Evolution in Packing of Medical Items

Introduction:

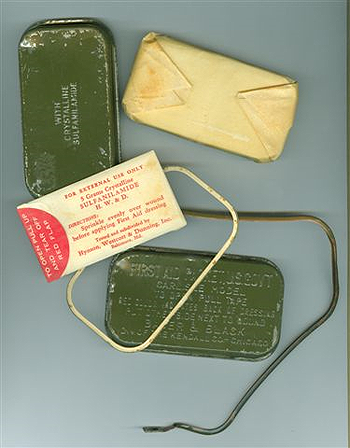

Apart from the individual First-Aid Packet, U.S. Army Carlisle Model (the only dressing to be packed in a small metal container) the majority of all bandages, dressings, compresses, tourniquets, ampules, burn-injury sets, eye-dressing sets, adhesive plasters, gauze rollers, ointment tubes, iodine swabs, sulfanilamide powders, tablets, pills, in general use with Medical Department personnel, were usually packed individually in tuck-end cartons bearing the proper nomenclature and markings of the supplier, distributor, or manufacturer.

Opened view of First Aid Packet, US Gov’t, Carlisle Model, illustrating its different elements.

Evolution:

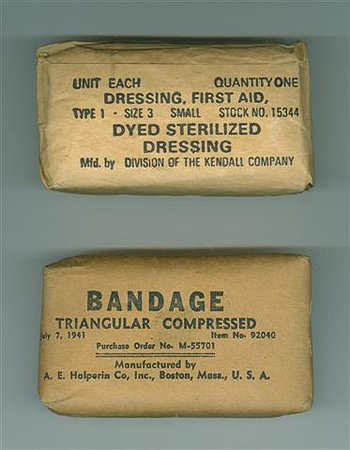

Figure illustrating different types of brown Kraft paper wrappers used for packing Dressings and Bandages. Top: stamped markings; bottom: printed markings.

Early in WW2 and following previous standards (as applied in the Great War and during the interbellum years), many medical items were merely wrapped in white or brown kraft paper and marked in black (stamped or printed). At the beginning, commercial products were still in vast supply (for commercial reasons, packaging, appearance, outlook, and overall presentation were always highly stressed), but gradually concessions and amendments were introduced with respect to color, weight, protection, presentation, in order to reduce cost, supply, and limit visibility (items mainly used in the field). U.S. Government requirements implied certain rules with respect to the use and display of Medical Department stock numbers, contract numbers, manufacture dates, specifications, patents, etc. and the fact that the ‘product’ was destined for official U.S. Government use (i.e. the Army of the United States).

Figure illustrating different samples of waxed First-Aid Dressings and Gauze Compresses.

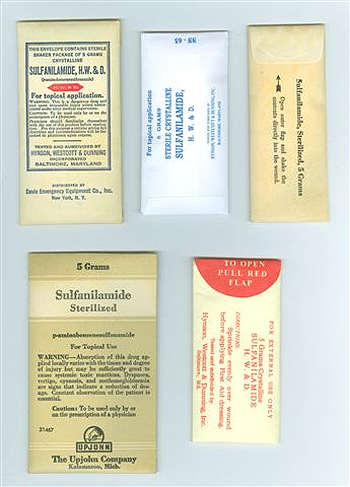

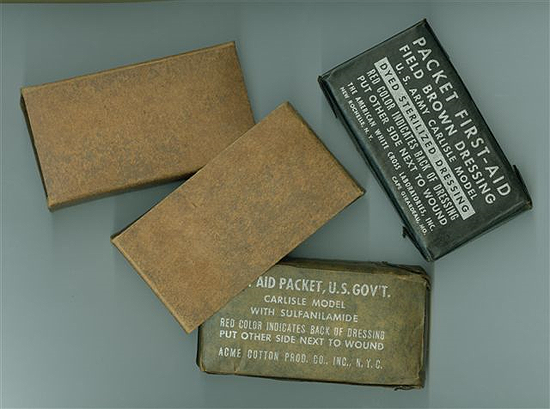

Certain fragile products (glass vials and ampules, ointment tubes) were packed in cardboard protected by individual carton liners or wrapped in cloth for extra protection. Other items (dressings and bandages), were usually packed in cartons, and either covered in wax, sealed in cellophane, wrapped in coated or waxed glassine, for enhanced protection in the field or for storage, or simply left as such. Sulfa powders came wrapped in paper shaker envelopes (white and colored), or their contents (tablets) protected with laminated paper, metal (aluminum or lead) foil and then heat-sealed, etc. Following metal shortages, the Small, First-Aid Dressing, U.S. Army Carlisle Model (previously packed in a metal container), was packed in a rectangular tuck-end carton, printed with the required markings, and dipped in wax (water-repellent treatment). In 1943, research for the conservation of foods and rations brought about some important changes in protection and packing methods, which was to favorably influence the packing of dressings and bandages. The items were now wrapped in laminated paper, reinforced with aluminum or lead foil, and covered internally with either pliofilm, cellophane, or polyvinyl butyral. The item was then covered with an appropriate waxed cardboard shell for enhanced protection. Some products required more care than others. One such item was Plaster of Paris, which was wrapped in asphalt-based laminated paper for protection again moisture and dampness. Another one was the Petrolatum dressing developed later in the war (1944-45). This dressing, consisting of a gauze bandage impregnated with petrolatum, permitted the application of a sterile product to a burned surface and thus was a significant medical advance in a war which, more than any previous one, produced many serious and painful burns. Two technical difficulties confronted the sole supplier of this item: the development of a technique to produce a sterile dressing, and the manufacture of a grease-proof package which would withstand high sterilization temperatures. The petrolatum and the gauze bandage were sterilized separately and were then brought together under sterile conditions. The envelope for the individual dressing was a lamination of vinylite and aluminum foil, which was heat-sealed after the bandage was impregnated with the sterile petrolatum. Three of these dressings were then packed in a Reynolds Metals envelope, reading for distribution.

Figure illustrating some First-Aid Dressings and Sterilized Gauze Compresses packed in cartons and wrapped in cellophane for extra protection.

Procurement of some items of surgical dressings was attended with considerable and peculiar difficulties. The production of camouflage dressings, for example, created problems which could not be solved routinely. By the end of 1942, it had been well established that white surgical dressings (highly visible) were attracting too much attention from the enemy. The decision was therefore made to dye in “field brown” (other designation: “camouflaged”) all white field dressings and in July 1943, instructions were issued to that effect. This decision presented a number of problems to the Supply Service and its contractors, including the toxicity of the dyes, effect on the absorbency of the gauze, the industry’s ability to convert to dyed dressings, and the productive capacity of dyers and finishers. Outstanding contracts for several items of white dressings were modified, and work on the field brown dressings was started in September 1943. After several experiments, a non-toxic dye which had only slight effect on the absorbency of the gauze was produced. By November 1943, over 13,000,000 individual dyed dressings had been delivered to the Medical Depots. Throughout the remainder of the war, adhesive compresses, 2-inch and 4-inch gauze compresses, compressed bandages, small first-aid dressings, large first-aid dressings, first-aid packets, and triangular bandages were supplied either in field brown or in olive drab.

Figure illustrating different types of Sulfanilamide paper shaker envelopes.

Conclusions:

Figure illustrating two different types of First-Aid Packets packed in laminated paper with aluminum foil wrappers and protecting cartons. Note the top one is a ‘field brown’ dressing, while the bottom packet contains ‘sulfanilamide’.

Apparently well-known important manufacturers kept their commercial products without any changes throughout World War 2, and signed contracts with the Government, without significant alterations or amendments to the looks, the markings, and the packaging. Others made concessions and in order to obtain large-scale contracts, changed colors and markings, to keep prices down. This explains the wide variety of medical items in circulation during the interbellum years and the early start of World War 2. Changes did continue to occur during the war, based on advanced manufacturing methods and packing techniques, which no doubt influenced overall production of medical products.

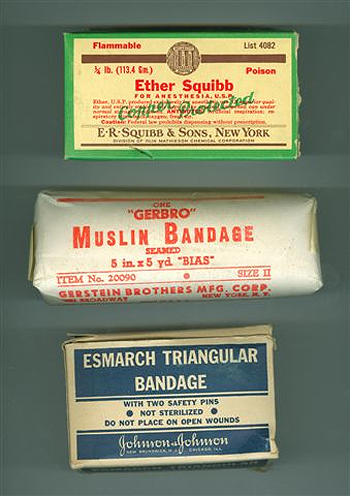

Figure illustrating three fully-colored commercial and US Government contracted medical items from different suppliers. It should be noted that while E. R. Squibb & Sons and Gerstein Bros. continued to produce items in multi-colored cartons, Johnson & Johnson eventually elected to pack their products in simple natural-colored cartons with black markings.

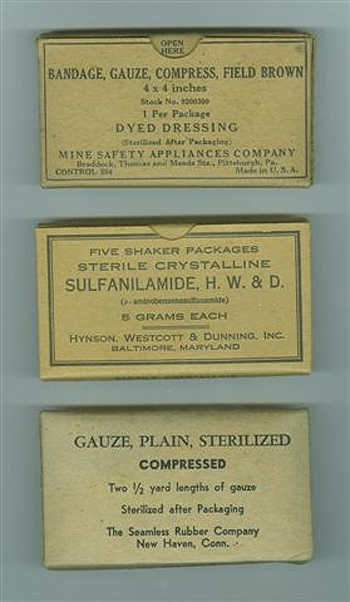

Figure illustrating three different suppliers packing their medical products in natural-colored, dyed light-to-medium brown cartons. This method and packaging applied in the majority of cases, in fact became the norm in World War 2.

The authors are still looking for any official US Government documents and/or data governing specifications, production requirements, packing procedures, markings, etc. pertaining to major Medical Department items such as dressings and bandages used during World War 2. Sources will always be acknowledged and indicated. Thank you.