12th Evacuation Hospital Unit History

Portrait of Major General James C. Magee, US Army Surgeon General, 1939-1943.

Introduction & Activation:

Under the “Affiliated Hospital Program” begun in World War I, the Army Surgeon General, Major General James C. Magee, worked with civilian Hospitals (many connected to Universities –ed) to recruit Doctors and Nurses in groups, thus providing key staff for new military hospitals at once. However, this program (along with other medical reserve programs) lapsed during the interbellum years. By the end of the 1930s, and especially during 1940 – 1941, when Germany was conquering much of Western Europe, the Medical Department stepped up its work with major civilian hospitals to recruit medical professionals into affiliated reserve units. These volunteers eventually became the professional core, leaving only a few key Officers (a command group and some supply and administrative Officers) plus the bulk of the Enlisted personnel to be provided by the Army (main source: Medical Training Centers). With these Army personnel added, the medical professionals, already formed into teams, could continue their work uninterrupted once they stepped into uniform.

In the first year and a half of WWII the Medical Department had to provide hospitalization facilities for reinforced US garrisons in overseas Departments and Bases, and for Task Forces engaged in operations against the enemy. Meanwhile it had to organize, train, and equip other medical units for use when the Army should become engaged in full-scale offensives. Early in 1942 the Pacific Theater required hospital units, and in the summer the emphasis shifted to the European and the North African Theaters of Operations, and therefore hospitals were deployed to these Theaters in increasing numbers.

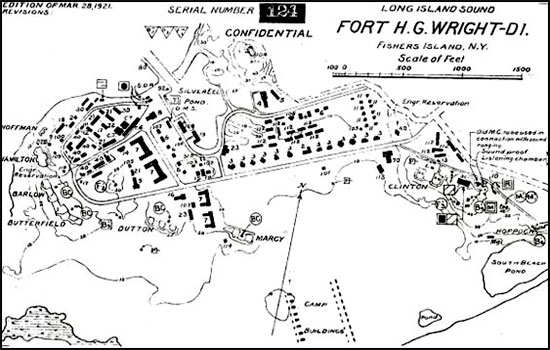

Layout map of Fort Horatio G. Wright, Fisher’s Island, New York, where the 12th and 19th Evacuation Hospitals were combined in 1942 to form a single unit.

The 12th Evacuation Hospital was reconstituted through these efforts, replacing the previous organization set up in Boston, Massachusetts, under the same name (in WWI, the German Hospital of New York City organized a hospital for the Army; however, as it was composed largely of Americans of German ancestry it was not deemed possible to be sent overseas, and in 1918 the hospital conveniently changed its name to Lenox Hill Hospital).

On February 16, 1942, the Board of Lenox Hill Hospital agreed to start recruiting personnel for an Army Evacuation Hospital, with initial action taking place throughout the spring. Reflecting a much different status in the community since World War I, the hospital organized a send-off dinner for staff at the posh Hotel Astor on June 19, after which the unit was officially activated on August 12, 1942.

The Lenox Hill Hospital recruited 32 Doctors, 34 Nurses, and 10 Enlisted Men, but the unit needed 47 Medical Officers (including administrative and command personnel), 52 ANC Officers, and 318 Enlisted Men to reach its authorized strength as per T/O 8-580 dated July 2, 1942. To fill the gaps, the War Department merged the 12th with the 19th Evacuation Hospital, a training organization numbering only 5 Officers and 294 EM personnel (the latter was activated June 1, 1941, and supplied Enlisted personnel to both the 7th Evacuation and the 12th Evacuation Hospitals –ed).

Organization:

Evacuation Hospitals were the vital link in the chain of evacuation; they could handle major surgical and medical procedures for all casualties. Such units were capable of handling more specialized cases and were provided with:

- 1 Maxillo-Facial Team

- 1 Neuro-Surgical Team

- 2 Orthopedic Teams

- 2 Shock Teams

- 3 Surgical Teams

- 1 Thoracic-Surgical Team

Military convoy during the 1942 Second United States Army Tennessee Maneuvers.

The Evacuation Hospital was split in Administrative and Professional Services. Officers were distributed over the Administrative Service as follows:

- Headquarters > 4 Officers

- Registrar and Detachment of Patients > 2 Officers

- Receiving Section > 2 Officers

- Evacuation Section > 2 Officers

- Mess Section > 1 Officer

- Supply and Utilities Section > 2 Officers

Officers serving with the Professional Services were as follows:

- Medical Service > 6 Officers

- Surgical Service > 22 Officers

- Laboratory Service > 1 Officer

- Roentgenological Service > 2 Officers

- Dental Service > 2 Officers

The ANC Officers in the Administrative Services numbered 6, while those working in the Professional Services totaled 46.

Thirteen (13) Enlisted personnel served in Headquarters; a total of 165 Enlisted Men were at work in the Administrative Services and another 140 EM served with the Professional Services.

Each Evacuation Hospital consisted of 1 Commanding Officer, 1 Executive Officer, 1 Chaplain, 1 Quartermaster Corps Officer (in charge of non-medical supplies), as well as 1 Chief Nurse and 1 Assistant Chief Nurse, and in addition to the medical personnel, 1 Dietitian (civilian). The latter received a commission as of March 31, 1943.

Photo of RMS Queen Elizabeth taken in July 1942. She carried the 12th Evacuation Hospital to the United Kingdom, sailing out of New York POE January 6, 1943 with destination the United Kingdom.

Evacuation Hospitals were set up about the same as they had been in the Great War. Patients arrived at the Receiving Section, where they were examined (triaged –ed) and prioritized; surgical patients would go to the X-Ray or Shock Ward (if needed), then to the Operating Room, and finally to the Recovery Wards. Medical patients went straight to the Recovery Ward after receiving the necessary treatment. However, COs arranged their hospitals to fit local circumstances and their own preferences. Evacuation Hospitals also contained a Kitchen Detachment (which prepared meals according to patients’ needs), and other general Administrative Sections.

The US Army Medical Department deliberately kept units lean, with essential personnel and equipment only; non-essential resources were therefore attached. Some examples; Evacuation Hospitals had neither laundry capability nor water supply, which proved impractical, therefore Laundry Platoons were often temporarily or permanently attached to the organization. Any major construction work was left to the Corps of Engineers.

Training:

The 12th and 19th Evacuation Hospitals were combined at Fort Horatio G. Wright (series of coastal gun batteries established in 1898 in Suffolk County, New York, part of the harbor defense of Long Island Sound –ed), situated on Fisher’s Island. After 2 weeks of routine unit training (during which family members could visit the New Yorkers in the unit), the 12th Evac entrained for Tennessee. Upon arrival it was based at a former Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) campsite near Portland (north of Nashville and close to the Kentucky border), where it was instructed to support Second Army units training in the Tennessee Maneuver Area.

The currently empty CCC buildings were used for the hospital itself, with tents used for living quarters. In its 2-months stay, the organization received about 1,000 patients with a range of different medical problems, as well as some trauma and burn cases suffered during the maneuvers. Any problems with the water supply and drainage were readily solved on site.

Training in the field not only taught the 12th Evac how to work with field equipment, but also gave members some welcome experience working together as a unit. Personnel also had free time for entertainment, such as visits to Mammoth Cave. Because of fluctuations in the Army personnel system, the 12th had gone to Tennessee slightly understrength, but by the end of the year was marginally overstrength.

US Forces build-up in the United Kingdom. Outside depot in the country illustrating miscellaneous types of bulldozers.

Due to personnel and equipment restrictions and shortages, some of the Evacuation Hospitals were converted from 750 to 400-bed units before being sent overseas. Some units were never activated with personnel being re-assigned to other units. Quite a number of Surgical Hospitals were re-designated Evacuation Hospitals prior to overseas deployment.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

The 12th Evacuation Hospital left Tennessee on November 12, 1942, traveling by train to Fort Devens, Ayer, Massachusetts (Military Reservation; total acreage 11,796; troop capacity 2,066 Officers and 33,232 Enlisted Men –ed), about 30 miles west of Boston. There the unit spent 6 weeks of training and preparing hospital and personal equipment for shipment overseas. Training included road marches, hikes, and calisthenics for improving physical fitness, as well as reviewing of medical and administrative problems encountered in the field, while in Tennessee.

On Christmas Day, the unit learned they had just 24 hours to prepare for departure. At 045 the next morning, the 12th Evac entrained for Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey, the Staging Area for the New York Port of Embarkation, outside New York City.

On the evening of January 5,1943, the Hospital boarded RMS “Queen Elizabeth”, which sailed during the night of January 6, 1943. The “Queen Elizabeth” sailed alone, relying on its high speed and zigzag maneuvering to avoid any enemy submarine attacks, and arrived safely at Gourock, Scotland a week later, on 12 January 1943. The crossing was uneventful, despite crowding conditions among the Enlisted Men and general dissatisfaction with the British food served on board during the journey. The liner had 12,000 troops on board, among which the 56th Fighter Group and the 33d Air Service Group, both pertaining to the Army Air Forces.

United Kingdom:

The first few months in England involved no actual hospital work. Sent to the southwest of England (Honiton, in East Devon), the organization moved into uncomfortable British prewar barracks outfitted with wood-plank cots and straw-filled mattresses.

With no active US Army hospital nearby, training consisted of physical drill and classroom instruction. While Enlisted Men received cross-training on basic patient care, most of the Officers attended some kind of professional course on topics such as blood transfusions, mess-hall management, dentistry, or general war medicine. A brief flurry of increased activity occurred in February as the Allied High Command contemplated plans for a possible invasion of France in the summer of 1943. In preparation for the invasion, the 12th Evac was issued equipment and began establishing a hospital about 40 miles further east, but the operation was called off. Meanwhile the Allied build-up in the United Kingdom continued unabated.

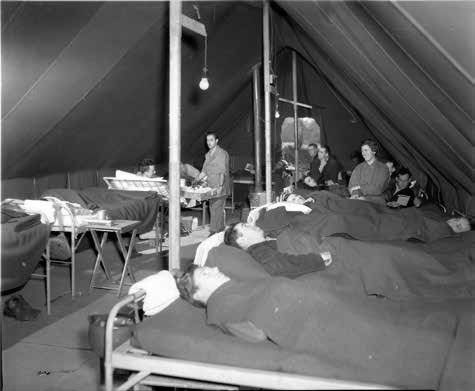

Patients at the 12th Evacuation Hospital, Carmarthen, Wales, United Kingdom, where the organization operated from October 1943 until March 1944.

Operation “Bolero” came into being in April 1942, more than two years before the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. Its purpose was the transfer of fighting men and equipment from the United States and Canada to England to support an envisioned cross-Channel invasion in 1943. Before Allied Forces became strong enough to gain and maintain a lodgment on the European continent, a massive build-up of American troops and supplies would be required to support such an important endeavor. The Army Services of Supply (SOS) were given responsibility for the colossal logistical effort. Just getting the fighting men and materiel to the United Kingdom was quite a challenge in itself, but feeding, clothing and housing the soldiers once they reached Great Britain was an even bigger challenge. Simply storing the thousands of aircraft and vehicles including all kinds of supplies being brought over across the Atlantic meant that every vacant field in England was a potential storage area.

In April the 12th was split into two groups to operate 2 hospitals supporting US bomber forces in the east of England; both hospitals served until October 1943. Because Evacuation Hospitals were designed to work in one place, cross-training was needed to provide enough men to handle key functions in two separate places. However, this training was not lost and later proved useful during the speedy advance across France. Both hospitals operated in Nissen huts: semicircular, galvanized iron buildings that were cheap, durable, and easy to construct. In the 6 months that the organization spent in eastern England, it made its bases more comfortable by adding and constructing Officers and EM clubs, barber shops, and a Post Exchange. United Service Organizations (USO) entertainment shows were held nearby, and “Liberty” tours were organized, visiting neighboring cities for dances and movies. A vegetable garden was started to augment the food supply, and landscaping was done as well.

Most of the medical work was routine, consisting of care for outpatients or sick people. The Eighth Army Air Force was not yet the “Mighty Eighth,” so battle casualties were limited. Nevertheless, serious injuries were occasionally seen, mostly involving air crews.

While in England, personnel voiced some dissatisfaction with the command structure. Some Lenox Hill Hospital Doctors wrote to their civilian counterparts complaining about the Hospital CO, Regular Army Colonel Rawley Chambers. Chambers was variously reported as physically unfit, lacking stamina, having considerable mental instability, and generally lacking character and ability to command. An unofficial inspection took place in England, and the Officer was eventually replaced. (R. Chambers went on to command a Hospital Center and after World War II, became a Brigadier General).

The Chief of Surgery, Lieutenant Colonel Otto Pickhart (who had served in Base Hospital 12 in World War I, continued in the National Guard, and organized the group from Lenox Hill Hospital), took charge after a short time. When Lt. Colonel O. Pickhart fell ill in the spring of 1944, the Chief of Medicine, Lieutenant Colonel Marshall S. Brown, Jr. (also from Lenox Hill Hospital), became the new Commanding Officer.

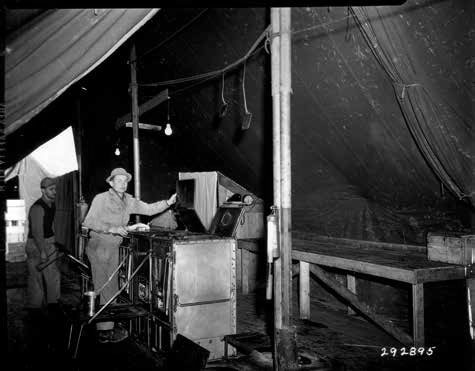

Main kitchen at the 12th Evacuation Hospital, Carmarthen, Wales, United Kingdom.

Change of Station:

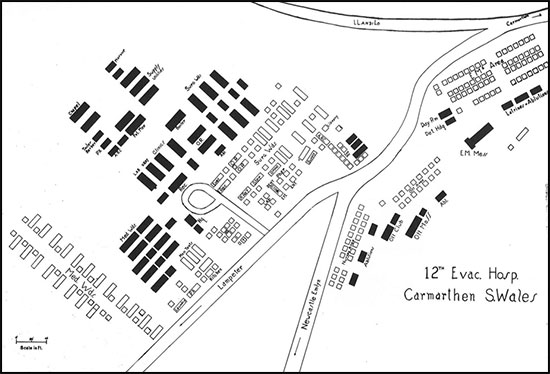

In October 1943, still under command of Lt. Colonel O. Pickhart, the 12th Evacuation Hospital was sent to an empty cow pasture in southwest Wales near the town of Carmarthen. Its job was to set up and operate a station hospital, first working under canvas and then gradually moving into huts as they were built. This experimental operation was related to plans for invading the continent: since the Army would require Station Hospitals in France and needed to know how well these medical units could function under tentage. Troops called the unit the “guinea pig hospital” in press interviews. In England, Station Hospitals handled routine illnesses and injuries for personnel stationed in a particular area, and later became crucial in caring for the Allied Expeditionary Force on the continent.

Upon arrival in Wales, the 12th faced an empty field with poor drainage, with fewer personnel than Station Hospitals normally had for labor, inadequate equipment for a bare field site, and a rigid plan from Headquarters for the location of each tent and building. These conditions were worse than a Station Hospital would actually face in France, but in Wales, the 12th Evac was running a test and had strict criteria to meet.

The first few days were spent pitching the necessary tentage, connecting water pipes, electricity, and telephones; and building paths and roadways. On October 20, 1943 (only 14 days after arrival), the Hospital received its first patients, and more arrived as additional ward tents were being readied. With the assistance of a detachment from the 95th Engineer General Service Regiment (Colored) gravel roads were laid, concrete pads poured for hutments, gaps bulldozed, and water pipes laid. Poured concrete floors also improved overall sanitation.

By January 1944, Nissen huts had been built and the remaining tents had been winterized with plywood and bracing. Experienced personnel who had been through the Tennessee Maneuvers in the ZI complained less about the living conditions than the recent transfers or replacements who had never had to live the experience.

The 12th made the experiment a success through hard work, improvisation, and working around Army supply channels. Many pieces of equipment that turned out to be important were not authorized, including such ordinary utility items as latrine buckets, chairs, lanterns, stoves, and tables. Living conditions started out rough but improved gradually. No baths or showers were available at first, and laundry was a problem. Unit training continued with road marches, French and German language classes, chemical warfare defense training, and aircraft identification, which were all courses required in preparation for the invasion. The locals were friendly, inviting Americans to social functions in town and attending dances and parties organized at the unit. The 12th Evac reciprocated by organizing a grand Christmas party for 400 local children. Passes and leaves were also available to the personnel of the command, and there was a library, a movie theater, and USO sponsorship of tours. The American Red Cross workers ran programs for patients, keeping up their morale. Over the winter, the 12th re-organized slightly, losing 4 MAC Officers and 15 Enlisted Men as the Army changed the structure of Evacuation Hospitals.

Map illustrating the general layout of the 12th Evacuation Hospital, Carmarthen, Wales, United Kingdom.

On March 25, 1944, the 12th handed the Carmarthen facilities over to the 232d Station Hospital (Hospital Plant 4184) and moved to the northwestern part of England. Overall, the test taught the 12th how to live in the field and how to solve problems for themselves. The unit did have engineer support, but it was limited and fairly representative of the engineer support it would receive in the future. There were limitations; if a hospital was needed somewhere quickly, there was no opportunity to spend 3 or 4 weeks on engineering work.

For a month the 12th Evac was billeted in the town of Sale, Cheshire, approximately 5 miles southwest of Manchester. No hospital plant was set up at Sale, and the unit’s Commander decided to give his men some rest, partly because the 12th did not have enough equipment for a full training program. Mornings were used for training, alternating road marches with classroom instruction, and afternoons were reserved for athletics and recreation. The local population organized a “welcome club” on the unit’s arrival and remained hospitable throughout their stay in the area.

Preparations in view of D-Day:

By mid-May 1944, preparations for D-Day, the Invasion of France, were well advanced. The 12th Evac moved to Moreton Park, Dorset (Hospital Plant 4155, APO # 403 –ed) close to the south coast (area of Portland-Weymouth –ed). Plans called for the 12th and 109th Evacuation Hospitals to be detached from TUSA and serve as holding units (transit hospitals –ed) for casualties returning from France, providing treatment and stabilization before evacuation continued to General Hospitals further north in England, where patients would receive definitive surgery and recuperate. At Moreton, the staff of the 12th were happy to find level, well-drained ground with hard sod above gravel, in contrast to the mud experienced at Carmarthen. Although engineers had already laid out roads, constructed walkways, and poured concrete for tent bases, water was brought by tank truck from the nearby River Frome (the 305th Station Hospital, Hospital Plant 4113, APO # 873, was established at Frome, Somerset –ed), and personnel had to use the river for bathing. The 12th also adapted to working with limited Evacuation Hospital equipment instead of the additional items and quantities authorized for the less mobile Station Hospitals. Improvisation was the norm; tables, chairs, and benches were made from shipping crates, and external fuel tanks from damaged aircraft were converted into water tanks and hot water pans for the food line.

For protection, trenches were dug against German air raids near the south coast (barrage balloons, antiaircraft artillery and searchlights were set up in the area). The organization arrived in Moreton about 3 weeks before D-Day. After spending 2 weeks preparing the Hospital, pitching temporary tented plants side-by-side, personnel waited, played sports, wrote home, and watched endless road convoys of troops and vehicles passing by on their way to the embarkation ports. At about 2300 hours on the evening of June 5, hundreds of aircraft passed overhead, carrying Allied Airborne Divisions into Nazi-occupied France.

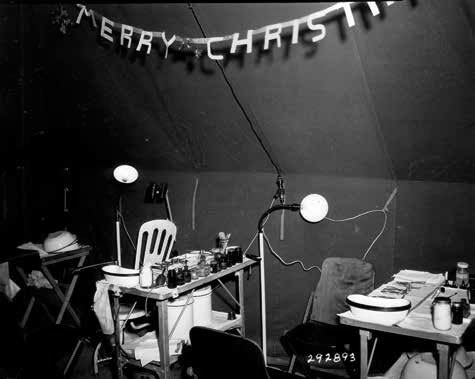

Eye, Ear, Nose, Throat Clinic (EENT) of the 12th Evacuation Hospital, Camarthen, Wales, United Kingdom, Christmas Eve, December 24, 1943.

The 12th Evac began receiving casualties at midday June 7, 1944, mainly wounded soldiers of the 90th Infantry and 101st Airborne Divisions evacuated via Utah Beach. The next day a first batch of German prisoners-of-war were in the mix. For the first time, the Hospital had to work full 12-hour shifts as the patient census continued to increase. Between June 8 and June 30, 1944, it received 1,309 patients and performed 596 operations, averaging 60 admissions and 27 operations per day. Personnel also had to handle evacuation out of the Hospital, borrowing ambulances and using off-duty soldiers to carry litters and drive patients to the Hospital Trains that stopped about 4 miles away. Some personnel who had volunteered for special duty in April finally learned their assignment: to operate on specially-equipped Landing Ships Tank (LST) bringing back casualties from the invasion beaches. On each LST, an Army Surgeon (assisted by 2 Surgical Technicians) performed surgery while two Navy Doctors (aided by 2 Navy Corpsmen) handled all the patients on cots. The 10 men selected from the 12th Evac (4 Surgeons and 6 Technicians) were already detached in May 1944, working at several hospitals to refresh their skills and build up teamwork.

From D+1 (June 7) onwards, the LST (H) ships shuttled across the Channel, carrying reinforcements over and returning with the wounded. Round trips took 24 to 48 hours, as the ships landed in France, unloaded their passengers through the bow doors, loaded for the return trip, and waited for the next high tide to make the trip back. Overall, the men on DS from the 12th Evac averaged four roundtrips, and one member, Private Edward R Bloch, was slightly wounded when a naval mine damaged his ship. Despite his wound, Bloch helped move the wounded to another ship and stayed with them to provide first aid. He received the Purple Heart, the only member of the 12th Evacuation Hospital to be awarded the medal during World War II.

The Hospital closed down for operations pending its movement to France. Showdown inspections were held to ensure that the staff had the complete set of personal equipment and no unauthorized items. Hospital equipment for the relocation arrived slowly due to severe and Theater-wide shortages of some specific items, which delayed final packing. As equipment came in, items were packed into special large wooden crates that compartmentalized wards or departments to make it easier to locate and identify supplies on arrival.

Throughout July, the organization overhauled its vehicles and equipment, packed, and completed training.

On July 29, 1944, all vehicles, drivers, and equipment were moved to Southampton. Personnel left the next day, with the Enlisted Men marching 4 miles and the ANC Officers riding in trucks. On the afternoon of July 30, 1944, all the staff embarked on a British transport that steamed across the English Channel the next morning. Officers and EM men were fed enroute from different messes, and Nurses were assigned cabins while the men had to find somewhere a free spot to stretch out during the night. The journey was uneventful although scenic: the weather was clear and the sea placid as the ship steamed past Omaha Beach, now cleared of D-Day’s bloody debris to serve as a landing point for troops, vehicles, and supplies, and finally anchored off Utah Beach. The 12th Evacuation Hospital had reached the continent!

France:

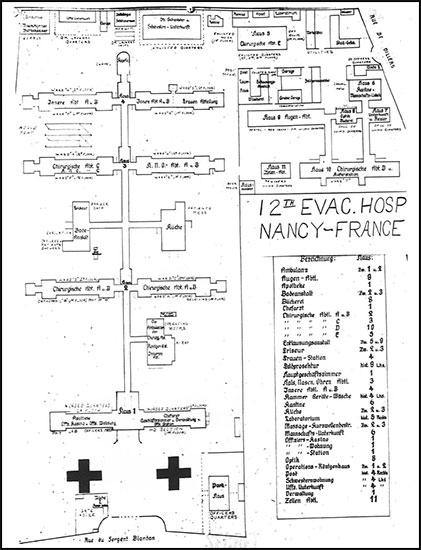

Layout of the 12th Evacuation Hospital at Nancy, Lorraine, France. Data superimposed on captured German map (Hospital previously used by German Wehrmacht).

The first week in France was quiet. The 12th bivouacked in rear areas, setting up only administrative tents (including Headquarters, a Mess facility, and Storage tents), and the EM slept in pup tents. It was clear that most of the area had been fought over; villages were damaged or sometimes destroyed and burnt-out vehicles had been pushed off the roads. The unit set up portable showers, a luxury during the hot August weather. ARC clubs were already active nearby, and some beaches were now open for swimming.

On August 8, 1944, Colonel M. S. Brown received movement orders from Third United States Army Headquarters. General Patton’s forces had just broken through the German lines near Avranches and were advancing fast. German resistance was patchy, but TUSA still needed forward hospitals to avoid long ambulance hauls from the front lines to the rear. Within 8 hours of receiving the orders, the 12th Evac was already moving on borrowed transportation. It drove past the German counter-attack at Mortain, within earshot of artillery fire, and stopped at a large château outside the village of Ernée. However, the Hospital could not be set up because supplies had been shipped separately and were still missing. Ambulances brought in some patients nonetheless, and the medical staff did what they could before sending the patients further back. Several surgical teams were therefore detached and sent to nearby operational hospitals. Some German paratroopers were captured in the area, although none ever endangered the installations. Patton’s armored spearheads advanced rapidly across France, and after only 5 days, the 12th Evacuation Hospital was left too far to the rear. On August 15 a reconnaissance party scouted a location some 73 miles further, on the eastern side of Le Mans, where the organization again bivouacked on the grounds of a château. However, the Hospital had to keep following the fast-moving Third US Army and were instead instructed to find a site close to the city of Chartres. Colonel Brown chose the village of Bonneval, another 62 miles east. The staff tried to borrow trucks from other hospitals to make the move, but it was nearly a week before enough transportation could be arranged for. On August 21 sufficient trucks had arrived (borrowed from the 94th Medical Gas Treatment Battalion) to shuttle the personnel and equipment forward to Bonneval. (TUSA Army ultimately formed an informal medical transport battalion with trucks taken from various medical units. It was the only way to move hospitals forward, since the bulk of the Army’s transportation units were mostly busy hauling other units and supplies).

Somewhere in Alsace-Lorraine, France. A medic helps 2 wounded soldiers to an Aid Station set up in the field.

The first party to arrive in Bonneval included a staking team that surveyed the site and planned the location of tents and facilities. While remaining personnel and equipment were en route on August 23 (the first time since departing England that the transportation system brought the 12th and its equipment together), orders arrived that the Hospital must be ready to receive patients the same afternoon. In a whirl of activity, supply crates were checked and shortages identified: a few beds and water cans were missing, but more important were 130 missing tent poles. One group began setting up tents while others went to a nearby forest and chopped down young trees as replacement tent poles. With these substitutes, troops worked through afternoon rain showers into the evening. Because labor was short, the 12th resorted to two expedients: first, they borrowed 40 German prisoners from a nearby enclosure for heavy labor and digging; second, they changed their views on what qualified as “woman’s work” and the nurses pitched in. The 12th was ready when patients began arriving at about 1930 hours.

The first patients were mostly transfers from other hospitals that were moving forward. Few of them needed surgery, but some operations were performed overnight. By the next day, the 12th was the main operational hospital in the area and patients flooded in: 439 in the first 24-hour period. The majority were Enlisted US personnel, but some were French troops and German prisoners. When the 12th closed down (late on August 29), it had received 1,260 patients in 6 days.

Several organizational problems were sorted out in this busy week, ones that had not appeared earlier when the 12th was operating in friendlier circumstances back in England. Some problems were relatively minor, such as improvising special diets for patients when the crate of special ration components had been lost in transit. In response, the cooks mixed and matched items from available rations and bought items from nearby French farmers.

Lighting was a bigger problem. The gasoline lanterns clogged up when filled with leaded gasoline, and the 12th’s electricians had to run cables to each of the wards for electric lights. Although there was plenty of cable, it was packed separately from the tents, and it took time for the two electricians to hook up each ward tent. A partial solution for the future was splitting up the cabling so it could be installed when each tent was erected. The lack of laundry facilities was permanently remedied when a platoon from the 452d Quartermaster Laundry Company was attached. The lack of local water supply was solved by temporarily borrowing water trucks and filling trailers. Extra personnel were borrowed from two other medical units: an ambulance company and a medical collecting company. The American Red Cross staff could speak French and helped interpret for the French patients. Caring for German PWs was an unpopular but inevitable routine duty.

Overall, patient treatment and evacuation progressed smoothly. When orders to close down arrived on August 28, 1944, non-transportable patients were transferred to a holding facility (another medical gas treatment battalion, which acquired various other functions because no poison gas was used), and an advance party set out for Donnemarie on August 30. On its way east, a jeep from Third Army Headquarters overtook the column and gave a new destination: Bergères-les-Vertus, roughly 155 miles away and approximately 62 miles east of Paris. The advance party arrived at the new location before dark, quickly surveyed a site, set up their tents, and settled in for the night. The Allied advance across France was moving so rapidly that isolated parties of Germans remained behind, and one of them stumbled into the 12th that night. When challenged, the Germans split up and ran among the tents, and when a nearby group of French Resistance fighters heard the commotion, shots were fired around the Hospital. A few bullets penetrated a tent, but nobody was hit except one German soldier, who was then captured. The next morning, the remaining Germans were rounded up by some nearby quartermaster troops, and the excitement was over. On August 31, the second element of the Hospital arrived and more tents were pitched, including the main operating sections. But General Patton’s drive across France was still in high gear, and orders arrived on September 1 to pack up and move to Reims, another 44 miles closer to Germany.

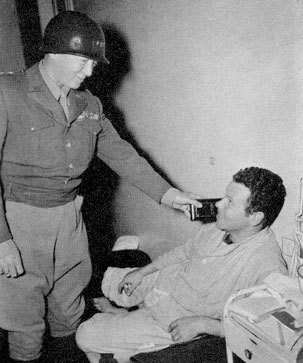

General Dwight D. Eisenhower awarding the DSC and Purple Heart to patient Colonel Dwight T. Colley, November 15, 1944, during the 12th Evacuation Hospital’s stay in Nancy, Lorraine, France.

Because the invasion of France had moved faster than planned, the US supply system was close to collapse. TUSA had driven as far and as fast as it could, keeping the enemy off balance. General Eisenhower, now Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, decided to cross the Rhine (the last major river where the Germans could form a natural defensive barrier) further north instead of continuing Patton’s advance. Part of the plan was a three-division airborne drop to seize critical bridges ahead of ground forces. This decision diverted the transport aircraft that had been providing gasoline for Patton’s forces, and the Third Army inevitably came to a halt.

The halt left the 12th Evac in disarray: lead elements had reached Reims and begun occupying a civilian hospital; a second group was stranded without transport at Bergères-les-Vertus (although some personnel hitched rides into Paris to see the French Capital), and some elements remained at Bonneval, almost 157 miles behind by the shortest roads. The group at Reims realized it was too far behind the front to function as an Evacuation Hospital, so it continued cleaning up what the hastily retreating Germans had left behind: bodies still in the morgue, body parts in the operating room, and food rotting in the kitchens and on trays. Although TUSA soon gave the Hospital a priority for gasoline, only 50 gallons were produced. Creative scrounging of gasoline from several depots in Normandy provided enough to fill the trucks and reunite the 12th at Reims on September 4, 1944. It must have seemed routine that as soon as the 12th Evac was reunited, orders arrived for another move forward, to an area near Verdun called Vadelaincourt, 68 miles to the east.

Previously, the 12th Evacuation Hospital had operated behind the Third Army in an area largely comprising logistical and support units; now the Hospital was moving into a Corps rear area, with reserve combat units and artillery in addition to support units. The Hospital’s new location at Vadelaincourt had been a hospital site in World War I, already supplied with underground drains and hard-surfaced roads branching through the area. The troops worked through rain showers to set up the Plant, which became operational by dusk on September 9, 1944. The 12th worked at Vadelaincourt for almost 3 weeks, handling a steady flow of patients that kept the receiving section open around the clock. Patients were kept only 2 or 3 days, until they were clearly stabilized. All patients were given a shot of penicillin, now more common thanks to increased production. Living conditions were fairly good at Vadelaincourt, with USO shows, movies, an ARC “clubmobile” coming by to serve coffee and donuts, the Third Army band playing concerts, and records playing over the PA system. To help with labor, 40 German PWs were assigned, but 41 were returned after a German straggler slipped into camp looking for food.

The next move was ordered on September 29, some 87 miles south and east to the city of Nancy. The Hospital traveled around its World War I operating area, and again passed close to the battle lines. The site at Nancy was a French military hospital that had been used by the Germans, a modern facility with steam heat, piped gas, and hot and cold running water in all the wards. Initially all the German furniture was simply moved outside and American equipment set up inside, but as more beds were needed, the German material was picked over and the better pieces re-used. Most of the unit arrived on September 30, and the Hospital was operational as of 1200 hours on October 1, 1944; by that evening 312 patients were being treated.

Although the 12th was now closer to the front lines and received battle casualties straight from combat, it was also close to various headquarters and treated many sick-call patients. The Hospital premises were also used for billeting brass visiting Patton’s Headquarters.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr. (L), Lieutenant Colonel Marshall S. Brown, Jr. (behind CG TUSA), and General Dwight D. Eisenhower, CG SHAEF (R), while visiting patients at the 12th Evacuation Hospital, Nancy, Lorraine, France, November 22, 1944.

Because of the change in mission from treating battle casualties only, the 12th was augmented with other units. Elements of the 59th Field Hospital expanded the available ward space, a dental prosthetics unit was attached, and extra Doctors and Nurses were assigned, including neurosurgical and ophthalmologic teams for specialized cases. Although psychiatric care was normally unavailable in Evacuation Hospitals (care was concentrated further forward for those who could quickly return to combat or further back for those needing longer recovery), neuropsychiatric wards were added to the 12th. An engineer company helped with maintenance work, a Utility Officer was assigned, and French civilians helped with Red Cross activities.

Life was quite comfortable for personnel; not only were German prisoners used for labor, but French civilians were hired, some of whom staffed a beer parlor for Enlisted Men. General Dwight D. Eisenhower stopped by the Hospital November 15, 1944 to present a Distinguished Service Cross and Purple Heart; a Congressional delegation visited; and a number of two-star Generals came and went. Ike returned and was joined by Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr. November 22, and both General Officers visited some of the wards. There were exciting moments, such as the night of October 24 when a shell from a German long-range gun landed between three buildings. Fortunately, it failed to explode and instead buried itself 33 feet deep in the ground, requiring 4 days to excavate and defuse.

On October 30, 1944, ten Enlisted Men were issued weapons, the first weapons issued to the unit. Casualties dwindled, however, as TUSA was slowed down by continuing supply problems and the forward hospitals became able to hold patients longer (up to 3 weeks). Therefore, more troops in the Third US Army than in other units recovered and returned straight to their units, rather than recovering in rear-area hospitals and being returned to any unit that needed soldiers. By early December 1944, the Allies were pushing further into the Siegfried Line (Westwall –ed) fortifications, and the 12th was scheduled to move forward to Sarralbe, about 37 miles closer to the front. While Allied forces moved forward, the Germans strongly resisted and the overall advance was slow. This gave the unit plenty of time to organize its move, and engineering repairs were planned ahead of the departure.

These plans were disrupted, however, when the Germans launched a major surprise attack December 16, 1944, which became known as the “Battle of the Bulge”. As the enemy pushed American units back and surrounded the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne, Belgium, the Third Army revised its military and medical plans. Instead of continuing the advance eastward, George S. Patton wheeled a Corps north and counter-attacked the Germans. The smaller hospitals followed, because it was easier for them than for a 750-bed unit to pack up and move, and find a suitable site to operate. Not until the first week of January 1945 did the 12th Evac actually start moving north.

November 22, 1944. Lieutenant General G. S. Patton, Jr., CG Third US Army, visits the 12th Evacuation Hospital to award medals to wounded servicemen.

Battle of the Bulge & Operation “Repulse”:

By January 1945, a handful of men from the 12th had already gone into action. On Christmas Eve 1944, German forces surrounded American forces cut off at the key road junction in Bastogne. TUSA staff called the closest hospital—the 12th Evacuation Hospital —and asked for a volunteer surgical team, and many men stepped forward. Four were chosen: 2 Surgeons; Captains Henry M. Hills and Edward N. Zinschlag, and 2 Enlisted Men; Technician 3d Grade John H. Donohue and Technician 4th Grade Lawrence T. Rethwisch, planned to parachute into the pocket at Bastogne. However, since these men lacked proper parachute training, they would reach the front by glider on the afternoon of December 26. Departure took place from airstrip A-82 at Etain, France. The Third US Army Surgeon’s office also obtained 2 extra Medical Officers (Major Lamar Soutter and Captain Foy H. Moody) and 2 Enlisted Men (Technician 3d Grade Clarence C. Matz and Technician 4th Grade John D. Knowles) from the 4th Auxiliary Surgical Group (one Officer; Major Howard P. Serell, was already flown in on Christmas Eve in a light liaison plane –ed). After a half-hour flight, they landed by mistake in no-man’s-land among bursting shells. The sudden arrival of a friendly glider (pilot Charlton W. Corwin, Jr. and co-pilot Benjamin F. Costantino) drew small-arms fire as well. The medical team ran from the glider to the American lines, and when the firing subsided a bit, they returned to the glider to unload their medical supplies. Another hour passed before a truck arrived to carry the men and supplies into Bastogne, where there were hundreds of wounded men who could not be evacuated due to the enemy’s presence, including 150 seriously wounded, with only 4 already exhausted Doctors. Upon arriving in town, the team immediately went to work. Operation “Repulse” (run by the 444th Troop Carrier Group –ed) covered resupply flights into the encircled city of Bastogne between December 23 and 26, 1944, bringing in gasoline, ammunition, and medical supplies.

Two WC-54 3/4-ton ambulances on standby in front of a Clearing Station in the region of Metz, Lorraine, France.

The first 90 minutes were spent triaging the patients, followed by 18 hours of surgery, including many amputations made necessary by the delay in treatment. The volunteers, assisted by three Belgian women, and a 10th Armored Division Battalion Surgeon, operated all through the night and until noon of December 27, trying to fix wounds that had gone from 2 to as many as 8 days without surgical attention. Later the same day (December 26) US troops broke the German ring around Bastogne and ambulances arrived to remove the casualties and bring in more supplies. After a break, surgery resumed in shifts for another 24 hours during which a total of 63 operations were performed. When a German bomb knocked out the lamp in the makeshift hospital, operations continued by flashlight. Overall, the glider team did 50 major surgeries, and an uncounted number of minor ones, on men who had lain untreated for days, and lost only three patients. For these efforts, all the men of the 12th Evacuation Hospital (including the volunteers pertaining to the 4th Aux Surg Gp) who went into Bastogne were awarded the Silver Star “for conspicuous gallantry in action”.

Early on December 27, 1944, the first evacuation convoy of 22 ambulances and 10 trucks rolled out of Bastogne carrying 260 patients. Men of the 635th Medical Clearing Company unloaded the casualties, tagged them, and transferred them to 64th Medical Group ambulances for movement to Evacuation Hospitals. The vehicles from Bastogne then went back to the city for another load. In two days the medical units evacuated all of the 964 patients in the Bastogne hospitals.

In all of 1944, the 12th Evacuation Hospital admitted 18,707 patients; of which 15,517 in France. The 12th performed 5,506 surgeries and only 74 patients died. The rest of the 12th either remained at Nancy, France, until the first week of January 1945 or were sent on DS to hospitals situated closer to the front. More hospitals were needed close to the front lines as the Battle of the Bulge continued and counterattacking Allied troops faced stiff German resistance. The 12th sent scouting parties to Luxembourg City, where two sites proved inadequate, and the small spa town of Mondorf-les-Bains, only 18 miles from Luxembourg City, which was still under mortar fire and also unsuitable (in 1945, the Mondorf “Palace Hotel” eventually became “Camp Ashcan”, a kind of PW enclosure for senior Nazi dignitaries awaiting trial at Nürnberg –ed). On January 8, the 12th had to leave Nancy when the 2d General Hospital arrived to take over the facility and patients. With no new location yet selected, Colonel M. S. Brown led another scouting party toward the front. He found the “Caserne des Volontaires” in Luxembourg City which consisted of four large buildings plus some small ones, but it was already crowded with American units, Luxembourg police, the Headquarters of the Luxembourg Army (then reforming to fight the Germans), and refugees who had fled the recent German offensive. Colonel Brown apparently pulled rank, and the 12th took possession of the buildings, and everyone else (including Prince Jean of Luxembourg) had to find other quarters in the freezing winter weather. The change-over took only 4 days, but the 12th had time to adapt the buildings to hospital use. Hay and trash were cleared from the stables, which became the Enlisted Mess Hall, and a huge attic was converted into the Receiving Section, Operating Room, and Central Supply store. Because the buildings were built on the side of a steep hill and were more vertical than horizontal, special attention was paid to minimizing the number of times patients had to be carried up and down the stairs. By January 15, 1945, the Hospital was receiving patients while continuing to set up more wards. The same day, 97 patients arrived, followed by 187 the next day, 157 on January 17 and 213 on January 18, nearly filling the Hospital Plant in only 4 days. Continued heavy fighting kept admissions high for several more weeks. Staff members detached during the move to Luxembourg City returned to help as operations were stepped up.

Gradually the 12th Evac made improvements to the facilities, adding wiring and an internal telephone system, coal-fired stoves, and a snack bar offering hot soup and coffee. Twelve-hour shifts were the norm due to the large number of patients, and the 12th was therefore temporarily augmented with surgical teams, litter platoons, and ambulances. Surgeons performed operations while litter teams moved patients around the Hospital (the 12th was authorized only 38 men to transport the 700-plus patients), and the ambulances took stable patients 25 miles back to Thionville, France, to be loaded onto trains or airplanes for evacuation to other hospitals in the rear. The organization also hired civilian workers (largely for kitchen work, cleaning, and repairs) and even brought in some political prisoners for labor duty (Luxembourg collaborators). One civilian worker was killed when a German rocket hit the EM’s quarters. Because of extensive combat taking place during a bitterly cold winter, all hospitals were seeing a new category of patients: trench foot cases, caused by constricted circulation in the feet. The main cause of trench foot was cold, exacerbated by moisture; leaky standard shoes and inability to deliver dry socks to men on the front pushed the problem to alarming levels. After only a few days in the line, men might become unable to walk. The only treatment for trench foot was staying off one’s feet and allowing the body to heal on its own, so patients could be hospitalized for weeks, often suffering permanent damage. Trench foot had been a problem in Italy during the winter of 1943–1944, but the medical plans for the invasion of France paid little attention to the problem. The supply situation in France made the problem worse: winter clothing was deliberately given a low priority in September and October because there was still a chance of winning the war quickly. By the time warm clothes and appropriate shoes were put into the pipeline, it was too late, and some supplies did not arrive until warmer weather, when the problems had already passed.

December 26, 1944. Loading CG-4A glider at the A-82 airstrip, Etain, France in preparation for the flight to besieged Bastogne, Belgium. Interior view of the glider showing some medical supplies and equipment for the relief flight.

In February 1945 the 12th’s radiologist, Captain Charles Huntington, one of the few board-certified radiologists in the Army (the American Board of Radiology had been formed in 1934) began performing radiation therapy, then used for a variety of treatments including plantar warts on the foot. Previously, radiation therapy patients were evacuated to General Hospitals in the rear areas, sometimes even as far back as England, which meant they frequently joined Replacement Depots to fill the next vacancy rather than returning to duty to their previous units. This unpopular policy broke up teams and undermined camaraderie. The request to let Captain C. Huntington perform radiation therapy went all the way up to the Chief Surgeon of the European Theater, but was finally approved. The new policy offered the possibility of returning patients to duty sooner, with less disruption to the soldier and the unit.

The 12th Evac Hosp spent 2 months in Luxembourg City. Personnel had some recreational opportunities with passes being made available to visit Paris, and some long-serving Enlisted personnel men returned to the Zone of Interior (quotas had been introduced –ed). Some of these men had been in the Army well before the Lenox Hill contingent was mobilized and had attained a certain age, to be rotated home.

On March 9, 1945, the 12th Evac held a formation, during which the Third United States Army Surgeon presented the organization with the “Meritorious Service Unit Plaque” for their outstanding work between September 1 and November 30, 1944, during the advance across France and the fighting at the Siegfried Line.

Photo of the 4 members of the 12th Evacuation Hospital showing the men after being awarded the Silver Star. From L to R: Colonel Marshall S. Brown, Jr., CO 12th Evacuation Hospital; Captain Edward N. Zinschlag (General Surgeon), Captain Henry M. Hills (Orthopedic Surgeon), Technician 3d Grade John H. Donohue (Surgical Technician) and Technician 4th Grade Lawrence T. Rethwisch (Surgical Technician).

Germany:

By mid-March 1945, the Allied advance had regained momentum. The 12th Evac had been well located to handle casualties from the Battle of the Bulge, but now the Germans had been pushed about 37 miles further east, and Luxembourg City was no longer a useful location. It was time for the organization to move again, and Third Army authorities sent them to scout Trier, Germany. Engineer bulldozers had cleared only one narrow lane down the streets. The buildings allotted to the 12th had varying degrees of structural damage, including leaking roofs, and lacked water and electricity, but they were about the best available in Trier and, after a hundred German prisoners were assigned to help with the heavy labor, repair work started on March 18. Three days later the last convoy of personnel and equipment was unloaded. It had taken 144 truckloads plus some trailers and ambulances to move everything and everyone, including 80 Luxembourg civilian workers assigned to the unit for the rest of the war. After examining the stacks of equipment, especially furniture that had been made or acquired along the way and “household equipment” that made life more comfortable, the CO issued orders to get rid of most of it: only folding or nesting furniture could be kept. By late March, as German resistance was collapsing, Trier was already left too far behind the front. Only one day after the last truck had unloaded, word arrived from TUSA Headquarters to stop setting up the hospital. For the next week staff had little to do except enjoy the spring sunshine and play baseball in a vacant lot, but the war intruded when sniper fire broke up a baseball game. On March 28, Colonel M. S. Brown went to Frankfurt and selected a large sports stadium as the next operating site. A large advance party left Trier on April 2, followed by the rest of the unit as trucks became available (transportation was again a problem because Allied units advanced so fast that additional trucks were needed to supply the advancing units rather than move support units forward). Despite delays, the 12th Evac pitched its tents and was accepting patients April 5, 1945.

That month, although committed Nazis fought fiercely in some places, German resistance was patchy and few battle casualties arrived. However, because of the transportation shortage, few hospitals moved forward, and although it was located many miles in the rear, the 12th received patients straight from the front. There were more diseases and accidents than surgical cases, with respiratory and venereal diseases heading the list. Another category of patients began arriving: RAMPs, Allied PWs liberated from German prison camps. Some were British (including men who had been captured back in 1940) and some were American; the latter being a mix of bomber crews shot down over Germany, soldiers captured in the Battle of the Bulge, and even soldiers captured in North Africa as far back as 1942. All the former PWs received a check-up and washing, since many had parasitic diseases. Many were underweight, but few had diseases. As soon as they were medically cleared to travel they were sent to France with special flights, and eventually homeward by sea.

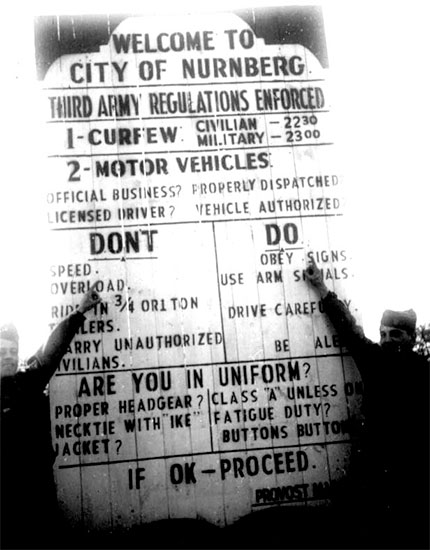

Germany 1945. Signpost detailing regulations enforced by Third United States Army (TUSA) authorities in the City of Nürnberg, Germany.

With few patients, the staff had time for leisure activities. A swimming pool in the stadium complex was filled and open for men from 0800 to 1700 hours (swimming suits were required only from 1300 to 1500, when the Nurses swam). Movies were regular, and baseball teams were organized for intra-unit and inter-unit games. As other hospitals began moving forward, the 12th received even fewer patients and some staff contended with boredom. V-E Day, and May 9, 1945, resulted in a brief spurt of injuries from celebratory vehicle accidents and accidental shootings. The men and women of the 12th, however, had seen enough of the human cost of war and, while thankful that Germany had surrendered, did little celebrating; instead they held both Protestant and Catholic memorial services to honor the dead.

Despite the end of the war in Europe, the 12th’s personnel remained in service. The Army had to decide who would be discharged, who would be transferred to the Pacific Theater for the anticipated invasion of Japan, and who would join the Occupation Forces in Germany. The key factors in this decision were physical profiles and the Adjusted Service Rating (ASR), a points system that calculated how long someone had served and how relatively grueling their time had been. Preparing paperwork for these ratings took only a few duty hours, and service members filled their time in the Army’s extensive new education and special service programs, including sports and cultural or sightseeing trips; however, these diversions failed to distract personnel from thinking about going home.

V-E Day and the End:

A few weeks after May 9, 1945, Third Army authorities again sent the 12th on the road, this time 138 miles to Reichelsdorfer Keller, a small town outside Nürnberg. By May 28 the organization had pitched tents for living areas (there was no more need for hospital wards or treatment areas), and as June began, personnel sunbathed, swam in the nearby river, enjoyed fishing or hunting, played sports, and performed a minimum of Army duties. Physical training was required, as were orientation lectures on how to behave in Germany, how the Army was handling the return from Europe, and other administrative topics. As a distraction, Colonel M. S. Brown arranged regular sightseeing trips, one into the Alps, one to Berchtesgaden (Hitler’s retreat, with villas of other high-ranking Nazis), and day trips to nearby medieval cities. On June 18, the organization learned that it had been selected as a category IV unit, meaning it was one of the hospitals scheduled for prompt return to the Zone of Interior and inactivation.

This decision was expected because most of the troops had originally been scheduled to go to the Pacific; the highpoint Enlisted Men would be exchanged for low-point soldiers from other units, and nobody was sure what would happen to the Officers and Nurses. Orders started trickling in, transferring new men in and experienced ones out, and temporarily attaching some of the clinical personnel to other hospitals to keep their skills fresh. In mid-July there was massive turn-over of the EM as high-pointers were transferred to the 34th and 104th Evacuation Hospitals in exchange for low-point men from those units. It took days to sort out the skills and experience of all the new personnel so they could be assigned to appropriate duty. Meanwhile, news arrived that the Medical Officers would be stripped out of the 12th before it went to the Pacific, to be replaced with a different group there. Adding to the general turmoil, a new Commander, Colonel George McCoy, arrived on July 20, 1945. The 12th Evac spent the following days sorting out administrative paperwork, checking and inventorying supplies and equipment, continuing the training program, assigning duties to the new Enlisted replacements, and reorganizing until the news arrived in mid-August that Japan had surrendered unconditionally!

Colonel George McCoy, Commanding Officer, 12th Evacuation Hospital, awards the Legion of Merit to Captain Lillian Carter, ANC Chief Nurse, July 29, 1945, during formation and parade, somewhere in Germany.

Commanding Officers – 12th Evacuation Hospital

Lieutenant Colonel Rawley Chambers

Lieutenant Colonel Otto Pickhart

Colonel Marshall S. Brown, Jr.

Colonel George McCoy

The 12th’s routine reports from the middle of 1945 have been lost, but records show that the unit shipped home from Europe to Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey, arriving late in 1945 or very early in 1946. Only a few individuals traveled back as members of the 12th Evacuation Hospital; most of the wartime 12th Evac had already been assigned to another unit or were sent home based on their personal ASR score. The 12th Evacuation Hospital was inactivated at Camp Kilmer on January 6, 1946, and formally reverted to the reserves.

During its stay in England, the 12th Evacuation Hospital treated about 8,000 patients, and another 26,000 in France, Luxembourg, and Germany.

Despite being on the receiving end of German shells at Nancy and buzz-bombs at Luxembourg City, despite the risks of riding landing ships to the Normandy beaches and a glider into Bastogne, only 2 personnel from the 12th Evac died in World War II. Both were ANC Officers: 2d Lieutenant Harriet Beckman died on October 25, 1943, in an automobile accident, and 1st Lieutenant Louyse Bosworth died as result of a fall in Luxembourg on February 15, 1945.

Special Award – 12th Evacuation Hospital

Meritorious Service Unit Plaque > awarded March 9, 1945

This concise Unit History was initially edited based on material contained in World War Two vintage reports related to the 12th Evacuation Hospital’s operations between August 1942 and 1945 in the European Theater, as well as on extra documents produced by AMEDD for which the MRC Staff are very grateful. While reviewing the documents, some important data and general information were added by the MRC Staff. We are still looking for a complete Personnel Roster of the Hospital and would like to learn more about the organization’s return to the ZI at the end of the war. Thank you.