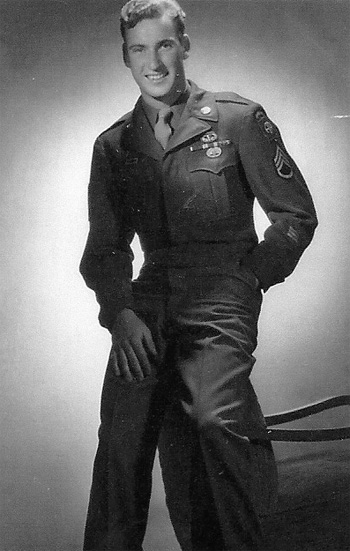

Veteran’s Testimony – Duaine J. Pinkston Medical Detachment, 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82d Airborne Division

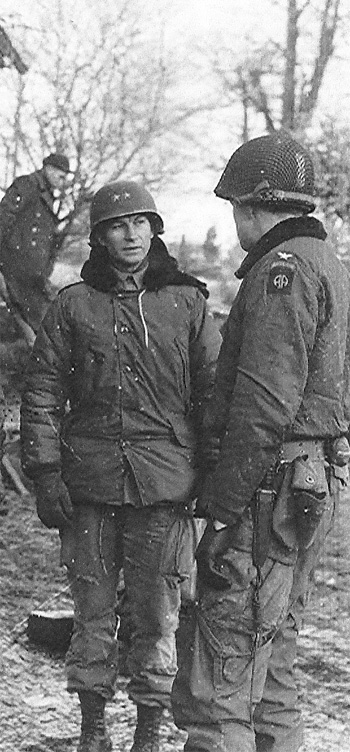

1945 photograph illustrating Staff Sergeant, Duaine J. Pinkston, ASN 36424314, Medical Detachment, 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82d Airborne Division.

Introduction:

My name is Duaine J. Pinkston. I was born 30 May 1924 in Shaftsburg, Shiawassee County, Michigan (not far from Bath, Clinton County). By the time I was about to start school the family had moved to Ionia County on a farm. I hailed from a family of 5 children, and was the only boy (third in order of birth) among 4 sisters; Thelma, Nola, Ruth, and Geneviève.

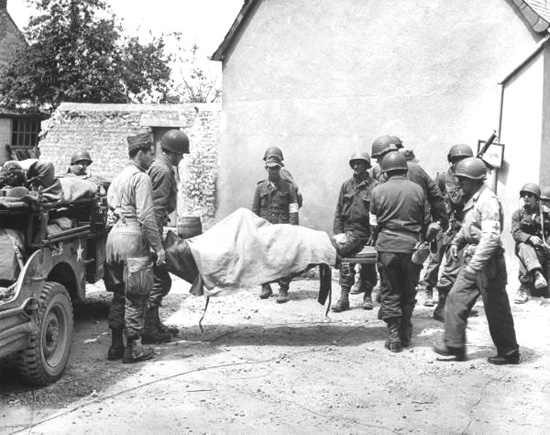

American Medical Officers and German medical personnel getting organized after preliminary negotiations. Picture taken in front of Regimental Aid Station # 2, Hospice, downtown Sainte-Mère-Eglise, Normandy, June 1944.

Enlistment:

After spending eight years in Grammar School, and one year at Ionia High School, graduating in 1942, I got my papers from the Selective Service and took the Army physical. While waiting to be called up for service, I decided to try and wait for enlistment until after the end of the hunting season (as a young man I loved hunting). I was finally called in and inducted on 30 January 1943 at Kalamazoo, Michigan, officially entering active service on 6 February 1943, and sent to Fort Custer, Battle Creek, Michigan (Military Police Replacement Training Center –ed). My Army Serial Number 36424314 indicated that I was a draftee in Sixth Corps area, including the States of Illinois – Michigan – Wisconsin. Fort Leonard Wood, Rolla, Missouri (Engineer Replacement Training Center & Division Camp –ed) was where I was ordered to follow 12 weeks of basic training. Then some of us had a look at the tests required to get into the Air Corps, I wanted to become a fighter pilot. We studied hard for the tests with only 6 of us successfully passing. Then we had to wait for a possible opening.

In the meantime, while waiting for a possible assignment and opportunity I filled in as an Administrative Clerk (MOS 405, Clerk-Typist –ed) and this became my first Army job. During that time I took 17 weeks of advanced medical training, achieving the status of a Medical Private (MOS 409). Although this involved quite a lot of study and practice, I really didn’t mind because as a small kid, I’d always wanted to be a doctor … during this long period of waiting, airborne recruiters visited the different Army Posts and Stations in the Zone of Interior in order to recruit potential paratroops. My Army job became a routine and I figured I had had enough of this, so, after talking to the recruiter, me and some of the boys elected to volunteer for the airborne. After signing the transfer papers, we received orders three days later to report to Fort Benning, Columbus, Georgia (Army Ground Forces Training Center & Infantry School –ed), to attend Jump School. Upon arrival we joined the 542d Parachute Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Colonel William T. Ryder, being assigned to the unit’s Medical Detachment (CO > Major Wolf). I ended up making a total of 21 jumps, both in training and in combat.

Medical Detachment Officers in front of the Regimental Aid Station # 2, Sainte-Mère-Eglise. Left: Captain Alexander P. Suer (Regimental Dentist), right: Major Daniel B. McIlvoy (Regimental Surgeon).

I graduated from The Parachute School and obtained my jump wings 11 September 1943.

542d Parachute Infantry Regiment (Separate) > activated 1 September 1943 at Fort Benning, Georgia, and assigned to the Airborne Command. Joined the Replacement & School Command 29 February 1944, where it was downgraded and re-designated the 542d Parachute Infantry Battalion (utilizing the personnel from the original 3d Battalion –ed) on 17 March 1944. In anticipation of Operation “Neptune” D-Day operations, the organization was to furnish Replacements for service in the E.T.O. The Battalion was relocated to Camp Mackall, Hoffman, North Carolina, and eventually disbanded 1 July 1945 –ed.

During the above period extra training was provided at the Maxton-Laurinburg Army Air Base, North Carolina, where glider orientation and technique were taught. Numerous exercises, including hikes, bivouacs, and field problems took place in the Chattahoochee National Forest and River area, Fannin County, Georgia.

Incoming casualties brought in at Regimental Aid Station # 2, Sainte-Mère-Eglise. American and German medical personnel worked together at the facility, including a number of civilian volunteers.

Sometime during the above period, there was a call for overseas replacements; the Airborne Command immediately needed 26 EM for replacements in the European Theater. Some of us volunteered and were assigned to different Airborne units; 13 men went to the 101st Airborne Division – 12 joined the 82d Airborne Division – 6 (including myself) were assigned to and joined the 505th Parachute Infantry (82d A/B Div). Preparation for Overseas Movement was as an airborne replacement destined for the E.T.O.

As far as I remember, we were briefed and processed, shipping out 23 March of 1944 bound for the United Kingdom as part of a convoy of ships crossing the Atlantic. Our first destination was Belfast, Northern Ireland, where after arrival, this was 3 April 1944, I got assigned to the Medical Detachment, C Company, 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, of the “All American” Division (having moved from Naples, Italy, to the United Kingdom, where it arrived 9 December 1943 –ed). A shortage of adequate training facilities and the lack of infrastructure for airborne maneuvers in the area handicapped the division; this became increasingly important with the attachment of the 2d Airborne Brigade, (activated July 1943 and ordered overseas December 1943 –ed) including Brigade Headquarters & Headquarters Company, and attached reinforcements such as the 507th and 508th Parachute Infantry Regiments. Preparations were therefore made for the “All American” Division to move to the English Midlands. The entire division eventually moved to Leicester, England, 13-14 February 1944, where an intensive program of airborne and other training was begun in view of the forthcoming airborne operations in Europe.

On 22 March 1944, our Regiment received a new CO, Lt. Colonel William E. Ekman, O-21190, MC, relieving Lt. Colonel Herbert F. Batcheller, O-19939, MC, who was sent to command the 1st Battalion of the 508th PIR. The 505th PIR’s strength mainly consisted of 2,095 men, to be carried in 117 aircraft, and to be dropped over Normandy as part of Force “A” (parachute element). Additional personnel would follow, either by glider (Force “B”), or by sea (Force “C”). 1st Battalion would be part of Serial 19, taking off from Spanhoe Airfield (AAF-493), in C-47 aircraft pertaining to IX Troop Carrier Command, 315th Troop Carrier Group, 52d Troop Carrier Wing, planned to jump over DZ “O” (Ste-Mère-Eglise) on 6 June 1944.

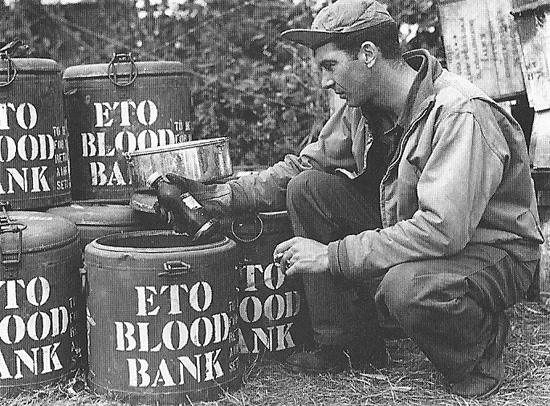

Normandy 1944. Army Air Force personnel checks the contents of an ETO Blood Bank container.

By 26 May 1944 all plans and preparations had been completed for the Division to carry out the mission assigned it by First United States Army. Field and administrative orders had been published and distributed, operation plans had been outlined, and all Regimental and Battalion commanders briefed thoroughly on the prospective Division operations.

France:

“…33 days of action without relief, without replacements; every mission accomplished; no ground gained ever relinquished (Major General Matthew B. Ridgway, Commanding)…”

For training we used so-called sand tables. Air Corps reconnaissance and intelligence specialists carefully reviewed aerial photos and mapped out the target area where we were to jump on D-Day. The DZ was then reconstructed in miniature in a sand table for everyone to study. When we had become familiar with the details we could then become quickly oriented as soon as we had landed, even in darkness. The mock-ups were very detailed, showing streams, railroads, towns, and main highways. We worked on them for an hour and a half every day.

Normandy June-July 1944. ETO Blood Bank supplying blood by truck to the frontlines.

Waiting while being confined to the airfield, we were ready to leave for combat, although we personally didn’t know the objective. I had a buddy in C Company by the name of Pennington (Private Clarence L. Pennington, ASN 34728142 –ed) from Tennessee and this guy could really sharpen knives, so I got him to sharpen my M2 knife. It was kept in a zippered pocket high up the M-1942 coat just in case we had to cut ourselves out of our harness after a jump. We watched a Mickey Rooney movie and then enplaned at about 2245 in the night of 5 June. I recall seeing the white (and black) stripes stick out on the many aircraft fuselages and wings, a special method to help identify Allied aircraft. We got about 20 men to a plane. I normally weighed about 170 lb, but with my equipment I weighed 290. I carried two medical pouches filled with the necessary instruments, bandages, plaster, safety pins, tourniquet, burn injury and eye dressing sets, emergency medical tags, etc. Some men had extra equipment either strapped onto their equipment or leg bags attached. I was lucky, as our plane carried extra cargo bundles with medical supplies that could be released by a toggle switch near the exit door. Of course, I did not carry weapons, but other members of the Regiment did. Some guys hailing from Texas had written home for their own handguns and would carry them into combat. Loving to hunt, I could fire almost anything the others had and had qualified with the M-1 rifle on the range.

My first combat jump took place over Normandy during Operation “Neptune”. My outfit, C Company, left Spanhoe Airfield, England, around 2300 hours, 5 June, and jumped at 0205 hours, on 6 June 1944. I participated in the airborne assault as a member of the Medical Detachment, C Company, 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry, and was no. 2 in my stick (our jumpmaster was S/Sgt Herman R. “Zeke” Zeitner, ASN 39384232). Although our aircraft was hit by 20mm fire just before the “green’ light went on (when our plane was hit, it banked over sharply, then went into a dive before the pilot was able to straighten it, and I almost landed in the cockpit; after I got up, the men pushed me back toward the door as I was number 2 in the stick, we were almost down to treetop level by then but our pilot succeeded in gaining more altitude to allow for a less risky jump) the complete stick dropped on the correct Pathfinder area and joined the assembly point located at a farmhouse near Baudienville, NE of Sainte-Mère-Eglise, Normandy, around 0300 hours. When I landed, nobody was around. It is amazing how you can be spread out from your fellow jumpers. I felt very tired and just lay still for a few seconds before getting out of my chute. I got oriented and crawled over to the edge of a pasture. The moon was out, I distinguished a gate and there sat a machine gun – it was one of ours. Soon I heard somebody coming my way and I said “flash”. A voice said, “Don’t shoot, please don’t shoot! I forgot the damn countersign.” It was Bob Lehman (Robert F. Lehman, Med Det –ed), another member from my stick. We could hear some shooting in the distance but saw nobody around. Once in a while one our planes got hit, knocked out by enemy flak. Some pilots took evasive action trying to avoid the tracers or the searchlights. Suddenly another aircraft came down on fire with a whole string of paratroopers rapidly baling out. I said to Bob, “We’d better take the gun.” We had been toughened by our daily five-mile hikes around Quorndon. Bob picked up the gun along with his load and I got hold of the ammo and we took off. We soon ran into 1st Lieutenant Gerald N. “Johnny” Johnson (CO C Co). He asked us “Do you know where we are?” I replied “Right, where we’re supposed to be. If everything is correct, there should be a Pathfinder post over that hill.” Our Pathfinders preceding us had indeed set up the “Eureka” gear and lights over the hill. We got there, told them we had brought a machine gun and about that time some more stragglers showed up and one of them said, “We can’t locate our machine gun.” We handed over the weapon and the ammo, although it wasn’t the one they were looking for.

Medical Detachment Officers with captured enemy Kettenkrad. From L to R: Captain Byford I. Hall (2d Battalion Asst. Surgeon), Captain Ludwig J. Cibelli (1st Battalion Asst. Surgeon), and Captain Gordon C. Stenhouse (1st Battalion Surgeon).

After setting up a temporary Aid Station at the farm, about 20 jump and combat wounded were brought in for treatment. 1st Lieutenant Stephen Wasecka, O-1295466; 2d Lieutenant Richard H. Brownlee, O-1310566; Private First Class William Galperin, ASN 32080411; and Private Geraldo Colombi, ASN 39127956; C Company Officers and Enlisted Men slightly injured during the jump, joined the group of patients. They were all eventually evacuated to the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion, First Engineer Special Brigade, stationed on Utah Beach.

As daylight came through 1st Battalion left the road to Baudienville, proceeding in the direction of Neuville-au-Plain, moving toward its objective, the bridge over the Merderet River at La Fière, collecting and recovering both personnel and equipment bundles, and by 0830 hours held the eastern end of the bridge against the enemy. Our Regiment would later assist the 507th PIR during its attacks of 8 June 1944.

505th Regimental Aid Stations

Regimental Aid Station # 1 – farmhouse in the field amidst the DZ, midway between town and La Fière bridge, approximately 2 miles away from Ste-Mère-Eglise

Regimental Aid Station # 2 – Hospice building, downtown Ste-Mère-Eglise

While we were on our way to the bridge, I suddenly heard a roar of artillery shells passing overhead that landed in the marshlands behind us. We finally got to the bridge we were supposed to hold and defend, and this we did with heavy loss of life! We managed to hold the enemy back with a single 57mm AT gun, a few .30 caliber light machine guns and some bazookas. One time three of our guys came to me within thirty minutes with their eyes shot out, they had been firing at the enemy over the bank and were hit by rifle or mortar fire. They were not bleeding that much, so I sent them over a little knoll and told them I would be with them as soon as I could. I had other patients of which I had to stop their bleeding if they were going to make it. They sheltered behind the knoll and I heard the explosion of a shell hitting and thought; “Oh, oh my God.” The Germans sent in tanks toward the bridge, but thanks to the heroic efforts of our men, these got knocked out! Our losses were heavy all our Officers had been either killed or wounded. In the meantime we were totally ignorant how things were on the beaches? We were supposed to receive armor support from the 4th Infantry Division, but the tanks never made it that day.

The Regiment lost Major James E. McGinity, O-23257, the first day (6 Jun 44 –ed). Major Frederick C. A. Kellam, O-20376, and Captain Dale A. Roysdon, O-414812 where killed the next day (7 Jun 44 –ed), while Captain Anthony M. Stefanich, O-1287431, was wounded in combat. The third day we were relieved. We had lost 37 men and suffered many wounded.

After 22 days in the field I was hit, receiving some shrapnel in my back from an airburst, my first combat wound (this happened on 28 June 1944 –ed). Those shells would explode 12 or 15 feet above us, making us dig down in a bank. “Zeke” had just had a cup of coffee and I was preparing another cup on the Coleman burner while he dug another hole. I heard the shell coming in and dove for the half-finished foxhole landing right on top of Sergeant Zeitner. Then my face went numb and I told “Zeke” I was hit. He said there was nothing there but dirt and then I felt blood running down my arm. A jeep was called for and I was immediately evacuated to one of the Utah Beach medical installations (most probably the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion –ed) in Lieutenant’s Evans’ FOB jeep. They discovered that I had been wounded in the back, and retrieved a piece of shrapnel under my shoulder blade, not far from my heart. After having been patched up with a drain in my wound, they said to have somebody look at the wound and pull the tube out a ¼ inch every day. One of the medical staff asked if I wanted to be evacuated to England. I told him I’d better return to my outfit, being short of medical personnel, but was talked into staying for a while. A truckload of food arrived at the hospital just as I was ready to leave. Some men loaded the jeep with additional rations including rice, raisins, and milk for our guys. I hurried back to my outfit, and “Zeke” said; “I want to show you something.” The Coleman stove and my canteen cup had been blown to pieces and the coat I had been sitting on had sustained a big hole; there was also a hole in the ground that bottomed beyond my reach! Captain Stenhouse (Gordon C. Stenhouse, O-327543 –ed), called me back to the Aid Station for a few days until my wound was completely healed. This Officer was the 1st Battalion Surgeon, while Staff Sergeant Fred B. Morgan Jr. (Med Det, ASN 11046757 –ed) was in charge of the Battalion’s medical personnel (I was to later get his job). After the drain was removed I re-joined C Company and stayed with them until we were relieved and returned to England.

We took quite some losses during the fighting, often being subjected to heavy enemy artillery fire. While steadily advancing across the Cotentin Peninsula, the fighting got worse, with the enemy putting up a desperate defense. One time I was walking around looking for casualties to evacuate, when I came across a German MG position. I returned to call in some of our rifle men who managed to kill the gunner, and when I later approached the position, I discovered an 18-year scared and wounded enemy soldier. I gave him some water, bandaged him, and when our Platoon Sergeant showed up he questioned the prisoner and offered him a candy bar (the wounded man thought he was going to be shot). After some discussion, the Sergeant and I carried our German patient packsaddle-wise back to the Aid Station.

Medical Officers – 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment

Lieutenant Colonel Wolcott L. Etienne, O-22277, MC (Divisional Surgeon)

Major Daniel B. McIlvoy, O-417858, MC (Regimental Surgeon)

Captain Robert Franco, O-423669, MC (Asst. Regimental Surgeon) WIA 27 June 1944

Captain Alexander P. Suer, O-400651, DC (Regimental Dentist) DOW 1 February 1945

Captain Donat L. Savoie, O-463596, DC (Regimental Dentist)

Chaplains – 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment

Father Matthew J. Connelly, O-442200, ChC (Catholic Chaplain) WIA 7 June 1944

Father George B. Wood, O-471681, ChC (Protestant Chaplain)

Medical Detachment, 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment

Captain Gordon C. Stenhouse, O-327543, MC (Surgeon > 1st Battalion)

Captain Ludwig J. Cibelli, O-1687166, MC (Asst. Surgeon > 1st Battalion)

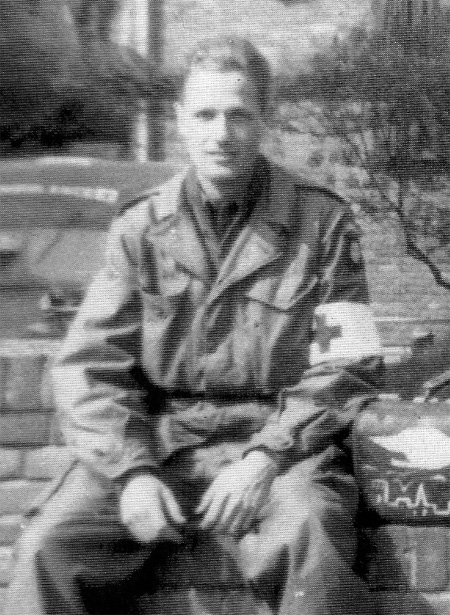

Group of Medical Detachment, 1st Battalion, 505th PIR personnel in Normandy. Back row, from L to R: James R. Rogers, Kelly W. Byars, John W. Clancy, Gordon C. Stenhouse, Ludwig J. Cibelli, and John Valiga, Jr. Front row, from L to R: George M. Patrick, William A. Smith, Fred B. Morgan, Jr., Charles W. DePue, and Guy Campbell.

Between 17 and 20 June 1944, we finally got hold of our barracks bags, which helped us clean up, shave, and changes clothes. A large number of transfers took place, with Officers being shifted from Battalion to Battalion, and some new ones joining from Division. I was written up for a Silver Star for my actions during the Normandy campaign, but refused it (though it would have certainly helped boost my ASR score later). It is important to note that at the time only infantrymen could be awarded the Combat Infantryman’s Badge (CIB), while there existed no such award for medical personnel! Some of the Regimental Commanders submitted requests for the CIB for Medical Detachment personnel (although unofficial, there were some discussions on this ‘touchy’ subject which were published in Yank Weekly –ed); C Company fellow soldiers even volunteered some of their savings to come up with the extra $ 10.00 collected on behalf of the medics (extra combat pay that accompanied the CIB award –ed) which of course we all refused – we just did our job!

After 33 days of combat, the 82d Division was relieved by the 8th Infantry Division and shipped back to England on 13 July 1944. The Regiment lost 186 men in Normandy. C Company members were awarded 25 Purple Hearts and 7 Oak Leaf Clusters. We went in with 176 men and only 36 of us came back. The Medical Detachment received 23 Purple Hearts and 2 OLCs. A short period of rest and relaxation followed with the personnel being granted a number of passes and furloughs to visit England, before re-organization and re-equipment took place, including arrival and assignment of replacements, and more training activities.

Picture illustrating one of the Medical Detachment, 505th PIR’s ambulance vehicles (3/4-ton Dodge Ambulance).

Division was withdrawn moving down to Utah Beach where it waited for the LSTs to bring it back to England. On our way back to the United Kingdom, Fred Morgan and I had managed to secure a Luger pistol (German pistol 08 model 9mm –ed) in the field, and some of the sailors wanted the pistol, so we asked what they had for trade. One guy got hold of a gallon can of pineapple from the galley and we traded. Fred and I emptied the can and drank all the juice and neither of us got sick on our trip. When we returned to Camp Quorn, we went back to our tents. That’s when we really missed the guys we had lived and trained with before; in Normandy we were often strung out so we didn’t know who was missing or not. There were only 2 men in my tent… Next morning we got up rather late, it was 0930. One of the fellows quartered with us had a 10 shilling note, and had said (prior to Normandy); “Hey you guys, listen up, I’m putting this banknote under the wooden floor of this tent. For the guys who come back I’d want to use this money and go downtown and have a drink.” “Zeke” and I were the only two men to come back and went to look for the 10 shillings. The place had been all cleaned up during our absence and the money was gone! We felt miserable, not for the missed drinks, but that the money left by a buddy who got KIA was gone.

Holland:

Upon its return to the United Kingdom 19 July 1944, the Division re-assembled in the Leicester area. Training was again taken up and additional replacements processed. We received a bunch of replacements and it was our job to train them. In the meantime, the newly established First Allied Airborne Task Force was all set for its participation in Operation “Dragoon”, the assault against southern France planned for 15 August 1944 (neither the 82d nor the 101st Airborne Divisions participated in this airborne operation).

A large-scale ground and airborne operation was now in the making for an important Allied thrust to the east, toward Germany. It was in fact a compromise between American and British plans with the aim to pursue German Forces beyond the Seine River, reach out for the port of Antwerp (Belgium), secure a bridge across the Rhine River near Arnhem, Holland, and establish a bridgehead over the Rhine River, north of the Ruhr. The ambitious plan, code-named Operation “Market-Garden”, involved the US 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions, the British 1st Airborne Division, and the Polish Airborne Brigade.

Photo of Captain Robert Franco (Assistant Regimental Surgeon).

1st Battalion would be part of Serial A-9, taking off from Cottesmore Airfield (AAF-489), in C-47 aircraft pertaining to the 316th Troop Carrier Group, 52d Troop Carrier Wing, planned to jump over DZ “N” (Groesbeek) on 17 September 1944.

My second combat jump occurred during Operation “Market”, the airborne assault against Holland. One notable incident took place during the operation; during out flight over Holland S/Sgt “Zeke” Zeitner, jumpmaster, while trying to identify the correct DZ, lost his balance and fell out of the aircraft. He was fortunate to land safely but had to walk nearly 2 miles to rejoin his Platoon. I now became the temporary jumpmaster, and as soon as the ‘green’ light switched on, I had all the stick leave the airplane at once. As for the Normandy jump, we had studied the sand tables closely and the DZ looked familiar to us. The fellow who had prepared the mock-up was from Denmark and had also been in Normandy.

Our Company lost its CO, Captain Anthony M. Stefanich, O-1287431, on 18 September 1944, while clearing one of the LZs for incoming gliders (he had already been slightly wounded in Normandy on 7 June 1944 –ed). One of the regimental tasks was to establish blocking positions south and east of Groesbeek, Holland, and to secure LZ “N” and protect it against any enemy attacks coming from the Reichswald. It all happened when two of our Platoons started moving across a field where the locals were growing turnips and cabbages, and were all strung out in the open without any protection when here came German fighter planes. I was never so scared before, but unfortunately there was nothing we could do, except keep running. Only one of our guys got hit in the arm, and the wound was not too bad. One moment I looked at Sergeant Zeitner, and heard a “zing”, and a shell hit between us. Scattered as we were, we escaped unhurt, and continued our advance to the Reichswald. As we approached the area, the Germans could not train their guns on us, so there we had them, and they had us. After we had taken and secured that extra open ground, one of the gliders (carrying personnel and equipment of the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion –ed) went in right over our heads. One landed just beyond us, near some German positions on the edge of the Reichswald, and Captain Stefanich yelled; “Hey, you guys, com’on, let’s help them.” He jumped up and started running when I saw that German. He was almost a quarter mile away and I saw him pull up and shoot. I told the man next to me that there was a German; he tried to grab his rifle to shoot the enemy but couldn’t, then I saw a paratrooper give chase, stop, and shoot the German. About ten minutes later, Lieutenant Gus Sanders (one of the Platoon leaders –ed) came up and told me Captain A. M. Stefanich had just died and told us what had happened. I said; “Gee! I saw that German shoot.” A buddy of mine, Kenneth H. Lau (C Co –ed) was shot by a sniper and died for I could do nothing for him. We took a lot of casualties in this operation. What made it tough for the medics, was that you had to go out right where a soldier had been hit, bend over to take care of his wounds, and evacuate him to the rear.

Photo of Captain Donat L. Savoie (Dental Officer).

We had a little kid named “Rocky” who had recently joined us. I talked him to try and make him feel at home, he was a member of the gang. We looked down into a depression and saw a German, a tall guy he must have been seven feet. He was a big bruiser; Some of the men took a couple of shots at him but he just turned around and looked at us. We were out near a haystack in front of all the rest of the guys who were waiting along a tree row. Then all of a sudden came the Germans. Some of our guns wouldn’t fire because they were jammed with the sand. 1st Lieutenant Gus Sanders was shooting at them with his .45 pistol. I went back to the other side of the tree row and heard the firing. Pretty quick I crawled out there and saw some of our men lying there. When I reached them, there was our “Rocky”, shot in the back of the head. I could deduct from his tracks that he had turned around and shot the big guy, but when he ran off somebody shot him in the back of the head. I then crawled back to take care of our guys – the ones still living. I was going through the ditch when Lieutenant Johnson came up and said; “Hey Pinky, there’s a German out there and he looks hurt pretty bad. Suppose you have a look?” I thought if I went over there I would get shot at and for a German I hesitated, was this worth the risk? The Lieutenant was a real good egg. He told me that the German was still moaning. He said, “Have you looked at him?”, and my answer was “No.” He continued: “We’ll cover you.” He had a fellow called “Jungle Jim” with a BAR to cover me, just in case. I moved slowly in the direction of the wounded man and there was a German Fallschirmjäger Leutnant. He had been shot right across the stomach without piercing any organs. When he saw me, he just said: “Gut, gut, gut.” I administered a shot of morphine, put sulfa powder on his wound, took some bandage and tape and wrapped that around the wound. I was just about to continue wrapping him up when the shooting erupted. I dove in a shallow ditch and started crawling away. The enemy kept on firing and suddenly they opened up with some 20mm Flak gun over there. It wasn’t hitting me but its bullets exploded against the nearby stone wall with shrapnel flying all over the place. I got my arm knocked from under me and then I felt something wet flowing over my hip. The firing slackened and I was able to run for a bigger hole, though some of me stuck out. After reaching the other side of the wall I found Sergeant Simon H. Hannig (C Co’s First Sergeant –ed) and said: “I’m hit!” He asked me where. I put my hand behind my back and he stood there and just laughed – some bullet had found its way through my canteen. What I had felt proved to be water! Nevertheless I was hit in my arm and the fragment is still there, bothering my elbow from time to time. Al Fowlks, another medic, went out and took over. He was killed that night.

I usually sleep about seven hours, but after being out there and shot at, and with all the strain, with not much food or drink, and enemy tanks running loose all night long, I got back to the Aid Station established in a concrete building to rest. Captain G. C. Stenhouse gave me some blankets and told me to get some sleep. I slept for eighteen hours. When I woke up, Bob Lehman brought me some food. I took one mouthful but couldn’t eat. The Captain said: “He can’t eat that. Fix him some soup.” I went back to bed slept twelve more hours and after that had some soup. I lost 29 pounds in that affray. This happened on 22 September 1944, and was my second combat wound. After treating a wounded Fallschirmjäger Officer, I was shot in the middle of my body, and evacuated to the Regimental Aid Station, where I remained three weeks convalescing. We were sure all glad to be relieved by Third Canadian Corps elements by 12 November 1944.

On 16 November the 505th entrucked for Leopoldsburg, Belgium, where it bivouacked for the night, leaving for Suippes, France, the next day. Lieutenant King Stone, O-1324203, our Graves Registration Officer (who joined the Regiment as a replacement while stationed in England and was assigned to Headquarters & Headquarters Company), secured an abandoned German truck, and kept busy recovering the many 505th PIR casualties, evacuating the dead to the temporary Division Cemetery (opened 20 September 1944 –ed) near Molenhoek, Holland. The 505th lost 140 men in Holland.

Belgium:

“… the battles fought in the “Bulge”, ranking on a par with the brightest victories in the Division’s history, also proved again that plans and matériel are important but the most important and essential of all is a fighting heart and a will to win. To the officers and men of the line goes full credit for the brilliant record they made in the name of the “All American” 82d Airborne Division (Major General James M. Gavin, Commanding)…”

After the failure to break through across the Rhine River, the situation in Holland settled into a defensive stalemate. After over 50 days of combat in Holland, the Division was relieved by the Canadians and the men returned to the Reims area, France.

Photo of Father George B. Wood (Regimental Protestant Chaplain).

General James M. Gavin, acting Commander, XVIII Airborne Corps, was called by his Chief of Staff with the news that he had received a telephone call from SHAEF describing that a critical situation had developed in the eastern frontlines, close to the German border. The place was the Belgian Ardennes, and German Forces had managed to break through Allied lines. After a quick assessment of the military situation, it was decided to issue orders to both the 82d and the 101st Airborne Divisions to prepare for immediate movement.

It should be noted that the personnel and equipment situation of our units was rather critical. Ammunition and field rations had not been fully replenished, many weapons were still in ordnance for repair and maintenance, winter clothing had not been issued, training was not yet completely underway, replacements were still coming in, many casualties were still treated in hospitals in France or England, with only few having been released, and quite a few Officers and Enlisted Men were either absent or away on passes and furloughs. Nevertheless, both units had to go: the 82d was attached to V Corps and was instructed to close in the area near Werbomont; while the 101st Airborne was to be attached to VIII Corps, with orders to assemble in the vicinity of Bastogne, Belgium.

The 505th PIR arrived in Werbomont and about midday of 19 December 1944 was ordered to move east to the village of Basse-Bodeux. What shocked most of our men, was the fact that neither the Officers nor the EM really knew much about what to expect; where were the Germans ? What was the location of enemy and friendly forces ? There was no information and maps were not available … the only method was to send out reconnaissance parties, assess the local situation, deploy and wait for the enemy. Once in contact, orders were to stop him, drive him back, and try and destroy him!

I got wounded for the third time when stationed in the vicinity of Arbrefontaine, Belgium, 3 January 1945. After succeeding in delaying and partially blocking the advancing enemy spearheads, it soon became time to take the initiative. As part of a possible counterstrike, an attack was planned including elements of 4 different units, whereby the 505th would try and capture the high grounds including the villages of Noirefontaine, Reharmont, and Fosse.

Photo of Father Matthew J. Connelly (Regimental Catholic Chaplain).

The attack against Fosse, in the Belgian Ardennes, was particularly bloody. 3 January was a day I will never forget; the Division was to attack and C Company was part of the left flank together with other men pertaining to the 505th PIR, and elements from the 517th PIR and the 551st PIB. Because of the immense cold, sweat froze on the bodies, and as it started to snow it got even colder. The majority of the men were not properly dressed for winter and it was hard to overcome the bitter cold. The Germans were dug in on the slopes, with mortar, artillery, and armor support behind them. While waiting for another company to come up and align with our flank, we were unexpectedly hit by enemy artillery which killed and severely wounded about 45 men in less than a half hour. After subsequently re-organizing, a new attack through the woods took place where we assaulted dug-in MG positions while trying to gradually advance on the slope of the hill leading toward Fosse. We all suffered terribly from the cold as no overcoats, blankets, or food could be brought up, with the re-supply of ammo and water, as well as the evacuation of the wounded receiving overall priority. The extreme weather conditions made soldiers feel miserable, cold, and hungry, and because of the snowfall and negative temperatures, casualties could not always be immediately evacuated or recovered with wounded from both sides dying from exposure. One day, Sgt H. R. Zeitner and I were looking for food and came upon a house. He went to the front with his Tommy gun and I went around the back and waited quite a long time before opening the door. There sat 5 Germans and one of them had a pistol. We found some cheese and a loaf of bread.

Trench foot and frostbite began to take their toll too. I was still wearing leather jump boots, some men had the double-buckle version, but the leather would get wet. That’s when we teamed up taking off boots and socks, wringing out socks and rubbing one another’s feet for 10 minutes to keep from getting trench foot. It was only later that we were able to secure shoepacs which had high leather tops and rubber feet and 2 pair of heavy white wool socks. Some guys were lucky and had overcoats and arctic overshoes.

Photo of Captain Gordon C. Stenhouse (1st Battalion Surgeon), while in Holland, September 1944.

The next action took place near Arbrefontaine. This time, our men got some armored support, a platoon of tanks, and our advance seemed so rapid that we caught an understrength German Infantry Battalion who believed they were safely located in a rear area. Two of the attached TDs caught 2 German panzers refueling and managed to destroy both of them. Around midday a German Officer riding in a captured jeep accidently drove into the 1st Battalion’s OP and was ambushed. A map was found on his body indicating the unit’s move to replace lost personnel. Major Talton W. Long, O-1288410, 1st Battalion CO, quickly rounded up some troops and a Sherman tank moving out to attack the German Battalion. After the Sherman got knocked out, two squads of B and C Company (led by our S/Sgt “Zeke” Zeitner) struck the enemy with the help of 2 tanks (748th Tank Battalion –ed), advancing through a firebreak in the woods. Over the crest the men found themselves in the middle of a German position and continued to fire until some Germans began to leave their foxholes with hands in the air. After the firing died down, a large number of enemy soldiers stood all around us surrendering and “Zeke” (who spoke fluent German) told a German officer to re-group his men in a column including the walking wounded. When news of the attack reached the Battalion, they despatched a truck with a driver to pick up the wounded. After we had rounded up the enemy casualties (miraculously no Americans were killed), I discovered that the young driver was gone! I therefore decided to drive the truck myself, with on board 21 wounded German prisoners, and take them to our Aid Station. I was unarmed (as per the Geneva Convention) but took the risk anyway. I just couldn’t leave the men out there in the open in the freezing cold as they would have stood no chance of survival.

The fighting was so severe that the strength of the Rifle Companies reached a new low, and on 7 January 1945, C Company lost its last Officer, when 1st Lieutenant Richard H. Brownlee, O-1313566, was wounded by an enemy shell. S/Sgt Herman C. Zeitner, being the highest NCO at the time, took over the company until arrival of 1st Lieutenant Dean L. Garber, O-1304059, sent by Regimental Headquarters. Due to the precarious situation of the personnel, I was now in charge of all the medics of C Company. We must have had 39 men in my Platoon, and after that bloody night, there were 19 of us left. At the Regimental Aid Station, Major Daniel B. McIlvoy, Jr. insisted that I get some sleep. Next morning a driver and I took the truck back to the area, some four miles away. We discovered a German under canvas. I thought that if he could make it through the night in the bitter cold, we had better take him back.

Photo of Captain Ludwig J. Cibelli (1st Battalion Asst. Surgeon), also taken in Holland, September 1944.

The Regiment was pulled back from the line and went to Theux, Belgium, for a well-deserved rest from 11 to 25 January 1945. On 23 January I received a field promotion from Private First Class to Technician 5th Grade. The Division then moved to XVIII Airborne Corps reserve. We departed Theux at night entrucking for Born, and later regrouped for the next operation in the assembly area of Meyerode, before participating in the attack against Losheimergraben, the Siegfried Line, and the German border, to be launched on 28 January … after successfully pushing forward, the 505th was finally relieved by the 508th Parachute Infantry on 3 February. Trucks were waiting for us at Losheimergraben and carried us to Salmchâteau, near the Salm River, where the men were able to take hot showers for the first time since leaving France and received new clothes. After this period of R & R, the first replacements started coming in, including survivors of the 509th and 551st Parachute Infantry Battalions being transferred to the “All American” Division (despite the flow of replacements and the return of troopers from hospital, the Division remained understrength –ed).

It was always heartbreaking to see all those young dead American soldiers. As medics, we did what we could to save as many lives as possible, always caring for the wounded, and trying to recover the dead whenever possible, sometimes with support of Quartermaster Corps Graves Registration personnel.

Germany:

By early February 1945 Division was about to enter the Hürtgen Forest, a place where many American units had been literally chewed up before. The place looked horrible, totally devastated, with debris, abandoned vehicles, decaying bodies, hardware and ordnance scattered everywhere. I can tell you that what we witnessed in the Hürtgen Forest left a lasting impression. Moreover the place was a sea of mud. While over there, I recall a young machine gunner replacement going berserk. When he discovered the two dead replacements he had arrived with the day before, he went running and bawling into the forest. There were still mines and booby traps everywhere so I ran after him, caught up with him, tackled him, and kept him on the ground for a while. After talking some sense into the poor fellow, I finally got him walking again in the right direction, back to our lines. The young soldier was sent to the rear suffering from ‘combat fatigue’; imagine, the guy had just arrived…

On 18 February 1945, the “All American” was relieved by the 9th Infantry Division. Finally by 20 February, the 505th was withdrawn after re-assembly at Aix-la-Chapelle, returning to Suippes, France in the now familiar “40 & 8” boxcars. Suippes was reached on 22 February 1945 with the personnel now being housed in tents and badly in need of rest, equipment, and replacements. With the arrival of additional personnel, there was a re-organization followed by numerous promotions and changes in command. Major James T. Maness, O-342184, recently promoted, took over command of 1st Battalion. Parades and reviews were held, decorations and ribbons awarded, and more training took place, including practice jumps, in order to rebuild units decimated in the earlier fighting. Wild rumors circulated that we were to jump across the Rhine River in order to open a way into the “Fatherland”, followed by another one, stating that the 82d would jump on Berlin … all rumors were soon dispelled when we heard that First Army had seized a bridge over the Rhine, the place was called Remagen!

Group of 505th PIR Staff Officers at Suippes, France, before the Bulge campaign. From L to R: Major James T. Maness, Lt. Colonel James E. Kaiser, Colonel William E. Ekman, Lt. Colonel Edward C. Krause, and Major William R. Carpenter.

I was wounded once more while in Germany on 12 March 1945. Luckily the wounds I sustained were of a minor nature and did not require hospitalization.

By late March 1945, the 82d Airborne was engaged in training activities at its bases in Sissonne, Suippes, and Laon, France. Early April 1945, Division was ordered to relieve the 86th Infantry Division and occupy a line extending north and south of Cologne. The orders for the Regiment were to control the Rhine River south of Cologne and north of Bonn and conduct aggressive patrolling.

Movement by rail and motor convoy began early on 2 April and upon arrival Division Headquarters was set up at Weiden, Germany. Active patrolling and improvement of the defensive sector constituted the unit’s major activities, gradually being expanded to sending out small parties across the river to reconnoiter potential areas for occupational duties and conduct searches for enemy soldiers and caches of arms and ammunition. Casualties were frequent, mainly caused by uncharted enemy minefields and random artillery and mortar fire. Positions fronting the Rhine River were set up with several listening posts along the river manned at night. Any movement though, when observed by the enemy, was risky and immediately brought artillery or mortar fire from across the Rhine. While in the sector, the Battalions were ordered to send patrols across to look for information and bring back prisoners for interrogation.

The sudden death of President F.D. Roosevelt (12 April 1945) caught everyone by surprise and made us feel very sad. Hitler thought it would change the way the war was going, but it didn’t.

The “All American” Division carried on Military Government (occupation) duties in the Cologne area, Germany. Guards, administrative personnel, medical teams, security details, and intelligence groups were provided for any recovered RAMPs, and DPs, while bridges, ammo dumps, minefields, and PW enclosures, were located and marked for further action. At the end of the month, troops probed enemy defenses east of the Elbe River and on 30 April the 505th successfully forced a crossing with snow and rain keeping the enemy ground troops in their shelters, except for some artillery fire. Initial crossings were made by the 1st (A & C Companies –ed) and 2d Battalions (D & E Companies –ed), supported by B Company, 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion and by nightfall a small bridgehead had been established east of the Elbe River, in the vicinity of Bleckede, Germany. Unfortunately the planned artillery barrage stopped before the assault boats arrived. When it started raining, it snowed later during night, waiting for the boats and not knowing how the enemy would react, was utterly nerve wracking. We all made it safely across, and what was really surprising was the total lack of enemy resistance. Some of our troops even captured a few Germans apparently sleeping in their positions. Elements pertaining to C Company, found a number of enemy soldiers in a barn nearby a farmhouse; they were Hamburg policemen, recently conscripted into military service and offered no resistance.

After bringing in additional support, a general plan of attack was laid down with all airborne units moving ahead aggressively. By noon of 2 May 1945, our troops were in Ludwigslust. Meanwhile many units of the German 21st Army were being cut off and surrounded, and consequently started surrendering en masse. At 2130 hours, 2 May 1945, the CG, 82d Airborne Division, accepted the unconditional surrender of the German 21st Army (approximately 144,000 men –ed).

Photo illustrating Maj. General James M. Gavin (CG 82d Airborne Division) talking to one of his Regimental Commanders. Period: Battle of the Bulge, winter 1944-45.

First contact with our Soviet Allies took place during 3 May, after which the main activity consisted in directing the PWs and any liberated Displaced Persons to the rear and to set up camps to receive them, and process the large numbers of recovered Allied PWs. We discovered their presence by hearing some voices on our radio network speaking a language we didn’t know. We found one of our men who knew Russian and he said they must be Soviet troops! The Russians and us stopped with only 8 miles between us. Colonel W. E. Ekman met them that same night.

One of the activities that the troopers used to pass the time was to organize horse races. Many of the animals had been confiscated (probably from an Hungarian cavalry troop, captured by G Company –ed) during the German surrender and for about a period of two to three weeks the Regiment set up a proper racetrack, designated “Sour Kraut Downs”, where betting was widely tolerated. Some of the men familiar with horses, or ex-farmhands, even performed as real jockeys during the races. They unfortunately didn’t last long, as Division had to move on.

On 5 May, Division elements discovered a concentration camp north of Ludwigslust (Wöbbelin), where they were confronted with a repulsive and horrible sight of emaciated survivors barely living amidst large numbers of dead and dying inmates dressed in wretched and striped uniforms. The citizens of Ludwigslust including some of the leading German civilian and military authorities had to dig graves for 200 inmates (a symbolic number) and attend the special funeral on 7 May 1945, as ordered by General Gavin. As a medic I had seen many men die in combat, but this was simply revolting and horrifying and the sight of the survivors staring at us, uncertain about what was going to happen to them, with fear in their eyes, was something I had never before witnessed in my life. We treated and handled the minor injuries, but mostly took any wounded back to the 307th Airborne Medical Company toward Ludwigslust.

SHAEF Headquarters then issued the news that the Germans had just signed the documents of unconditional surrender of all German Forces to the Allies, at Reims, France. The war in Europe was over – it was V-E Day!

Division was alerted late in May 1945 for movement back to France. Advance parties were sent out, with the main body starting its journey by rail and truck on 1 June. Meanwhile control of the area was relinquished to the British who took over as occupation forces 11 June 1945.

Between 12 and 15 June, Division moved to Epinal, France, and a few weeks later we received the news that the 82d Airborne had been selected to occupy the American sector in Berlin, the former German capital city. They would be known as “America’s Guard of Honor”. The different echelons started moving around the end of July 1945, entraining on the familiar “40 & 8s” for a 5-day journey to Berlin, well inside the Soviet Occupation Zone, arriving between 1 and 8 August. Being short of the necessary points, I accompanied Division to its new duties in Berlin, Germany, from August to October 1945.

End of a Military Career:

During our stay in Berlin, Germany, I managed to secure a number of furloughs for the 1st Battalion medics. We had two fellows who had gotten married in England and I knew they’d want to go back. We had some choice and could visit a number of places and countries. I got the furlough that was left and spent some beautiful days at the French Riviera (US Army Riviera Recreational Area –ed). The weather was beautiful in September, and I enjoyed some food like back home. It only cost me $ 7.00 for the eight-day stay in Nice, southern France (city reserved for Enlisted personnel –ed). One day after a swim I was sitting there chatting with a buddy and then heard a familiar voice. The man was all excited, he was the one who had made the sand mock-ups for Normandy, and he told me that he was starting back on a visit to Denmark. He was happy to see that I had made it through the war. I told him that when I jumped, the DZ was just like if I had been there before and thanked him for he had done a really good job building the sand tables.

With the war being over in Europe, everyone was ready and anxious to return home and get discharged! The new Redeployment & Readjustment program (RR-1) and the individual Adjusted Service Rating scores (ASR) were important factors to determine the future status of a unit and its personnel. What we were looking for was whether we would be able to accumulate the necessary number of “points” (two groups of men – high pointers – had already returned to the ZI –ed). I was finally able to reach the required 85 points to become eligible for Discharge (as my ASR score on 2 September 1945 was only 84 points, I had to decide to extend my stay with the 505th and serve longer). The Regiments were now actively processing lists of the respective high-point personnel to be discharged

Having been promoted to Staff Sergeant after the Bulge, I was now in charge of the 1st Battalion’s medical personnel (Medical NCO, MOS 673). In October of 1945, the Detachment held a big party for the men leaving the European Theater for the Zone of Interior. Being now part of the group with a sufficiently high ASR score, I started my trip on 20 October 1945, eventually leaving the ETO via Le Havre, France, sailing for Newport News, Virginia, and the United States. We arrived at Camp Patrick Henry, Oriana, Virginia (Staging Area for Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation –ed) on 13 November 1945, where we stayed for approximately 1½ day for processing. While being there, we were treated like kings, being stuffed with all the good food we had missed for so long. We couldn’t have enough of it, and even bought some extras at the Post PX as well!

Ambulance Jeep (of an unknown unit) in the Belgian Ardennes, during winter.

On 16 November 1945 I was transferred to Camp Atterbury, Columbus, Indiana, where I received my Separation Papers, and was Honorably Discharged from my duties to Uncle Sam on 18 November 1945!

After the war I took advantage of the G.I. Bill and went back to school. After some time I got a job with General Motors where I was able to negotiate and obtain some extra possibilities from the GM Institute to continue my uncompleted education. In the meantime I married June Johnson on 19 January 1947 in Ionia, Michigan, and continued working for GM, bought a farm, and quit for an early retirement at the age of 52 … We have 3 children Craig – Karen – Brian, and have been married 65 years.

Campaign Awards

Normandy

Rhineland

Ardennes-Alsace

Central Europe

Personal Awards

Purple Heart (GO # 10, 1944, 505th PIR, dated 5 Aug 44)

Purple Heart OLC (GO # 11, 1945, 505th PIR, dated 12 Mar 45 + GO # 43, 1945, 505th PIR, dated 12 Jul 45)

Medical Badge (GO # 29, 1945, 505th PIR, dated 8 June 45)

Wounds sustained in Combat

France – 28 Jun 44

Holland – 22 Sep 44

Belgium – 3 Jan 45

Germany – 12 Mar 45

Special thanks are due to S/Sgt Duaine J. Pinkston (ASN:36424314), who served with the Medical Detachment, C Company, 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in the European Theater, participating in 4 different campaigns, including 2 airborne assaults (Normandy + Holland), during which he was wounded four times. The MRC Staff wish to express their gratitude to the Veteran and his Family for kindly sharing documents and personal reminiscences used in this Testimony. Further thanks should go to Airborne Author and Historian, Michel De Trez, for having allowed us to borrow quite a few illustrations from his book “Doc McIlvoy and his Parachuting Medics” (No. 3 WWII Paratroopers Portrait Series).