44th Evacuation Hospital Unit History

Partial view illustrating some of the wooden buildings, at Cp. Atterbury, Columbus, Indiana (old postcard).

Activation & Training:

On 29 August 1942, a cadre of 37 Enlisted Men, commanded by 2d Lieutenant Martin H. Fisher, QMC, O-1577167, from the 15th Evacuation Hospital, Ft. George G. Meade, Baltimore, Maryland (AGF Replacement Center -ed), reported for duty at Camp Atterbury, Columbus, Indiana (Division Training Camp -ed), and the “Forty-Fourth” became an activated reality on the following day.

On 16 September 1942, Lt. Colonel Elmer A. LODMELL, MC, O-19315, joined the unit and assumed command. At that time the fledgling unit consisted of a mere 7 Officers and 40 Enlisted Men. Lt. Colonel William S. PARKER became the unit’s Executive Officer.

Like most normal infants its first few months saw a rapid growth. Men began to pour in; 134 arrived on 11 October 1942 from the Reception Center, Ft. Niagara, Youngstown, New York (ASF Training Center -ed). Other acquisitions included 61 men from the MRTC, Cp. Barkeley, Abilene, Texas, who arrived on 18 November. Another 45 came from the IRTC, Cp. Joseph T. Robinson, Little Rock, Arkansas, on 23 November. Others joined singly or in small groups during fall and early winter, so that the 44th Evacuation Hospital entered 1943 well over strength as far as EM were concerned. The official T/O called for 217 Enlisted, 40 Nurses, and 39 Officers! During fall and winter, more MC and MAC Officers put in their appearance.

Life at Cp. Atterbury could be divided into 2 periods: Basic Training and Unit Training. After these special introductory experiences came to an end the Hospital unit passed the Mobilization Training Tests, conducted under Second United States Army Headquarters on 27 January 1943, with flying colors, being rated as the best of the three Evacuation Hospitals examined there! As a result of this outstanding achievement, the 44th was allowed to proceed with the Unit Training Period immediately.

General view illustrating post D-Day activities at one of the sectors of Omaha Beach, France.

The Training was to continue for 11 weeks until start of the Tennessee Maneuvers. Emphasis was laid upon the functioning of the Hospital as an integrated unit. Long and unpleasant memories will remain such as the “Bitter Bivouac”, when temperature fell to 5 degrees sub-zero and men slept in pup tents on the frozen ground. It was during this same period that a large number of men went to various Technical Schools – Surgical, Medical, X-Ray, Dental and others. Most classes were given at Billings General Hospital, Ft. Benjamin Harrison, in Indianapolis. Officers were sent to “Dear Old Carlisle”. The Tennessee Maneuvers began about 20 April and continued up to 26 June 1943; they began with the dramatic arrival of Captains Allan K. Swersie, Zemke, Liotta, and Barryte, clad in “Greens and Pinks” and with all the paraphernalia of newly-commissioned Garrison Officers just as the rugged field soldiers of the 44th Evac Hosp were about to pull out for the hills of Tennessee on board of 2 ½ trucks…

It became a history-making period in the life of the 44th, when the unit actually began to execute things previously learned in theory. It was a period of sitting around with mess kits, trying to get more food than the flies and insects; a time of floods when individual tents and ward tents were well-nigh washed away; a time of pitching and knocking down tentage; of swift and sudden moves by day and by night; of receiving the first patients, of the mangled victims of a bomber crash; of the first operation …

It was a memorable thrill to see the first parachute drop of the 101st Airborne and their aircraft and gliders circling over the Hospital, but it was something else to receive 185 casualties from that drop within a 24-hour period and to take care of them properly. Suddenly everyone realized that this was more than just ‘playing’ at war! It was then that the 44th Evacuation Hospital received its first General Officer patient – General William H. Lee (Father of the Airborne), who was injured in a glider crash. Eight different functioning setups were established during the Maneuver period, and while at rest near Scottsville, Kentucky, the first Nurses joined the unit. 20 American girls, from Ft. Jackson Hospital and Starke General Hospital were welcomed as well as the 2 first American Red Cross workers.

It was a wiser outfit that made its way northward on 26 June following the Tennessee experience – over 1,700 patients had passed through the wards. Approximately another month was spent at Cp. Atterbury, the home station and during this period 20 more Nurses, 10 from Ft. Benning, and 10 from Lawson General Hospital put in their appearance. 1st Lieutenant Martha E. NASH had meanwhile been appointed Chief Nurse of the 44th Evac.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

After a month at Cp. Atterbury, the large ‘deuce’ of the Second United States Army SSI was removed and the green clover leaf and red triangle of the XIII Corps became the current shoulder insignia. After this change came a truck trip from Atterbury to the wilds of West Virginia, entailing bivouacs in Ohio and W. Virginia enroute to Elkins (final destination > Stuart Park -ed). This period lasted from 28 July to 22 September 1943 with the 44th Evacuation Hospital acting as a Base Camp Hospital, thus essentially a Station Hospital, for the West Virginia Maneuver Area. Work however continued, and a considerable number of accident cases came in, including a certain number from the Mountain-climbing School at Seneca Rocks. Orders for movement finally came on 22 September, and the unit then transferred to Ft. Dix, Wrightstown, New Jersey (Training & Pre-Staging Area -ed). All the old equipment, in fact the entire installation was turned over to the 27th Evacuation Hospital, a 750-bed outfit, as the 44th departed by truck for the Elkins Railway Station. After arrival the men were led to a section of the tent camp city where new equipment was issued and checked. Inspections, training lectures, and films were attended. Replacements also came in. Weekend passes and furloughs were granted, and everyone realized the unit would soon be traveling overseas. On 10 November 1943, the 44th Evacuation Hospital was ordered to proceed to Cp. Kilmer (Staging Area, New York P/E -ed) for final preparation of overseas movement!

The evening of 16 November, the Hospital entrained for the NYPOE where an advance party had already arrived. There was the long wait on the cold docks by the ferry in Hoboken, and the long hike burdened with duffel bags, packs, and musettes up to the ship. For many it was the first glimpse of a transatlantic liner. After being called, the men then strode or staggered up the gangplank of the “Aquitania” (sister ship of the “Mauritania” and “Lusitania” of WW1 fame, and requisitioned in fall of 1939 for troop transport duty -ed). Military personnel from other units were located deep in the hull on E and F decks below the waterline, but the Hospital personnel were more fortunate, since everyone was located on triple rows of bunks on the decks behind temporary shelters, cold maybe, but invigorating, and at least with the possibility to breathe fresh air.

Arrival in the ETO:

Life on the S/S “Aquitania” was naturally cramped with over 8,000 aboard, of various types and nations (Americans, Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders). Meals were served twice a day and the lines again were very long. Safety drills were held and a limited number of shows were worked out, moving from deck to deck nightly. Frequently one could hear the humming of an engine, and when men rushed to deck, they found out it was a Flying Boat guarding our passage. There was no convoy for the ship was too fast for a convoy. Rumors about enemy submarines flew thick and fast as the ship changed direction, but nothing actually developed.

Surgeons of the 44th Evac Hosp at work in one of the operating wards. France 1944.

The weather was excellent most of the time, but towards the end of the crossing, it grew a little stormy and the ship pitched and tossed. During the night the “Aquitania” gently moved up to the mouth of the River Clyde and dropped anchor off Gourock, north of Glasgow, Scotland. The ship was now nearby the “Queen Mary”, and a little further lay the “Queen Elizabeth”. The wait was long but around noon the unit debarked to a loader which made its way slowly to the dock where another interminable delay took place in the penetrating cold of a Glasgow afternoon. A loudspeaker played the haunting strains of Bing Crosby, the Red Cross provided coffee, doughnuts, and apples, and when driving through Glasgow, everyone waved, cheered and greeted the Americans enthusiastically. Then it went straight through the night by train, with only one stop for coffee and sandwiches, until the train pulled into the Maidenhead Station, Berkshire, on Thanksgiving Day – it was 26 November 1943.

England:

The ‘Battle of Maidenhead’ (England) began with a prayer of Thanksgiving and a dinner of stew. In spite of the stew, the prayer was genuine, it was held in the old carriage house, reverse Lend-Lease, used as a Mess hall. But security soon began to blend into monotony, Thanksgiving was translated into gripes, and the Battle of Maidenhead, a six and a half siege of ennui and boredom, was on in earnest! The pea soup fog for which nearby London was justly infamous for began to settle down, and the weather while nothing like the cold of American winters, was far more damp and penetrating, resulting in a number of personnel spending a day or two in a nearby Station Hospital with nasopharyngitis. The billets were far apart and walking through a blackout with shaded torches was semi-suicidal.

Maidenhead was an attractive town with friendly people. Members of the unit were billeted with reasonable comfort, however the tiny English fireplaces and lack of central heating produced comments not exactly favorable to the customs of the “blasted little island”. The Officers were quartered in Avening, Norfolk House, Thames House and elsewhere, while among EM the billets were Crawford, Ray Mill Lodge, and The Pavilion.

Training was always present, unit classes continued throughout this period and numbers of personnel went to various Schools on detached service – members of the 128th Evacuation Hospital which had seen heavy duty in Africa visited the 44th and imparted the wisdom of their combat experience. Aircraft identification, bombs, gas, as well as various technical medical subjects were studied.

Many marches were arranged for to the places nearby, located in the midst of an historic and charming countryside. But all was not fun, field exercises were constantly taking place, and on 2 January 1944 the Hospital unit moved out for its first encampment in England, near Bray. There were no stoves, the weather was damp and penetrating. Then the Hospital was inspected by Brigadier General John A. Rogers, MC (CO > First United States Army Medical Section) and Brigadier General Paul R. Hawley, MC (Chief Surgeon, ETOUSA).

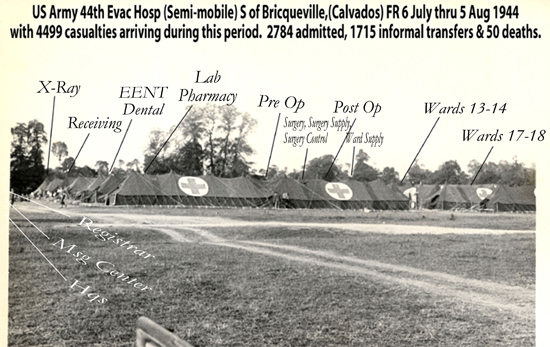

Partial view of the 44th Evacuation Hospital in France. Picture courtesy Robert L. Robinson.

The greatest transition ever experienced as a unit came on 21 February 1944, when Lt. Colonel Elmer A. Lodmell, who had commanded and trained the unit from its early days was transferred to command the 3d Surgical Auxiliary Group, while the unit’s CO, Colonel John F. BLATT now assumed command of the 44th Evacuation Hospital. A number of other personnel changes were made at the same time and this called for a farewell party that was held at Skindles Hotel. The new CO took over with informality and easy efficiency, and always paid attention to the personal comfort and the convenience of personnel. During the winter months, parties enlivened things, numerous dances were held, the Sergeants opened up a Club, and many passes were issued for visits to London, Stratford-on-Avon, Oxford, Bristol, Reading and other famous cities. As spring came on, the Thames River grew more and more popular. In mid-winter the unit was enlivened by the coming of Misses Catherine Wilson and Mary Mahar of the American Red Cross. The Chaplain, Captain David B. WALTHALL, Jr. maintained regular Protestant services in the Methodist Chapel at Maidenhead, while Catholic personnel attended religious services at St. Joseph’s. The outstanding religious service of that period was the one held at Cliveden, home of Virginia-born Lady Nancy Astor, and Lady Astor spoke to the groups present as a feature of the service.

On 18 April, the Quartermaster Laundry Section (CO > Lt. John A. Hatherley) was attached to the 44th and the Commander and his 33 men soon became an integral part of the outfit.

The war went on, and sight and sounds of it became not too far distant with British searchlights combing the skies for enemy aircraft, and frequent alerts with sirens and ack-ack fire. In addition to this, pleasant but casual friendships formed by many, became serious, and in spite of all the red tape, persevered to the altar. 6 marriages took place between Aril and May. As spring broke through, the unit set up near Cookam on property of the Courtauld Textile Company for field exercises. This arrangement which had started in March continued in April and May culminating with a large field exercise with First US Army’s 68th Medical Group (CO > Colonel Francis P. Kintz, MC), during which 150 simulated casualties were tagged, transported to, received and registered, passed through pre-op to surgery to post-op and evacuation. The unit worked smoothly during these tests and was obviously ready for its next period, that of actual operation in a combat zone!

First Operation in the ETO:

News of D-Day and the Normandy Beachhead had come in and as the unit had been alerted for some time, a guarded announcement was made at 121930 June 1944 that “time has come” – the Hospital soon learned that it was to leave early on 13 June for Cp. Hursley in the Southampton area. A party consisting of 35 Officers, 40 Nurses, 2 Red Cross workers, and 193 Enlisted Men, left by rail, unloaded at Winchester, and proceeded by truck to Cp. Hursley. The same evening, the vehicle party including 4 Officers and 58 EM arrived with 56 vehicles too. It left again on 15 June under command of 1st Lieutenant Raymond Gilewicz for the cross-Channel lift and was not seen again before reaching Normandy. Life at Cp. Hursley was strained while everyone was anxiously awaiting the announcement that unit “Q544T” was to prepare to move. Then the rugged 83d Infantry Division moved into the area. After a false alarm a couple of days before, the unit received movement orders at 0355 18 June and at 0730 the group left by motor convoy for Southampton.

The same afternoon, it was 1700 hours, the unit embarked on 2 LCIs and anchors were weighed at 2000 hours. After rendezvousing with a convoy off Portsmouth, the convoy left at 2300 with destination the beaches of France. On arrival at the landing beach, designated Omaha, at about noon of 19 June, waves had become rollers blown by a strong wind and the makeshift harbor was crowded with vessels, and it was next to impossible to land on the beach itself! The pitching of the craft had been almost unendurable until they passed through the breakwater of concrete-laden ships. Inside there was still considerable chop but the cases of seasickness began to improve and soon many were able to enjoy the self-heating cans of split pea soup which had been issued. However there was much more confusion in the harbor during the afternoon, with boats losing their anchors, cruising about in an effort to tie up to some more fortunate vessel. The LCI with most Officers and Nurses aboard lost anchors three times, the other landing craft which carried most of the EMs pulled a half-drowned man aboard who had been lost off a ”dukw” (2 ½-ton amphibian truck -ed) and administered first-aid. Overhead, a hundred or more barrage balloons added their weirdness to the scene, and the whole beach was covered with wrecked ships, barges and landing craft of all varieties and shapes. The LCI loaded with the Enlisted personnel managed to get fairly close to the beach to let down its ramp, allowing the men to wade ashore with full pack in the knee-deep surf. There they assembled on Dog Red and proceeded to the nearby transit area under command of 1st Lieutenant Stanley J. Waxman. Pup tents were put up in a small apple orchard surrounded by hedgerows and since many foxholes had been dug by the preceding Infantry, the men were glad to take advantage of them in case the krauts took over the night skies and friendly AAA-fire began to roar. This took place in the latter part of the afternoon of 19 June. The LCI with Officers and Nurses succeeded at 1900 to tie up to a Mulberry and disembarked its human load. The men soon moved 8 miles inland to La Cambe and spent the night there with the already set up 45th Evacuation Hospital. The next morning, 20 June 1944, the whole unit gathered there and immediately proceeded to set up its first installation on French soil, 1 ½ miles west of La Cambe on the Bayeux-Carentan-Cherbourg highway, opposite the recently opened 29th Infantry Division field cemetery…

France:

This same day saw the FIRST battle casualties at La Cambe. This installation lasted from 20 June to 6 July and was splendidly adapted to breaking the Hospital into its progressively greater task. Here 459 patients were received from the 29th and 30th Infantry Divisions, the 2d Armored Division, and other XIX Corps units. During this period there was only a single death at the Hospital. However, the presence of the cemetery right across the road was an ever present reminder that there was a war on, indeed, the whole area was packed with troops and the highway was a continuous stream of armored and other types of vehicles. One day a 90-mm antiaircraft battery was installed in the next field, and this certainly did not make for comfort. Patients were meanwhile received in alternation with the nearby 45th Evacuation Hospital and the 24th Evacuation Hospital not far away either. Quite a number of self-inflicted wounds were received too. During the same period a detail of the 44th was sent to help clean up after the capture of Cherbourg, and many returned triumphantly with captured war trophies.

The La Cambe Hospital area closed and orders were received to move to Bricqueville, again in support of XIX Corps, from 6 July to 5 August, and meanwhile the 44th Evac Hosp learned the hard way what war was like. It was during this period that the unit received extremely heavy casualties from the Battle of St.-Lô. At times double ward tents had to be erected in order to handle all the wounded, some days over 500 casualties were admitted and the strain on Officers, Nurses and EM was tremendous. Sometimes the surgical backlog amounted to over 300 cases, as a result 8 operating tables worked day and night. More help was needed and received in the form of surgical teams from the 3d Auxiliary Surgical Group. 50 German PWs were assigned for help in housekeeping. Patients received were largely from the 29th and 30th Infantry Divisions, and the 3d Armored Division – 4499 patients passed through the Hospital, 2748 of which were admitted as patients and the rest informal transfers. There were 50 deaths. The unit performed admirably and by the time St.-Lô was captured, the Hospital functioned like the veteran it had become! Many memories cluster around the Bricqueville area, such as the acquaintance with a beverage called ‘calvados’, the gallant fight for life put up by some patients, the unfortunate loss of limbs, the award of Purple Hearts to some wounded who were strafed and killed when returning to a Replacement Depot… it was at this time that the unit came to know Chaplain H. J. Palmer. The unit had no Catholic Chaplain and so he attached himself to the 44th for extra duty. He would serve his own Ordnance unit by day and in the afternoon, when the wounded began to pour in, he would come over and work in the wards till the late hours, then snatching a few hours of sleep on a cot, he would be up again by dawn and on to his own unit. When the Hospital closed for a few days of rest, the Chaplain would go to another medical unit which was receiving patients.

Time for some rest and relaxation. Nurses of the 44th Evac Hosp enjoy a short rest.

Towards the end of the stay at Bricqueville, patients reported that the big Allied breakthrough was about to occur, and without rest the outfit moved to Percy on 6 August passing through St-Lô (where the 77th Evac would open on 9 August). This movement constituted something of a record, leaving its former location and traveling some 40 miles to Percy, south of St.-Lô, the Hospital was erected and began receiving casualties within 8 hours! The engineers had not finished sweeping the fields for mines when the tents were pitched! The 44th Evac again supported XIX Corps in its defense against severe German counter-attacks at Mortain, and subsequently headed for the Argentan-Falaise pocket which was beginning to develop. A special mobile OR for treating minor wounds was set up under Captain Allan K. Swersie. Altogether there were 1266 patients and 25 deaths during the period lasting 12 days and closing 17 August. When the breakthrough took place tremendous strain was thrown on transportation. To help meet the crisis all evacuation motor pools were joined in a First Army Medical Transportation Pool – the unit’s vehicles were so included and for days and weeks crews worked indefatigably and interminably, only returning to the unit once a week for clothes and equipment. By this time the Allied breakthrough had gone forward in a magnificent way and the Hospitals found themselves outstripped by the advancing armor. On 18 August the 44th Evacuation Hospital advanced to Domfront, luckily the work got lighter and only 283 cases came in, with only 1 death from complications. In total 109 operations were performed by the surgical teams. (Between 1 August – 12 September 1944, First United States Army Hospitals admitted over 19,000 wounded, not counting sick and injured -ed).

The latter part of the stay became almost a holiday for everybody. Some hung out on the river banks, others journeyed to Bagnoles for relaxation. Some spent their time trading their candy and cigarettes for fresh eggs and salads from the neighboring farmers. But most memorable were the trips to Mont St. Michel. Ambulances from the units which then served us were borrowed for the trips. From Omaha Beach to Domfront, the “Forty Fourth” had been served by the 463d, the 493d, and the 564th Medical Collecting Companies, whose personnel had lived in adjoining areas and with whom the 44th baseball team had played against when time could be found…

As the Germans were being rapidly pursued through France to the shelter of their ‘Siegfried Line’, little use was found for Evacuation installations. Therefore on 29 August the unit left Domfront to a concentration area of the 68th Medical Group at Senonches, in company of a number of Hospitals and other medical units (between 25 – 31 August 1944, Hospitals, Depot Companies, and other medical units were grouped there, 50 miles southeast of the French Capital, on the line of evacuation from the advancing infantry and armor to the beaches -ed). There was now some time for rest and recreation. Paris had been freed, and practically every member of the unit got there. GIs with their cigarettes were besought by Frenchmen everywhere, the Black Market had begun, and precious fags went for enormous sums of French Francs! Others took time to visit the City, the Notre-Dame Cathedral, the Eiffel Tower, the Tomb of Napoleon, and all the rest. Trade with the French farmers flourished and everyone enjoyed the fresh foods obtained. Friendships were begun with the local village folk and the whole period was one of much needed relaxation.

Belgium:

First Army again needed the Hospital. On 11 September 1944 the unit moved rapidly along the wreck-strewn roads of France to La Capelle near the Belgian border where it bivouacked for one night. Passing through Soissons and finally crossing the Franco-Belgian border in the vicinity of Bouillon, where some Belgian girls were having their heads shaved by the Résistance for having fraternized with the Germans, the unit encamped on the night of 12 September in the beautiful forest of St. Hubert.

Operations here lasted from 13 – 26 September and proved to be exceptionally and surprisingly heavy. V Corps was now being supported by the 44th and 2508 patients were received, mainly casualties from the 4th and 28th Infantry Divisions and the 5th Armored Division. Here the Hospital was placed the farthest forward in the Corps area and set the record of receiving 519 admissions in a 24-hour period! There were 17 deaths. Four ward tents were put up together so that the resulting floorspace could accommodate around a 100 cots. This was in part necessitated by the terrific amount of rain and mud with which personnel had to contend. Wheels of ambulances and trucks literally sank knee-deep in the mud; moreover, the temperature started to lower, requiring the use of tent stoves. The Belgians gave the unit a royal welcome and from time to time brought much appreciated gifts, such as fresh eggs, for the wounded. As war moved on, the 44th was on the move again and advanced towards Malmédy. On 26 September the Hospital moved into the local school building on the southeast edge of town – this was the FIRST time on the continent, that the Hospital set up in a building. Quarters were most comfortable, and the Nurses moved into handsome residences vacated by Nazi sympathizers who had fled to Germany, while the Officers took over the Customs building, and the Enlisted Men were happily housed in private dwellings and former barracks. The front had stabilized and there was time for a little relaxation in clubs which were quickly getting organized. The 67th Evacuation Hospital was installed nearby and shared what patients there were.

From 16 November on, the frontlines to the north of V Corps, i.e. the Huertgen Forest, became heavily involved in battle and consequently the tempo picked up. During this period there were 5595 admissions and 20 deaths. Many admissions were suffering from ‘trenchfoot’.

Among some of the outstanding entertainment events was the “world premiere” of ‘Saratoga Trunk’, which took place in the First Army Theater in Malmédy. Various USO and Special Services shows helped to pass the time, baseball stars visited the place, and people like Mel Ott, Bucky Walters, and others drew big crowds. ‘Thanksgiving’ was properly celebrated with a big religious service for all units stationed in and around Malmédy, and an appropriate Thanksgiving dinner with turkey was served. Shortly before all this, the infamous “buzz bombs” made their appearance, usually passing safely over the unit’s heads enroute to Liège.

During the early December 1944 days, the number of casualties increased considerably. The 106th Infantry Division, fresh from the States, had been put into an overextended line on the front 15 miles to the east, while the more experienced Infantry units were drawn off for the projected push against the Roer River defenses. A bit further south was the 28th Infantry, badly punished in the Huertgen Forest, which had been given a quiet place in the line. A number of Divisions were covering an overstretched main line of resistance in forest-covered hills and valleys… On Saturday, 16 December 1944, the 44th Evac’s greatest adventure began with the shelling of Malmédy by a heavy German railway gun, as early as 0545 a.m. The obvious purpose was to disrupt communications and traffic but the engineers soon had the roads open again. One shell however exploded at the door of a Belgian Catholic church, perhaps 50 yards from the Hospital, where a number of civilians were killed or wounded as they emerged from morning Mass. Altogether 11 civilians were killed and 3 Americans (1 Captain and 1 Enlisted Man from a nearby medical unit, and another GI from the Replacement Depot). The wounded civilians were immediately admitted to the Hospital where, despite every possible attention, a considerable number later died from wounds. The 44th was unaware that anything unusual was happening until the next day – during the night of 16 – 17 December, the XO was informed that German parachutists were being dropped in the area between Eupen and Malmédy. Tension then mounted steadily until the Motor Pool was ordered around noon of Sunday, 17 December, to evacuate a Platoon of a Field Hospital some distance in advance of us at Waimes, which was right in the path of the advancing enemy. All but 1 truck, driven by T/5 Donald Pickard, which started behind the others, reached the Hospital safely and loaded all personnel and equipment. Then a small German unit suddenly appeared, captured the drivers, along with the remaining 47th Field Hospital personnel, and were about to drive them off when an American half-track put in its appearance and quickly drove the Germans from the scene. The men had been prisoners for perhaps 45 minutes and were grateful for a timely rescue! Not until much later was the fate of Don Pickard discovered and for a period of perhaps a month he was reported as “missing in action”. Some distance out of Malmédy and enroute to Waimes, he evidently came under enemy artillery fire, perhaps he got wounded or perhaps he turned off the main road to avoid it, just off a small forest road southeast of Malmédy his body was found, shot through the chest. Pfc Joe Chavez was also reported missing for several weeks but later turned up.

Litter party on its way in the field. Trying to save another ‘precious’ life …

Sunday afternoon, 17 December, the unit was informed of the German attack and breakthrough, and told to evacuate! Many had heard the rattle of gunfire on the outskirts of town which may well have been the horrible massacre which occurred at the Baugnez crossroads (involving personnel from the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion). Among the surrendering Americans, mowed down by enemy machinegun fire in cold blood, was Lieutenant Carl Ginthner (575th Motor Ambulance Company) who had served with a Medical Collecting Company bringing patients to the 44th Evacuation Hospital. During the earlier part of the day he had been wounded slightly and treated at the Hospital. Stating that the wounded had to be gotten out he went back to do his job and got killed. A few, perhaps 5, of those executed escaped, and 1 or 2 of them were later attended by members of the 44th Evac medical staff. During the early afternoon the Hospital continued to receive incoming patients, with the enemy only 3 miles away. At 1400, when verbal orders were received to evacuate, there were still 175 patients in the wards. Lt. Colonel William S. Parker; Major Donald G. Penterman; Captains Leo Lefkowitz, Ivan C. Dimmick, and Peter B. Kaminsky, and Enlisted Men Brown, Fletcher D. Arrington, Gerald A. Fiegl, Cruz V. Hernandez, Armond Magliocco, Lowell T. Bybee, Alfred T. Smith and Cleveland E. Hayward volunteered to stay in Malmédy with the remaining patients. Only 2 trucks remained as the others had not yet returned. These had been loaded with Nurses and sent to the 4th Convalescent Hospital at Spa. Other personnel started walking, eventually more ambulances and miscellaneous trucks were obtained from the Surgeon’s Office and under the direction of Lt. Colonel Wm S. Parker, Major Donald G. Penterman, Captain Stanley J. Waxman, F/Sgt Dominick L. Garcia, and T/Sgt Crawford, ALL remaining patients and personnel were assembled and evacuated, and all equipment was abandoned. The unit then reassembled at Spa that same night. Other medical units, such as the 67th Evacuation Hospital, the 618th Medical Clearing Company, and the 2d Advance Section, 1st Medical Depot Company hastily retreated to Spa. The night of 18 December, under cover of darkness, another rear movement was made, largely in the unit’s recaptured motor vehicles to Huy. Bedding rolls and sleeping bags were spread on benches and floors of the Couvent Ste-Marie and the unit rested.

Because of the necessity of immediate evacuation, there being no more vehicles available, the unit had left all of its hospital equipment and most of its personal gear, except what could be carried on one’s back or by hand, in Malmédy! As the Germans never actually captured the town, the equipment was not captured by the enemy but was pillaged considerably by civilians. After a few days, it was found that there was still a road open into Malmédy and considerable portions of medical items were salvaged. It proved impossible though to get the Hospital back in working order for some time, which was spent in Huy. While in Malmédy the 44th recorded 5595 admissions, of which 1173 surgical cases. Total admissions on the continent sofar were 12,895. (First US Army Hospitals admitted over 78,000 patients, 24,000 of them wounded, between 16 December 1944 – 22 February 1945).

From the hasty withdrawal on the night of 18 December until 23 January the unit remained in Huy in comfortable although rather crowded quarters. Sister Anne of the Convent and the other Nuns did all in their power to make everyone feel at home. A very festive Christmas dinner was served and several shows and a dance or two helped relieve the monotony. Many people went on detached service in Huy to help the overburdened 102d Evacuation Hospital and to the 45th Evacuation Hospital at Eupen (First US Army medical concentration area -ed). It was during the first week at Huy that the weather became cold and snowy, then clear again, but cold. More Bronze Star medals were awarded to Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted personnel by Brigadier General J. A. Rogers. The equipment which could be salvaged was stored at Dolhain, then moved to Huy where it was worked over. As the 102d Evacuation Hospital lost its CO, Colonel John F. BLATT was made temporary Commander of that unit also. Our staff put into effect the techniques that they had learned so well in the school of hard experience. The 102d adapted itself to the new deal, functioning most effectively with the 44th system of Admission and Evacuation established by Captain Blaine M. Anderson and others. At Huy, the Hospital again functioned under the 68th Medical Group. Colonel J. F. Blatt suffered a head injury due to a fall on the ice and was sent off to Paris for hospitalization. Lt. Colonel William S. PARKER, XO, assumed command of the unit, soon to be succeeded by a Colonel Crane, Medical Consultant from First United States Army Headquarters.

The 44th Evac Hosp was partially involved in processing the remains discovered after the “Malmédy Massacre” at Baugnez. It was not until 13 January 1945 (after the area had been retaken by troops of the 30th Inf Div -ed) that bodies were discovered in the fields around the crossroads. There was a conference with representatives of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion which detached a platoon with mine detectors. The snow was gradually melting, and details were organized to start recovering, processing and identifying the bodies. Litter bearers belonging to the 3200th Quartermaster Service Company (Colored) helped by personnel of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion were tasked with grouping the bodies and for bringing them to an abandoned railway building in Malmédy. Members of the 3060th Quartermaster Graves Registration Service Company’s Fourth Platoon would help with recovering and processing. Operations started 14 January 1945. US troops discovered quite a number of bodies including:

66 members – B Company, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion

3 members – Headquarters Battery, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion

4 members – Reconnaissance Troop, 32d Armored Regiment

2 members – 200th Field Artillery Battalion

2 members – 546th Motor Ambulance Company

4 members – 575th Motor Ambulance Company

1 member – 86th Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion

2 members – 197th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion (SP)

After transportation to Malmédy, a number of Medical Officers pertaining to the 44th Evacuation Hospital carried out autopsies of the bodies recovered. They were Major Giacento Morrone, Captain Joseph Kurcz, and Captain John Snyder. Findings concluded that a number of bodies had been mutilated by artillery fire during recapture of the area and by hungry animals, while a number of the prisoners had obviously been shot in the head and severely been wounded by hits received from rifle butts.

Another view of a surgical ward. Picture of the 44th Evac Hosp while set up in France, 1944.

By this time Supply had gotten the equipment back in operation and on 23 January 1945, orders were received to advance to Vielsalm, to the Pension Sacré-Coeur, to receive casualties from the approaching end of the Battle of the Bulge. Being in bad condition because of shelling, it took several days for Utilities to get the building into service condition. Opening on 1 February, the Hospital closed again on the 4th, operating only three full days and receiving 599 patients, with 131 passing through surgery. A long move was next in order and preparations to move into Germany were now planned.

Germany:

On 9 February the unit moved by truck to a large German Barracks at Brand, southeast of Aachen. Many of the men saw the ‘dragon teeth’ for the first time as the trucks crossed into enemy country. The buildings at Brand were in fine shape and several other Evacuation Hospitals were located there together with the 44th, one being the 102d Evac. Here, medical cases predominated until after 23 February, when the push across the Roer River began. The enormous artillery barrage beginning at 0300 aroused many as it literally shook the buildings of the compound. During this period the Hospital had the distinction of taking casualties from the famous Remagen Bridgehead and heard from the lips of the wounded the story of the crossing. Here admissions totalled 4581 with 1497 operations, a number being one-leg amputations due to the German ‘Schuh mines’. Meanwhile Colonel J. F. Blatt had returned on 22 February and resumed command.

On 14 March orders came to take to the field again. Brand’s comfortable buildings were left behind and the unit followed the First Army’s advance across the Roer to an airstrip close to the village of Dunstekoven, not far from the larger town of Miel, some 10 miles west of Bonn. Here the unit found no difficulty in making the transition to the field after spending over 5 months in buildings, a tribute to the efficiency and stamina of all. The combined functions of an Evacuation Hospital and of an Air Evacuation Holding Unit were carried out with the help of some other medical units. Operations were now run by the 91st Medical Group.

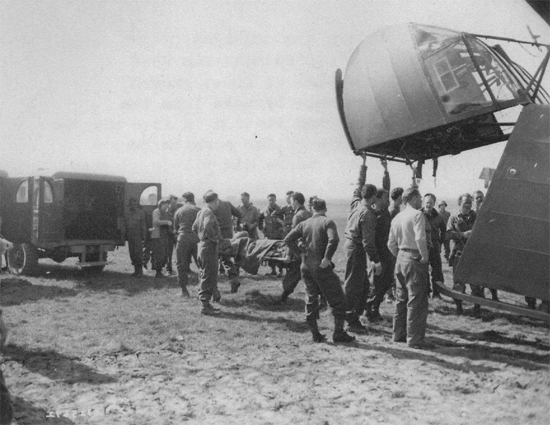

On 24 March 1945, the 44th Evacuation Hospital became the FIRST medical installation to receive gliderborne patients. Two gliders, each carrying 12 casualties, were picked up from a small airstrip across the Rhine and near the 51st Field Hospital and towed safely by a single C-47 plane to the Hospital, and released, patients were all received in good condition. The Hospital closed here the same day with 1030 admissions and only 69 operative cases. The Rhine was now crossed on a ponton bridge near Bonn and the unit set up on a freshly cleared airfield at Eudenbach. These airfields were handling all First United States Army casualties and often C-47s were to be seen taking off with three types of casualties: the light ones to be hospitalized in France – the medium ones going to England – and the long term cases going to Paris for transhipment to the ZI; the Chaplain often advised the latter group to be most thankful! On 27 March, the growth of the bridgehead brought both the 44th Evac and the 45th Evac Hosp across the Rhine to Honnef. During the period large numbers of released PWs, American and British (i.e. RAMPs -ed), came through the Hospital, many with evidence of malnutrition. Rain, mud, and cold were especially bad at this station and plans were made for the forward movement of the Hospital by air, but this was later abandoned. Operations came to a close on 7 April with 1288 admissions and 513 operative cases.

Litter teams pertaining to the 3200th Quartermaster Service Company (24th Quartermaster Battalion), evacuate the remains of victims of the Baugnez shooting (i.e. Malmédy Massacre) to Malmédy for further processing and autopsy.

An all-day trip now took the personnel across central Germany to a bivouac site near Wrexen. Here the unit rested until 15 April when another long forward movement took place. Nordhausen became the scene of the last battle casualties. The final burst into this part of Germany had been a costly one and probably put the greatest strain on the 44th for a brief time that it had endured. On 16 April, the movement to Nordhausen occurred, the bulk of the Hospital arriving at 1100 with 150 patients already there, patients being admitted at 1500 hours even before all tents were up. During the first 56 hours, 1348 casualties were admitted and the Hospital capacity was expanded from 400 to 650 beds. Admissions one day were 523 with 391 evacuations, and on another day they reached 619 with 515 evacuations. Approximately 200 civilians and enemy wounded were bypassed to civilian and other military Hospitals. The majority of the admissions were from the 3d Armored and the 9th Infantry Divisions. In all, while installed on the Nordhausen Airfield, the unit received 2234 admissions and operated on 614. The installation was closed on 4 May leaving a Detachment to care for the non-transportable. After the first terrible rush of Nordhausen was over, many had time to see and visit some of the ‘interesting’ and ‘moving’ sight of the war … there was the enormous Airfield, on which the unit, along with Medical Clearing Companies, was located, Allied bombers had destroyed the gigantic hangars, but what made a man’s blood boil were the sights and stories of the Concentration Camps there. The Advance Detachment had seen one of these, liberated by VII Corps, where the starved and emaciated bodies had literally been stuffed into closets, under steps, or piled like firewood ready for the crematory. The Commanding Officer required the citizens of Nordhausen to give those bodies a decent burial, but what most personnel saw was the gigantic camp erected for the underground V-2 factories (Dora-Nordhausen –ed) where thousands of forced laborers (i.e. mostly political prisoners from occupied countries –ed) had been required to work under extreme conditions.

It was at Nordhausen that the tragic tidings of President F. D. Roosevelt’s death on 12 April reached the unit.

V-E Day … the end:

On 5 may, the Hospital moved southward to the airfield at Gotha where the orders were to prepare for the reception of a large number of ‘RAMPs’ or ‘Recovered Allied Military Personnel’ (mainly American and British liberated PWs -ed). The unit prepared for this assignment but for some reason nothing happened and the Hospital never opened. Three days later, on 8 May 1945 the news came that everyone had anticipated – the unconditional surrender of all German Forces to General D. D. Eisenhower and his staff in the little schoolhouse at Reims, France! Naturally there was much rejoicing and the men flung a big party to celebrate, but to many it was a little anticlimactic as the news had been well-known for several days.

According to available records, the 44th Evacuation Hospital from 19 June 1944 to 12 May 1945 admitted at total number of 22,648 patients and passed 9,363 through surgery. It is interesting to note that there were no Nurses replacements during combat.

Wounded soldiers are being unloaded from a cargo glider at an airstrip (Y-60 Supply & Evacuation, operated by IX Engineer Command) near the 44th Evac Hosp at Dunstekoven, Germany. The glider had a capacity for 12 stretcher cases, accompanied by 1 or 2 Nurses. Picture taken 24 March 1945 in Germany (during Operation “Varsity”).

Immediately following V-E Day the unit moved into the Gotha Aircraft Works buildings and took life easy for a while, swimming, bowling, attending a circus, and making numerous sightseeing trips to places of interest nearby.

On 4 June 1945, orders were received to set up a Medical section of the Hospital (10 Officers & 78 EM) on the race course at Leipzig, some 100 miles to the east. Their duty was to process Russian DPs and transport them to Torgau from where they were to be repatriated to the Soviet Union. A total of 2215 people were funnelled through between 4 – 22 June. The unit then passed under Seventh United States Army control as from 15 June. Due to Government agreements made with the Russians, the Hospital was required to evacuate Gotha and move on 29 June to Landkreis Rotenberg. The Hospital was set up on site as a ‘Rail Evacuation Unit’, opening again as a limited 80-bed unit for patients on 12 July. Until the end of the month a mixed bag of 284 patients were received.

Extensive entertainment, sports, and other recreational programs took place while stationed at Rotenberg. A number of Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men spent a never-to-be-forgotten week in Bavaria and the Austrian Tyrol, taking in Nuremberg, Munich, Oberammergau, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Innsbruck, Brenner Pass, Salzburg and other noted tourist attractions. The 44th however continued to operate actively until replaced by the 24th Evacuation Hospital late August of 1945, and both units lived in Rotenberg for the rest of the Hospital’s stay in occupied Germany.

While at Gotha, ASR scores had been established and 6 of the highest point Enlisted Men had been sent back to the US. On 20 June, the unit was established as a category IV unit, meaning that the low-point men would be transferred to another unit, and the high-point men made into a carrier unit to return to the ZI for inactivation. On 29 June instructions were received to transfer all low-point personnel to the 93d Evacuation Hospital, a category II unit for a quick trip home, to be followed by redeployment to Japan! On 16 July Colonel John F. BLATT assumed command of the 93d Evacuation Hospital, and Lt. Colonel William S. PARKER took over the 44th Evacuation Hospital to bring it home! From this time, there were rapid shifts of personnel – 5 high-point Officers, including Captain Hal E. Houston and Major Julius Sader flew home. Many of the high-point EM were transferred to the 69th Infantry Division and other units for return to the ZI. High-point Officers and Enlisted personnel from the 93d Evac as well as some from the 13th and 63d Field Hospitals came to the 44th Evac. The unit informally ended its existence the week of 8 – 15 July when the big transfer with the 93d took place! In fact the old 44th was gone forever!

The carrier unit which the Hospital had now become, received a considerable number of battle-scarred 5th Armored Division veterans. Rumors about the trip home circulated thick and fast, but it was not until 20 September when what was left of the unit boarded some third class German coaches for a three-day filthy ride to “Camp Philadelphia” near Reims. In that vast camp, morale which had already gotten depressing, hit absolute zero, it was unbelievable that this could be the same Army which had so completely crushed and routed the Nazis, now that its objective had been achieved …

A few all-day trips were made by personnel to the sites of World War I battlefields, some again enjoyed the visits to Paris and wondered at the Reims Cathedral. In the main, the majority hung about camp waiting for travel orders. After several weeks they finally came and the unit left for “Camp Philip Morris” near Le Havre. Again it was ‘hurry-up and wait’, and the men again had to endure another week of watching the bulletin board with sailing dates. Finally the 44th Evacuation Hospital was set to sail on 10 November 1945 from Le Havre, France, on the S/S “Thomas C. Barry”, a converted South American Liner. After a week during which some heavy storms were encountered, she entered Boston Harbor on 20 November, where everyone disembarked and entrained for Cp. Myles Standish. The machinery of deactivation was swift, and the unit saw an end to its World War 2 mission on 21 November 1945.

The original Unit History was gratefully received courtesy of Mike Keane, whose Father, T/Sgt John J. Keane (ASN:12166375) served with the 44th Evacuation Hospital in the European Theater of Operations during 1944-1945. The original story was put together by Chaplain/Captain David B. Walthall, with additional data and illustrations provided by the MRC Staff.