Veteran’s Testimony – Philip J. Morrison 24th Evacuation Hospital

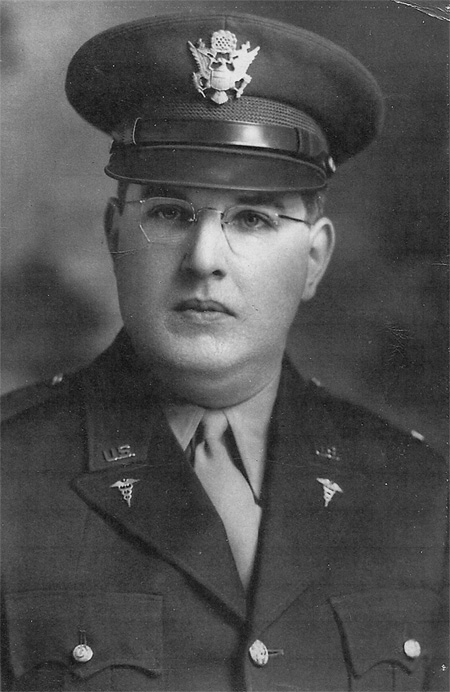

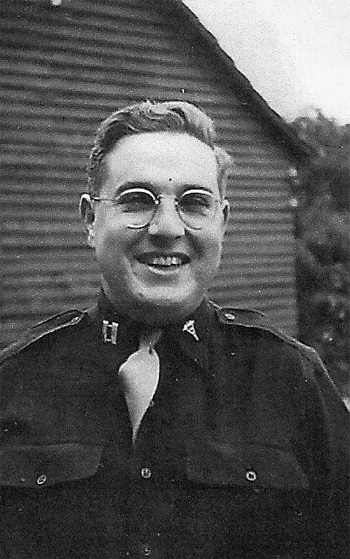

Portrait of First Lieutenant Philip J. Morrison, MC, O-1685862 (1910-1987).

Introduction:

Dr. Philip J. Morrison was a native of Nashua, New Hampshire, where he was born 22 April 1910. His parents were John L. Morrison and Josephine F. Sullivan. After attending Grammar School for 8 years, he went to High School where he followed courses during another 4 years. Philip Morrison then went to the Holy Cross College, Worcester, Massachusetts (one of the oldest Catholic colleges in New England –ed) where he graduated in 1931 with an AB. Following College he worked as a Research Associate in the Department of Research Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School from 1931-1935. He then went to Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, in 1935. Dr. Morrison was an Oxford Research Fellow from 1938 to 1939 and he graduated 4th of his class in 1939.

On 16 October 1940, Dr. Philip J. Morrison, was officially registered in accordance with the Selective Service Proclamation of the President of the United States.

Review and parade of the 24th Evacuation Hospital while at Camp Tyson, Paris, Tennessee. Photograph taken October-November 1943.

He was Assistant Surgeon at the Harvard University Employees Clinic and a Graduate Assistant on the Surgical Staff at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, 1941-1942 (the latter assisted in establishing the affiliated 6th General Hospital, activated 15 May 1942, which embarked for North Africa on 7 February 1943 –ed).

His internship was served at the Mercy Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, after which he became Chief Resident Surgeon at York Hospital, Pennsylvania. Dr. Morrison married Mabel C. Miller (a Nurse) in Baltimore 14 February 1942 (they both worked at Mercy Hospital at the time). He served a Fellowship with Dr. Robert Linton, at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which ended in July 1942.

First Assignment:

Dr. Philip Joseph Morrison was temporarily appointed and commissioned in the Army of the United States as a First Lieutenant, effective 1 June 1942, with Army Serial Number O-1685862 and Military Occupational Specialty and Number Surgeon General 3150. Dr. P. J. Morrison entered active duty in the Army of the United States on 4 July 1942 (a ‘special’ date or a mere ‘coincidence’ –ed), and at his Induction Station, Camp Edwards, Falmouth, Massachusetts (Antiaircraft Artillery Training Center –ed) he joined and was assigned to the 26th “Yankee” Infantry Division (Massachusetts National Guard unit, inducted into Federal service 16 January 1941), with which he got his first taste of the Army.

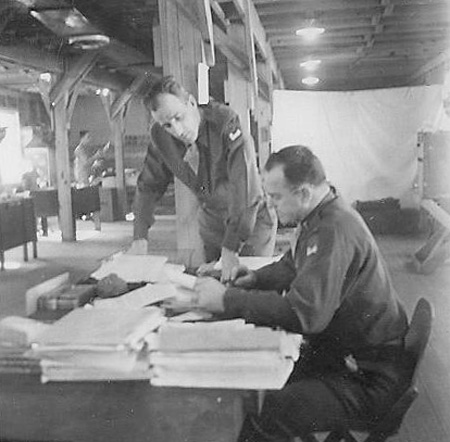

Administration and paperwork. 24th Evacuation Hospital Officers at work at Camp Tyson, Paris, Tennessee, end September 1943.

His unit was almost constantly on the move, leaving by motor convoy from Camp Edwards to A.P. Hill Military Reservation, Fredericksburg, Virginia (Maneuver Area), which it reached on 10 July, 1942. Lieutenant Morrison then spent 4 weeks at Carlisle Barracks, Medical Field Service School, Pennsylvania (1 October-1 November) before rejoining his outfit at Fort DuPont, Delaware (Mobilization Station) on 10 November 1942. The 26th Infantry Division remained at this location until 3 January 1943, when it received orders to transfer to Fort Jackson, Columbia, South Carolina (Infantry Training Center), where it arrived 27 January 1943. A special celebration took place in February when a first child (daughter) was born, with Mother and daughter eventually joining Lieutenant Morrison at Fort Jackson on 5 April, where they moved into the married quarters. The next move brought the Division to Camp Gordon, Augusta, Georgia (Division Camp) on 18 April 1943, where it would be stationed until end of August 1943 (First Lieutenant P. J. Morrison was to leave the post 29 May 1943 for a new assignment –ed).

Final Assignment:

On 30 May 1943, Captain P. J. Morrison joined the 24th Evacuation Hospital (activated 15 June 1942 at Ft. Custer, Battle Creek, Michigan –ed) at Camp Blanding, Starke, Florida (Infantry Replacement Training Center –ed), the organization with which he was to participate in the Tennessee Maneuvers.

He wasn’t the only person to join the organization, as more Enlisted personnel were assigned to the unit while at Camp Blanding. It was here that he would spend his first Christmas and away from home. The traditional tree had been planted in the sand complete with all its trimmings, adding a touch of unreal atmosphere to the occasion. Early January 1943, everyone was to find out that cold weather also came to Florida, particularly during overnight bivouacs with blackout measures and no fires to keep warm. The only method to keep warm was to play football since there wasn’t much to do. This month also saw several more new Officers join the 24th.

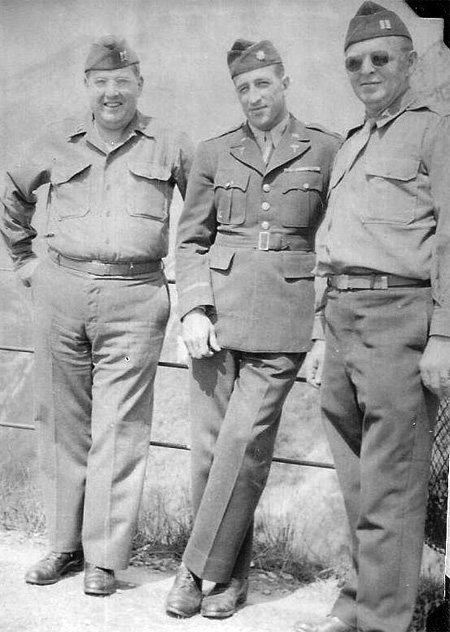

Captain P. J. Morrison (left) with Lieutenant Colonel Carl M. Rylander, CO 24th Evacuation Hospital (middle) and another fellow Officer. Photo taken in the Zone of Interior.

Training:

The training fully occupied everyone and week-end passes were never neglected to such thriving towns as Starke, including Jacksonville, St. Augustine, and occasionally Daytona, which also received some attention. With the warm weather coming up once again in early spring, good use was made of the lake that surrounded the camp and the swimming was really refreshing, especially after a long hike.

The last days spent at Camp Blanding proved to be busy ones, as the organization was to go on Maneuvers and the entire personnel got busy packing supplies, identifying and marking crates, and loading boxcars. New Officers kept on joining the outfit. All the Enlisted Technicians had meanwhile returned from their respective Schools and the last few nights were extremely hard on everyone as all the married men were busy packing up their wives’ belongings and getting them ready to return home before taking off for the wilds of Tennessee.

Captain Philip J. Morrison, removing a patient’s appendix, with Major Wallace H. Graham assisting. 24th Evacuation Hospital, September 1943.

With June 1943 almost closing, the first phase of the 24th Evac’s training ended with the organization now leaving for Maneuvers, one year after its activation. On 13 June, the unit left Camp Blanding and basic training for Tennessee and something much different from daily Army life: Maneuvers! With all equipment carefully packed and loaded and the organization’s vehicles securely fastened to the little flatcars, the 24th rolled northward through Georgia, stopping nearly around midnight at Portland, Tennessee, where it detrained. The necessary details were chosen to unload equipment and vehicles, and after spending a sleepless night, everyone was hustled off to the selected bivouac area. The necessary tents were pitched and made secure against any possible ravages of rodents, nature, or the elements. Several nights later, when the rains came, all the men realized that there was still much to learn about setting up in the field correctly.

While at the Maneuver area, the 24th Evac Hosp welcomed its first contingent of 19 ANC Officers, under the guidance of First Lieutenant Alice Ensor (later to be appointed Chief Nurse –ed). Their first impression of the wilderness they had arrived at certainly produced visions of the pioneer women that blazed the local trails many years before.

The first ward tents were set up beneath some trees on the hillsides near Castillian Springs on 2 July 1943, and as from 1400 hours, the first patients started coming in, reaching a total of 182 after only three days of operation. On 12 July, the organization moved to a new site, just west of Westmoreland to a hamlet with the romantic name of Liberty in a complete different setting with lots of undergrowth which required laborious clearing before being able to pitch any tentage. The advantage was that the surroundings not only provided the necessary camouflage for the installation but some cool refuge from the summer temperature. 25 August 1943 brought another move to a new installation site, one of the last, in the vicinity of Gallatin, which proved a most pleasant area to set up. After some passes and furloughs, the very last move brought the unit to Lebanon, where the hospital was established in some neat rows across a green pasture, while the personnel pitched their tents among the many cedar tress.

On 18 September 1943, the 24th bade farewell to the wilds of Tennessee and entrucked for Camp Tyson, near Paris, where they would become familiar with the many silver-colored high soaring Barrage Balloons. The PX and its supply of beer and coke were a most welcome sight after having spent almost three months of Maneuvers living in very humble conditions.

Left: Photograph of Captain P. J. Morrison taken while staging at Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey (Staging Area for New York Port of Embarkation). The 24th Evacuation Hospital remained at Camp Kilmer from 14 to 21 January 1944.

Right: Lineup of tents at Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey.

Movement Overseas:

It was at Camp Tyson, Tennessee, that preparations for an eventual overseas movement were begun. The unit waited and wondered what was in store for them, as October and November 1943 passed on. Meanwhile, furloughs and passes were given and a kind of regular garrison life rolled on. In December of 1943 activities suddenly increased, and extra equipment distribution, physical inspection, immunization shots, infiltration course, forced marches, extra courses and lectures, followed each other without mercy, including extra paperwork for Officers and Noncoms. Headquarters became a beehive of activity as everyone got ready for the forthcoming crossing of the Atlantic.

The afternoon of 10 January 1944 found the group of Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men assembled at the small railway station of Camp Tyson. The careful preparation in view of the expected move was over. A small band played while staff and personnel boarded the waiting train on its way east, traveling via Louisville, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Washington DC, Philadelphia, finally reaching Camp Kilmer, Stelton, in New Jersey, the final Staging Area for the New York Port of Embarkation, on 14 January.

Processing: would this be the final one ? The inevitable procedure applying to all troops making ready for some important move was started. Inspections, followed by physical examinations and some more immunization shots, apparently the last ones, and some passes to New York City, filled the 7 days of staging at Camp Kilmer.

Following a monotonous crossing by ferry across the river to the boarding dock, the 24th left the ferry with a band playing, civilians looking on, and ARC girls handing out welcome coffee and donuts down the lines of waiting soldiers.

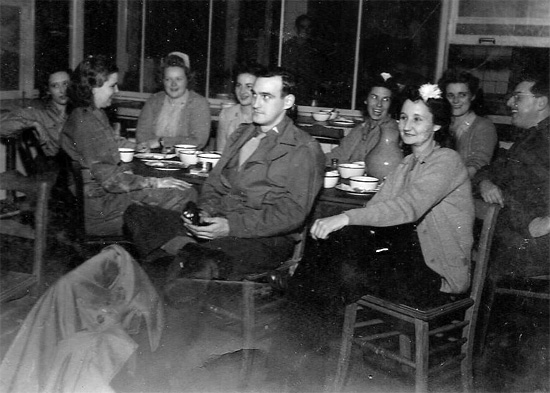

Officers and Nurses of the 24th Evacuation Hospital, in the Officers’ Mess somewhere in France … Dr. P. J. Morrison is the last person on the right.

United Kingdom:

The unit boarded the “Queen Mary” around midnight, 21 January, and with everyone safely set up, Officers and Nurses in separate state rooms, and Enlisted Men down her lower decks, she was ready to set sail for the Atlantic and the old continent. The “Queen Mary” converted into a troop transport had an enormous capacity and would sail the seas throughout World War Two and even after the conflict (her ballroom had been turned into a huge mess hall). The maximum number of troops ever carried was 15,740 + a 943-man crew (25 July 1943); she even once transported the entire 1st Infantry Division, involving 15,125 men on 2 August 1942. She also had the privilege of carrying VIPs, such as British PM Winston Churchill, and brought back GI war brides and children to the United States and Canada as well as transferring over 5,000 German PWs to the Zone of Interior.

The huge ship departed New York harbor 22 January 1944 heading for the vast Atlantic. Apart from the daily routine, abandon ship and lifeboat drills, anti-air raids exercises and anti-submarine watches, dispensary details, and adapting to English food (supplemented by PX purchases), it proved a struggle to maintain some sort of equilibrium while exploring the maze of hallways and corridors of the huge vessel. Some became seasick, others adapted more easily. Rumors abounded of enemy subs hunting for a prey, hence the zigzag motion of the ship, of enemy airplanes lurking, and the crew’s regular antiaircraft fire drills.

During the night of 28 January, the ship’s master announced over the PA system that the coast was near and informed everyone aboard that the Queen was now entering the Firth of Clyde, signifying the end of the journey.

The morning of 29 January 1944, almost everyone was on deck discovering the landscape of Scotland and the village of Greenock where debarkation would take place. Small boats shuttled the passengers to shore. Once on land, some regrouping took place, followed by instructions, and by a quick march to a waiting train. After drawing the blackout shades and making certain all personnel and individual gear were accounted for, the train departed with destination England where the 24th would remain for a number of months. Along the way and after reaching Cheddar station, the men were confronted with bombed towns in war-torn England, so far they had only known about the cheese!

Left: Medical Officers of the 24th Evacuation Hospital (Capt. P. J. Morrison is the fifth person on the right). Picture taken in the European Theater, location unknown.

Right: Medical Corps and Army Nurse Corps Officers of the 24th Evacuation Hospital in the ETO (Capt. P. J. Morrison is the fourth person from the left).

The first few days were spent in getting settled and acquainted with the surroundings and its people. At the time, everyone thought the hardest thing about the country was its complex money and it took weeks before the 24th realized that 1.00 British Pound Sterling equaled 4.00 US Dollars. For those used to whiskey, it was clear that Scotch was not Bourbon, it was watered. Blackout was special, and for many it caused wet pants in the creek, and running into walls when returning to base. Listening to sirens, aircraft sounds, and guns blazing, made the men soon realize that there was a war going on!

When spring finally broke through, there were frequent bike rides in the country and lots of stops at the pubs, bus rides into bombed-out Bristol, and softball and baseball games on the rearranged playgrounds. But not all activities were that pleasant. Showdown inspections, constructing crates, learning how to pack and unpack trucks, pitching and wiring tents, preparing camouflage material, followed or interrupted by calisthenics and road marches. By late spring, trucks, equipment, and men were ready, and everyone was wondering when would the move to the continent take place …?

France:

For the past days staff and personnel had been listening to the radio bringing details of the long-awaited invasion of the continent and the assault against Fortress “Europe”. The air was tense, for on the morning of 8 June 1944, the 24th Evac marched in the rain through Cheddar to the railway station. The train ride was uneventful and the first part of the destination was reached by mid afternoon; from where trucks were boarded and the men continued their journey to the marshaling area in Truro, situated on England’s southern coast. The following day, 9 June, the organization was taken to Falmouth harbor where a final roll call took place. At the crucial moment, the men loaded with packs and duffel bags were all marched to the pier where they waited for transportation to France.

It was a relief to finally board the “Francis Drake” Liberty Ship, but a disappointment to discover the poor sleeping and living accommodations once inside the vessel. Sleeping in shifts became a necessity due to the lack of proper individual space (triple bunks). The Officers and Nurses had no better deal, they too had to endure the hardships.

The latrine, situated on the main deck, consisted of a trough, a bucket, a water hose, and a stretch of canvas. Boarding took place around 2100, 9 June, but the ship didn’t sail before 0200, 11 June 1944. Being part of a convoy set for France, breakfast was served on board at 0500 the next morning, without being bothered by the Luftwaffe. When the “Francis Drake” hoisted anchor, the anti-submarine nets opened in the harbor and the ship steamed into the English Channel to rendezvous with the rest of the convoy. Allied aircraft zoomed overhead and escort ships dropped a few depth charges, just in case. After another restless night, the ship reached its destination, Normandy, anchoring off the French coast. This was 12 June 1944. Numerous ships stretched far away beyond the horizon, the sky was filled with barrage balloons, and distant inland gunfire was clearly audible. Towards dusk, an LCT pulled alongside the “Francis Drake” and the surgical section and 3 trucks were loaded onto the landing barge which then made for Omaha Beach which it reached at abut 2300 hours (included were the 18 Nurses from the 51st Fld Hosp who had joined the organization for the Channel crossing –ed). As night fell, the group proceeded toward their objective atop a hill inland, located behind Green Beach, near Englesqueville, where they were to lend a hand in support of the 1st Hospitalization Unit, 51st Field Hospital (which landed 8 June and set up their installation on 11 June 1944 –ed).

For the next two days, the section worked almost constantly with an occasional hour of sleep on the ground, accompanied by the roar and violence of enemy bombings and American antiaircraft fire. On the morning of 14 June 1944 the detached group joined the parent unit at La Cambe which had disembarked the day before to set up its own operation.

The Commanding Officer, assisted by some Officers already traveled a few more miles into the interior where the advance party (landed on 7 June 1944 –ed) had commenced setting up the hospital near La Cambe, which began its first ‘combat’ operation at 1500 hours. Officers and Nurses of the 45th Evacuation Hospital who were waiting to set up their own unit assisted the unit at the beginning. Lots of recollections would remain vivid with the veterans of the 24th Evac long after the war, such as the friendly and enemy fighters buzzing the hospital tents almost on a daily basis, the nightly raids by the Germans that kept everyone wide awake, the intensive ack-ack and colorful tracers that resembled premature 4th of July celebrations, and certainly the severe storm that hit Omaha Beach on 19 June 1944, the worst one in 40 years, raging for three days, which wrecked the artificial harbor. Other memories would include the lack of fresh rations, the abundance of apple cider, the introduction to calvados, the very first shower bath, the relationship and camaraderie with members of the 2d Evacuation Hospital, the 4th Convalescent Hospital, and the 10th Medical Laboratory, and beyond that what swell fighters were those men serving with the 2d, 29th, 30th Infantry and 101st Airborne Divisions, not to forget the 2d Armored Division.

Operations at La Cambe (14 June 1944 > 27 June 1944)

429 operations performed – 518 patients x-rayed

Operations at L’Epinay-Tesson (8 July 1944 > 3 August 1944)

2007 operations performed – 2014 patients x-rayed

Operations at Percy (6 August 1944 > 20 August 1944)

802 operations performed – 894 patients x-rayed

On 8 July 1944, the hospital moved to a large field nearby L’Epinay-Tesson in the rain. Operations closed on 2 August 1944, after experiencing nerve-grinding work. Receiving handled nearly 3000 cases with an overall mortality of 2.5%. During admissions, the war continued outside the wards and operating rooms, with days and nights filled with artillery thunder and frequent calls by enemy bombers during the night. High brass started visiting the installations, headed by General “Monty”, Brigadier General Norman T. Kirk, Major General Paul R. Hawley, and Officers of the Medical Corps.

Tragedy struck when a German bomber hit a Reinforcement Depot, resulting in many men killed that the 24th had recently returned to duty and many more being readmitted for treatment. With the front steadily advancing, the organization moved to a new site near Percy. The men had to proceed through the ruins of St. Lô to reach the new location, but although the days remained busy, it was clear that the Army was moving away from the Hospital very rapidly, thus increasing transportation and evacuation time. The unit handled over 1200 cases during August with a mortality rate of 1.97%.

On 22 August 1944 the longest convoy trip took place; this time it went to a rest area (in fact a medical unit concentration area –ed) situated in a number of wheatfields near Senonches, France. The motor convoy proceeded through deep forests, rolling green fields, moving through villages and small towns; at first sight very peaceful, yet littered with debris of war, destroyed houses, burned-out tanks, and isolated individual graves. But the French people remained friendly, filled with gratitude, and welcomed their Liberators with gifts of fruits and vegetables, and wine or cider. The long convoy, split up, arrived at Senonches in three parts, the last one bringing in the larger part of the Nurses’ complement, arriving after midnight of 23 August.

After enjoying a welcome break at Senonches, it was back to work. On 7 September 1944, another move took the organization (in different convoys) toward La Capelle, where a cold and miserable night was spent. It was amazing on that particular trip how many trucks with personnel apparently reached La Capelle by way of Paris!

Belgium:

The next day, 9 September 1944, the 24th Evac headed for Dinant, Belgium. It was a beautiful drive along part of the Meuse River and some small villages in the country. After reaching Anhée (near Dinant), Belgium, the function mainly consisted in preparing patients coming in from various Field Hospitals and Clearing Stations for air evacuation. The mission of the Hospital became one of an Air Evacuation Holding Unit. During the first half of September, the organization received almost 2000 admissions, with a mortality rate of 0.94%.

Operations at Anhée (9 September 1944 > 15 September 1944)

496 operations performed – 352 patients x-rayed

Operations at Leopoldsburg (19 September 1944 > 6 October 1944)

1229 operations performed – 1587 patients x-rayed

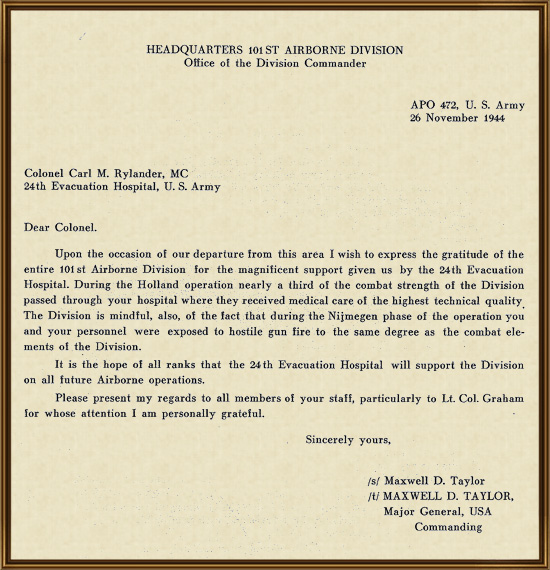

Dinant was left on 17 September 1944 for an unknown destination. Traveling went as far as Louvain, Belgium, the next R-V point, where further instructions were awaited. The 24th Evacuation Hospital was to spend some time on DS to the British Second Army and the mission consisted in medically supporting both the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions in their airborne assault of Holland. The 24th was to be the only American Evacuation Hospital on this mission.

The journey started in daylight, in fog and rain, and finished after dark. Upon arrival at the area (Leopoldsburg, Belgium –ed), everyone made a rush for the tents pitched together in a marshy field. The next day was spent setting up the installation and waiting for casualties. They finally started pouring in Tuesday night, 19 September 1944. As the unit had no Auxiliary Surgical Teams with them, there was a shortage of personnel, and while casualties continued to be admitted in large numbers, additional supplies had to be flown in by cargo planes. Then tragedy struck as a German fighter strafed the Hospital seriously wounding 1st Lieutenant Agatha P. Raus, who was on duty in the OR. The number of casualties diminished after about two weeks and the job looked essentially finished. During their stay at Leopoldsburg, the 24th Evac handled approximately 3500 patients, with a mortality rate of 1.07%, quite a good record.

Holland:

On 8 October 1944, the organization moved into Holland, to set up its installation in a muddy field near Uden. It continued to rain and the abundant adverse weather conditions affected transportation and movement badly. Work was steady during the period but not too heavy. About 900 admissions were registered, 5 deaths were noted, and a mortality rate of 0.6% was achieved. After consolidation of the frontlines in Eastern Holland, the British and American Airborne were now involved in a holding operation. Consequently, the 24th left its site at Uden, for a modern setting in a building situated in the outskirts of the city of Nijmegen.

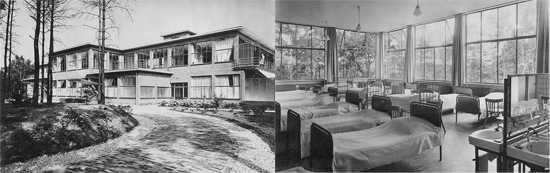

Left: General view of St. Maarten Kliniek (section designated “Orthopaedische Inrichtingen), Hengstdal, Nijmegen, Holland. The 24th Evacuation Hospital stayed in Nijmegen from 27 October 1944 to 2 December 1944.

Right: View of a dormitory at St. Maarten Kliniek (section designated “Paedologisch Instituut”), Hengstdal, Nijmegen, Holland.

Although now being set up in a modern building, the Hospital was rather close to enemy positions. Constant enemy artillery fire was aimed at the area and the Nijmegen bridge, and shrapnel from friendly antiaircraft fire frequently rained down on the installation. Steady detonations and shrapnel played havoc with the many glass windows. And then the inevitable happened; a German shell struck one of the Hospital wards wounding several members of the staff as well as some patients, but fortunately killing no one!

During the 30 odd days in Nijmegen, the unit handled slightly over 1000 patients, with a mortality rate of 1.10%.

In November, the CO was notified that the Hospital was to be assigned to Ninth United States Army, and by 1 December 1944, orders were received to return to St. Truiden, Belgium, for some rest. Before this move, the Nurses and all the patients were evacuated because of the hazardous gun fire. Shortly after it left Nijmegen, several incoming shells damaged the hospital buildings previously occupied by the 24th.

Operations at Uden (9 October 1944 > 26 October 1944)

164 operations performed – 295 patients x-rayed

Operations at Nijmegen (28 October 1944 > 27 November 1944)

331 operations performed – 570 patients x-rayed

Belgium:

Upon arrival in St. Truiden on 2 December 1944, the personnel were billeted in different places, a school, a château, a farm, and a hospital. Although the bad weather persisted and the spreading of the unit was not ideal, everyone enjoyed a period of rest in a ‘live’ town with shops, cafés, and a friendly population.

Germany:

On 19 December 1944 the 24th Evac left St. Truiden, Belgium for a new site, Bardenberg, Germany. This was to be the first move of a Ninth US Army Evacuation Hospital into enemy country! So on it went, through Germany, traversing the Siegfried Line its numerous pillboxes and dragon teeth, moving through the terrible destructions in Aachen, and finally establishing into a modern but battered hospital building in Bardenberg, preparing to support the Army’s drive across the Roer. However, the German counter-offensive in the Belgian Ardennes interrupted all offensive preparations in the sector. After a mere four days, the unit was rushed to Brand instead, where it started operations in some former German barracks on Christmas Eve, 24 December 1944.

Although work was not heavy, with patients coming in from the Ardennes and the Hürtgen Forest fighting, the tension was kept high for several days. Fortunately the weather started improving and the flow of casualties diminished, and New Year was celebrated with high hopes that perhaps the next one would be at home in presence of loved ones… in spite of the severe cold and snow, social life remained pleasant.

Copy of letter of appreciation addressed to the 24th Evacuation Commanding Officer for the support given to the 101st Airborne Division, dated 26 November 1944, and signed by Maj. General Maxwell D. Taylor, CG, 101st A/B Division.

During this period of operation, the organization admitted over 1800 patients with a mortality rate of 1.6%.

Operations at Brand (24 December 1944 > 6 February 1945)

989 operations performed – 2028 patients x-rayed

Operations at Bardenberg (10 February 1945 > 7 March 1945)

1049 operations performed – 1772 patients x-rayed

Operations at Peddenberg (30 March 1945 > 8 April 1945)

751 operations performed – 1032 patients x-rayed

Operations at Esperde (11 April 1945 > 23 April 1945)

409 operations performed – 674 patients x-rayed

Operations at Bremen (21 May 1945 > 27 June 1945)

359 operations performed – 1224 patients x-rayed

On 8 February 1945, the 24th returned to Bardenberg, Germany, officially opening for operations two days later. Following the Allied drive across the Roer, casualties started coming in after the 23d of February. While awaiting the main drive across the Rhine River, the Hospital moved to a small field near Straelen, Germany (this was 7 March 1945 –ed), where they set up tents for a short rest period. Spring was in the air and this gave the men the opportunity to loosen up and play some softball. Passes and trips to Eindhoven (Holland) and München-Gladbach (Germany) were most welcome, and movies and USO shows were organized. On 30 March 1945, the 24th crossed the Rhine and moved into a field near Peddenberg to establish the very first Evacuation Hospital to have crossed the Rhine River.

Casualties were numerous and operating conditions terrible. The heavy rains turned the area into a morass of mud and water. Tents leaked, floors sank away in the mud, and tension rose as everyone was working at top speed. Patients were an array of Displaced Persons, German civilians, German PWs, and American GIs. During a period of only 10 days, the organization treated over 1200 patients with a mortality rate of 2.4%.

Following the Army’s further advance into Germany, the 24th moved ahead rapidly, reaching Esperde, near Hamelin, Germany. The new site at Esperde opened 11 April 1945 and everyone seemed to like the beautiful surrounding countryside. Although being relatively removed from the front line and the sounds of war, casualties nevertheless continued to flow in including quite a number of recently Recovered Allied Prisoners of War from German camps (RAMPs –ed). This was the unit’s first confrontation with these weak, emaciated, and sick soldiers, victims of obvious enemy neglect and maltreatment.

At the end of their stay at Esperde, the organization had handled over 800 casualties, with a mortality rate of 1.23%.

On 30 April 1945, plans called to move across the Elbe River south of Hamburg. But as the city surrendered and hostilities ceased in this area, the 24th instead moved to a field near Stetterdorf for a well-earned rest. On 8 May 1945, the unit received word of V-E Day setting off a very much anticipated celebration by all personnel!

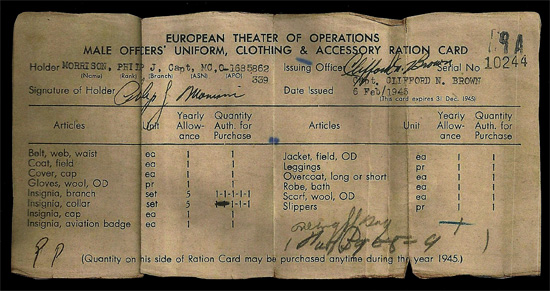

Copy of ETO Ration Card for Male Officers’ Uniform, Clothing, and Accessories, issued 6 February 1945 to Captain Philip J. Morrison, while serving overseas with the 24th Evacuation Hospital.

Everyone enjoyed the many celebrations and miscellaneous activities following the end of the war in Europe. Passes were numerous, sports and games abounded, and the talk of the town was: “when would everyone go home?”

On 20 May 1945, the 24th Evac moved to Bremen, Germany, to operate a hospital in support of the 29th Infantry Division. The new site (buildings) became one the unit’s best areas and setup. The city remained a shambles, but after some cleaning and repairs, the living quarters were comparatively comfortable. There was an athletic field, laundry facilities were available, and German personnel were used for minor work details in the various buildings occupied by the Hospital. During the unit’s stay in Bremen, nearly 1000 admissions were registered, with a mortality rate of 0.96%.

On 29 June 1945, the group was transferred to a field near Erda, where it seemed lost from the rest of the world. Living once more under tentage in cold and rain, the 24th awaited further instructions. On 5 July 1945 a group of Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men with more than 85 points were transferred to the 97th Evacuation Hospital. This day meant the loss of many close friends and comrades. On 18 July 1945, the remaining personnel moved to Ober-Mörlen, Germany, to set up in an apple orchard. This brought the unit within only 5 miles of Bad-Nauheim which possessed a number of recreational facilities such as golf, tennis, swimming, and a theater.

Awaiting and wondering whether it would be transferred to the CBI Theater or not, the Hospital tried to enjoy the fair weather and the many sporting events. When the good news of the surrender of Japan came through, this called for another celebration and a valid reason to give thanks once more. Now everyone would go home for good – the only question still remaining was: “when?”

Even tough the war was over now, the organization moved into a school building in the town of Rotenburg, near Kassel, Germany. The trip took place on 27 August, and upon arrival, the unit relieved the 44th Evacuation Hospital absorbing their patients. Rotenburg was the place where everyone expected to be told when to return home to the Zone of Interior; Meanwhile the 24th Evac continued to watch over and care for its flock of approximately 50 patients…

On 3 October 1945 the 24th Evacuation Hospital was informed by Ninth United States Army Headquarters that it had been awarded the “Meritorious Service Unit Plaque”.

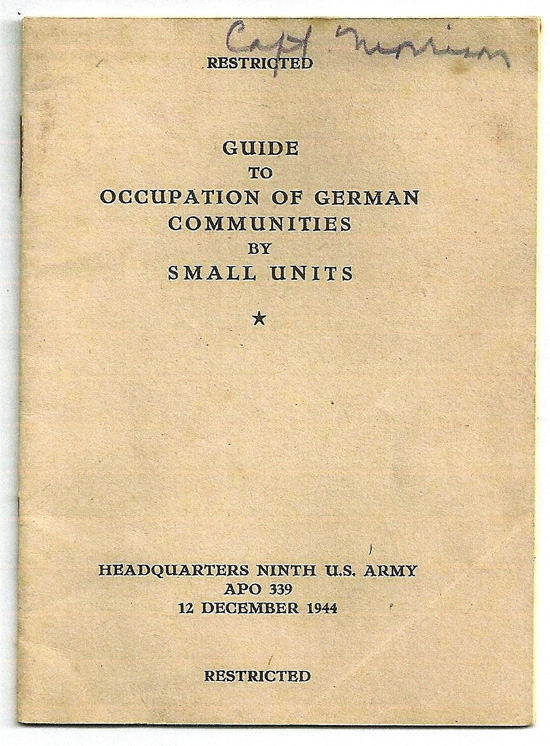

Copy illustrating “Guide to Occupation of German Communities by Small Units”, issued by Headquarters Ninth United States Army, APO # 339, dated 12 December 1944, and signed by Brig. General J. E. Moore, Chief of Staff. This 10-page booklet was prepared in order to provide Battalion, Company, Platoon, and similar unit Commanders with a handy reference covering those matters most likely to be encountered during the attack and occupation of Germany. It covered such subjects as Occupation Instructions and Non-Fraternization Instructions.

End of Assignment:

Captain P. J. Morrison, MC, O-1685862, was relieved from active duty as per RR1-5 (Demobilization), Paragraph 30, Special Orders # 277, 1378th Army Air Force Base Unit, Fort Totten, Bayside, Long Island, New York (Antiaircraft Artillery Camp –ed), dated 4 October 1945. He left the European Theater on 3 October 1945 by air with destination the Zone of Interior, where he arrived 4 October 1945. After spending some rest with his Family, he was transferred to Fort Devens Separation Center, Ayer, Massachusetts (Military Reservation –ed), where he was honorably discharged on 23 December 1945.

The 24th Evacuation Hospital was stationed in Rotenburg, Germany, from 27 August 1945 on, where it was officially inactivated 4 February 1946.

On 28 November 1945, Colonel Wallace H. Graham, White House Surgeon, recommended the Officer for the Bronze Star Medal. The reason indicated for the award was as follows: “During the period of 12 June 1944 to 1 November 1944 as General Surgery Team Chief, Captain Philip J. Morrison, worked untiringly during the entire combat operations In a steady, driving and cooperative manner he achieved a high degree of efficiency in his group, thus contributing in a great measure toward the superior functioning of the Hospital under shellfire and trying conditions. The extremely low mortality record of seven-tenth of one percent for ten thousand seven hundred and eighty-five (10,785) surgical operations out of twenty-three thousand (23,000) casualties admitted was outstanding. His personal attentions were of great benefit to the patients and the expeditious treatment and care during and following surgical procedures. He rendered service exceptionally meritorious in character and above that of regular assigned duty.”

After retiring as a Major in the Reserves, US Army Medical Corps (1948), Dr. Morrison served as Assistant Chief of Surgery at the Richmond, Virginia, VA Hospital from 1945 to 1952 (ex-McGuire General Hospital, Richmond, Virginia, named after Dr. Hunter H. McGuire, Medical Director, Second Army Corps, Confederate Army (1835-1900), designated US Army General Hospital by War Department General Order # 48, dated 24 November 1943, and arrival of its first patient on 29 July 1944, with a total bed capacity of 1,765. Its specialties included neuro-surgery and amputations, the Army Hospital was transferred to the Veterans Administration 31 March 1946 –ed) and later as Chief of Surgery at the Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, VA Hospital, in 1952-1953.

Dr. Morrison returned to civilian life accepting an appointment as Chief of Surgery, 1964-1969, and Chairman of the Medical Board at Woonsocket, Rhode Island Hospital 1969-1971. He published several treaties and studies. He finally retired in 1979. Dr. P. J. Morrison passed away 26 September 1987 in East Orleans, Massachusetts after a long illness, at the age of 77.

Decorations

American Campaign Medal

European, African, Middle Eastern Service Medal

World War Two Victory Medal

Army of Occupation Medal (Germany)

Bronze Star Medal

Campaign Credits

Normandy (ref. GO # 33, WD 1945)

Northern France (ref. GO # 33, WD 1945)

Rhineland (ref. GO # 40, WD 1945)

Central Europe (ref. GO # 40, WD 1945)

Portrait of Captain Philip J. Morrison, taken around the end of his stay in the European Theater of Operations. He served “honorably” in active Federal Service in the Army of the United States from 4 July 1942 to 23 December 1945.

Our special thanks go to Taffy Morrison McGann and Dave S. Morrison, daughter and son of Captain Philip J. Morrison (O-1685862) Surgeon with the 24th Evacuation Hospital, for spontaneously sharing their Father’s WW2 recollections and photos relating to his military service with subject medical unit in the European Theater of Operations. Without their precious help, the MRC Staff would not have been able to edit this captivating Testimony.