5th Evacuation Hospital Unit History

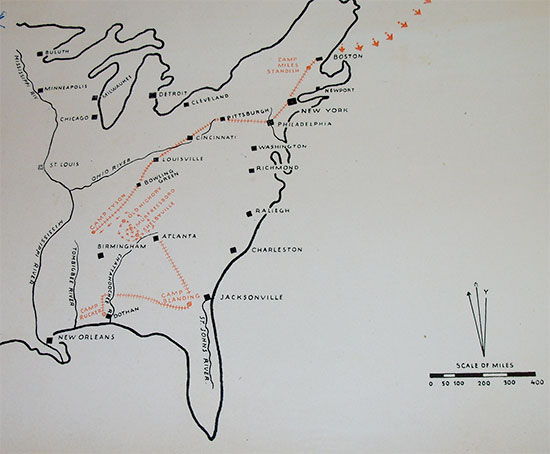

Map of the eastcoast of the United States illustrating the various stages of movement effected by the 5th Evacuation Hospital in the Zone of Interior from activation to departure for overseas (15 June 1942 > 6 December 1943).

Introduction & Activation:

The 5th Surgical Hospital was re-constituted 9 November 1936 in the Regular Army and concurrently consolidated with the 5th Evacuation Hospital (already constituted in the Organized Reserves as Evacuation Hospital No. 5, and re-designated 5th Evacuation Hospital 23 March 1925 –ed). The 5th Evacuation Hospital was withdrawn from the Reserves 1 October 1933 and subsequently allotted to the Regular Army. It was officially activated 15 June 1942 at Camp Rucker, Ozark, Alabama (Division Camp; acreage 58,999; troop capacity 3,200 Officers and 39,461 Enlisted Men –ed), reference: War Department, General Order No. 56, Section III, Headquarters, Second United States Army, Memphis, Tennessee, dated 9 June 1942 (the 5th Surgical Hospital was originally organized 20 November 1917 as the Evacuation Hospital No. 5 and was demobilized 14 March 1919 –ed).

On 12 March 1943, the unit was re-organized and re-designated as the 5th Evacuation Hospital, Semimobile.

Organization:

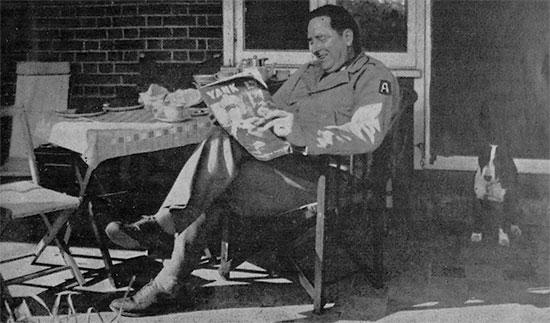

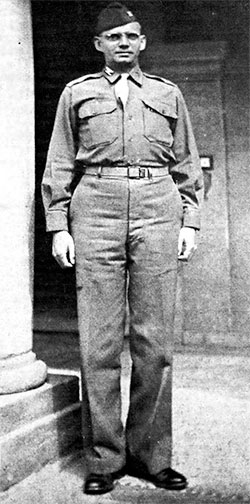

Photo illustrating Lt. Colonel Charles L. Baird, Commanding Officer 5th Evacuation Hospital (29 November 1942 > 28 February 1945).

Lt. Colonel V. Snell assumed command of the unit on 15 June 1942. He was joined by Chaplain Willis A. Brown. A cadre comprising 1 Officer and 23 Enlisted Men arrived the same day from Fort Dix, Wrightstown, New Jersey (Training and Pre-Staging Center; acreage 28,344; troop capacity 1,825 and 51,598 Enlisted Men –ed) to help form the new Hospital. More Officers were assigned and joined the organization in July and August 1942.

Commanding Officers – 5th Evacuation Hospital

Lt. Colonel V. Snell > 15 June 1942

Captain Louis Baer > 14 November 1942

Lt. Colonel Charles L. Baird > 29 November 1942

Colonel Erling S. Fugelso > 6 March 1945

Change of Station & Training:

On 30 September 1942 the outfit folded its tents at Camp Rucker and moved to Camp Blanding, Starke, Florida (Infantry Replacement Training Center; acreage 152,672; troop capacity 2,157 Officers and 58,570 Enlisted Men –ed) where it arrived 1 October 1942.

On 27 October 1942, 63 additional EM were assigned from the Reception Center, Camp Blanding, Starke, Florida, and another 75 Enlisted Men were assigned from the Reception Center, Camp Upton, Long Island, New York on 28 October 1942. Additional personnel joined in order to reach the authorized T/O strength.

The first 11 Enlisted personnel were sent to School at William Thomas Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colorado, on 29 October 1942. Other men went to several Schools specializing to become either Dental, Medical, Surgical, or Sanitary Technicians.

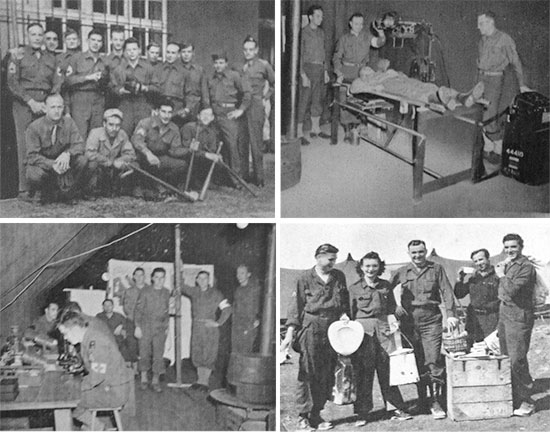

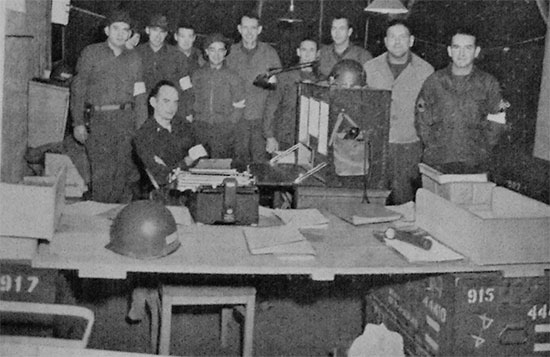

Photo illustrating group of personnel of the 5th Evacuation Hospital, taken at Camp Blanding, Florida, where the unit trained from 1 October 1942 to 1 March 1943.

30 October 1942 14 Enlisted Men were assigned from the Reception Center, Fort Custer, Battle Creek, Michigan; followed by another batch of 75 EM coming from Camp Upton, Long Island, New York, on 2 November. While in Blanding, more casuals arrived from the 9th Evacuation and 16th Evacuation Hospitals as well as from other places in the Zone of Interior. In the end the unit reached its major strength of Enlisted personnel, well over the authorized T/O.

A change of command took place 14 November 1942, whereby Lt. Colonel V. Snell left the 5th Evacuation for the 9th Evacuation Hospital. Captain Louis Baer was temporarily appointed Commanding Officer. The Officer did not remain in charge for long as Lt. Colonel Charles L. Baird took over command of the 5th Evacuation Hospital on 29 November 1942.

Following tests, it was decided to send 9 EM to John Shaw Billings General Hospital, Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, for training. One NCO, Sergeant B. Goldheimer went to Officer Candidate School. A number of men (overstrength) were either transferred or made fit for discharge (including quite a number of 4F cases). Notwithstanding the absence of a number of personnel, cleaning details were always at work to keep the barracks impeccable, and training continued with obstacle courses, morning runs, classes, and night problems. The final phase of basic and technical training was foreseen for the end of January 1943.

Photo illustrating Lt. General Ben Lear, Commanding General Central Defense Command, while inspecting Second United States Army troops during a visit to Camp Crowder, Neosho, Missouri (the General also visited the 5th Evacuation Hospital at Camp Blanding, Starke, Florida, on 18 February 1943).

A Christmas Party was held in Recreation Hall 507 with a grand show given by the Enlisted personnel. More Officers joined the unit 30 December 1942. During the above period the 5th Evac was training alongside the 24th Evacuation Hospital and both units decided to organize a dance at the local Service Club (the 24th Evac was stationed in Camp Blanding from 1 October 1942 until 18 September 1943 –ed).

More serious work began 30 January 1943, when a week-long bivouac was organized. As full T/O strength was not yet achieved, another group of 5 Officers (Lieutenants Jacques Cousin, Grover C. Jackson, Edward B. McColly, Mocko, and Joseph V. Ramp) were assigned and joined the unit on 6 February 1943 (this process continued well into the months of March through April, even including May and June 1943 –ed). The bivouac ended with latrine rumors stating that the unit was headed for maneuvers in the hills of Tennessee.

Driver Michael V. Cecconi with a new 3/4-Ton, 4 x 4, Ambulance vehicle for transporting sick and wounded personnel. Photo taken during the 1943 Tennessee Maneuvers, Zone of Interior.

On 18 February 1943, an official unit review of Second US Army posts and camps took place with Central Defense Command Commanding General, Lt. General Ben Lear (1879-1966) inspecting the unit. This was followed by another formal review and parade by the Camp Blanding Commanding General, Brigadier General Louis A. Kunzig (1882-1956, in command of the IRTC from 1941 to 1944 –ed).

On 1 March 1943 the unit moved to Gold Head Branch State Park (developed on a 2000-acre site by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s –ed) for another week’s bivouac. During subject period, training focused on pitching heavy tentage and improving skills for use in the field. Drill, marches, and miscellaneous field exercises continued. Another important date in the unit’s history was the publication of the first issue of its newsletter entitled “The Needle”, which took place 12 March 1943. During the unit’s stay at Camp Blanding additional Officers joined the command and a reshuffle of staff functions was carried out with the following results:

Lt. Colonel Charles L. Baird > Commanding Officer

Captain Edward R. Marshall > Executive Officer

Captain Ruth Baldwin > Chief Nurse

Captain Clarence E. Allen > Chief Dental Section

Captain David F. Johnson > Neuro-Psychiatry Officer

Captain Frank H. Threlkel > Chief Roentgenological Section

Captain Louis R. Way > Chief Surgical Service

1st Lieutenant Nathan Brody > Chief Pharmacy & Laboratory Section

1st Lieutenant James F. Bucker > Class “A” Paying Officer

1st Lieutenant Jacques Cousin > Adjutant

1st Lieutenant Grover C. Jackson >Transportation Officer

1st Lieutenant Clifford F. Marian > Special Service Officer & Personnel Adjutant

1st Lieutenant Edward B. McColly, II > Registrar

1st Lieutenant S. Mihalich > Detachment Commander

1st Lieutenant Joseph V. Ramp > Asst. Supply Officer

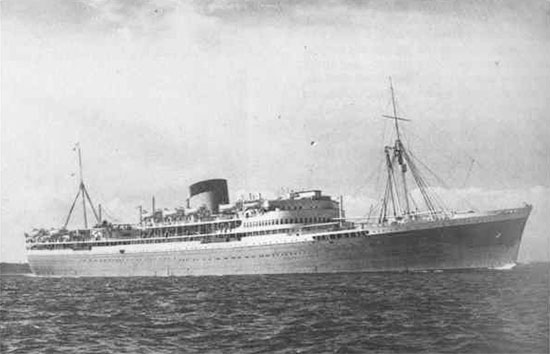

Photo of MV “Stirling Castle” (launched in 1936, eventually converted to a troopship, used for transportation of US troops to the United Kingdom) before its conversion for military use.

Between 9 and 12 April 1943, the unit went on a bivouac at Silver Springs, where it remained longer than planned, only returning to garrison duty on 17 April. Training was continuous and to keep the men in good physical condition, softball teams played against other units, and 15-mile marches were organized. On 29 April 1943 a full-scale inspection took place by a team from Second United States Army. Another group of 35 Enlisted Men joined the 5th from Camp Barkeley, Abilene, Texas (Medical Replacement Training Center & Armored Division Camp; acreage 69,879; troop capacity 3,192 Officers and 54,493 Enlisted Men –ed) on 9 May 1943.

20 May 1943 was an important day when Lieutenant Colonel Charles L. Baird was promoted to full Colonel.

More personnel continued to pour in, with 17 additional EM received from Camp Joseph T. Robinson (Infantry Replacement Training Center; acreage 42,124; troop capacity 2,596 Officers and 44,077 Enlisted Men –ed) on 10 June 1943.

Tennessee Maneuvers:

On 13 June 1943, the 5th Evacuation Hospital left Camp Blanding, Florida, at 0515 in the morning, for a ‘station’ somewhere in Tennessee (this was Camp Forrest –ed), where it was to operate a hospital to support the Red or Blue Army. Everything happened under the utmost secrecy with censorship strict during travel. The bivouac site was reached at 0830 the same day. It was situated approximately 3½ miles northwest of Shelbyville, Bedford County, Tennessee. Meanwhile more MC and MAC Officers arrived.

All through basic training, and after this period, the organization had its full complement of Enlisted Men, but it was only through May and June that the Medical and Surgical Officers arrived in sufficient numbers to give the 5th their approximate official T/O strength. As maneuvers were about to begin, the first quota of ANC Officers arrived – 20 in all (commanded by one 1st Lieutenant –ed). Life during maneuvers was new to all, more particularly for the Nurses; washing out of a helmet, wearing those horrid fatigues, and waiting impatiently for the week-end that brought Nashville, a hotel, or a bath, and some recreation (the latter applied to Officers only –ed).

On 25 June, the outfit moved into a National Guard garage building in Shelbyville, already established as a temporary hospital by the 45th Evacuation Hospital and took over 60 of their patients. More immediately began to pour in and by midnight there were 158. Much was learned during maneuvers which would prove very helpful during the unit’s stay overseas. The first phase of the maneuvers ended on 7 July 1943 and a ‘watermelon’ party was held to celebrate the occasion. Following in the tracks of the ‘victorious’ Army, the hospital moved on to Murfreesboro (Rutherford County –ed), Old Hickory (Davidson/Wilson County –ed), and upon reaching the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) barracks, peace between the Red and Blue Army had been declared (numerous moves took place during July and August, with the personnel learning the necessary tricks how to pitch and strike tents in the shortest possible time –ed). The 5th only played a small part in the next phase of maneuvers, and between 1 and 2 October 1943 moved to Camp Tyson, Paris, Tennessee (Barrage Balloon Training Center; acreage 7,014; troop capacity 772 and 12,543 Enlisted Men –ed) for a permanent change of station.

5th Evacuation Hospital personnel sightseeing in Oxford, England.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

Maneuvers with its ever shifting scenes of mud and sand, its blackout conditions, its night marches, its IG (Inspector General) inspections one week, and command inspections every week, and only brief stays in Nashville for recovery were over after moving to Camp Tyson. The main group joined the advance party which had made the usual preparation for the unit’s arrival at the new station. Another 20 ANC Officers were assigned to the organization on 9 October 1943.

It was felt that it would only be a stop over, rife with rumors about a forthcoming trip overseas!

After sweating another month in training, lectures, drill, road marches, hikes, and improving medical and other skills, the 5th Evac finally moved on 20 November 1943, secretly by train, to another permanent change of station. The weather was good, morale excellent, and rumors abounded, as ‘destination’ remained, once more, unknown.

The men stepped off the train on a cold, misty day, which set the mood for the stay. After the ‘lavish’ quarters at Camp Tyson, the honeymoon period was over.

While getting organized, processed and checked by frequent showdown inspections, the personnel practiced answering roll calls to loading lists of personnel. As everyone expected to leave any day now, many grasped the opportunity to take a last fling at the not too distant New York, nearby Boston, and other places in between. Thanksgiving was celebrated in group.

Starting 4 December 1943 the entire unit was restricted to the area as of 1500 hours. All telephone communications were cut off, no letters could be sent out, and then the loudspeaker blared out “2645-V” (the unit’s code number –ed), and alert orders were confirmed. After feasting on a sumptuous meal of chicken, stuffing, peas, coffee, ice cream and pie, the unit entrained on 5 December for the Boston Port of Embarkation. Steel helmets had been numbered in sequence to facilitate entraining and later boarding, loaded with shelter halves, duffel bags, musette bags, gas mask, pistol belt, medical pouches harnessed on, the 5th managed to arrive intact at Boston POE at 1700 hours.

Photo illustrating a British Infantry Landing Ship, of the “Empire Mace” Class, used for transportation of the 5th Evacuation Hospital staff and personnel across the English Channel to France 13 June 1944.

More controls, checks, and instructions followed, with port personnel checking the names against the unit roster, and the ARC serving the traditional donuts and hot coffee. Burdened with baggage the staff and personnel climbed the gangplank (boarding ended at 1900 hours) reaching the upper deck where an ever ready and alerted British crew directed everyone to their assigned quarters. Soldiers filled the ship and they were everywhere, on the floors, in passageways, so, some reshuffling was done by the brass to try and get each subunit assigned to a proper section of the ship. After loading was accomplished, the “Stirling Castle” (ex-Union Castle Liner sailing between England and the Cape of Good Hope –ed), left at 0600, on the morning of 6 December 1943 part of UT.5 convoy bound for the United Kingdom.

During the 11 days at sea, the men accustomed themselves to the ship’s routine. Instructions were given on a daily basis, accompanied by ‘abandon ship’ drills, blackout exercises, no smoking on outer deck after 2100 hrs, standard regulations, and many more. The Enlisted Men were strung up on canvas bunks, one to four tiers high, with all remaining space appropriated for individual gear. Undressing, dropping shoes, or snoring, were affecting the other troops, since everyone was staying close by in this restricted space. Officers were distributed over the available staterooms.

It was thrilling to observe the many other ships in the convoy and comforting to watch the escorting naval vessels on the horizon. Thanks to the open air and salty breeze, most personnel developed a ravenous appetite. Unfortunately, only two meals were served per day, and the long EM chow lines could not actually solve the problem. Those men at the end of a chow line, quite often reached the head just in time for the next meal. It was also a question of keeping one’s balance because of the slippery greasy mess floor where food was served, furthermore, eating while standing was not very comfortable either. Not being accustomed to a sea voyage, almost everyone had attained their sea legs only after the first 48 hours of sailing. Apart from the daily work details, some activities such as crap and cards seemed popular to help pass the time away.

Finally following an uneventful sea voyage, the ship came down the North Channel into the Irish Sea, slowly approaching the port of Liverpool, England.

Rhino Ferry on its way to shore, loaded with vehicles belonging to the 5th Evacuation Hospital. While being ferried to Omaha Beach, Private Rocco Mannino, acting on an Officer’s order drove one of the 2 1/2-Ton Trucks into the sea (the water was too deep). This incident took place 13 June 1944.

United Kingdom:

After reaching Liverpool 15 December, the “Stirling Castle” debarked her passengers at 2100 hours, 17 December 1943. The British Red Cross welcomed the unit with coffee and sandwiches, and in total blackout the men marched to the waiting British troop train. Traveling all night, all slept fitfully after a long and tiring journey. It was the 5th’s first acquaintance with the Army’s K-rations. The group detrained at Bracknell, Berkshire, on Saturday, at 1000 hours, 18 December 1943, from whence they moved by shuttle convoy, in rain and fog, to Wokingham, Berkshire. After a hot lunch at the bowling alley, members of the unit were assigned private billets, and from thereon, friendly contacts developed between the personnel and the people of Wokingham. A temporary Headquarters was established in ‘Northbrook House’, but was subsequently moved to ‘Clair Court’ upon departure of the Engineer unit leaving the 5th momentarily as the only US troops in town. Christmas would be celebrated on ‘foreign’ soil, with lots of Officers and Enlisted Men being invited to English homes for Xmas dinner.

After the usual amount of billet shifts, a certain routine existence was established and personnel began to gradually learn something of English life. Britain was ‘blitzed’, rationing was enforced, and more US troops came in. Drinking habits and the type of beverages offered differed a lot from the US, and the monetary system was not only difficult to grasp, but the exchange system confusing.

Site of Advanced Landing Ground A-9 (built by the IX Engineering Command) being established approximately 2 miles north of Le Molay. The 5th Evacuation Hospital set up camp near this Airfield 15 June 1944.

In time a training schedule was made part of daily life and classes were held everywhere in town. The drill hall of the Wokingham Guards was used on Saturdays. Orientation courses were given with classrooms sometimes set up in churches, the Bowling Green, and the Rectory. Road marches were frequent, with troops discovering the byways of surrounding Berkshire. Outside instruction came in the form of a local combination of an Air Raid Warden and a Bomb Disposal Officer (both British personnel –ed). Mock hospital setups were made around town and a timed-speed tent pitching test performed. Field sanitation was always enforced, whatever the terrain.

When passes became available, almost everyone saw London for the first time. There were also nightly excursions to nearby Reading, the only difficulty being the early departure necessitated by the stoppage of train service. Some members had the somewhat unenviable experience of an extra march from Reading to Wokingham in the absolute dark of a full blackout. Quite a warm friendship was established with townspeople as demonstrated by several dance parties given by the town and by the 5th Evac in return. Individual friendships developed resulting in dinners, receptions, and certain more permanent relations.

On 11 April 1944 the 5th Evacuation Hospital was officially “alerted” for a possible move overseas. Yet it would be 27 May before final orders came through, and on that day any excess clothing, including olive drab service caps, was to be turned in. Due to the impending crossing of the English Channel it was desired that all members of the command became proficient in the art of swimming; a thorough survey showed that 81 members of the organization did not know how to swim (courses were organized and men were invited to report to the motor pool at 1500 hours for a two-hour crash course of instruction on dry land –ed).

Eventually final preparations for a possible move to the continent were started, it was time for combat. Boxes and crates were built, painted, waterproofed, and stenciled or marked with number “44410” and three horizontal colored bars, buff-brown-buff. This was followed in natural sequence by the packing and loading of the organization’s organic equipment. A convoy was formed before Headquarters stretching for more than three blocks, bumper to trailer, and dry-runs were organized. The last formal inspection before moving to the Marshalling Area took place 29 May 1944.

In accordance with the customary regulations prior to any movement 5th Evac Headquarters was buried under a load of paperwork. The shipping list involved an addition of long columns of figures (an adding machine was therefore borrowed from a local business establishment; unfortunately, the idea fell through, as the machine insisted on working on the basis of British currency, and the addition was never completed). A forecast of the impending Invasion came one morning in the form of a glider towing air armada flying overhead during a rehearsal for the Invasion. Full realization only came after 6 June 1944, when the unit first heard of the Invasion of France, and completed final loading.

Top left: Members of the 5th Evacuation Hospital Softball Team.Top right: 5th Evacuation Hospital personnel at work in the Roentgenological Section, while stationed at La Fortière, France, in August 1944.

Bottom left: Partial view of the 5th Evacuation Hospital’s installations under tentage, while stationed at Herbesthal, Belgium, in September 1944. The stay was particularly remembered as the period of ‘mud and galoshes’.

Bottom right: Members of the 5th Evacuation Hospital showing some of their daily ‘paraphernalia’…

Departure of the first echelon took place the morning of 7 June (at 1015 hours) when most of the staff and personnel with packs and baggage staggered to the local railroad station and formed to await transportation. With arrival of the troop train a hasty boarding was performed. Lunches were consumed about three miles out of Wokingham as hope was expressed for a short ride. A southwesterly route was taken, including in its course, Winchester. The first echelon under the command of 1st Lieutenant Frank H. Threlkel, arrived at the Marshalling Area, Camp C-17 near Southampton, where trucks took them into the camp. The time was about 2330. The second echelon comprising 8 Officers, 63 Enlisted Men, and all supplies and equipment, under the command of Colonel Charles L. Baird was billeted in Camp C-14, Marshalling Area, Southampton, England. No provision had been made to house the ANC Officers, so the Nurses were temporarily housed at the 46th Field Hospital.

While being restricted in its Marshalling Area, the unit was surrounded by thousands of troops, all quartered in pyramidal tents, awaiting the signal, to start their way across the Channel and land on the coast of France. Invasion currency was distributed on 8 June, and impregnated clothing tried for size the next day. The necessary rations, including D and K were issued. Men and heavy equipment were constantly arriving and departing with great efficiency and under secrecy.

France:

On D+3 (9 June 1944) the day ended when Colonel Charles L. Baird’s group (second echelon) departed from the Marshalling Area and arrived at the Port of Southampton around 2000 hours. Upon arrival immediate preparation was made to load vehicles, equipment, and supplies aboard the Liberty Ship USAT “David Caldwell” (launched in 1943, sank in 1946 –ed). Personnel were issued life preservers and eventually shown to their quarters.

Meanwhile, 1st Lieutenant Frank H. Threlkel’s group remained in the Marshalling Area until 12 June 1944, when they were instructed to proceed to Port. Prior to departure, every man was issued chewing gum, matches, insecticide & louse powder, water purification tablets, seasickness tablets, and two vomit bags. After a short delay due to congestion at the port, the men embarked on the British Infantry Landing Ship “Empire Mace” at 1750 hours. At precisely 2100, HMT “Empire Mace”, LSI (L) (launched in 1943 –ed) slipped into the treacherous waters of the Channel, following other numerous ships bound for the shores of France. The following morning at 0200 hours, aboard the “Empire Mace”, an air alert was sounded as it seemed that enemy fighters had been sighted. All the personnel jumped from their bunks, and already dressed and lifebelted, waited for the inevitable. Although no action was taken by the ship, ack ack could be heard from other vessels in the distance. Alert terminated in ten minutes but everyone preferred to remain awake in case of another attack. After five more hours of sheer night, light streaks appeared in the sky. And about 0700 a bluff appeared in the distance – the French coast.

Within a few minutes HMT “Empire Mace” dropped anchor about one and a half miles off Omaha Beach. At 1430, all personnel debarked in barges and ferries, and after assembly, spent their first night in Normandy in an apple orchard.

Photo illustrating personnel of the 5th Evacuation Hospital, while stationed at Eupen, Belgium, October – December 1944.

In the meantime the group under command of Colonel Charles L. Baird, with the motor convoy, had begun unloading at 0100 with the first 10 vehicles transported on rhino ferries. During the transfer from ferry to shore some difficulty was experienced and 3 trucks drove into the sea. At the command “Take off” the drivers had insisted that the water was too deep, but the Officer would not relent and in they all plunged up to their heads! Some of the drivers could swim but one couldn’t. Eventually the 3 men reached shore unharmed, but without their trucks. The rhino ferry backed off safely and unloaded the remaining trucks further on the beach. Due to some interference by the Luftwaffe, it was impossible to retrieve the waterlogged trucks until the next morning.

Meanwhile those men on board the USAT “David Caldwell” spent the night watching the huge barrage of antiaircraft and machinegun fire thrown up each time an enemy plane came over.

The remaining trucks containing the hospital’s equipment were unloaded uneventfully and all headed for the Assembly Area at St. Laurent-sur-Mer. Here the trucks were parked under the trees so that de-waterproofing could begin and a bivouac established. Colonel Charles L. Baird and 1st Lieutenant Jacques Cousin set out to locate the remainder of the trucks and personnel from the “Empire Mace”.

In the full light of day, the personnel bivouacking under the trees could look down the bluff at Omaha Beach spread out below and contemplate what looked like an immense junkyard. From the water’s edge at low tide to the high mark were landing craft, some impaled on anti-landing obstacles, others half sunk, many wrecked by mines or shattered by enemy shellfire, and others just stranded by the ebbing tide. Discarded equipment littered the beach, with items such as lifebelts, empty cartridge clips, canteens, web gear, rations, and countless mementos of the battle that preceded the 5th’s arrival. Demolition charges still popped off at intervals along the beach to remove obstacles and widen roads loaded with vehicles of all descriptions and endless columns of moving men (reinforcements and supplies coming in –ed). Nurses from the 5th Evacuation, the 24th Evacuation and the 41st Evacuation Hospitals joined the 13th Field Hospital at its hospital site. When serving under FUSA control, the Evacuation Hospitals operated under the following code names: 5th Evacuation Hospital (“Medicine 5”), 24th Evacuation Hospital (“Medicine 24”), 41st Evacuation Hospital (“Medicine 41”), 13th Field Hospital (“Mermaid”). While waiting to rejoin their parent unit, the ANC Officers were temporarily quartered in tents set up by Enlisted personnel from the 13th Field. During the first night in France, enemy planes droned overhead. With all the noise, it was difficult to catch some sleep. The personnel only slept one night in the area and next morning (14 June 1944) left for Le Molay, France (south of Trévières –ed).

Members of the 5th Evacuation Hospital Dental Section in action, while stationed in Belgium.

Stations in France – 5th Evacuation Hospital

Le Molay – 15 June 1944 > 27 June 1944

La Mine– 12 July 1944 > 3 August 1944

La Fortière – 7 August 1944 > 13 August 1944

The 5th Evac arrived in Le Molay on 14 June 1944, and was already able to open for receiving patients by 1150 hours 15 June 1944, receiving its first patient – Pfc Charles Miller, ASN 18029597. The site was situated approximately 8 miles inland opposite A-9, an Advanced Landing Ground (ALG) constructed by the IX Engineering Command just across the road. There was an Ordnance unit to the front, elements of the 2d Armored Division on the side, and the 41st Evacuation Hospital behind the unit. Although fine neighbors, they attracted too much attention from the Luftwaffe. Regularly at 2300 and 0600 hours, enemy planes flew over the hospital. A first strafing took place 20 June, with the first casualties; Private First Class Edgar H. McCullough (foot wound) and Sergeant Louis Giuliano (minor lacerations). Most men lay on the ground watching the aircraft, while others rapidly ducked into foxholes. The 5th Evac operated at Le Molay from 15 to 27 June 1944 acquiring its first battle experience. However, the tremendous flow of incoming casualties at one time was a critical problem. The unit was put on a 12-hours shift basis with more help on the way. Borrowed Medical Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men, and changes in the organization increased the hospital’s efficiency. Gradually the organization emerged from the dark days and difficulties to attain the confidence of battle-scarred veterans. The 5th Evacuation Hospital received neuropsychiatric patients on 16 June and closed the N-P service on 28 June after having received a total of 91 patients. In Le Molay, there was rain and athletics. The moment the sun came through, the men dashed for the field. The 5th Evac became the first unit to play softball on the continent. On the Fourth of July 1944, an impromptu show was put on. It was a great extravaganza, complete with mike and stage; there were sketches and songs by the Enlisted Men, and a “Dirty Gertie from Bizerte” presentation by a guest performer as well as a Ziegfield Follies revue by the organization’s own Nurses. Private First Class E. H. McCullough was awarded the Purple Heart the same day. It was in Normandy that the EM adopted a young pup which was quickly named “Calvados”, after a type of “soft” drink very popular in this region of France. A somewhat different form of beastie was “Oscar”, a short white duck, a creature of strange habits including a craving for Hennessey 90° proof cognac. The latter was short-lived but well-loved! It must be added that “Oscar” was followed by a quick succession of a wildlife – a pig, a goat, a few chickens, and even a cow (the last one was rather a neighbor and not a pet –ed). Past Normandy, the EM became dog-conscious again and found another dog which they called “Paris”.

The majority of the casualties arriving at the Evacuation Hospitals set up in Normandy were battle cases in need of immediate surgery. For example 894 patients out of the 1304 admitted by the 5th Evacuation during the first two weeks of operation in Normandy and all but 360 out of 3200 wounded treated at the 128th Evacuation Hospital Hospital (code name “Medicine 128”) were in this case, needing surgery. Fortunately many of the hospitals were reinforced by Auxiliary Surgical Teams in order to help control the patient influx during heavy combat conditions.

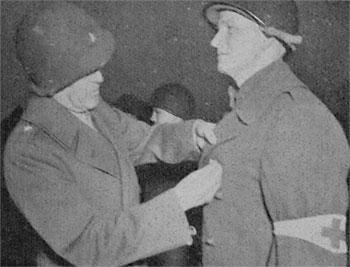

Awards Ceremony at Hannut, Belgium, 2 January 1945. Brigadier General John A. Rogers, Surgeon, First United States Army, awarded a number of Bronze Star Medals to several members of the 5th Evacuation Hospital.

The noise of battle gradually receded with the passing of each day. The days were long and not until 2230 hours did the shadows begin to fall. On 26 June 1944, a beloved Officer, Major Louis R. Way, was transferred to the 3d Auxiliary Surgical Group (code name “Meditation”) and all felt a deep sense of loss when he left the unit. During the period spent at Le Molay, the 5th treated 1304 patients, and after Le Molay, the hospital could proudly look ahead, and see the outline of their job with more clarity and plan accordingly. Precious lessons were learned everywhere and profitably applied.

On 11 July 1944, everyone moved to La Mine with the 2d Evacuation Hospital (code name “Medicine 2”) close to them. There were lots of mines in the area but these were soon cleared. Enlisted Men and some Officers sweated in the dark, stumbling over guy lines and nervously hammering at stakes and pins to set up the necessary hospital tents. At 0300 the work was called off because of darkness and the men, exhausted, dropped for some sleep. The next day, the hospital was swamped with patients and surgical teams poured in to assist. On 17 July 1944, the Adjutant noted the hottest day since the unit’s arrival in France. The same day, one of the most popular Officers in the 5th Evac, Captain Richard N. Duffy, Jr. left for the 3d Armored Division.

There was still considerable air activity around La Mine. A close-by antiaircraft artillery battery, firing at a German aircraft, dropped two shells in the hospital area, one landing in the EM area and the other doing considerable damage to the mess supply tent. Luckily no one was injured.

After St.-Lô fell (18 July 1944 –ed), the First US Army pressed forward and casualties increased dramatically. Planes were still active overhead and the personnel leaped out in steel helmets, crouching or lowering themselves to the ground to watch the show. Rain fell and gradually softened the grounds and soon bulldozers and steam rollers had to come in to help restore the site. On 25 July, Private Tony Vasquez, working at the laundry, was accidentally killed. The same day, the good news was that Major Frank H. Threlkel had been promoted to Lt. Colonel. A few days later, Captain Hayes W. Caldwell left the unit for a General Hospital.

During the last week of operation, the census increased considerably. A large scale Allied offensive was in progress as the unit was awakened early on 29 July 1944 by the noise of large numbers of planes overhead and the roar of friendly artillery fire. At midnight, the census stood at 410.

5th Evacuation Hospital Surgery personnel in action. Photo take during the organization’s second stay in Eupen, Belgium, January – March 1945.

On 3 August 1944, the 5th closed for receiving patients and the next day those that remained were transferred to the 2d Evacuation Hospital. That same day the 5th Evac actually took the field in combat. An unarmed reconnaissance team consisting of Captain James F. Bucker, 1st Lieutenant Jacques Cousin, Sergeant Sanford W. McGowan, Sergeant Thomas Taylor, and Private First Class Edgar H. McCullough went up to Mortain. They were welcomed by a volley of shots and shells and had to beat a hasty strategic retreat!

During the period that the unit operated at La Mine, a total of 2152 admissions were registered, and 1792 operations were performed. Only 46 cases had been bypassed. It was during that particular phase that the largest backlog was noted, almost 400. As no immediate evacuation was possible the organization simply had to buckle down and clean the slate.

The march to La Fortière was historic. Mines, mines, and mines, that was the area. Cerisy-la-Forêt was almost a total shambles, and passing through St.-Lô was difficult because of the mass of rubble. The road sides were heaped back with debris, stones, and broken-down houses, not one building seemed untouched by war. La Fortière was reached on 6 August 1944 but the hospital had to stand by waiting for the field to be de-mined by the Engineers. Pulling up to the area, the men were met by an old farmer and his family who ran out to meet their liberators. They were visibly moved and said they had been waiting almost four years for this day! The farmer offered Calvados and his little girls ran back and forth with fresh eggs clutched in their hands.

The hospital plant was soon set up and at 2030, 7 August 1944, the first patients were received. From then on the unit was swamped. Many extra surgical teams were brought in to assist. There was no Field Hospital out front and the 5th was the first link in the operative chain to handle the wounded and injured. The battle was still on, and the hospital was dangerously tucked away between friendly artillery and the front lines. One night a lone German plane was shot down over the area and the enemy pilot was carried in to die a few hours later in the hospital. It was in this area that the organization received its most severe casualties and experienced its highest death rate. By 9 August, the situation was critical. At midnight, everyone had been working solidly for 24 hours in the OR and there were still 15 chest and 14 abdominal cases to be done. Lt. Colonel Robert R. Stoner got in touch with the 3d Auxiliary Surgical Group, which was resting after busy days, and brought in teams, apparatus, and supplies, to quickly reduce the backlog. It was a hard and short phase for the hospital. Operations closed on 13 August, and while packing and loading of trucks took place, Headquarters’ phone jangled and runners scurried back and forth with orders and cancellations …It meanwhile continued to rain profusely. Then on 23 August 1944, the 5th Evac started its great “Victory Parade” through the towns of France, passing through Vire, Mortain, Alençon, Montagne, La Loupe, and halting at Senonches. Everywhere, the local population was on the roads with signs “Bienvenue à nos Libérateurs”. Each time the convoy paused, the men were assaulted with eggs, tomatoes, wine, and cider. Little girls offered flowers. After so many days in Normandy, marked by painful and wearisome experiences, and an absence of close civilian contact, it was intoxicating to march and drive through streets thronged with so many happy men, women and children. At last the sun made a timely appearance, pouring warmth and brilliance down dusty roads and crooked and narrow streets. The faces of these people beamed with spontaneous joy and gratitude. The 5th would never again witness such elation.

Photo illustrating a group of personnel pertaining to the 5th Evacuation Hospital, while stationed in Belgium.

The first long move came to an end bringing the hospital to Senonches (a medical concentration center –ed), a distance of 178 miles. The site which greeted the unit was however not one to stimulate an artist. The stubbles of wheat, still there, were embedded in mud for the greater part of the area. The essential tentage had been pitched, in fact, primarily the kitchen tent. After having fallen in and out of the chow line, the remaining tents were set up even tough the hospital was not to go in operation. Shortly after reaching Senonches there was a mass meeting of all personnel in an open field to learn about the tactical situation. Based on the situation it was evident that hospitals were unable to keep up with the rapid advance of the troops.

It was during the unit’s stay at Senonches that Paris finally fell, following numerous rumors that the city had surrendered. To celebrate the event, the local people turned out to welcome the 5th Evacuation (code name “Medicine 5”) and 96th Evacuation Hospitals (code name “Medicine 96”) with a municipal band, and civilians arrived in mass, obviously curious. Later, at Senonches, 18 American Red Cross Clubmobile girls stayed at the concentration area for a few days. They proved a most congenial group, offering donuts and coffee to a weary lot of medical personnel, and broke the monotony with real American music. Days passed quickly with grand tales of passes to Paris and softball games to keep the fighting and cheering spirit of the unit.

Some Statistics – 5th Evacuation Hospital

Le Molay – 1304 Admissions – 496 Operations – 0 Bypassed

La Mine – 2152 Admissions – 1792 Operations – 46 Bypassed

La Fortière – 1068 Admissions – 884 Operations – 57 Bypassed

By the evening of 6 September 1944, most of the unit was loaded for the great overnight move to La Capelle, and on to a new destination in Belgium. The distance represented some 208 miles in total blackout, in constant rain, which was completed by 0800 hours on 7 September 1944. The bedraggled group of men and women, numb from cold and cramped positions (this was a motor convoy –ed), limped off the trucks to a waiting meal of C-rations. Most of the day was spent battling the weather elements, while trying to pitch the necessary tents. By evening sufficient tentage had been set up to allow some rest and freedom from rain and wind. The new site was pleasantly surrounded and shaded with fruit trees, but rain prevented most outdoor activities. Because of the continuous eastward advance of the Allied Armies gas shortage became acute. Some days it was impossible to allow a mail truck to be sent out and delivery of supplies and rations required more time to come through. On 15 September, Headquarters was notified of another move. Arrangements were made and with a certain tinge of remorse the 5th Evac left La Capelle on 16 September 1944 for a new destination.

Belgium:

On 17 September 1944, the organization convoyed into the vicinity of Eupen, Belgium. The site was Herbesthal and tents were soon pitched in the rain and near dark. There were warnings about leaving the area, that hostile Germans waited in town to ambush any American troops. The great foe however, was really mud, mud of every kind, shape and form, mud that reached a depth of almost six inches. At times it was like walking through a field of discarded chewing gum. On 18 September, the first patients arrived and the next day they poured in. By 2400 hours, 347 patients had been admitted. Incoming trucks and ambulances had cut deep gashes in the roads and rain falling constantly had created pools everywhere that quickly filled with oaths hurled by weary litter bearers gingerly footing their way between the different wards. No moon, no stars, a perfect blackout, and a sea of mud everywhere. To leave the tent at night was more hazardous than facing the jungle.

There was no let up. Admissions on 19 September were equally high. On 21 September, a number of Engineers came in and cleared a road but the rain continued to fall and the mud quickly attained a new consistency.

On 22 September 1944, all were saddened by the news that Major Louis R. Way had been struck while working at the 41st Evacuation Hospital. He was cherished by the 5th for his deep devotion to his original outfit and Colonel Charles L. Baird went to visit him. The hospital was getting busier everyday. The mud still looked like dirty pea soup and remained. Fortunately some assistance was sent in the form of 35 German PWs who after joining, started digging ditches, and ate the mess chow with great relish. On 27 September a great event occurred; unheralded the hospital was visited by a stork and excitement ran high. A baby girl was delivered by caesarean operation and everyone in the ward forgot their problems concerning themselves mainly for the tiny new life that had suddenly been ushered in. Operation ended 28 September and the 5th Evac closed. There was a universal sigh of relief, as the census had been high, and the weather cold, raw, and damp, and it must be said that the prospect of indoor heat lifted the spirits and warmed the hearts. It was without regret that the unit rolled into Eupen, Belgium, to set up in buildings and for the first time since leaving Wokingham, England, the men were able to enjoy a few civilian luxuries. An advance detail had put the hospital building through a good conventional scrubbing before arrival of the main group.

Photo of Colonel Erling S. Fugelso, the new Commanding Officer of the 5th Evacuation Hospital, who replaced Colonel Charles S. Baird 6 March 1945. He would lead the unit into Germany.

By 4 October, the hospital and wards were quickly established in a five-story building with annex. A former Gestapo headquarters was to house the unit’s Headquarters and Officers. “Hotel Bosten”, a block away, was requisitioned for the Enlisted personnel and mess. Additional tents were pitched around the building to accommodate the remaining sections. Among some of the people in Eupen a note of hostility was soon detected, not everyone seemed happy with their liberators. After France the 5th felt like actors playing a new role. Notwithstanding, both staff and personnel were elated with the elegance of the mess hall, the warmth of the wards and rooms, the solid floors, the good chairs, and after enjoying a hot water bath, the 5th Evacuation Hospital was ready to confront the future.

Major General Paul R. Hawley, Surgeon General, ETOUSA, visited the hospital premises on 17 October 1944.

At the beginning the hospital acted as a transfer point. Most of the patients admitted were ambulatory and without delay they were sent on to the next installation. With the OR inactive the hospital could relax a little, but not all could avail themselves of this opportunity. Unfortunately the transition from field to indoors prompted an epidemic of colds. Social life improved, movies were organized, and passes obtained to visit Verviers, where the price of Belgian lace tripled in an hour, or Spa, and Liège. Personnel walked the streets of these cities with the purpose of finding something to send home. Passes came in for Paris, France. Expectations ran high as Thanksgiving and Christmas packages from home began to arrive, and it looked as if life in the ETO wasn’t so bad after all, many thought.

During reveille on 25 October 1944 a buzz-bomb (V-1 –ed) fell not far away. It sort of got the entire unit back into the war.

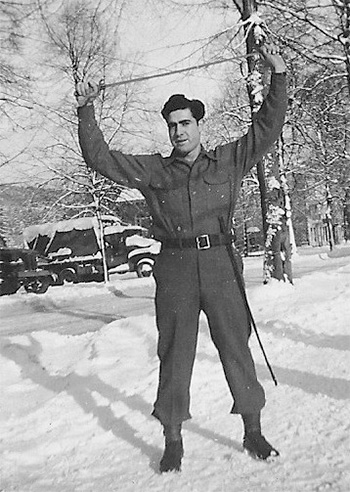

Photo of Michael Cecconi in the snow, Belgium, winter 1944.

The first snow of the season fell on the plant on 9 November 1944. By mid-November the organization was once more functioning as an Evacuation Hospital. Large numbers of casualties began pouring in, many from the fighting in the Hürtgen Forest and there was a first glimpse of trench foot cases. Additional tents had to be pressed into service. Everyone who was not immediately on duty became a litter bearer. Auxiliary surgical teams were called in, and with every table in surgery going at top speed the service personnel barely scratched the backlog. Central supply was moved from the outside tent which leaked badly, to the cellar of the main building which offered a better protection. The trouble however was, that it was flooded.

Then came Thanksgiving, with a meal (traditional turkey & fittings –ed) fit for a King! Early December 1944 was calm except for a truck gone AWOL. The spirit of Christmas was beginning to permeate all except for a German propaganda broadcast reporting on 11 December that Eupen was back in German hands. However, five days later, things began to change. On 16 December 1944 the hospital was awakened at 0530 in the morning by a blast which shook the entire building. Crashing glass brought the men up and while waiting in total darkness, hearing nothing but flashes and explosions, the building rocked again! A report arrived indicating that the operating room had been struck but that all personnel had left a few minutes before. Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men on duty remained, but all ambulatory patients were consigned to the basement and cellar. There was more noise but no further damage that night. Nevertheless, the Germans were now shelling (this was by artillery fire –ed) the area in and near Eupen where the 2d, the 5th and the 45th Evacuation Hospitals (code name “Medicine 45”) were established.

Meanwhile rumors began to fly, thick and fast. Enemy paratroops had been sighted everywhere, especially between Eupen and Malmédy. Reports were confused, and no one in the area had an idea how the battle was proceeding. Personnel nevertheless had to re-assure patients who were disturbed by the events. The Germans had launched a great counter-offensive in the Belgian Ardennes, with the aim to try and split the British and American lines and push through up to the Port of Antwerp (northern Belgium –ed). The next week was to be an anxious and troubled one for the 5th Evac.

It remained difficult to know what to believe, one day it seemed that Malmédy was reported fallen, the next day the troops had checked the enemy. Air activity was reminiscent of Normandy, and everyday enemy planes came over and were greeted with ack ack. On 16 December 1944 bombs were dropped but no direct damage done, the nearest miss being only a few yards away to the right of the bridge between the unit’s mess hall and the hospital building (with some damage to one of the operating rooms and the pharmacy –ed). On 20 December the hospital was simply swamped, and into an already overflowing plant 304 patients were admitted; a variety of sick patients, injured patients, and scared people. Receiving and pre-op became shock wards. Countless pints of blood were given. Surgery became a grim battlefield itself, but wounded and sick still came in, while the big guns pounded relentlessly day and night and the rain continued to fall.

Christmas Day was not unlike the rest, busy, noisy, with the usual visit from the Luftwaffe at lunch time. The ARC workers had placed small beautifully decorated trees in each ward and in the early morning visited and presented the patients with a small gift. The unit’s Chaplain conducted the Christmas services, with staff and personnel singing carols, and Santa visited the wards. There was an air of casual, tough not genuine, good cheer, throughout the hospital, and a fervent prayer on the lips of all, that the next Christmas would be celebrated at home (in fact the overall situation was tense –ed). At 1500 hours, 25 December 1944, all personnel was ordered to pack, it was time to leave, fortunately a good Christmas dinner was enjoyed by all. On 26 December another enemy bomb dropped close by causing only slight damage. The 5th Evac however would not leave before 29 December. On 30 December 1944, the group arrived in Hannut, Belgium.

Photo taken during the 5th Evacuation Hospital’s stay at Zülpich, Germany, March 1945.

Hannut looked like a Wokingham, Belgian style. It was a small peaceful Belgian village, with ample cognac if you knew your way around… For the first time on the continent the 5th was billeted in homes and cold. The hospital was set up in a “Pensionnat” (boarding school –ed) with one floor assigned to the Nurses. The dental clinic and dispensary were established in two empty stores, the Enlisted Men’s mess next to the “Hôtel de Ville” (town hall –ed) and the supply section in the suburbs. The Officers mess was in a café, and the bar was tended by a Belgian maid assisted by her ten-year old daughter. The brass ate in the back. It was a pleasure to retreat from the fuss of the hospital to enjoy the cordial society of the local civilian friends. At times staff and personnel ate with their Belgian friends and casually left behind cigarettes and rations. Long trails of kids often followed the men on PX days waiting for some chocolate. The hospital started operating from a Convent.

The organization had left Eupen on 29 December 1944 and it was no fun retreating. Everyone was anxious about the war. The news was good, but details rather meager. The radio was behind the news, and the Stars and Stripes several days behind the radio…

On 2 January 1945, through the snow-piled streets of Hannut, Belgium, Brigadier General John A. Rogers, MC, O-5931, Surgeon First United States Army drove by to pin the BSM (Bronze Star Medal –ed) on 1st Lieutenant Blackney, Sergeant William Bagshaw, Technician 4th Grade Hans J. Lowenstein, Technician 4th Grade Phillip Poltorak, Technician 5th Grade Frye and Private First Class Matthew J. Koster. That day the hospital buildings were scrubbed from top to bottom for the grand opening, the following day. 3 January a request came through for 60 EM to be placed on TD with the 97th Evacuation (code name “Medicine 97”) and 128th Evacuation Hospitals. This was not easy and the town had to be combed for these men, and by nightfall the headcount was only 45 and still 15 to be heard from. The 45 men already left that same night and the remaining personnel the next morning. On 4 January 1945, Captain Nathan Brody and Master Sergeant Francis H. Quigg were also awarded the Bronze Star Medal by Brigadier General John A. Rogers. The CO and his staff waited over an hour for the General. Snow, lots of snow fell and on 5 January a thick white blanket covered Hannut, Belgium. The next day a buzz-bomb landed in town at 0600, only two blocks from the Officers’ mess. The glass of many stores and houses was shattered. There was only one serious casualty, and 3 men (Ai F. Wong, Santos E. Liendro, and Sam Cassaro) of the 5th were injured, though not seriously. They were all awarded the Purple Heart. On 11 January nothing had happened and everyone was still waiting for the official opening; so the place was re-scrubbed. The 5th Evacuation Hospital finally opened 13 January 1945. Rain and snow fell intermittently. Few surgical cases were admitted that day. 22 January was a ‘special’ day as the first shipment of Coca-Cola was received. The next few days it was still cold, Mickey Rooney came over on 24 January and entertained. The operational period did not last long, as the hospital closed at the end of 24 January 1945. Next day the unit was back on the way to Eupen, having to leave many friends but keen to help wipe out defeat. It was still very cold and snowing when departing Hannut.

Things were pretty much in hand after the initial German breakthrough and so on 25 January 1945, the organization returned to Eupen (in the same setup), about ten miles from Malmédy, Belgium. At this time there was some quibbling about the selection of buildings in town for the different Evacuation Hospitals. One unit was given the opportunity of taking over the old school building the 5th had previously occupied, which they termed adequate for 50 beds only, not more. The CO then went over to First United States Headquarters at Spa and delivered a mighty line drive which shook everyone. The buildings fell back into the Colonel’s lap and with great gusto the personnel went about erecting tents everywhere. The roofs were once more prepared for the GC red cross markers. The Engineers went back to work and did a good job winterizing the tents. It gave the hospital a total bed capacity of 550, the greatest in the unit’s history.

Except for the ANC Officers, everybody was scattered about in billets, and it wasn’t too tough, as everyone seemed winterized and happy. Trench foot and frostbite however made their appearance once more.

Allied advances were made in the usual good style of crack Infantry and Armored Divisions, and while enemy terrain favored defensive warfare it did not stop American force, in spite of severe casualties. As usual the severity of the cases was in direct proportion to the bitterness of the fighting.

Once more the 5th Evac was ready to receive patients. The moment a patient arrived he was provided with good care. No time was lost in carrying the patient to receiving, as the floor space was limited, it had to be done fast, moreover the ambulances could not be detained. Cigarettes were dispensed, and coffee or water served. Friendly faces asked where the patients hailed from, donuts and crackers were distributed, and valuables checked and registered. Patients were then given a bath, their pulse was taken, and a first examination conducted.

Stations in Belgium – 5th Evacuation Hospital

Herbesthal, Liège Province – 18 September 1944 > 28 September 1944

Eupen, Liège Province – 6 October 1944 > 28 December 1944

Hannut, Liège Province – 13 January 1945 > 24 January 1945

Eupen, Liège Province – 27 January 1945 > 5 March 1945

On 28 February 1945, at 0830 hours, the unit lost its Commanding Officer, Colonel Charles L. Baird, who sustained a number of fractures when he fell through a roof while observing a fire nearby. All regretted to see him go. He was replaced by Colonel Erling S. Fugelso. The hospital closed 5 March 1945. Social activities had begun several days before with a concert at the “Hotel Bosten” with civilians attending. New furniture had patched up the Officers’ Club and the Enlisted Men gave a dance which proved a huge success. Passes to Brussels, Paris, and Spa extended recreational activities beyond the local limits.

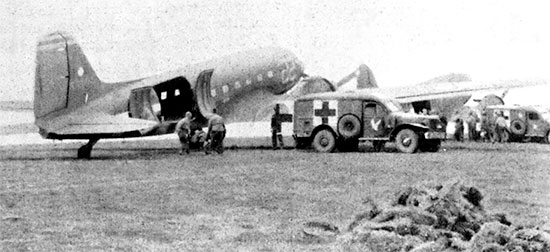

Ambulances of the 5th Evacuation Hospital delivering patients for air evacuation at Airstrip Y-71, near Eudenbach, Germany, early April 1945.

On 7 March 1945, American Armies crossed the River Rhine at Remagen (Ludendorff Bridge –ed) and established a bridgehead. On 9 March the 5th Evac moved to Zülpich, Germany, to medically support this action (also the 2d Evac Hosp was established in Zülpich –ed). At the time of the Rhine River crossing, 6 Evacuation Hospitals were open in support of the First US Army: the 5th – 44th (code name “Medicine 44”) – 67th (code name “Medicine 67”) – 102d (code name “Headlong”) – 103d and the 128th, with the majority of them concentrated in the rear of the bridgehead (the first to cross the Rhine was the 45th Evacuation Hospital –ed).

Some Statistics – 5th Evacuation Hospital

Herbesthal – 1720 Admissions – 819 Operations – 539 Bypassed

Eupen – 11469 Admissions – 2520 Operations – 3901 Bypassed (total number)

Hannut – 545 Admissions – 45 Operations – 0 Bypassed

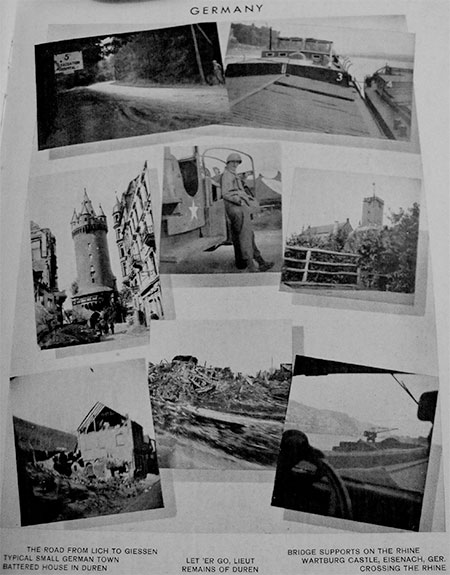

Germany:

Leaving many broken hearts behind, the organization left Eupen, Belgium, and entrucked for Zülpich, its first setup in Germany; enemy country. Little did the men realize that this was destined to be one of their most difficult operations of the war.

A Catholic Hospital for the mentally deficient was selected, the only unbombed building in the city, and work was started immediately. The first confronting task was to move some 600 patients, mostly old women. This was handled efficiently by 1st Lieutenant Grover C. Jackson’s men, assisted by a Polish detachment organized under Private First Class Tony Cardella’s supervision.

Michael Cecconi and fellow member, 5th Evacuation Hospital, in front of a 3/4-Ton, 4 x 4, Command & Reconnaissance Truck. Photo taken in Germany, spring of 1945.

The hospital opened at noon, 11 March 1945 with a 200-bed capacity. By the close of the first day, 152 patients had already been admitted, and expectations were not underestimated as the next few days became nightmares with the census reaching 525 patients, all received in only one day. Litter bearers worked around the clock as they carried their burdens up two, three, and four flights of stairs in the building. Life lost its meaning for the hard-working Surgeons, Nurses, Technicians, ARC workers, clerks and mess personnel. A snack bar was set up in an ante-room off the receiving section, where coffee and sandwiches were served to patients able to eat, and to bolster the spirits of the unit’s exhausted personnel. Day and night seemed one, and sometimes it looked as if the bravest efforts were futile in stemming the never-ending stream. The 5th was a beehive and in the corridors the German Nuns could be seen bending, scrubbing, and toiling over their own walls and floors.

During this phase the incoming patients assumed a motley character. The first recovered PWs of the 106th Infantry Division (captured in the Bulge –ed) came in and the personnel eagerly gathered around them, plying them with all sorts of questions as to their treatment by the enemy. Medical and Surgical Technicians followed them to the OR and maintained contact until the IV Pentothal had gently wafted them into dreamland. There were other RAMPs too, such as French and Belgian Prisoners of War, who had been held for over 4 years (following the 1940 German invasion of their country –ed) in Germany. But the men were also confronted to the broken down “Volkssturm”, old and unshaven men, who pathetically explained how the Wehrrmacht had laughed at them. The young boys of the “Hitlerjugend”, however, looked more arrogant and undefeated. It was a colorful array, becoming more varied as the hospital moved deeper into Germany. It was not realized that the unit would be supporting one of the most daring and offensive actions of the war in Germany, and the way to its defeat, the battle and capture of the Remagen bridgehead. As the battle pressed forward, it was difficult to follow the advance, and with operation becoming less heavy, orders were received on 23 March to close. All hoped for a rest, but the fortunes of war moved against this, and by 26 March 1945, the organization crossed the Rhine River.

Photo illustrating mixed group of Officers pertaining to the 5th Evacuation Hospital while stationed at Gotha, Germany, May 1945.

Leaving Zülpich behind, the 5th Evac crossed on a pontoon bridge at Bonn, Germany, the ancient University town, to set up in the vicinity of Eudenbach, near Airstrip Y-71, where it opened 28 March 1945. Upon entering the airstrip, the staff and personnel were met with almost total destruction of the installations and administrative buildings formerly occupied by the Luftwaffe. Already the frugal farmers living near the base were removing tiles and beams from the roofs to repair the damage done to their homes. Plans for the setup were made and everything was prepared for air evacuation. This would become the FIRST air evacuation to be in effect east of the Rhine. The Eudenbach operation was a difficult one because of personnel shortage. The 5th was the only Evacuation Hospital in this area as the 44th Evacuation Hospital (code name “Medicine 44”) had meanwhile (end March 1945 –ed) moved further northeast, leaving the field entirely to them. As there was only a minimum number of surgical teams, which was doing most of the work, the organization found itself shorthanded. Shifts of 18 hours were common, and as the men toiled on, numb with exhaustion, there was hope for some relief. Assistance was offered by the 115th Evacuation Hospital. The severity of the casualties resembled closely those admitted at Zülpich. Each day more and more Wehrmacht wounded poured in. RAMPs and DPs started filtering in from such countries as the United States, Britain, France, Belgium, Canada, and Eastern Europe. The hospital remained at Eudenbach for the entire period of fighting in the Ruhr pocket. At the time it even became necessary to use some of the available Field Hospitals as Evacuation Hospitals in order to keep pace with the rapidly moving combat troops. The strategic objectives were now first, to annihilate the German Forces in the Ruhr Pocket and effect the junction between the First and Ninth US Armies, and second, to contact Soviet Forces attacking in the east. To support these operations, 5 Evacuation Hospitals were opened east of the Rhine River. They consisted of the:

5th Evacuation Hospital > Eudenbach, Germany

44th Evacuation Hospital > Eudenbach, Germany

45th Evacuation Hospital > Bad Wildungen, Germany

67th Evacuation Hospital > Edingen, Germany

96th Evacuation Hospital > Gießen, Germany

By the end of April, the 5th Evac was among several of the US Army Evacuation Hospitals which would serve both the combat forces and the non-combatants. Thereafter, the unit was to aid and support transit RAMP patients at Gotha airfield, while the 45th Evacuation Hospital would become a temporary Station Hospital for the liberated inmates of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, near Weimar, Germany.

Nazi Germany was about to collapse, and rumors of peace circulated daily. Early May 1945, the unit moved down the Autobahn to another airfield near Gotha. R-4, a Supply & Evacuation Airfield, which had not only been an active Luftwaffe base but also contained aircraft assembly plants (in fall of 1943, the plants at Gotha in Thuringia were the largest German manufacturing units of twin-engine fighters accounting for 30% of the total production; they also produced major components and therefore became a valuable target for the US Army Air Forces –ed) had been taken over by the IX Engineering Command and made operational as of 11 April 1945. This area was in worse condition than Eudenbach. Wrecked and destroyed German aircraft were strewn about the bomb-pocked airfield. The large hangars were a mass of rubble, and it was hoped that it would not be long before the hospital could pitch its tents. The original plan had been to act as a Displaced Persons transfer point, but this was scrapped, although there was a DP camp nearby. The objective was now to be ready for reception and treatment of American and Allied casualties evacuated from the Soviet sector and to have the additional mission of supervising and feeding non-patient RAMPs awaiting air evacuation from the Gotha airfield. It was estimated that approximately 2000 westbound patients would be handled daily. It was further planned that personnel not required by any of the Evacuation Hospitals for completion of their mission, would be withdrawn and used for the care of RAMP, enemy PW, and DP patients. Soon the hospital opened for non-battle casualties, primarily Recovered Allied Military Personnel. The date was 5 May 1945. Following the liberation of Ohrdruf (the first German Concentration Camp to be liberated by US troops –ed), General Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered every citizen of Gotha to tour the camp and witness the Nazi atrocities. After visiting the camp, the Mayor of Gotha and his wife hanged themselves.

Stations in Germany – 5th Evacuation Hospital

Zülpich, North Rhine-Westphalia – 11 March 1945 > 23 March 1945

Eudenbach, North Rhine-Westphalia – 28 March 1945 > ????

Gotha, Thuringia – 5 May 1945 > 8 May 1945

Lich, Hessen – 5 June 1945 > ????

Group of administrative personnel of the 5th Evacuation Hospital at work, during the unit’s stay in Belgium.

Amid much confusion and rumors, the long-awaited day finally arrived; it was Tuesday 8 May 1945 and V-E Day! Relief was the prevailing emotion, and it must be said that little surprise attended the announcement – Victory at last! But soon, would come the next question, sung by the men: “Please, Mister Truman, when can we go home?”. In June 1945 the unit’s first high-pointers were readied for transfer home, and many men and women enjoyed leaves for Paris, the French Riviera, and the French Alps, while waiting for application of Redeployment measures. The same month the 5th Evac was sent to Lich, in Hessen, some 111 miles southeast of Gotha.

Some Statistics – 5th Evacuation Hospital

Zülpich – 3343 Admissions – 897 Operations – 1323 Bypassed

Eudenbach – 3945 Admissions – 1538 Operations – 1949 Bypassed

Gotha – Number of Admissions, Operations and Bypassed Patients, not available

Inactivation:

The 5th Evacuation Hospital was officially inactivated at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, on 5 March 1946. With regard to the postwar period it must be added that the unit was re-activated 2 October 1950 at Fort Bragg, North Carolina; re-organized and re-designated as the 5th Evacuation Hospital 12 June 1953; once more re-organized and re-designated as the 5th Combat Support Hospital 26 June 1972; and finally re-organized as the 5th Surgical Hospital 16 April 1982…

Personnel Roster (incomplete):

Officers:

| Allen, Clarence E. (Captain) | Baer, Louis (Captain) |

| Baird, Charles L. (Colonel) relieved of duty 6 Mar 45 | Baston, Frank D. (Lt Colonel) |

| Blackney (1st Lieutenant) | Benedict (1st Lieutenant) |

| Brown, Willis A. (Chaplain) | Brody, Nathan (Captain) |

| Caldwell, Hayes W. (Captain) transferred 28 Jul 44 | Bucker, James F. (Captain) |

| Cassels, Donald B. (Captain) | Canavan, Francis (Chief Warrant Officer) |

| Clowes, George A., Jr. (Captain) | Carrington, Hamilton K. (Captain) |

| Cuffney (Warrant Officer, Junior Grade) | Childs, George M. (Captain) |

| DeLeon, Fernando (Captain) | Cousin, Jacques (1st Lieutenant) |

| Farrington, Charles L. (Major) | Davies, David G. (Chaplain) |

| Foubare, Louis H. (Major) | Duffy, Richard N., Jr. (Captain) transferred 17 Jul 44 |

| Gradys, James N. (Chaplain) | Fugelso, Erling S. (Colonel) |

| Hadden, Frederick C. (Captain) | Gray, Harrison (1st Lieutenant) |

| Hochbaum, William J. (Major) | Helms (Major) |

| Hyman, Jacob G. (Major) | Howell, Otterbein C. (Chaplain) relieved of duty 30 Sep 44 |

| Jackson, Grover C. (1st Lieutenant) | Jaroszewicz, Anthony G. (Captain) |

| Johnson, David F. (Major) | Katz, Abraham (Captain) |

| Kelleher (Major) relieved of duty 13 Aug 43 | Kohn, Anthony (Captain) |

| Lavalle, Lawrence L. (Major) | Liepmann, Hans W. (Captain) |

| MacKercher, Peter A. (Captain) | Marian, Clifford F. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Mark, Jerome (Captain) | Marshall, Edward R. (Major) |

| Martinson, Edgar O. (Captain) | McColly, Edward B., II (Captain) |

| McHugh, Joseph W. (Captain) | McKenna, Stephen E. M. (Major) |

| Mihalich S. (1st Lieutenant) | Miller, Benjamin (Captain) |

| Mocko (1st Lieutenant) | Nelson, Victor (Major) |

| Petersen, Thure A. (1st Lieutenant) | Pietsch, Albert G. (Captain) |

| Porter, E. Lee (Major) | Ramp, Joseph V. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Reiner, David N. (Captain) | Richardson, Charles L. (Major) |

| Rolling (1st Lieutenant) | Shaheen, Gus S. (Captain) |

| Snell, V. (Lt Colonel) | Snyder, Oscar B. (Major) |

| Stark, Jack (Major) | Stoner, Robert L. (Lt Colonel) |

| Tainter, Eugene G. (Captain) | Taylor (Captain) |

| Threlkel, Frank H. (Lt Colonel) | Way, Louis R. (Major) transferred 26 Jun 44 |

| Weiner (Major) relieved of duty 24 May 43 | Weinstock, Harry W. (Captain) |

| White (Captain) | Zaris, David (Captain) |

Some ANC Officers pertaining to the 5th Evacuation Hospital.

Nurses:

| Anderson, Alice M. (1st Lieutenant) | Andrews, Sally (1st Lieutenant) |

| Baldwin, Ruth (Captain) relieved of duty 13 Nov 44 | Benedict, Rose B. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Blackney, Catherine A. (1st Lieutenant) | Boomgarn, Marie H. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Boone, Flonnie I. (1st Lieutenant) | Brown, Joan (1st Lieutenant) |

| Callen, Olga C. (1st Lieutenant) | Cassels (1st Lieutenant) |

| Clark, Lella, R. (1st Lieutenant) | Conklin, Regina E. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Craft, Vivian J. (2d Lieutenant) | Doty, Irene (1st Lieutenant) |

| Forrester, Dorothy C. (1st Lieutenant) | Fuller, Gola B. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Hall, Lulu J. (1st Lieutenant) | Harris, Elizabeth (2d Lieutenant) |

| Hartranft, Esther M. (1st Lieutenant) | Homola, Betty J. (1st Lieutenant) |

| King, Garnet L. (1st Lieutenant) | Laden, Esther (1st Lieutenant) |

| Lawhon, Jane (1st Lieutenant) | Louis, Jane (2d Lieutenant) |

| MacLean, Jean (2d Lieutenant) | Mansfield, Margaret (1st Lieutenant) |

| Melby, Harriette A. (1st Lieutenant) | Middleton, Mildred H. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Montagne, Dorothy N. (2d Lieutenant) | Neal, Annie L. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Neal, Ida F. (2d Lieutenant) | Nelson, Orpha (Captain) |

| Payne, Lillian D. (1st Lieutenant) | Perry, Eileen (1st Lieutenant) |

| Peterson, Carol D. (1st Lieutenant) | Rogers, Mary (2d Lieutenant) |

| Rolling, Dorothy (2d Lieutenant) | Schmidt, La Verna (1st Lieutenant) |

| Shepard, Mathilda R. (2d Lieutenant) | Smith, Allene S. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Stoudemire, Marie C. (1st Lieutenant) | Traughber, Elizabeth (1st Lieutenant) |

| Turner, Emma C. (1st Lieutenant) | Underwood, Frances (2d Lieutenant) |

| Vandiford, Susan L. (1st Lieutenant) | Wood, June A. (1st Lieutenant) |

| Wright, Katherine (1st Lieutenant) |

American Red Cross:

| Miss Dockhorn | Miss Hart | Miss Pate |

| Miss Raymer |

Time for recreation. Photo illustrating personnel of the 5th Evacuation Hospital enjoying a break and some free time, while off duty.

Enlisted Men:

| Abraham, Sidney (Pvt) | Acker, James A. (Pvt) | Anguillano, Michael R. (Pvt) |

| Arnold, Bentley | Baboska, Ed S. (S/Sgt) | Bagshaw, William (M/Sgt) |

| Barnard, A. G. | Batte, Willard O. (Pvt) | Baxter, Kenneth |

| Bearoff, Anthony J., Jr. (Pfc) | Belvin, Charles H. (Tec 5) | Bennett, George C. (Sgt) |

| Benson, Howard J. | Berardi, Dominick F. | Beutin, Howard O. |

| Bigelow, Thomas | Blanda, Michael (Cpl) | Bonforte, Rocco |

| Bower, Aloysius T. (S/Sgt) | Boyle, Robert L. (Sgt) | Brake, Raymond A. |

| Brand, Bernard (Pvt) | Brandenburg, Henry O. | Brodkorb, James |

| Brower, Richard (Pvt) | Brown, Ruben L. (Pvt) | Bryson, Paul (Pvt) |

| Bukowski, John H. | Bumbalough, John D. (Pvt) | Burdick, Bennie |

| Byrd, Thomas (Pvt) | Byrnes, Frederick (Cpl) | Campbell, Neil M. (Pvt) |

| Canavan | Cannon, Spencer | Cardella, Anthony J. (Pfc) |

| Cassaro, Sam | Castellucci, Dominick | Cavanaugh, Robert L. (Pvt) |

| Cecconi, Michael V. (Pvt) | Celich, Edward J. (Tec 3) | Charlesworth, Kenneth P. (Pvt) |

| Cherry, Arthur W. | Childers, Ewell (Pvt) | Christener, Roger A. |

| Christianson, Lawrence O. (Sgt) | Ciotto, Frank | Cipriano, Joseph (Pvt) |

| Clark, Hildreth M. | Collins, William F. (Pvt) | Cook, Charles |

| Cook, Wilbur (Pvt) | Corcoran, Martin (Tec 4) | Craft, Howard (Pvt) |

| Crosby, Elwood L. (Tec 4) | Czarnecki, Stephan (Pvt) | Czubowicz, Joe |

| D’Amico, Thomas (Pvt) | Davidson, Marshall | Davis, Erwin P. |

| Dawson, Burton C. | DeFina, Thomas (Tec 5) | DeLeon, J. G. |

| Dietz, Hugo A. | Discher, Robert | Donahue, Thomas G. |

| Donaldson, William J. (Tec 4) | Doty, Edward L. (Pvt) | Earhart, Monteith |

| Earomirski, Walter | Edwards, John W. | Eizikowitz, Leonard |

| Ellis, Roy | Emberry, Ray C. | Enos, Albert |

| Every, Frank M. | Falcone, E. J. | Farnsworth, Lerroy |

| Fischler, David | Fitz, Anton N. | Fitzgibbons, James F. |

| Fleming, Fred | Fletcher, Stanley | Forrest, Eugene R., Jr. |

| Frye (Tec 5) | Fullam, Donald E. | Garcia, Joseph |

| Gerhardt, Richard J. | Giuliano, Louis (Sgt) | Goldhaar, David |

| Goldheimer B. (Sgt) sent to | Goldman, Joseph A. | Gordon, Francis C. |

| OCS 22 Dec 42 | Graham, Carliss M. | Grant |

| Greer, Robert W. | Groat | Grogan, Kenneth J. |

| Groomes | Grunebaum, Leonard | Gungle, George W. |

| Hajohn, Andrew (Sgt) | Halpin | Hampton, Robert W. (Pvt) |

| Hanson, John W. (Tec 5) | Hardies | Harleman, Arthur C. |

| Hayes, Alvin (Tec 4) | Haynes, Marvin H. (Pvt) | Hearne, Maurice |

| Heck, Russell T. | Henderson, Joseph P., Jr. | Hernandez, Raymond J. |

Military Police patrol, somewhere on the road to Düren, Germany. See the 5th Evac Hosp sign (top left).

| Hewitt, Jack W. (Pvt) | Hillmann, Thomas M. (S/Sgt) | Hower, Aloysius F. |

| Huey, Edward C. | Jackson, Fred | Jacobson, Bernard O. |

| James, Elbert | James, Louis (S/Sgt) | Jennik, George |

| Jennings, Joe D. (Tec 5) | Jerrison, Herbert, Jr. | Karija, Stephen |

| Kelleher, Edward F. (Tec 5) | Kenney, Francis L. | Kightlinger, Frank (Sgt) |

| Knapp, Charles | Knapp, William | Koletzko, Paul |

| Korwin, George (S/Sgt) | Koster, Matthew J. (Pfc) | Kroeger, Oswald M. |

| Lakiotes, George P. (Pvt) | LaMarde, Joe | Lato, Joseph (Pvt) |

| Leahey, John P. (T/Sgt) | LeMay, John C. | Levesque, Edward J. |

| Lewis, Edward F. (Pvt) | Liendro, Santos E. (Pvt) | Linden, Andrew (Pvt) |

| Locates, Linwood (Tec 4) | Lopez, John J. (Sgt) | Lovett |

| Lowenstein, Hans J. (Tec 4) | Luhmann, Arthur (Pvt) | Maher, James L. |

| Malone, Francis X. (Tec 3) | Maloney, Thomas (Pvt) | Mancini, Nick |

| Manishefski, Morris | Manning | Mannino, Rocco J. |

| Marshall, Edward L. | Mascolino, August | Maxwell, Merritt C. (Pvt) |

| McCarthy, Paul | McCord, William T. | McCullough, Edgar H. (Pfc) |

| McGowan, Sanford W. (Sgt) | McIntyre, Otis (Pvt) | McKinley, John H. |

| McLaughlin, Ray J. (Pvt) | McMahan, James F. (Pvt) | McNeill, Edwin R. (Tec 4) |

| Melton, John F. (Pvt) | Methvin, Albert R. (Pvt) | Migirditch, Peter H. (Pvt) |

| Misczak, Walter | Mulrooney, Stephen (Tec 4) | Naroff, Charles (Pvt) |

| Nelson, Milton C. | Niemela, Carol Q. (Pvt) | Nitzschke, Lloyd E. |

| Nye, Arthur (S/Sgt) | Owens, Omar | Oxfeld, Dave (F/Sgt) |

| Pait, Theron B. | Palen, Robert (Pvt) | Parisi, Frank R. |

| Pasquale, John J. | Pearce, Albert E. (Pvt) | Pedigo, Victor L. |

| Peterson, Thure A. (Cpl) | Petitsky | Pittmann, John W., Jr. (Pvt) |

| Podraza, Stanley A. (Tec 4) | Poltorak, Phillip (Tec 4) | Poniske, Richard A. (Pfc) |

| Porter, Clifford H. (Pvt) | Pratt, John J. | Prebonich, Frank M. |

| Press, Louis | Pritchard, Walther D. (Pvt) | Puzin, Michael J. (Pvt) |

| Quigg, Francis H. (M/Sgt) | Raan, Sal J. | Radel, Robert J. |

| Rago, Sal J. (Tec 5) | Rainbolt, Clarence M. (Pvt) | Red, Cecil (Tec 4) |

| Rediger, Nelson C. | Regar, Alonso E. | Reilley, Leo A. |

| Renew, Rudell | Richey, Glen H. | Rietveld, Lester R. |

| Rodgaard, Arnold | Rodriguez, Bernardo | Rogers, Fred (Pvt) |

| Roller, Delbert L. (Tec 5) | Sabo, Mike (Tec 4) | Saccoman, Thomas (Cpl) |

| Sais, William (Tec 3) | Samico, Thomas (Tec 5) | Sanders, Ted (Pvt) |

| Sarlouis, Bernard (Tec 3) | Sass, Charles (Pvt) | Schloss, Herbert (Pfc) |

| Schmeidel, William I. | Schneider, Raymond | Schuh, Ernest |

| Schutz, William (S/Sgt) | Sellers, James M. | Shilt, Amos (Pvt) |

| Shor (Sgt) | Short, Ronald L. (Tec 5) | Shortall, Robert F. (Pvt) |

| Siebzehner, Hirsch | Simpson, Joseph (Pvt) | Simpson, Robert E. (T/Sgt) |

| Singleton, Grady (Pvt) | Slider, Kenneth (Pvt) | Smith, Robert L. (Pvt) |

| Snitowski, George (Pvt) | Soeder, Robert G. (M/Sgt) | Spencer, Lloyd F. |

| Spice, Leon (Pvt) | Starner, Carl | Stephany, Roman |

| Stone, Cleatus L. | Taft, Julian L. | Tait, Kenneth D. (F/Sgt) |

| Taylor, Thomas (Sgt) | Temple, Eddie | Thillmann (Sgt) |

| Thomas, Russell S. | Thompson, Buryl E. | Thompson Douglas O. |

| Thompson, Harold | Tierney, George | Treat |

| Twidwell, William | Uphoff, Walter C. | Vasquez, Tony (Pvt) killed 25 Jul 44 |

| Veltri, Jack (Sgt) | Vicino, Joseph | Vitella, Frank (Mess Sergeant) |