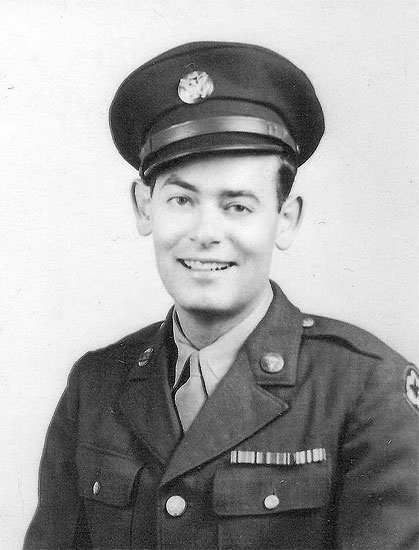

Veteran’s Testimony – Martin Lipschultz 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company - USAHS "Acadia"

Private Martin Lipschultz, ASN 32696728, 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company.

Introduction:

My name is Private Martin Lipschultz, ASN 32606728. I was born on 24 May 1921 in Essex County, New Jersey and spent 4 years in College graduating as a Pharmacist (Rutgers College of Pharmacy, Newark, New Jersey). My nickname during my service years was “Lippy”. I became a Pharmacist (MOS 149) with the U.S. Army Medical Department, on board the USAHS “Acadia” and served on the ship during WW2.

I joined the Army on 12 January 1943 with hopes of serving FDR’s newly established Pharmacy Corps, developed to improve medical care for servicemen and their families. Had I known that my Pharmacy would be afloat, I might have joined the US Navy instead (as did my brother). I was to spend my entire Army life aboard a Hospital Ship, not one day free from seasickness. My official date of entry into active service was 19 January 1943, my first Station being Ft. Dix, Wrightstown, New Jersey (Training & Pre-Staging Center, with an acreage of 28,344, and a troop capacity of 1,825 Officers and 51,598 EM).

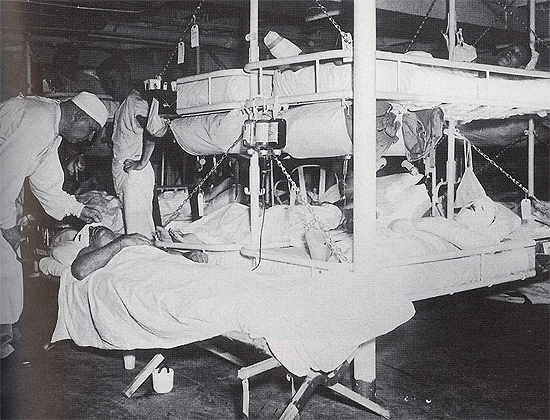

Hospital ship, typical layout of a ward.

Following Basic training in Charleston, South Carolina, I was assigned to the 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company. My main interests then were baseball, basketball, and boxing. Before the war I fought Reddy Russo in the ‘Lightweight – Golden Gloves Championship’ (132 lbs) in New Jersey. I was to meet another boxer, a real Flyweight (112 lbs) champ, better than I was, Jimmy Connelly from New York City. Always looking for a little diversion, Jimmy and I had fun organizing boxing exhibitions aboard our ship. Unfortunately, the war would interfere with most of my activities.

During World War 2, the means of transporting sick and wounded personnel from Evacuation Hospitals in the combat zone to a Hospital in the Communications Zone (ComZ) consisted of Hospital Trains – Hospital Ships – and occasionally, Motor Convoys and Airplane Ambulances. Improvisations also took place. One of the methods used was transportation of patients to General Hospitals in the Communications Zone by means of Hospital Trains. However, the evacuation of severe cases for further treatment in the United Kingdom or in the Zone of Interior (continental United States) took place by Air and Sea. And that’s why there was a need for Hospital Ships. Although the US Army had no Hospital Ships in the early stages of the war, a Table of Organization for a Medical Hospital Ship Company (this would become T/O 8-537) was drafted by the Surgeon General’s Office early in 1942. Army Hospital Ships were to be manned and operated by ‘civilians’ (Merchant Marine) and by ‘military’ (Army Medical Department personnel to care for patients).

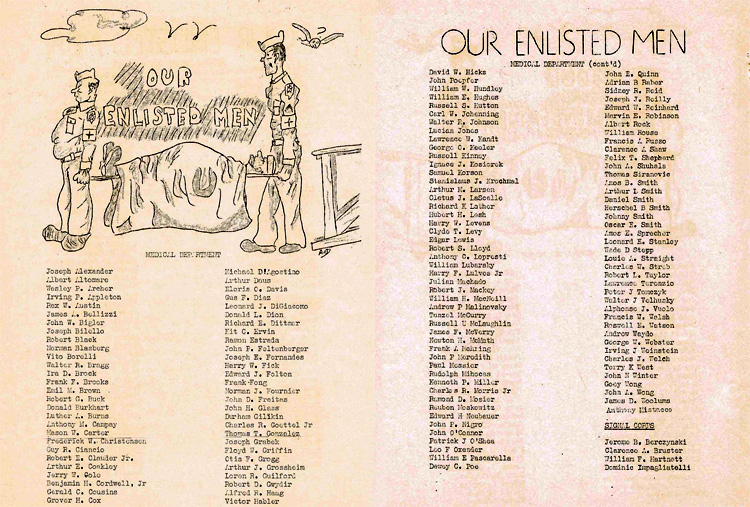

The draft (April 42) of the Table of Organization for a Hospital provided for a Company with unit strength of:

14 Officers

1 Warrant Officer

35 Nurses

99 Enlisted Men

Above was amended in the definitive T/O 8-537, dated 1 April 1942, to read – 12 Officers, 1 Warrant Officer, 35 Nurses, and 99 EM, to basically care for 500 patients, commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel. Supplementary units could be called upon if necessary. They consisted of 2 Officers, 4 Nurses, and 11 Enlisted Men for each additional group of 100 patients.

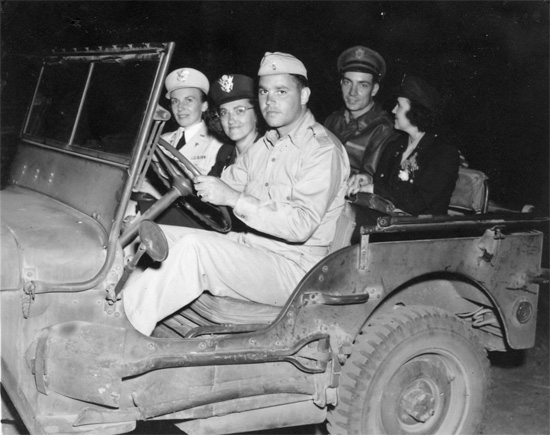

Group of USAHS “Acadia” personnel enjoying drinks during a party held while on leave ‘somewhere’ in North Africa … the person looking over her shoulder (bottom right) is 1st Lieutenant Eleanor H. Winter, ANC. Courtesy Carlie McMahan..

In May of 1942, the WD approved conversion of the ship USAT “Acadia” into, what was called at the time, an “Ambulance Transport”. ETO authorities requested 3 Hospital Ships, and after approval of the necessary T/O, 4 Hospital Ship Companies got activated in October/November 1942. The first complement being reserved for the “Acadia” in December 1942. It was based on experience gained during operations aboard the Acadia, that necessary adjustments and requirements later took place.

Overseas Movement – North Africa:

The “Acadia” was the first combined troop-transport-hospital ship to sail from the United States in WW2 with a full hospital complement aboard. The 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company consisted of 18 Officers, 37 Nurses, and 94 Enlisted Men (it was activated April 1943). At the time of its first trip the German U-Boat menace was far from gone, and the “Acadia” with her precious cargo of troops, would have been a fine target for any enemy torpedo. Seagoing soldiers and nurses discovered the meaning of “to secure” when the ship tossed and rolled, and many a meal was lost when seasickness began to take its toll. It was the 204th’s introduction to “sea” duty.

The first voyage ended at Casablanca, French Morocco, and personnel got their first glimpse of a war-torn country. The ship was to carry the unit many times again to North Africa and its blazing sun, queer foul smells, and strangely dressed natives.

For the next 4 months the “Acadia” would be crossing between North Africa and New York, carrying troops on the outbound trip and wounded patients on the return voyage. Then followed a short break with layover in New York harbor, while the ship exchanged her gray war paint coat for a white and green one. The antiaircraft and other guns, the Navy crew, and the troopship bunks all went off, and after being duly registered under the Treaties of The Hague Convention, the new United States Army Hospital Ship “Acadia” was ready to sail once more.

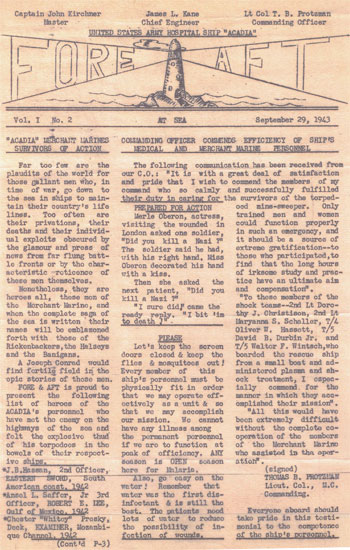

Copy of a news bulletin “Fore and Aft” published and distributed on board the USAHS Acadia while at sea (Sep 1943).

Provision of Hospital Ships could not wait, the North African Theater (NATOUSA) requested 2 Hospital Ships, and the General Staff, after consulting with the other branches concerned, authorized further conversion of the “Acadia” into a Hospital Ship (a second ship was to follow, i.e. the “Seminole”). Both ships were to be stripped of all armament, their hulls were to be painted white, with a horizontal green band on each side, and Geneva Red Crosses on their sides, decks, and funnels, another important feature was that the ship should be illuminated at night, to display her ‘neutral’ status (non-belligerent vessel). Structural modifications delayed the departure of the “Seminole” (until Sep 43), but since the “Acadia” had already been fitted as an Ambulance Transport, it was able to sail out of New York to North Africa on her maiden trip as a “US Army Hospital Ship”, the date was 5 June 1943, and I was on board! As a matter of fact, I was called up for transfer overseas on 3 June 1943.

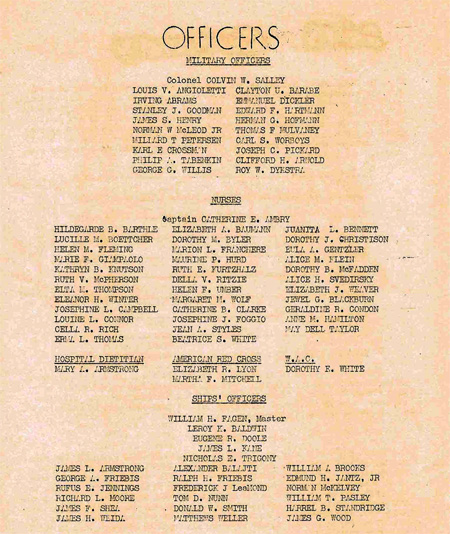

The USAHS “Acadia” was run by Captain John W. Kirchner (Ship’s Master) and James L. Kane (Ship’s Chief Engineer). Lt. Colonel Thomas B. Protzman, MC (204th Med Hosp Ship Co C.O.), Major William V. Barney, ChC (Chaplain), Major William G. Ford, MC (Chief Medical Staff), Captain Louis V. Angioletti, MC (Chief Surgical Staff), Captain Alexander S. Forster, DC (Chief Dental Staff), and 1st Lieutenant Muriel M. Westover, ANC (Chief Nurse) were some of the Officers in charge. The ship was run by the Merchant Marine, but operated by the United States Army (Lt. Colonel T. B. Protzman was later replaced by Colonel Colvin W. Salley, CO of USAHS “Seminole” in 1943, who was to serve on board the “Acadia” until February 1946. The new Chaplains were Captain Thomas F. Mulvaney (Catholic faith) and Captain James S. Henry (Protestant faith); the Chief Nurse was Captain Catherine E. Ambry. The Ship’s Master was Captain William H. Fagen –ed).

Ambulances prepare to unload wounded troops from the USAHS “Acadia”. Courtesy Willis Frick.

At the beginning, British Hospital Ships and Carriers evacuated most of the US Army patients to the United Kingdom (191 in Jan 43 – 111 in Feb 43 – 179 in Mar 43). After having initially used unescorted US Troop Transports to evacuate certain classes of patients to the United States, evacuation was reorganized allowing all classes of patients to be shipped by Transports out of Casablanca (French Morocco) and also later by convoyed Troopships out of Oran (Algeria). Between Jan 43 and Dec 43, they managed to evacuate a total of 16,284 patients. From June onwards, the two Hospitals ships in the area, the “Acadia” with a capacity of 806 patients and the “Seminole” with a capacity of 468, became available for evacuation from other ports in the Mediterranean thus adding extra capacity. The “Acadia” was however too large to dock at Bizerte (Tunisia). Both vessels transported a number of patients back to the ZI (729 in Jun 43 – 467 in Aug 43 – 779 in Oct 43 – 450 in Nov 43 – 1,168 in Dec 43). An average Atlantic crossing took around twelve to fifteen days, and 500 or more patients could be transported on each trip.

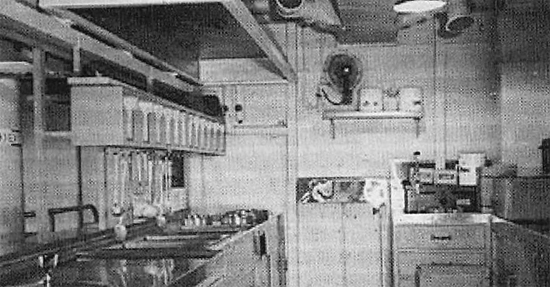

General specifications for Hospital Ships provided for surgical rooms, pharmacy and laboratory facilities, adequate toilets, isolation wards, X-Ray unit, berths of maximum two tiers, and the necessary beds, with as ideal hospital location, slightly aft of midship, and not more than one deck below the weather deck, and relatively close to lifeboats for possible emergency evacuation. Lighting, ventilation, and wide passageways for litter carry were also required. The Acadia had only one small OR, but it did have three other rooms that could be pressed into service in case of emergencies. The available wards were fitted with beds arranged double-decker style. Apart from the std. medical specialties, 1 Dietitian and 2 Physical Therapists were assigned to our ship on her maiden voyage. It later appeared that because of certain limitations and the acute shortage of PTs, their services would no longer be utilized. Nurses’ quarters on board were 4 to a room. If not on duty, Nurses had a midnight curfew, whether at sea or in port. They worked a 12-hour shift at night and a 9-hour shift during day, depending on the type of patients to be treated. To make working easier, Nurses were issued brown-and-white seersucker slacks in lieu of dresses. Of all the original Nurses assigned to our ship, 29 would still be on board at the completion of the ship’s 12th Atlantic crossing.

Due to the limited amount of space available for dining facilities, it was impossible to use the mess halls at the same time. Because of this, different schedules were to be observed.

Officers’ Mess

Breakfast (0815-0845) Lunch (1215-1245) Dinner (1715-1745)

Enlisted Patients’ Mess

Breakfast (0730-0945) Lunch (1100-1345) Dinner (1600-1845)

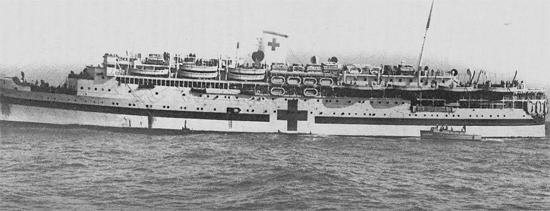

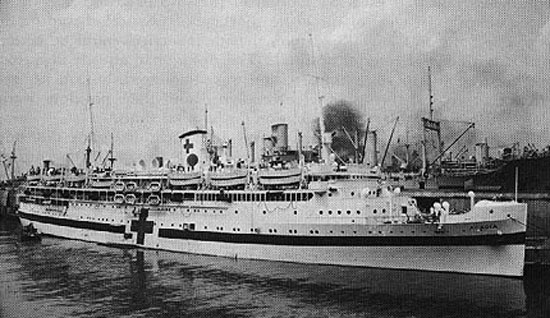

View of the Acadia during one of its World War 2 trips to North Africa.

On 5 June 1943, our ship, gleaming in her brand new white and green coat of paint, and large red crosses, stood out to sea for the first time under a new status – touching at Gibraltar (The Rock) and Mers-el-Kebir (Algeria), she eventually arrived at Oran (Algeria), where she embarked patients for the United States.

Our ship returned from Oran, Algeria, with 749 patients on board, and sailed for Charleston, South Carolina, where it arrived on 25 June 1943. Charleston became some sort of a main station to me, when in the States. The “Acadia” often went out on a mission overseas, to return stateside with a number of casualties, the pattern would have been something like (as far as I remember) a number of months traveling (approximately 4/5 months), and a kind of R & R period in Charleston (some 10 days), and then back out again.Charleston, in South Carolina, eventually became the Port of Debarkation for all Hospital Ships, and the voyage from Europe across the Atlantic usually took approximately 12 to 13 days. Although not the largest port in the Zone of Interior, it ranked as the third busiest port in the country. Charleston was selected as the home port to receive patients for many reasons. Main reasons for this choice were the favorable climatic conditions in the region, its proximity to an Army Air Base as well as available train transportation, and its nearness to a Navy yard should repairs be necessary. Colonel Bertelloni, Superintendent Water Division, Port of Charleston, was head of the reception committee that boarded every incoming ship, and Brigadier General James T. Duke, Commander, Charleston Port of Embarkation was responsible for the welfare of all patients traveling on hospital ships. The debarkation program was generally conducted as follows: soon after docking, the first people to leave the ship were the ambulatory patients, then followed the litter patients. Upon leaving the port gates, members of the Red Cross distributed coffee, donuts, milk, ice cream, and cigarettes. The ride to Stark General Hospital was about 8 miles and following arrival and registration, the patients were assigned to a ward for a short time as it was the desire of the War Department and the Government to place the individual patients in a General Hospital near home, except those who required special care who were subsequently sent to specialized hospitals. The means of evacuation were either by hospital train or by air.

USAHS “Acadia” 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company personnel with Free French Navy personnel.

Picture taken while on leave in Oran, Algeria. Courtesy Joe Cristini.

August 1943 found our ship at Oran, Algeria, where it suffered some damage to one of its propellers after striking some submerged object in the harbor. After a thorough check and some minor repairs, the “Acadia” returned to New York on 25 September 1943 with a complement of American wounded.

The United States Army Hospital Ship “Acadia” was converted from the USAT “Acadia”(USAT-526) transport ship. She was designed by Theodore Ferris and contracted for by the Eastern Steamship Lines (Boston, Massachusetts). Laid down as a 7-deck vessel with 2 masts and 1 stack in March 1931, the S/S Acadia was built by the Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock Company in Virginia and launched 13 February 1932. The ship served as a passenger vessel and primarily ran the New York-Boston-Nova Scotia route from June 1932 to 1938. In 1938 the “Acadia” was commissioned a cruise ship for running between New York, Bermuda, Cuba, and the Bahamas, and became very popular with the thousands of tourists. The same year she attracted national attention by ramming and sinking the famous excursion steamer “Mandalay” in New York harbor. Her efforts contributed to successfully saving the Mandalay’s 40 passengers and crew. In 1939, shortly after Britain declared war, the S/S “Acadia” was chartered to evacuate stranded Americans out of Europe, with which she was occupied for the next 3 years. During one of her return trips Neptune and the elements conspired to test the Acadia’s seaworthiness. Skirting the Azores, merely 3 days out of Ireland, the “Acadia” ran flush into a raging hurricane, knocking the bridge off center, smashing exits on C deck, and flooding decks and compartments beneath the engine room to a depth of nine inches. The gale, abetted by high seas, bore down upon her like a demon. Fighting for her life and badly crippled, she however managed to break through and limp into New York harbor four days late. The “Acadia” also engaged in the transportation and distribution of defense workers and aviation technicians throughout the newly acquired island bases in the Pacific. Three weeks after Pearl Harbor, the “Acadia” was enroute to Panama to evacuate Army wives and children. She remained 3 months in the Caribbean serving first as a transport and evacuation ship, eventually engaging in transporting Axis agents and diplomats out of South America. The ship’s transport duties came to an end when, on 29 May 1942, the Transportation Corps decided to convert her into a Hospital transport vessel. Place of conversion was Boston P/E. After conversion by the Bethlehem Steel Company, which lasted from June to October 1942, the ship emerged as an Ambulance Transport with a capacity of 1,100 troops outbound and 530 patients inbound. She sailed from December 1942 onward in this capacity, until placed under the protection of the “Hague Convention” as a Hospital Ship. After another conversion (by the Bethlehem Steel Company) and additional modifications in New York, She was re-designated US Army Hospital Ship “Acadia” on 3 May 1943, as announced by War Department General Order No. 27, dated 3 June 1943. The ship had a maximum speed of 18 knots. After replacement of the standard bunks by hospital bunks, the maximum patient capacity was reduced to 787. The basic medical staff consisted of 9 Medical Officers (including the CO), 2 Dental Officers, 2 Chaplains, 3 Medical Administrative Officers, 1 Warrant Officer, 37 Nurses, 1 Hospital Dietitian, 1 American Red Cross worker, 1 Women’s Army Corps Officer, and 147 Enlisted Men. After its commissioning as a full-fledged US Army Hospital Ship (the very first Hospital Ship to be commissioned by the United States Army –ed), the “Acadia” sailed for Charleston, South Carolina. The ship’s first voyage took place on 5 June 1943, sailing from New York for North Africa. The USAHS ”Acadia” was finally decommissioned on 11 February 1946, by War Department General Order No. 17.

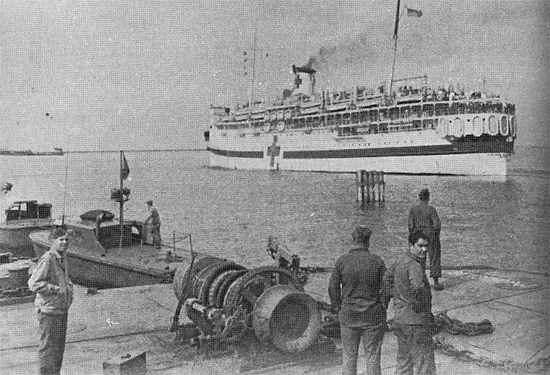

View of the USAHS “Acadia” at the Charleston Port of Embarkation, South Carolina. Courtesy Willis Frick.

First Operations – Sicily:

Our next operation took us to Sicily, after the landing (10 July 1943, “Operation Husky), where we operated together with the USAHS “Seminole” on behalf of the Island Base Section (IBS) and Seventh US Army. Our task consisted in evacuating patients. As large ships, we operated out of Palermo although the docks did not allow direct loading/unloading, so litter cases had to be winched aboard from smaller craft. American patients were routed to Bizerte (Tunisia) and Oran (Algeria). Patients were loaded aboard by means of a block and tackle, and during the battle for Palermo, patients were brought to our ship by LCI barges. Surging seawaters often made loading difficult and litters had to be lifted in rhythm with the waves. Once on board, patients were immediately operated, and then transported to Hospitals in North Africa.

While off the coast in Sicily and on call for the invasion forces, we helped treat casualties from the USS Barnett (APA-5). This particular troopship, part of the amphibious force supporting the landing, was hit by a near miss during a German bombing attack. On 11 July 1943, a bomb burst aboard the USS Barnett’s port bow putting a hole in the hull and causing subsequent flooding. The ship was made to list to starboard and was able to steam away under her own power to the port of Algiers for repairs, where she docked on 15 July. 7 men got killed and 35 wounded, with the latter being taken on board the USAHS Acadia for treatment, before being evacuated to shore.

As a Pharmacy Graduate I was responsible for administrative matters and pharmaceuticals, but very shortly I was to find out this was not the case. Pharmacists on board Hospital Ships were to be flexible, serving where and when needed! Some people called us “medics”.

To keep busy on long and slow days, the crew gave each other bad haircuts and contributed to the ship’s newspaper, “Fore and Aft”. On other days, we restocked the Pharmacy, cleaned the counters, the floors, and gave ordinary injections. When the Nurses or Doctors looked for ‘extra’ hands, we marched to their orders – especially the pretty Nurses.

Some patients just called us “Doc”. During World War 2, we were what would today be considered the “go-to-guys” – we did what was ordered to control the patient’s never-ending pain. The injured who knew they would never make it home, made jokes with us, even calling us “Mom” because Mom always made them feel better – her home remedies were always the best!

Photograph illustrating USAHS Acadia as she appeared during WW2.

Further Operations – Italy:

Being aid men during the Salerno Landings (9 September 1943, Italy, “Operation Avalanche”) we often served as Litter Bearers evacuating patients off the beach while under fire from enemy big guns… During this operation, HMHS “Newfoundland” (Royal Navy), carrying 103 American Nurses on board (the ANC complement of the 95th Evacuation Hospital) took a direct hit from a German bomb on 13 September. The ship caught fire and despite every possible effort had to be abandoned. She was subsequently scuttled and sunk by the USS Plunkett. All the Nurses made it safely to shore and later returned via Bizerte to Mateur (Tunisia) where they were treated at the 74th Station Hospital.

During the early phases of the operation, 2 British Hospital Ships were to handle evacuation from the US beaches at dawn on D+3, while a third ship was to follow on D+4. Casualties were to go to Bizerte (Tunisia). It was only later that US Hospital Ships were requested to help. After D+5, the ships were sent to Italy on request of Fifth United States Army, and then routed back to North African ports as designated by Allied Force Headquarters.

Without a doubt, one particular incident will haunt me forever. I will never forget the morning of September 24, 1943, during an action in the Mediterranean. We were standing apart from the convoy, when my ship received an all out distress call. One of our minesweepers, located about five miles from our ship, had been torpedoed leaving many wounded adrift. Our CO > Lt. Colonel Thomas B. Protzman, MC, directed our ship toward the convoy to render assistance. He sent a small launch with 2 merchant seamen and some volunteer medical staff into the midst of the action. I had no concept at all of what I was about to experience, when I volunteered. The sight and heat of smoke and flames, cries from the wounded, seemed like coming from another world. Up to this moment, many of us were still ‘boys’, and had neither witnessed nor experienced such serious blast and burn injuries. The shelling and bombing forced us to concentrate using hand signals since the noise was so loud it was almost impossible to communicate.

Two Nurses of the 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company are being picked up by their local ‘escorts’ in a ¼-ton truck while on leave in the Mediterranean Theater. Courtesy Carlie McMahan.

Some of the “shock team” who boarded the crippled minesweeper included; 2d Lt. Dorothy J. Christison, 2d Lt. Maryanna S. Schaller, Tec 4 Oliver W. Hassett, Tec 5 David B. Durbin Jr., and Tec 5 Walter F. Wintsch. 33 of the survivors, all suffering from extensive burns, were rushed to the ship for treatment. Half of the Hospital Ship’s supply of blood plasma was used up that same day, saving 31 of the 33 casualties.

The long hours of study, training, practice and teamwork paid off. Our shock treatment teams and plasma administered from a small rescue boat made the difference between life and death. We continued to pull survivors, bodies and mangled parts from the water until ordered back to the Acadia. There, we gave support to the medical teams trying to save these brave men. It was a horrible nightmare, visions I have never been able to erase from my mind! Patients always got absolute priority! A number of instructions and subsequent actions were discussed and implemented. Screen doors were kept closed to keep flies and mosquitoes out (don’t forget malaria was a constant threat). Everyone was instructed to go easy on the water, it was indeed the first disinfectant, and patients required a lot to reduce the possibility of wound infection. Everyone was constantly reminded not to slam doors and avoid excessive noise, especially around the surgical wards on decks “B” and “C”.

Typical view of a ward kitchen.

A few days after the battle, we received a “Commendation for Meritorious Service” from General Dwight D. Eisenhower, praising our Commanding Officer and the members of our unit for their outstanding accomplishments in the care and evacuation of sick and wounded casualties in the North African Theater, and for the action taken on 24 September 1943, saving many lives and giving further evidence of a high degree of efficient training and devotion to duty.

During the invasion of Sicily and Salerno, our ship shuttled between Palermo, Algiers, Bizerte, Ferryville, the Salerno Beachhead, Oran and Mers-el-Kebir. The shuttle operation terminated on 25 October when the “Acadia” set sail for Charleston, SC, its newly founded terminus for debarking patients.

When returning from its 12th crossing to Charleston 9 January 1944, the “Acadia” had its ‘big’ day. The ship was returning to its main port bringing home 776 patients and stories of her arrival had been printed in all major newspapers around the country. For the first time in World War 2, reporters and newspaper men were allowed to attend the arrival of a Hospital Ship.

Charleston, in South Carolina, became the “Acadia’s” official Port of Debarkation. In fact it became the major home port of all Hospital Ships. Charleston had been selected as the hub to receive hospital patients for many reasons, namely because of climatic conditions, its proximity to an Air Base as well as the available rail transportation and its nearness to a Navy Yard when ships needed immediate repairs. Approaching the harbor, patients and crew could view one of the oldest summer resorts in the country, the Isle of Palms, and in the distance, distinguish Fort Sumter, famous during the Civil War. A Reception committee always boarded the Hospital Ship after which it proceeded up Cooper River, about one hour’s sail to the Port of Charleston proper. Following the initial welcome and final docking, debarkation followed along a certain sequence. First, all ambulatory patients would leave the ship, followed by the litter cases. Members of the American Red Cross would then meet everyone with free coffee, donuts, milk, ice cream, and cigarettes. The ride to Stark General Hospital was about 8 miles but was made very quickly under escort of the Military Police. Upon arrival at Stark, every patient was assigned to a ward, while cases that required special care were sent to specialized Hospitals and Hospital Centers. Transportation took place either by Hospital Train or by Air Evacuation.

While serving on the Acadia, I also did participate in the Anzio Landing (22 January 1944, Italy, “Operation Shingle”). The big guns shelled for a few days and bombs dropped by Allied planes on enemy troops fell everywhere. Needless to say our hearing was impaired with each major invasion. The only ear protection we had was toilet paper that we stuffed in our ears! When supply boats appeared, toilet paper was high on our want list. Medicine such as quinine for Malaria was also at the top. Most of us could not avoid bites of hungry mosquitoes. For over 50 years recurring bouts of malaria continue to remind me of the war. The assault received the necessary medical support, with hospitals and medical units trying to move inland as quickly as possible. Hospital ships remained available off the beaches until D-Day + 3, after which they remained on call until requested by the situation on the beachhead.

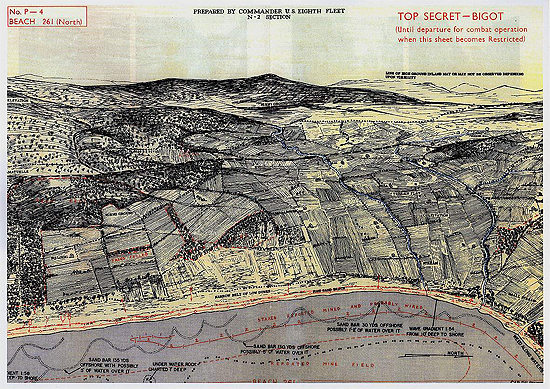

Partial map illustrating some of the landing beaches, prepared by the United States Eighth Fleet, for “Operation Dragoon”, 15 August 1944.

For a duration of 17 weeks Anzio Beachhead was to remain a “flat and barren little strip of Hell”, where Hospitals were only six miles behind the fighting lines and with their backs to the sea! During the early days of the assault, casualties were kept at Battalion Aid Stations or evacuated directly by small landing craft to medical-equipped LSTs. The only medical installation on shore at the time of the landing was the Second Platoon, 33d Field Hospital, which started treating its first patients around 1800 hours. Additional Hospitals were landed on D+1, but were only operational some days later. German air raids on the harbor area, against offshore ships, and enemy long-range shelling made the Hospital sites and evacuation operations almost untenable! Three British Hospital ships were in the area as well to provide additional treatment and hospitalization, but we were all afraid of the frequent air raids and intermittent shelling with apparently had little concern or respect for Geneva Convention symbols. As a matter of fact, a British Hospital Ship, the St. Andrew, was attacked and sunk by German bombs on 24 January.

Pharmacists bounced from job to job. The injured yelled out for a “Girl Friday”, meaning they needed help to write home. After all, we had College degrees, so the general consensus was, we could write. Patients were scared, as we were, and needed someone to talk to. During these moments our job was to listen due to the fact that Chaplains were not always available. In civilian life they might have been considered patients and ourselves healthcare providers – ask any WW Vet, during the war, you are just shipmates too, a very unique situation…

Trypical view of Nurses’ living quarters on board.

After the landing and subsequent inland battles, the Acadia returned stateside carrying a number of casualties from the Anzio Beach assault and the battles that raged around Monte Cassino.

On base we could play baseball, basketball, and football. At sea, since I didn’t particularly enjoy cards, ping pong was my game. I defeated ‘Roby’ Jarvis of the Merchant Marine to win Acadia’s Second Ping Pong Tournament. I was so damn excited over winning a box of candy (as the new Ping Pong champ) that I dropped a bottle of formaldehyde (colorless pungent irritating gas, used chiefly as a disinfectant and preservative) on the Pharmacy floor in the morning. I spent two hours wearing a gas mask while trying to clean it up. Everyone found it amusing; since along with the candy, I had been given the morning off for winning the tournament!

More Operations – Southern France:

The landing in Southern France (15 August 1944, “Operation Dragoon”) was another of my WW2 campaigns. During the initial days of the invasion, casualties were evacuated from the Beach Clearing Stations by small landing craft to the transports, and further carried by LST to Ajaccio, Corsica, for treatment by the 40th Station Hospital. Three Hospital Ships arrived off the landing area on D+1, and more were to arrive later (a total of 12 were to be made available, operating out of Corsica).

Hospital Ships involved in “Operation Dragoon” – 15 August 1944

USAHS Acadia

USAHS Algonquin

USAHS Château Thierry

USAHS Emily H. M. Weder

USAHS Ernest Hinds

USAHS John E. Clem

USAHS John J. Meany

USAHS Marigold

USAHS Seminole

USAHS Shamrock

USAHS St. Mihiel

USAHS Thistle

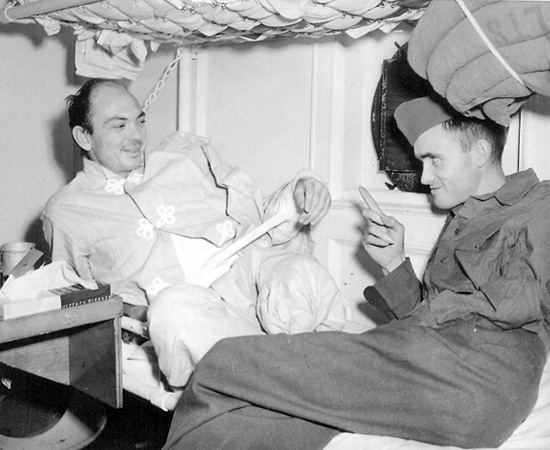

Two wounded soldiers chat in a ward of the US Army Hospital Ship “Acadia”. Left is Sgt. Harvey Fitzgerald and Pfc. Raymond D. Horton is sitting on the right.

We had sufficient capacity to accommodate 788 patients and carried 3 Surgical Teams on board. After D+6, Hospital ships were sent into the area on a one-day-basis until 28 August, and thereafter only at the request of the Seventh United States Army Surgeon. When at first, the Hospital ships called at all three landing beaches, all evacuees were later transported by ambulances to the Clearing Station of the 58th Medical Battalion at Ste. Maxime, where the ships were loaded. Through 21 August 1944 the Hospital ships discharged at Naples, Italy. Between 22 and 29 August vessels loaded to 60% or more with French casualties or enemy PWs were sent to Oran, Algeria.

After the fall of Marseille and Toulon, enough hospital beds became available, and at the end of the month no more Hospital ships were requested by Seventh Army.

Between 18 August and 3 November 1944, a total of 6,277 patients were evacuated by Hospital ships.

On 26 June 1945, the ship arrived in the Zone of Interior carrying 778 wounded soldiers on board all having been evacuated from the European Theater. The human cargo included 420 litter cases, 311 ambulatory patients, and 47 mental cases, all brought in from Cherbourg, France.

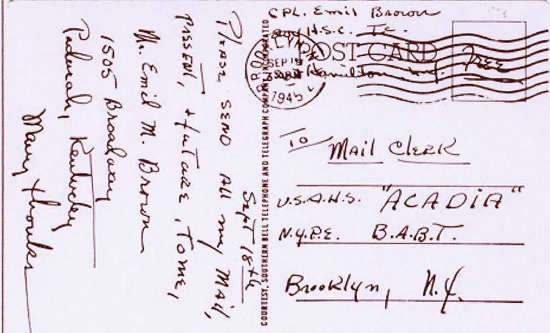

Illustration of a post card dated 18 Sep 45, addressed to Cpl Emil M. Brown (204th Med Hosp Ship Co) c/o the Mail Clerk aboard the USAHS Acadia (private collection).

The USAHS Acadia for the past 2 years (1943-1945) followed close behind the fighting in the MTO and the ETO. While the battle for North Africa was going on in Tunisia, she evacuated casualties from North African ports. She took on board the first wounded from the invasion of Sicily, receiving them from the troop transports which had just returned from the beachhead. A few days after the fall of Palermo, the Acadia was there receiving casualties from the battle raging around Messina. As the Allies threw back the Germans from the hills surrounding Salerno, the hospital ship steamed into the Gulf of Salerno to carry off the wounded. She stood by in a British port while the greatest invasion of all times, the Normandy beachhead was being secured. The invasion of Southern France found her moving on D+1 off shore to embark casualties while the guns thundered nearby. The USAHS Acadia returned to Charleston, 13 times in a period of 2 years (not including her 32 trans-Mediterranean crossings performed while providing “shuttle” service). The USAHS Acadia was considered to be the ‘flagship’ of the Army Hospital Ship Fleet. She had not only participated in almost every Invasion in the European Theater of Operations, but was present in North Africa as a troopship at Italy-Normandy-Sicily-Southern France as a hospital ship, carrying more patients across the Atlantic than any other Army Hospital Ship!

Of the original 204th Med Hosp Ship Co, only 7 Officers, 10 Nurses, and 21 EM remained of the ‘first trippers’, and of the Merchant Marine crew, the only person still on board was Chief Engineer James L. Kane…

The small American Red Cross contingent traveling on the “Acadia” always endeavored to make the trip home as pleasant as possible. The many recreational facilities on board and the tentative entertainment program planned were specially made for the patients, but its success depended largely on the latter’s assistance and participation. While all instruments for a good jam session were available (piano, trumpet, saxophone, guitar, drums, banjo), the men to swing it were necessary, and that’s were the patients (at times supplemented by volunteer merchant and medical crew) came in. At the end of a trip, a variety show was put on with patient talent. Movies were shown frequently too. Arts and crafts were encouraged and work such as block printing, wood and metal work, belt making, basket weaving, plastic work, wood carving, and leather decoration were practised. The ship’s newspaper “Fore and Aft” was published during the different trips with contributions from staff and patients. A library containing about 500 books was available to all, and magazines were distributed as well. Even servicemen who had not been paid were not forgotten. While they could not take loans from the ARC staff on board, they could receive any comfort articles needed, by addressing the ARC worker in their wards and those things were purchased for them. During the voyages, the Special Service Officer and the American Red Cross greatly appreciated the assistance of the ambulatory patients who helped with the distribution of supplies, with the library, and with the daily programs. The many activities included community singing, quiz programs, bingo, ping pong tournaments, horse racing games, musical programs, variety shows, and radio programs and movies.

Photo of S/Sgt Joseph Cristini, member of the 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company, on board USAHS “Acadia”, while visiting Oran, Algeria. Courtesy Joe Cristini.

Water supply was essential and to assure clean linen at all times, a laundry functioned while at sea. Water was often rationed as only some wards had residual salt water taps plus fresh water taps. The majority of the wards had only cold salt water showers, as the fresh water capacity was always limited and was reserved for the treatment of patients.

The food served on board the “Acadia” was the best to offer. The Stewards’ Department and the Hospital Dietitian did all they could to serve an above average diet including such delicacies as fresh milk, chocolate toddy, ice cream, fresh fruits and vegetables, and an assortment of meats far better than what could be secured at home under the current rationing and shortage.

Religious services for Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish Faith were offered on many occasions. Such services included Holy Mass, Novena, Benediction, and Confessions for Roman Catholics on Sundays and week days; Worship services and Devotional sessions for Protestants on Sundays and week days; and Worship services for Jews on Fridays.

A Sales Store (under control of the Sales Commissary) was located in the “D” deck lobby and had available quite a variety of goods including candy, cigarettes, cigars, cookies, and toilet articles such as shaving equipment, tooth paste, and tooth brushes. A rationing system was in effect on board, applying to all personnel, merchant crew, medical hospital staff, and patients. This system allowed to each person 10 packets of cigarettes per week and 5 cigars per day. Chilled coca cola was also made available on alternate afternoons.

All patients and staff who wished to deposit their money and other valuables for safekeeping while aboard ship could do this. Receipts were therefore made available by the respective ward personnel. Anything so deposited could at any time be withdrawn by applying to the Office of the Custodian on “B” deck at 1300 hours each day. Non-ambulatory patients could request assistance from the charge Nurse of their ward. At completion of the trip, all deposits could be either withdrawn or left in which case they were forwarded to Stark General Hospital, or to the medical facility to which the patient was directed, and withdrawn there.

The USAHS Acadia leaves Cherbourg, France, with a number of casualties bound for the Zone of Interior. On 26 June 1945, the Acadia brought back 420 litter cases, 311 ambulatory patients, and 47 mental cases, all casualties of the European Theater.

By May of 1945 the Acadia had made a total of 13 Atlantic crossings and brought home 9,919 patients!

In summer of 1945, it was decided to send the Acadia to the Pacific Theater. After having been fitted with ventilation systems and some tropical modifications, she sailed out of Los Angeles, California, with destination Manila in the Philippines, returning to Los Angeles on 20 December 1945. In January 1946, the USAHS “Acadia” was on her second trip to the Pacific, when at sea, news was received that the ship was ordered decommissioned as a Hospital Ship! After arrival in the Philippines, all Geneva Convention identification was painted out, and after receiving a new coat of gray, she began carrying troops once more, and continued servicing the Armed Forces stations in the Pacific.

Definition: An “Acadian” (personnel serving on old “Cady”) was a guy that worked hard, did every imaginable job at every imaginable time, never got to see much land, seldom cared where he was going, and last but not least he was really quite a fellow (by Tec 5 John A. Wong).

Mixed group of USAHS “Acadia” medical staff. Some of the 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company personnel are wearing the Transportation Corps SSI, while others are not. Photo dated 5 February 1945, location unknown. Courtesy Joe Cristini.

Some of the personnel who made the first voyage overseas of the USAT “Acadia” on 12 December 1942, were still serving on board by end June 1945. They included:

Captain Irving Abrams

Captain Walter Casale

Captain Emmanuel Dickler

Captain Stanley J. Goodman

First Lieutenant Joseph C. Pickard

First Lieutenant Dorothy M. Byler

First Lieutenant Dorothy J. Christison

First Lieutenant Maurine P. Hurd

First Lieutenant Kathryn B. Knutson

Left: Photograph of 2d Lieutenant Catherine B. Clarke, taken while taking courses and working at Bellevue Hospital, New York, at the time, Mrs. Blanche E. Edwards was Director of Bellevue Schools of Nursing and Nursing Services of Bellevue Hospital. Period 1942. Courtesy Kay Richardson.

Right: Photograph of 1st Lieutenant Catherine B. Clarke, while serving in the Mediterranean Theater, most probably taken in Southern France. Period August 1944. Courtesy Kay Richardson.

First Lieutenant Ruth E. Kurtzhalz

First Lieutenant Dorothy B. McFadden

First Lieutenant Elta M. Thompson

First Lieutenant Eleanor H. Winter

Technical Sergeant Clarence A. Bruster

Technical Sergeant Leo F. Oxender

Technician 3d Grade Robert S. Lloyd

Technician 3d Grade Herschel B. Smith

Technician 4th Grade Walter R. Bragg

Technician 4th Grade Raymond D. Mosier

Technician 5th Grade Emil M. Brown

Technician 5th Grade Otis F. Grogg

Technician 5th Grade George W. Webster

Technician 5th Grade Terry K. West

Courtesy of Willis Frick.

Other men and women still serving on 25 June 1945, were on board for the maiden trip of the “Acadia” as a Hospital Ship, which took place 5 June 1943. They were:

Major Louis V. Angioletti

First Lieutenant Helen M. Fleming

First Lieutenant Marion L. Franchere

First lieutenant Alice M. Klein

First Lieutenant Della V. Ritzie

First Lieutenant Beatrice S. White

Technician 4th Grade Dominic R. Impagliatelli

Technician 5th Grade John W. Rigler

Technician 5th Grade William E. Pascarella

Private First Class Eloris O. Davis

Private First Class Richard E. Dittmer

Private First Class Kenneth P. Miller

Private First Class Edward W. Reinhard

The Medical Hospital Ship Platoon justified its existence, and as the number of Hospital Ships increased, 176 Platoons were being used by V-E Day in the ETO, with another 116 serving in the Pacific…

Courtesy of Willis Frick.

Above Testimony and pictures were kindly provided to us by Mrs. Harriet Lennard, daughter of Pharmacist Martin Lipschultz, (ASN: 32606728), who served aboard the USAHS “Acadia” as a member of the 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company in WW2. The MRC staff would also like to thank Carlie McMahan, stepdaughter of 1st Lieutenant Eleanor H. Winter, ANC, and Joe Cristini son of Staff Sergeant Joseph Cristini also members of the 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company, and further Willis Frick, for kindly supplying them with numerous pictures and copies of vintage documents illustrating the Hospital Ship, her medical complement and crew. More vintage photographs were generously shared by Kay Richardson, daughter of 1st Lieutenant Catherine B. Clarke, who also served aboard USAHS “Acadia. Thank you all.