The Allies were on the march and the Krauts didn’t seem to have enough left to stop them.

On Germany’s Doorstep

1 March 1945 found the 107th Evac Hosp joining the advance. The hospital unit moved into the once charming city of Diekirch, Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg and opened in the Luxembourg State School, the only building to have apparently escaped serious damage. The organization was now supporting XIII Corps which was blasting its way through the Siegfried Line and pushing towards the Moselle Triangle.

It was in Diekirch, that Major Rex Trusler, MAC, joined the Hospital, soon to be appointed its new Executive Officer and destined to play a principal part in directing the unit’s affairs. It was also at Diekirch, that “lucky” Noah Gome’s name was pulled out of a hat. He was given a 30-days furlough and sent home. And finally, it was at Diekirch, that “EVAC EVENTS”, the popular unit weekly publication was launched by a few Officers and Enlisted Men, which so truly reflected the trials and tribulations, the joys and the sorrows of the 107th family. After caring for 1,500 doughboys at this station, the 107th Evacuation Hospital received orders to move into “Fortress Germany”.

Station & Bivouac in Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg – 107th Evacuation Hospital

Operating Hospital, Ecole de l’Etat, Diekirch – 1 March 1945 > 15 March 1945

Members of the command, 107th Evacuation Hospital, on leave in Paris, France. Picture taken 19 February 1945. Photo courtesy of Tom Garber.

Germany:

The middle of March 1945 was the period of lightning advances. Within only four days, Third United States Army units advanced 55 miles to where the Rhine and Moselle Rivers meet at Coblenz. Numerous large pockets of Germans were bypassed and left behind. As the hospital convoy left Diekirch and moved on to German soil it was met by a staggering scene of devastation. Vianden, Luxembourg, was still smouldering with a smell of death. A few gutted walls and heaps of rubble was all that remained of the once thriving town. The same story repeated itself in Bitburg, Kyllburg (already in Germany) and other towns passed along the way into German territory.

Now white flags in the form of towels, tablecloths, bedsheets fluttered from the few remaining guesthouses, farms, private houses, and church towers in Nazi Germany. After driving through this havoc and the remains of the Siegfried Line with its dragon teeth, numerous pillboxes and strong points, it felt good to be out in the country green with early spring coming. On its way, the convoy passed a railroad station with just one wall remaining standing. On it were splashed in big red lettering such slogans as; “Wheels must roll for Victory.” – “Victory or Siberia.” The sign that brought the biggest laugh was: “We shall NEVER surrender!” just at that time a convoy of trucks rolled by packed with a few hundred enemy PWs. These were just a small droplet of the hundreds of thousand Krauts who were paying no heed to the “Never Surrender” sign.

On 16 March 1945, the truck convoy halted in front of an orphanage outside of Mayen, Germany, some 15 miles west of Coblenz on the Rhine River (upon arrival the German Nuns were still moving their personal belongings). The 107th Evac was soon faced with a serious dilemma. As the convoy pulled up in front of the building the whole group of pathetic-looking kids faced the men, they looked like any other motherless kids, how could one throw them out. They were finally moved to nearby temporary quarters but allowed to retain the use of their chapel, bakery, and other essential rooms. Life at Mayen was not without its diversions. A beautiful stream with plenty of trout was discovered near the orphanage and the resulting fish stories were of a unique character. Many of the men insisted that the fish they caught had swastikas painted on their bellies.

At first casualties were gratifyingly low, but they soon jumped to 2,300. During the last period spent in Mayen an impressive formation was held during which Certifications of Merit were awarded to 31 men who during the Battle of the Bulge volunteered to stay behind and care for patients when the Hospital was in imminent danger of being overrun by enemy forces. Also 3 Nurses received BSMs for meritorious service. Great masses of German forces had been pinned against the Rhine and cut to pieces, it seemed that little effective resistance was encountered. As the wards had been kept tidy and ready for use, the hospital was able to open quite rapidly. German patients, now prisoners of war, received a lot of bedside care from captured German medical personnel.

A detachment of troops belonging to the 9th Armored Infantry Battalion (6th Armored Division) arrived at Buchenwald on 11 April 1945 under the leadership of Captain Frederic Keffer. The soldiers were given a hero’s welcome, with the emaciated survivors finding the strength to toss some liberators into the air in celebration. Later in the day, elements of the 83d Infantry Division overran Langenstein, one of a number of smaller labor camps comprising the Buchenwald Concentration Camp complex. There the division liberated over 21,000 prisoners, and ordered the Mayor of Langenstein to send food and water to the camp, and sped medical supplies forward from the 20th Field Hospital. TUSA Headquarters sent elements of the 80th Infantry Division to take control of the camp on the morning of Thursday, 12 April 1945.

On 16 April 1945 Colonel William E. Williams (CO > 120th Evacuation Hospital) took over KZ-Buchenwald. There were 2,180 sick in the camp when the unit arrived. The men started work on two of the former SS barracks, cleaned them out with the help of internees, installed cots, and provided blankets and medical supplies of their own issue. They also organized a separate Typhus ward in another former SS building. The first Nurses and medical personnel reached the Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 22 April 1945.

Series of pictures illustrating the building complex at Kassel-Rothwesten taken over by the 107th Evacuation Hospital, 8 April 1945. From L to R: half-destroyed buildings as discovered during stop over at the site. Vintage photo from 1934 illustrating the official entrance at “Fliegerhorst Rothwesten” then in use by the German Luftwaffe. Other picture illustrating another view of the damaged buildings as discovered early April 1945.

Stations & Bivouacs in Germany – 107th Evacuation Hospital

Operating Hospital, Mayen – 16 March 1945 > 6 April 1945

Bivouac, Kassel-Rothwesten – 8 April 1945 > 12 April 1945

Operating Hospital, Thamsbrück – 13 April 1945 > 25 April 1945

Bivouac, Weiden – 26 April 1945 > 30 April 1945

Operating Hospital, Regensburg – 30 April 1945 > 20 May 1945 (functioned as Station Hospital)

Operating Hospital, Würzburg – 21 May 1945 > 8 September 1945 (replaced by 124th Evacuation Hospital)

Gradually the Rhine battle moved ahead and orders were to arrange for a stop-over at Kassel, Germany.

The plans called for the 107th to bivouac at Kassel-Rothwesten, some 5 miles northeast of Kassel until it could be determined from the fluid condition of the front where medical support was most needed. “Fliegerhorst Rothwesten” as it was called, was a huge complex comprising buildings, hangars, airfield, built by the Luftwaffe in 1934 and captured 7 April 1945. The abandoned rooms never really seemed like to belong to the new tenants. Even when individual equipment and cots were in place, pictures and maps on the walls, clothes in the lockers, books, notes, posters, documents, murals, decorations, remained unmistakably German. The buildings were part of a Luftwaffe Flight Training School. It was easy to understand what had happened. The unexpectedly swift Allied advance had caused the enemy to leave quickly! The place was taken over by the US Army Air Forces and the IX Engineer Command which constructed new facilities (longer runway) designated Advanced Landing Ground R-12. Between April and November 1945, the airfield was used by the 48th and 36th Fighter Groups respectively.

It was on its way to Kassel that the hospital unit crossed the Rhine River via a pontoon bridge.

The bulk of the 107th reached Kassel on 8 April 1945 occupying the abandoned Flight Training School, requiring four shuttles with its own trucks in order to move the equipment, the bulk of supplies, and the entire personnel.

After four days of rest, sleeping, and relaxing the unit was on the move again. On 13 April 1945, a cold and rainy day, the trucks we on their way to Thamsbrück, moving some 45 miles to the southeast, but by the time the trip ended the sun was out. The hospital tents were neatly lined up, the painted red and white GC markers made their appearance once more, the Stars and Stripes waved out front, and everyone seemed ready to move in and start working. The new location was near Langensalza, situated on historic battlegrounds where Prussia defeated Hanover and established her dominance over Germany. The main highway ran adjacent to the hospital installations and one could look out and see remnants of the Wehrmacht trudging down the Autobahn, singly, or in pairs, some of them carrying white flags of surrender. But usually our doughboys were too busy to pay any attention to them.

Beautiful weather, and not too much work as battle casualties remained light, made the stay a nice one.

Gradually the main occupation was now receiving vast numbers of RAMPs (recovered Allied PWs) as rapidly advancing US troops overran many prison camps. Most of the recently liberated prisoners suffered from malnutrition and multiple ailments. When received, they had to be deloused, washed, and issued a complete new set of clothing, before treatment could be started. To see fellow Americans come in covered with lice and dirt, hobbling along like old men, and to meet some of the 28th Infantry Division men they had known at Clervaux, their weight now reduced by a third, talking in whispers with the manner of a beaten dog, tore the medical personnel’s heart. They just ripped to shreds the last bit of sympathy left for the Germans!

When personnel began to be able to get extra time off, and go on a few sightseeing tours, one, which will never be forgotten was KZ-Buchenwald. It was a place of filth, despair, and misery, a gray, barren place with a smell of starvation, death, and suffering, which members of the 107th could not comprehend even when confronted with it. Emaciated bodies, not more than living skeletons with staring eyes wandered around the installation. This was final proof of how Nazi Germany was running the war… many French, Russians, Poles, and other nationalities had been held at this Concentration Camp and the stories they told their liberators were hair-raising.

Group picture illustrating some members of the 107th Evacuation with a large sign indicating V-E Day. At the time the organization was located under tentage outside of Regensburg, Germany. The Hospital remained in Regensburg from 30 April 1945 until 20 May 1945.

On 22 April orders were received to move on in support of Patton’s drive. On 26 April, the unit’s advance across Germany turned southward and during its next move the 107th bivouacked for four days outside Weiden. Rumors were flying thick about the Germans having thrown the towel, but this proved wrong when on 28 April the Luftwaffe strafed the road beside the bivouac area. It was cold and rainy, the tents leaked, the ground was soggy and people circled around the stoves for warmth and comfort. Off-duty time was filled with picnic, fishing or rowing, just enjoying the sun when it made its appearance. Towards the end of the month everyone packed and after striking all tentage, the trucks and ambulances headed for Regensburg, Germany.

Just outside Regensburg the convoy ran into a thick, cold sleet storm. For miles along the road stretched PW Enclosures where thousands of German soldiers huddled together behind barbed wire, crouching in groups to keep warm. Arriving at Regensburg, Germany on 30 April 1945 the men were to set up the hospital on the banks of the Regen River, a tributary of the Danube. The advance party had left a few days ahead of the main convoy to prepare the site and make the place more livable.

Upon arrival it was decided that the Nurses would occupy a house and the Officers plus the Enlisted Men would live in tents along the banks of the river. After a nice hot meal everyone was in good spirits and ready to “pitch in”. There was some skepticism amongst the Nurses about living in between German families. This was something new! The local residents had not all departed from the apartment houses and cartloads of personal belongings were still in the process of being hauled away. Since the current indoor “water closets” were the cause of many unpleasant odors, the usual latrine was erected in the back yard of the building. Lyster bags were hitched to a tree in the garden.

The 107th was now supporting the Armies moving in for the kill. Many of the casualties resulted from the heavy fighting around Passau. But there was also a varied assortment of casualties; victims of road accidents, GIs who had shot themselves while fooling around with captured enemy weapons, and Allied soldiers and German civilians victims of mines. In all, the Hospital treated 1,900 patients at its last combat station.

The ANC Officers who occupied the kitchens (all available rooms had to be used) had quite an advantage. A few of them even tried out their domestic baking skills. If there wasn’t any other food left, whether local or that of parcels shipped by relatives, the trusty old K-ration biscuits would appear. Much to the chagrin and annoyance of a few Nurses, bed bugs were eventually found and the rooms had to be fumigated.

Down along the river bank other activities transpired. During off-duty hours, some personnel spent time in absorbing the sun’s rays, while others preferred swimming or boating..

On 8 May 1945 the unit was greeted with some excellent news – it was V-E Day! It was the best news everyone had heard in a long time. Even before V-E Day bells stopped tolling, rumors were flying, where would the unit go, what would happen to staff and personnel, would the hospital transfer to the Pacific?

Series of pictures illustrating different sctions of the 107th Evacuation Hospital. Top L: Motor Pool personnel. Top R: Laboratory, X-Ray, and Pharmacy personnel. Bottom L: Headquarters and Medical Supply personnel. Bottom R: Detachment personnel.

Even though the war was over in Europe the 107th had some of its busiest days on duty. Recently liberated and recovered Allied prisoners of war (RAMPs) were still being brought in from the Oflags and Stalags. To be confronted with those half-starved and sick soldiers really brought tears to many.

Startling was the fact that among about every fourth case admitted to the hospital there was a soldier suffering from a self-inflicting wound (SIW –ed) whether voluntary or non-voluntary was difficult to appreciate. This all happened after V-E Day. It really looked as though the soldiers had more time to play with German souvenirs which they knew little about. Other accident cases were admitted as well, including a number of local children victims of German booby traps, mines or abandoned weapons and ammunition. To many however, it looked like peace had come to Regensburg!

During the last weeks of May 1945, the 107th Evac was ordered to proceed to Würzburg and begin to operate under Station Hospital conditions. Upon arrival the organization was able to occupy a 1000-bed a modern German Military Hospital, one of the remaining structures of an otherwise pulverized and burned out town. At first it seemed as if one would get lost in the vastness of this 1300-room institution, but soon a homier feeling developed, no doubt helped along with the new painting of the huge German eagle and swastika dominating the front entrance, now painted in appropriate red – white and blue, which some Germans didn’t like.

Everything was done to make the unit’s stay comfortable, as Colonel H. W. Daine had promised his men. Eating from chinaware was new, and being accompanied by an Italian DP orchestra was also a treat. Everyone patched in to beautify the place, and soon the lovely lawn and garden looked like green velvet.

Points were now counted and recounted. Men with ASR scores above 85 points, wondered whether the Army was really going to send them home, and at intervals, some high pointers indeed left for that “promised land”!

Softball became one of the leading sports, and even the Nurses came out of the cheering section and decided to participate. Then came volleyball, ping pong, and swimming, with all these activities culminating in a formidable Track and Field meet. A unit educational program was launched with classes in foreign languages, science, and arts. A surprising number of Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men even began to take piano lessons and attend performances by German artists. Some of the Nurses and EM were lucky to be able to take courses at civilian Universities.

Clubs began to spring up. It all started with Officers’ Clubs, soon followed by NCOs and Privates who organized even more elaborately decorated and furnished club rooms, while the ARC Recreation Hall for patients became one of the finest of its kind. These Clubs with their bars and entertainment programs soon became the center of the organization’s social life.

Despite all of this, it was a period of great restlessness and perhaps the most painful period in the history of the 107th Evacuation Hospital. Desperately anxious as everyone was to return home, the 107th was breaking up…