Veteran’s Testimony – Nathan L. Shipkowitz 164th General Hospital

Close up photograph of Tec 5 Nathan L. Shipkowitz (ASN: 36679423). Taken from the Graduation Class photograph at Walter Reed General Hospital.

Induction:

My name is Nathan L. Shipkowitz, I was born on 29 March 1925. I had a High School degree and 2 years of Community College, basic studies. I entered active service at Chicago, Illinois, and received Army Serial Number 36679423. The first number, “3”, means I was drafted into the Army. If you enlisted, the first number was “1” (Regular Army) or “20” (National Guard). The second number, “6” means I was in the 6th Service Command, under Second United States Army jurisdiction. The 6th Service Command included the States of Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, with Headquarters in Chicago, Illinois. The remaining digits 679423 are sequential numbers.

Identification Tags belonging to Nathan Shipkowitz. Notice he has attached a P-38 Can Opener to the beaded necklace.

We were given 2 identification tags to always wear around our neck with a chain. If a soldier was killed, one tag remained with the body and the second tag was nailed to the temporary wooden grave marker. The “Dog Tag” included surname, first name, second initial, ASN, tetanus immunization (with year), tetanus toxoid (with year), blood type, and religion. Religion was indicated by P = Protestant; C = Catholic; H = Hebrew.

In case the soldier had no specific religious preference, no religion was indicated. Jewish soldiers could elect to drop “H” in the E.T.O. and leave a vacant space or replace same with either “P” or “C”, if preferred. The Germans, if they captured an American soldier, were obligated by the Geneva Convention to notify the Army of name, rank, and serial number. But some American captives were Jewish and the Germans singled them out for harsh treatment and possibly worked them to death (fortunately, very few cases were observed).

I was drafted into the Army at the age of 18 years and 3 months. The date was 5 August 1943.

You might be interested to know I graduated from Bowen High School in Chicago when I was not yet 16 years old. I and a girl (Grace DeFelipo) were the class babies. We had our pictures taken for the Year Book. Since I did not have a job and the Army was still two years away I entered Wilson Junior College in Chicago. When I filled out my Army questionnaire I indicated education – 2 years of College. At the Reception Center in Chicago a Navy Chief Petty Officer came over to verify if I indeed had two years of college. I said yes. He said I should join the Navy – more opportunity for advancement since I already had two years of college. I told him I couldn’t swim so I had better stay out of the Navy. He said – “Son, don’t worry – the Navy will teach you to swim”. I was very much interested in medicine and therefore decided to join the Medical Department.

Training:

Photograph taken at Camp Grant in October 1943. Names are as follows:

1. Fidusia; 2. Dariff; 3. Molonini; 4. Reibstein; 5. Lt. Shoeler; 6. Bayt; 7. McDermith; 8. Johnson; 9. Jones; 10. Kessler; 11. McCanna; 12, Morano; 13. Furlong; 15. Feing; 16 Hirch; 17. Shipkowitz; 18. Alexander.

I was transported to Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois (Medical Replacement Training Center -ed) for basic training. Basic was an 8-week course – afterwards you were shipped to a combat unit or sent on for further training. Camp Grant became the first MRTC west of the Alleghanies when the Selective Service System came into effect. President F. D. Roosevelt signed the “Selective Training and Service Act of 1940”on 16 September 1940. The Act provided that no more than 900,000 men were to be in Training at any one time, and limited service time to 12 months (later extended to 18 months). It required any men between the ages of 21 and 36 currently living in the country to register in order to be inducted.

Basic Training at Camp Grant was pretty easy. Reveille was at 0630 because cannon was fired at exactly 0630 each morning, and the “Old Glory” was raised at the headquarters building. The entire camp stopped for this daily ceremony – and everyone faced the flag. Drivers in military vehicles stood at attention next to their vehicle when the cannon were heard. This ceremony was repeated at 1700 when the flag was brought down for Retreat.

Photograph taken in March 1944 of Minna Berry, a student Nurse at the Gallinger Municipal Hospital.

Every day about six soldiers were assigned to KP (Kitchen Police -ed). I had never cooked so I knew nothing about a kitchen, let alone cooking. One soldier got the garbage detail. After every meal the garbage can was weighed. This was to find out if any food was being wasted. The garbage cans were then scrubbed out with soap and hot water, and turned over to dry for the next meal. I was lucky and got assigned to make soup. The cook showed me how to fill the cauldron with water – about 25 gallons. Then I added a brick of fat. Next the cook handed me a small knife. He then obtained a sack of potatoes, a sack of onions, and a sack of carrots. He said, “Peel all these vegetables and start cooking the soup. Be sure to stir the broth”. He gave me a utensil that almost looked like a canoe paddle. Always stir every ten minutes. It took me all day to peel the 3 sacks of vegetables.

When in basic training in preparation for being assigned to a combat unit, one of the exercises was to crawl under barbed wire enclosures to reach our objectives (obstacle course). They fired a .30 caliber machine gun over our heads to be sure we learned to crawl close to the ground. When we reached our objective the machine gun stopped firing and a siren sounded. This was an indication all was clear. Physical conditioning was important and one of the Training Center’s tasks was to teach green recruits to withstand the rigors of combat. Such hardening was accomplished by drill, road marches, calisthenics, and an organized athletic program.

Photograph showing “A” Company Barracks at the Army Medical Center, Washington D.C.

Another time we saw a demonstration of a flamethrower. There were two men in this assignment, both very tall, strong-looking soldiers. The main soldier carried the weapon, which consisted of a flame gun, a pressure tank, and a gasoline tank, on his back. It looked like some large fire extinguisher. The hand-held flame gun was ignited by an electronic system. The second soldier had a rifle and his task was to assist and protect the operator. The flame nozzle was ignited and a terrific stream of fire went out the front of the pipe. You could feel the heat when standing 15 to 20 feet from this action. These flamethrowers were used in securing some of the enemy pillboxes in Normandy. The Germans had built concrete bunkers to protect their cannon, but these flamethrowers could burn them out if they could get 50 to 100 yards from the bunkers.

After finishing 8 weeks of basic training at Camp Grant I was sent to Walter Reed General Hospital (designated US Army General Hospital by WDGO # 83, dated 2 May 1906, multi-story permanent brick building, operational May 1909, with an authorized bed capacity of 3,000, specialized in general medicine – thoracic surgery – amputations – deep x-ray therapy – radium therapy – and psychiatry -ed) in Washington, D.C., for advanced medical training. The living quarters were in Chevy Chase, Maryland, about 5 blocks from the White House. I would often walk past the fence and see the lights burning in the driveway. I often thought, behind those windows is where President Franklin D. Roosevelt was looking over our country’s war strategy.

The training in medical techniques was intensive. We were supposed to be able to diagnose and treat injuries and illness if a medical doctor was not available. I thus became a Surgical Technician (MOS 861) and finished the war with the rank of Technician 5th Grade (Corporal). Little did I realize that the reason for this training had another purpose. When the course was nearly over, an Officer with the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) told us we were trained to accompany small groups of soldiers into occupied France. We would be parachuted at night and met by members of the French Resistance. We would go to Parachute School at Fort Benning, Columbus, Georgia. I think the head of this operation was General William J. Donovan. This was a volunteer operation and anyone could opt out. The clandestine nature of this assignment did not appeal to me so I preferred not to volunteer. Much later I learned that the life expectancy of those who parachuted into occupied France was about 2 weeks. Once you started broadcasting information on your radio set you would be hunted down by the enemy and eventually captured.

Illustration showing the Graduation Class of Walter Reed General Hospital, June 1944.

The week I completed my training at Walter Reed, the invasion of continental Europe began. It was 6 June 1944. It was supposed to be 5 June but the weathermen told Ike the conditions were poor for a landing so “D-Day” was postponed for another day.

I was sent back from Walter Reed Hospital to Camp Grant, where I became part of the newly formed 164th General Hospital, activated 15 July 1944.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

We were sent by troop train to Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey (Staging Area for the New York Port of Embarkation -ed), to prepare for the journey to Europe. We boarded RMS “Scythia”, part of convoy CU 39, leaving New York and landed at Cherbourg in the Cotentin Peninsula, France approximately two weeks later.

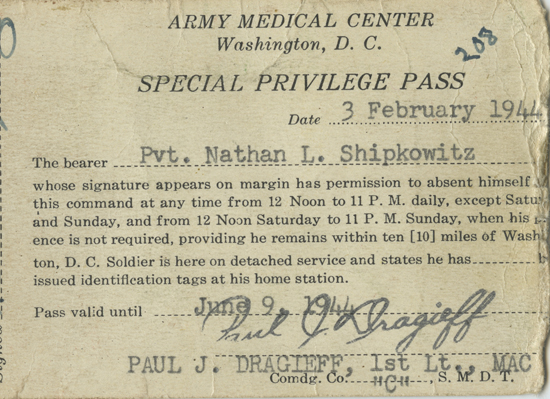

Special Privilege Pass awarded to Nathan Shipkowitz on 3 February 1944. As can be seen, the pass was valid until 9 June 1944.

The ship that took us from the United States, RMS “Scythia”, was owned by the Cunard Line of Great Britain which transported over 2 million servicemen. The Cunard Line also owned the “Queen Mary”, the “Queen Elizabeth”, the “Mauretania”, and the “Aquitania”. Those 4 large express liners were extensively used during World War 2. I saw a photograph of the Scythia – actually, a painting that was based on a photograph of this ship. The flag at the top of the mast was the British Union Jack. The trip from the United States to France took thirteen days. On the last day when we could see the shores of France, the captain brought down the tattered flag and ran up a brand new British flag.

Trans-Atlantic Crossing:

The trip across the Atlantic was not free of danger. The first day of the trip, the captain announced a drill for “General Quarters” and “Prepare to Abandon Ship”. All the soldiers on board had to leave their quarters. I was in “D” deck, or four decks below. You had to run up the narrow staircase wearing your Mae West life jacket that had a single cell flashlight attached to a shoulder lanyard. When “D” Deck was vacated, “C” deck started up the stairs. This went on until all the troops were on deck and in their assigned space. When I got to the top deck a seaman yelled at me: “Soldier, where is your helmet? Go back and get your helmet”. So I had to run down the stairs to “D” deck to get my helmet. The traffic was all going up and I was going down. I retrieved my helmet and got back on deck. My assigned place near our lifeboat was next to an anti-aircraft machine gun that was welded to the side of the ship. Three British sailors manned the gun. The gunner sat in a little cage attached to the side of the ship. An ammunition loader stood nearby and he fed the belt with bullets to the gunner. A third sailor was a runner. He carried the ammunition belts from the storage locker. A balloon target was cut loose and the gunners began firing at the target. After about a half hour, the captain said, “All Clear, return to your quarters”.

I often thought of the fact that I couldn’t swim, when we crossed the Atlantic Ocean chased by German submarines, remember I might have joined the Navy…

About the third or fourth day out there, there must have been a German submarine in the area. Our troop ship was surrounded by American destroyers. The destroyers started dropping charges. These were large cylindrical barrel-shaped drums containing TNT. They were projected overboard. The depth charges were fitted with a fuze set to go off at a pre-determined depth (they usually contained 200 lbs of Torpex and depth settings up to 600, and later up to 1,000 feet -ed). A submarine did not have to take a direct hit. The shock waves would cause damage to crew and equipment inside the submarine if detonated close enough. Additional charges and subsequent shock waves could cause hull breach or fissures and disable the sub.

The Navy depth charges started exploding at supper time when we were below deck. All the lights on our ship went out. The giant ocean liner that we were on rocked like a toy boat in a bathtub. After about a half hour the depth charges stopped.

Group of Medical/Surgical Officers pertaining to the 164th General Hospital, during its stay in France. The second person on the right is 1st Lieutenant William E. Sheffield. Courtesy Robert Sheffield

Our ship was double-loaded. There were twice as many troops on board as there were accommodations. We slept in hammocks that were about 18 inches apart. Every other night you could sleep in the hammock. The other person assigned to this place took over for one night. Sinks and showers on the ship operated with seawater. Special hard water soap was provided but after washing or taking a shower your body was coated with salt.

The ship’s boilers needed fresh water to make steam to drive the engines. Fresh distilled water was provided to the cooks. The side of the ship had pipes that contained fresh drinking water. The fresh water spigots were locked with a padlock. The master of arms unlocked the water spigots for one hour twice a day. You could then fill your 1-quart canteen at this pipe. We were told to keep our canteens full at all times because if ever we had to abandon ship that canteen of water would mean the difference between life and death.

France:

When we finally reached Cherbourg harbor, in the Cotentin Peninsula, France, the ship’s engines stopped. Two men in a row boat slowly moved from shore to our ship. When the boat reached our ship, one man climbed up the rope ladder and the other man returned to shore. The man who came aboard was a pilot. The harbor was mined to keep Allied ships or submarines away and to protect the installations. Several hours after the pilot came aboard the ship engines started. Our boat would weave its way through the water. The plan was to get us as close as possible to the shore and then off the ship onto land. This very slow movement – with weaving and back-ups continued for about a day. Then our ship’s engines stopped. We had arrived and were as close to land as the ship could go.

View of Rhino ferry and tug, operating off the shores of Normandy. Picture taken 6-7 June 1944.

Cargo nets were dropped. The troops were told to prepare for disembarking. We were given 3-days of food. These were “K” Rations, including D-bars, dehydrated food, and candy snacks.

“Rhino” ferries were in the water. We would continue our movement on such a platform to reach the coast.

Lt. Colonel Frederick S. Harrell, our Commanding Officer, was standing next to the First Sergeant. He would call your name, and you had to answer with your ASN (Army Serial Number). You then climbed over the side of the ship, got a solid hold of the cargo net and slowly lowered yourself to the raft. You had a full haversack, steel helmet, and a duffel bag. Once you were on the raft you were lined up in order. You sat on your duffel bag until everyone was accounted for. Attached to the Rhino ferry was a small tug boat flying an American flag, this was a U. S. Coast Guard Landing Craft, Support, with a crew of two. One sailor piloted the craft – while the second one stood ready with a prong to pull you out of the water if you fell off the tug.

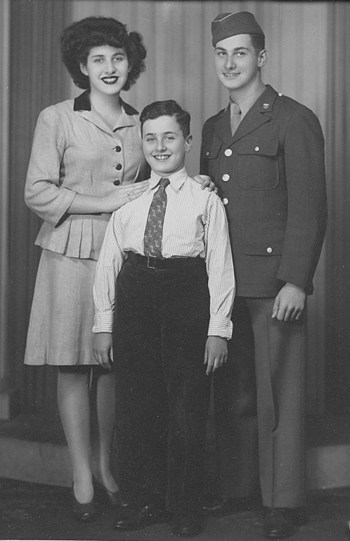

Nathan whilst on leave is pictured with his sister Libby, and brother Irving.

The Coast Guard pulled us through the water to the French coast of Normandy. Then as we approached shore the tug turned around. Instead of pulling us on this Rhino – it turned the raft around – and began pushing us to shore. Finally you could hear one engine rev up and the landing craft gave the platform a final big push and then cut us loose. The Rhino just floated in. We were almost on shore. I jumped off into about 3 feet of water pulling my duffel bag behind me. Our Sergeant told us to look for the Beachmaster – wearing a steel helmet with appropriate markings. Our B.M. was no. 34. He would tell us about our next move.

Our group assembled around the B.M. He said we would be picked up by military trucks later. The trucks arrived 4 or 5 hours later. About 10 soldiers got into the open trucks. We carried our haversacks, intrenching tool and duffel bag. We drove most of the night through little towns that were completely deserted. Houses, churches, schools were all showing signs of destruction. By morning we arrived at the site where we would start setting up our 164th General Hospital in a little town near La Haye-du-Puits.

This was hedgerow country. The hedgerows were perimeters of land that were cleared in the center for crops or for grazing cattle. The hedgerows were about 5 or 6 feet high. They kept the cows localized and separated the different pastures.

Once here we started putting up the hospital tents which were to form the 164th General Hospital under command of Lt. Colonel F. S. Harrell, MC, O-28561.

The area around La Haye-du-Puits (Bolleville) where we set up was hedgerow country. All personnel slept in pup tents, that is, 2 soldiers per tent. Each soldier was issued one shelter-half. Two halves properly assembled made a complete tent. We were provided with a single blanket per person. So, two people in a tent, one blanket for a mattress and one blanket for a cover. We slept with our clothes on as nights were cool. We put our raincoats on the ground and one blanket on top of that for a mattress. The Sergeant instructed us to set up our tents parallel to the hedgerows, not perpendicular. The reason was that if the German Luftwaffe was on a mission we would be protected by the hedgerows. They also protected us from wind and rain.

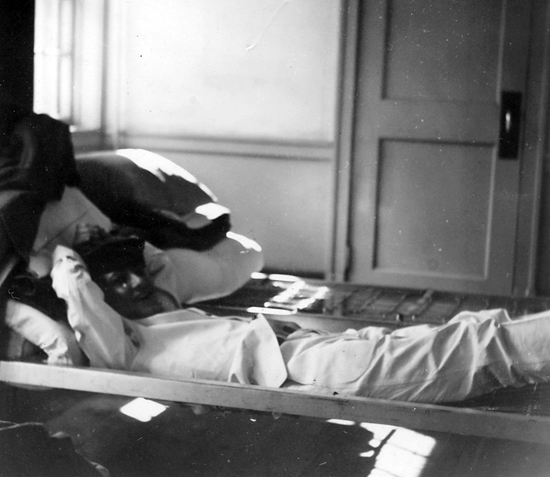

Photograph of Nathan during a break at the Walter Reed General Hospital.

During the initial D-Day assault phase, paratroops were dropped. Some of these soldiers got hung up in trees and had to cut the parachute shroudlines and climb down the tree. I saw a parachute canopy and thought it would make a nice scarf. But it was pretty high up in a tree so I forgot about obtaining a souvenir scarf for free.

The Corps of Engineers arrived with drinking water. The water was pumped into Lyster bags, capacity about 25 gallons. A disinfectant, liquid chlorine, was added to the water and it was safe to drink after about 1 hour of treatment. It tasted like chlorinated swimming pool water. The Lyster Bag was often used to provide water for cooking, showers, and medical use. Every day ward tents, pyramidal tents and medical equipment kept arriving. This was the beginning of our Hospital. We set up tents, moved in beds and most of all, small pot-bellied stoves were delivered which burned coal or wood. They did help to keep the tent warm and dry.

Next, folding canvas cots arrived so we no longer had to sleep on the ground. Food was trucked in daily. We had enough to eat but it was hardly a banquet. As time went on, we could count on three hot meals a day. Oatmeal for breakfast, powdered eggs for dinner and hamburgers for supper.

After about 3 weeks of preparation, casualties started arriving. We were a second or third echelon medical facility. Our Operating Rooms were set up in two Quonset huts. Four tables per hut – for a total of eight operating tables. Each table had an operating light alongside. Generators were provided to supply electricity for the lights. There were enough casualties so that eight cases at a time were operated on. Mostly the surgeons had to remove shrapnel or bullets, and subsequently close the wound. I would assist the surgeons and if I could, I would take the bullet or shrapnel from the patient and wrap it into a piece of gauze. Then I would tape the gauze to an arm or leg. I thought when the casualty awoke and looked inside the gauze he would have a ‘special’ souvenir to take home. The casualties were moved to a ward tent waiting for air evacuation to England. If the weather permitted there would be several flights a week to England.

Cases of Trench Foot are gradually increasing in the European Theater.

During fall and winter some Trench Foot cases were observed on incoming patients. Prolonged exposure of the feet to moisture and cold was causing affected parts to itch and burn with numbness and tingling in the toes. Blood circulation slowed down, blisters appeared and got infected, and gangrene could develop, causing amputation. Orders were given to change wet socks every day. A supply of wool socks was sent in daily. The used ones were burned and never used again.

Notwithstanding the successful D-Day landings, the Germans still occupied Jersey and Guernsey (Channel Islands, liberated 9 May 1945 -ed) where they built pillboxes, coastal defenses, an underground hospital, a weather station and observation posts. They broadcast information back to the Nazis about Allied troop movements in the Channel between England and France. About the time the Wehrmacht was being routed, a landing party of Germans broke through the Allied naval blockade and attacked the shores of France. They came ashore on a Saturday night and raided Granville. Some of our Officers were having a party when the raid was on. Everyone, including some Army Nurses who were also present, was told to stay indoors while the raiding party was being searched for.

When the surgery schedule slowed down, I was given the job of treating the patients with a new drug. The powdered drug was in a vial; add sterile saline, and it turned golden yellow. The name of this new drug was Penicillin. I had a list of patients that I visited every 4 hours to give them an injection of penicillin. The patients were in hospital ward tents, about 10 patients per tent. I had a flashlight and gave the injections of penicillin after first identifying the patient by name and then using the flashlight to check the name tag at the foot of the bed. Since this was a 4-hour shift, if I hurried I could finish my rounds early. I would then get into a hospital bed for 1 or 2 hours of sleep. I kept looking at my wristwatch that had a luminous dial to avoid oversleeping.

Photograph showing four members of the 164th General Hospital. Crouching in the foreground is Nathan Shipkowitz.

Some time after the hospital had been in operation, we were assigned a contingent of German PWs. They did manual work and were quartered in our hospital area, under the watchful eyes of the American personnel. The German prisoners would move patients from the tents to the O.R. and back. Instead of carrying them, they transported them on collapsible litter carriers which could easily be moved by one or two men. Two prisoners could move a patient instead of the four that it usually took to carry a patient on a standard litter. One day I overheard a conversation among some PWs. As I could understand a little German and I knew the word “Volkswagen” meant People’s Car, I asked one of the PWs what was going on. He told me that after Hitler came to power, he planned an investment program to build a car for the people, one car for every worker in Germany. There was an advertising campaign to encourage people to save 5 Reichsmark a week to fund their own car. None of the vehicles were ever delivered as the war prevented large-scale production, and manufacturing shifted to full production of military vehicles. This was sort of an inside joke to the Germans, but it wasn’t funny because the prisoners said they would never get a car and the money they saved was lost. They were discussing the irony of the situation; instead of driving one of the new cars promised by Hitler, they were pushing litter carriers as prisoners of war!

We were permitted to treat non-combatants. During our first winter, a French civilian woman appeared at the Hospital for help. She was pregnant. One of our doctors, an obstetrician (Dr. Popkin) said the baby could come any time. We were not equipped for this type of medical emergency but it was decided to help this woman since there was no place else she could go. We prepared to deliver the baby. The German prisoners that did carpentry work built a crib for this baby that was supposed to come. On Christmas Eve, the baby was born. The German prisoners began singing, ‘Stille Nacht’, ‘Heilige Nacht’, (Silent Night, Holy Night). This was the most memorable Christmas I ever had in my life.

One day when I was on duty, a French casualty arrived. It was a farm kid about 14 years old who had been looking for a lost cow. The cow wandered away and this kid stepped on a land mine. His mother was with him. The surgeon told me to remove his clothes so he could see the extent of his injuries. I had been told: ”Just cut the clothes off, so as not to disturb the injury”. I started to cut the clothes when the kid’s mother started gesturing wildly, and kept saying: “Non, non”. She obviously did not want me to cut the clothes. She wanted the pants and sweater that he was wearing. Warm clothing was indeed hard to get so I carefully removed the boy’s clothes so that the surgeon could see what was broken or if there was any hemorrhage.

When the war in Europe finally ended and General D. D. Eisenhower made arrangements to accept the German unconditional surrender, the 164th General Hospital no longer had a job. But, the war in the Far East was still on. We were told that we would be moving from Normandy to Marseille, Southern France, to deploy to the Pacific Theater to finish the war against Japan.

Redeployment:

When moving from La Haye-du-Puits to Marseille, Southern France, we were transported in French railroad boxcars. There were about 25 or 30 soldiers per car. The side of each car had 40/8 painted on its side. During WW1 these cars were widely used to transport either 40 soldiers and/or 8 horses to pull artillery guns. This notation became famous because there was actually a fraternity formed within the American Legion (in 1920) in the United States designated “La Société des Quarante Hommes et Huit Chevaux” (Association of Forty Men and Eight Horses). These infamous boxcars were again used to transport troops to and from the front in World War 2.

Filling of a Lyster Bag. Picture taken in the Zone of Interior, 1941-1942.

The boxcars slowly moved from Normandy to Southern France – Marseille. I saw the Eiffel Tower when we passed through Paris. The crew would stop every couple of hours so we could get out and stretch our legs. We ate rations and drank water out of our canteens for the entire trip. After reaching the outskirts of Paris we pulled up next to another train on an adjoining track. I saw a huge wooden barrel on a flat car next to our train. We waited while the engineer took on water. The barrel was labeled, vin rouge (red wine). I thought this would be a real treat so I tried to loosen the spigot. I couldn’t do it. One of my friends said: “Use your intrenching tool” so I took my shovel and pounded on the plug until it got loose. The wine started flowing. I took off my helmet and filled it with wine. Pretty soon everyone on the train was running to fill their helmet with red wine. The train crew finally saw what was going on and they rushed over to stop the flow of wine. That was the best part of the trip. After about 4 or 5 days on the train, we finally arrived in Marseille.

When we got to Marseille we turned our winter uniforms in and received summer khakis because we would be going to the tropics. While we were waiting at the old port to get on the ship to take us away (USAT “General Morton”) there was an announcement that President Harry Truman (who succeeded FDR as U.S. President) gave the order to drop the A-bomb on Hiroshima, Japan (“Little Boy” 6 August 1945 -ed). A second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki (“Fat Man” 9 August 1945 -ed). Harry Truman was told by Professor Einstein and Dr. Teller not to drop the bomb. They told Truman that the radiation from the bomb would be so severe it would make the area in Japan radioactive for 100 years. Harry Truman’s response was the Japanese should have thought of this when they bombed Pearl Harbor.

Home:

This all happened while we were in Marseille, waiting to redeploy to the Far East. But there was confusion. The rumor was that the war with Japan would soon be over and the captain of the ship was told to wait in the harbor for further orders. After 3 or 4 weeks of waiting, we were finally told that our ship, instead of going to the Far East, would be going back home to the United States. We boarded the ship in Marseille on 23 August 1945 and headed for the Zone of Interior.

We went through the Mediterranean and into the Atlantic. One of the soldiers, a friend of mine (Private McDougal), about the second day out in the Atlantic, was so happy that he was going home, that he took his duffel bag and threw it overboard. Then he removed his dog tags and threw them into the water also. He said maybe someone will catch a fish that has my Dog Tags and will say: “Here’s a fish with Dog Tags. And here’s McDougal”. One of the Officers on the ship saw it happen and he sent 2 MPs to put the man under arrest. He spent the rest of the trip in the brig and was fined for the cost of the clothing that was contained in the duffel bag.

We reached Newport News, Virginia on 2 September 1945 and after disembarking, were given a 2-week furlough. The Army began discharging the soldiers as soon as they practically could. This was the end of the war for all of us, and the end of the 164th General Hospital’s mission.

The MRC staff is particularly indebted to Tec 5 Nathan L. Shipkowitz (ASN: 36679423) who served as a Surgical Technician with the 164th General Hospital in the European Theater of Operations for sharing his personal reminiscences with them. On 7 April 1946, Tec 5 N. Shipkowitz was honorably discharged at Cp. Grant, Illinois.