39th Evacuation Hospital Unit History

Booklet on Camp Atterbury, Division Training Camp. The official designation of “Camp Atterbury” was announced by Congress 26 February 1942, with activation effective 2 June 1942.

Introduction & Activation:

The 39th Evacuation Hospital was activated by Special Order No. 85, dated 16 July 1942 (War Department Letter 320.2, dated 14 July 1942, ref MRM-M-GM), as part of the Second United States Army with Headquarters in Memphis, Tennessee, on 19 July 1942. It was placed under the administration of Colonel Richard Stickney and the 8th Headquarters Detachment, Special Troops, stationed at Cp. Atterbury, Columbus, Indiana (this new Division Training Camp was officially announced by the W.D. on 14 January 1942 with excavations commencing a month later. Its name, Camp General William Wallace Atterbury was officially announced by Congress 26 February 1942 and confirmed by General Order No. 12, dated 6 March 1942. Labor disputes, material shortages, hindered construction progress. On 30 May 1942, Colonel Welton M. Modisette was confirmed as C.O. of Cp. Atterbury, and one of the first units assigned for training at the camp became the re-activated 83d Infantry Division. Cp. Atterbury was officially activated on 2 June 1942 –ed).

Lt. Colonel Allen N. Bracher (28 January 1906 – 25 November 1989), WW2 Commanding Officer, 39th Evacuation Hospital.

The first Medical Officer arrived at Cp. Atterbury 18 June 1942. The Camp was now about 60% complete, with new buildings and roads being constructed, street signs being erected, fire ranges being developed, and while construction was still running, first troops were already due for training. The first Dental Clinic opened 1 August 1942. The first contingent of 39th Evacuation Hospital personnel arrived at the Camp on 8 August 1942. Due to a temporary strain in resources, the 39th Evac Hosp was in fact not officially activated until 11 August 1942. This took place under First Lieutenant William E. North and his group of 47 enlisted cadres from the 26th Evacuation Hospital. They were initially to set up the Hospital’s quarters for the men and women who were on their way to join the new unit. Lieutenant W. North remained in charge until the arrival of Lt. Colonel Allen N. Bracher, MC, who would command the Hospital unit for almost the entire WW2 period.

Training:

Mobilization Training officially began on 11 September 1942 under Lt. Colonel Clinton Adams. Newly enrolled enlisted members of the United States Army first learned the basics of military life, as per FM 21-100 the “Soldier’s Handbook”, distributed to the individual EM as a convenient and compact source of basic military information. Military discipline and courtesy were later followed by specific programs involving tent packing, tent pitching, tent loading and transportation, which inevitably would lead to successfully moving an entire hospital in the field. As training went along, the necessary medical skills and techniques were now also focused, as it was essential that the life-saving operations needed to be learned as well. A number of doctors were therefore sent to attend classes at Wakeman General and Convalescent Hospital, at Cp. Atterbury (the US Army’s largest convalescent medical facility during WW2 –ed). On 28 September, the 39th received 14 critically-needed Medical Technicians, and one week later, 58 Replacements arrived directly from Cp. Barkeley, Abilene, Texas (Medical Replacement Training Center –ed). On 27 November, another 123 men were assigned to the Hospital after having gone through training at Cp. Joseph T. Robinson, Little Rock, Arkansas (Infantry Replacement Training Center –ed). The very first phase of Field Exercises took place in December and this proved the only way to learn to properly set up a hospital in the field. Briefings and reports were conducted to show weaknesses and discuss corrections and improvements. Day and night marches were organized. After celebrating Christmas with a traditional dinner at the camp, New Year’s Eve was spent in a most unusual way by holding an evening march which lasted until midnight. 1943 would become a year of challenges and growth for the 39th Evacuation Hospital. On 1 and 2 January 1943, the unit had extensive Field Exercises, and on 6 January 1943, Lt. General Ben Lear (CG > Second United States Army, 1879-1966 –ed) inspected Cp. Atterbury during which the 39th Evac participated in its first military morning parade. After the General’s inspection tour, the Hospital had a dry run on mess and sanitation installations, indispensable during operations in the field.

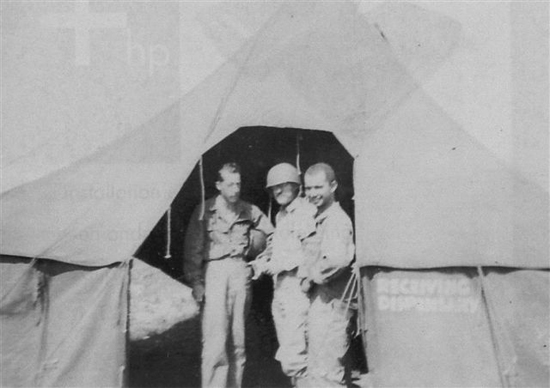

Picture taken during field exercises and maneuvers in the Zone of Interior 1943. One of the men is wearing the shoulder sleeve insignia of the Second United States Army.

On 12 January 1943, Colonel C. Adams was reassigned to command the 41st Evacuation Hospital (activated 1 June 1941, supplied enlisted personnel for affiliated units, embarked for England 13 November 1943 –ed). He was replaced by Lt. Colonel Allen N. Bracher, MC (CO > 39th Evac Hosp), who transferred from Cp. Edwards, Falmouth, Massachusetts (Antiaircraft Artillery Training Center –ed), after serving 8 years in the Army. On 22-23 January, the Hospital participated in a combat field test in support of the 83d Infantry Division. The 2-day field exercise was deemed successful, and the unit passed with flying colors. The unit was ready to start the second phase of Field Exercises, including spending a large number (8 to 10) of weeks in the field, consisting of numerous marches, bivouacs, moves, and particular skills, such as pitching tents in the dark and treating mock patients the correct way. This culminated with a complete obstacle course taken by everyone. On 18 February, the 39th Evacuation Hospital started a week-long bivouac; the program was intended for the unit to learn how to sustain itself in the field away from a well-established base. Officers from the 44th Evacuation Hospital (activated 30 August 1942, embarked for England 16 November 1943 –ed) visited the 39th on 22 February and were impressed by the general setup. Despite frequent rains and mud, field hikes and more bivouacs followed throughout March and April. The third and final phase of Field Exercises started on 19 April 1943. Its aim was to prepare all units for regular deployment and overseas movement. Tactical measures were studied, loading and unpacking exercises were conducted, simulated gas attack defensive measures were rehearsed, bivouacking and moving took place, and night marches were organized. Some special event took place at the camp on 30 April with arrival of the first Axis PWs, 760 Italians who had been captured in North Africa. Aircraft demonstrated bomb runs and strafing techniques on convoys, movements took place under black-out conditions. Part of the extensive field exercises was meant to prepare the units for the Second Army Tennessee Maneuvers. At the end of May 1943, each member of the 39th was required to run Cp. Atterbury’s infiltration course, this would help determine whether the Hospital was ready for active deployment to the field.

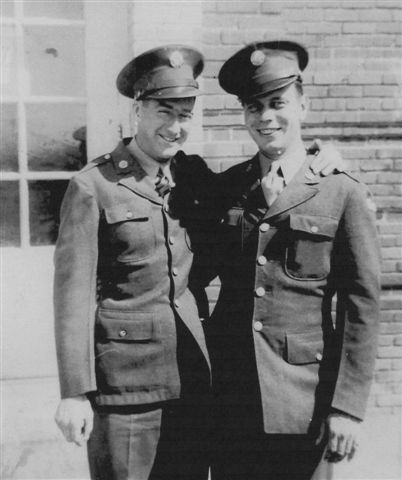

Picture taken stateside in 1943. Private Roy W. Kyllander (service 15 September 1942 – 19 November 1945) with buddy. Both soldiers are still wearing the SSI of the Second United States Army on their service coat.

On 7 June 1943, the 39th Evacuation Hospital left Cp. Atterbury on its way to the Tennessee Maneuvers. Everyone got busy preparing and packing the hospital equipment for shipment by rail. On 13 June, an advance party led by Lt. Colonel Arthur A. Brown, MC (XO > 39th Evac Hosp), assisted by one EM traveled to Indianapolis to make arrangements for the journey. The next morning, the Hospital convoy lined up and by 0620 it was on its way. Training was now officially over and it was time to practice. During the Second Army No. 2 Tennessee Maneuvers, the 39th would be located at Shelbyville, approximately fifty miles south of Nashville, with a later move to another location, twenty miles northeast of Beechgrove. In the middle of the maneuvers, the 39th received the majority of its Nurses’ complement. 16 Nurses under the command of Chief Nurse Dorothy Maxson, ANC, arrived on 16 July followed by some more on 17 July, which enabled the unit to reach its quota of 20 ANC personnel. Early August 1943, the Hospital was instructed to relocate in the vicinity of Blessing. Meanwhile, Major John J. Scanlon, MC, had taken over as new Executive Officer. On 13 August, Chaplain George J. DeWitt, joined the unit. When the opening phases of the Tennessee Maneuvers were completed on 27 August, the 39th had made a total of 5 moves during the first phases, and it was only after having carried out the last one, that the personnel received official leaves and furloughs. In October, the necessary time was reserved to winterize the hospital equipment, this was achieved with the help of the 44th Engineer Battalion. During the long maneuvers, the unit was often in contact with other medical units, or received visits from parties belonging to other Hospitals (such as the 44th Evacuation and the 107th Evacuation Hospitals). On 20 December 1943, the Hospital closed, packed and loaded all its tentage, and moved in convoy to Cp. Forrest, Tullahoma, Tennessee (Infantry Division Camp –ed). The move required all the unit’s vehicles and could only take place after borrowing 35 ambulances from another medical unit. 25 December would be the second Christmas spent in the Zone of Interior. In the afternoon, the Enlisted Men held a small party in their barracks, while the Officers and the Nurses celebrated on their own in the Officers’ Day Room. Once all festivities were over, it was time to prepare for the expected move overseas.

Medical personnel of the 39th Evacuation Hospital in front of the Receiving Dispensary. Picture probably taken during the Second United States Army No. 2 Tennessee Maneuvers in June 1943.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

All Hospital equipment was inspected once more and while the 39th Evac was waiting for marching orders, Colonel A. N. Bracher (1906-1989 –ed) ordered a series of marches to keep personnel disciplined. To keep everyone busy and their skills honed, the men were instructed to set up a 16-tent Hospital on 31 December, followed three days later by another 15-mile march in severe cold. On 5 January 1944, the unit did a black-out convoy, and on 8 January, another 18-mile hike took place. A few transfers were organized, and the requisition for enlisted personnel was completed with the arrival of a new contingent from the 87th Infantry Division. 6 more Nurses were assigned on 13 January. Before the Hospital moved to New York harbor, it first transferred for a temporary stop at Cp. Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey (Staging Area for New York Port of Embarkation –ed) which began by rail at 2345 on 1 February 1944. During its stay at Cp. Kilmer, the Hospital doctors were available at the NY P/E Hospital just in case anyone would need a last minute medical intervention before the journey overseas. Enlisted personnel were invited to view training films, to attend lectures, to have physicals, and to undergo one last gear and clothing inspection. Orders were received 6 February. The transport vessel for the Atlantic crossing was the “HMS Andes” (British troop transport). After a stay of five days at New York harbor, the 39th Evacuation Hospital was on its way to the European Theater of Operations.

Booklet on Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey. This was one of the Staging Areas for the New York Port of Embarkation (troop capacity 2,074 Officers & 35,386 EM).

United Kingdom:

On the morning of 8 February 1944, the 39th embarked on the “HMS Andes” (the vessel left New York P/E on 9 February carrying many US troops bound for the E.T.O., such as the 203d Antiaircraft Artillery (AW) Battalion, the 635th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and the 1195th Engineer Combat Group –ed) for a 9-day overseas journey to the United Kingdom. Officers rode in style as they were assigned staterooms, the Nurses got excellent quarters, but the Enlisted Men were sent to the hold where they were either to sleep in bunks or in hammocks. At first there was some speculation as to the ship’s destination, some thought it would be Africa. Soon everyone knew that the Andes was on its way to the British Isles where the Hospital would prepare, together with other American units, the largest invasion force to strike against Nazi-occupied Europe. Traveling was under strict blackout conditions and a continuous zigzag path was followed throughout the voyage. Rough seas were encountered, more vaccinations were received, boredom set in, British food was awful, and as the ship got closer to European shores, the weather grew colder. Early on 17 February, crew members and passengers spotted the British coast. The transport headed for Liverpool, but due to the large number of vessels in the harbor, “HMS Andes” had to wait another day before being able to dock. The ship finally docked at Liverpool around 2100 on 18 February 1944. Two hours after docking, the Hospital equipment was unloaded from the ship and the 39th began their stay in Britain.

The unit marched to the nearby railway station in the middle of the night. After entraining, the trip went to Altrincham (borough of Trafford –ed) which was reached the next morning. At a place called Hale, the unit received hot coffee and donuts served by the A.R.C. which also provided straw mattresses to sleep on until equipment was available and beds could be assigned. For the next four months, the 39th Evac Hosp would stay in Altrincham, where they joined the 34th Evacuation Hospital and the Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment, 64th Medical Group (first attached to First, then to Third and later to Ninth United States Armies –ed). After unloading the “HMS Andes”, all the EM, Officers and Nurses were billeted in English homes. Food and lodging were provided, but a certain adaptation was necessary as fuel for stoves and hot water were scarce, food habits were different, and there was rationing in war-torn Britain. On 24 February, the Hospital learned that it would be attached to VIII Corps (to eventually become part of Third United States Army –ed). On 26 February 1944, all unit members attended a required indoctrination lecture given to US Forces stationed in the United Kingdom (customs, civilian and military organizations, bomb reconnaissance and disposal, VD hazards, and much more).

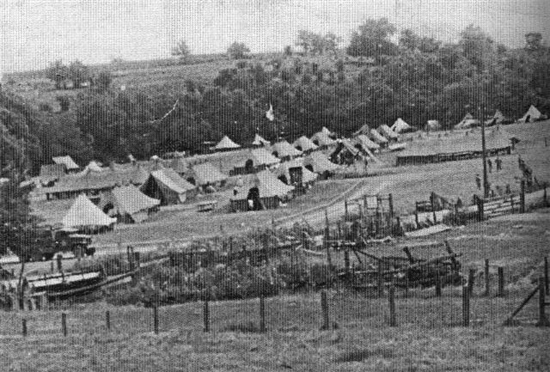

Installations of the 39th Evacuation Hospital at Beechgrove, Zone of Interior. Picture taken in June 1943.

During the month of March, the 39th went on its first hike in the English countryside, recreation was provided with volleyball and softball, men and women learned to ride bicycles to tour the country, personnel was sent on DS with other Hospitals, such as the 91st Evacuation Hospital and the 120th Station Hospital. Inspections were carried out by both VIII Corps Medical Officers and Third Army Headquarters representatives. One way of learning was to visit other Hospitals who had gained some battle experience during the North African campaigns. On 12 April, additional supplies reached the Hospital from several depots throughout Britain. Crates and cases had to be opened, checked for contents, catalogued and identified for use in the field. 14 April 1944 was a very special day for the 39th as it was to participate in its first formal parade in the E.T.O. Since the Invasion was drawing nearer, Third United States Army cancelled all leaves and furloughs. Further conferences, briefings, and lectures were attended as well as visits to other Hospitals to learn, improve and adopt other skills and techniques. On 17 May, the C.O., Colonel A. N. Bracher alerted the unit to prepare for movement to the continent.

On 24 May, the Hospital unit moved to Devonsdale Park to participate in a series of training exercises (it would have to wait until after the beachheads were secure to cross over to the continent, anyway Patton’s Third Army was not supposed to become operational on the continent until 1 August 1944 –ed). This period was put to good use to test and practice evacuation procedures and other field problems which might arise with medical organizations. When not busy packing and unpacking medical supplies, Enlisted personnel and Nurses were able to attend dances, visit pubs, and tour London and Manchester. End May Lt. General George S. Patton, Jr. met with the staff of the 39th Evac Hosp in Moberly Hall, explaining his strategy of war and stressing the fact that Hospitals were needed to remain close to the frontlines in order to support the soldiers in his command. The occasion certainly proved to be a most memorable meeting to all Officers who attended.

Sign of the 39th Evacuation Hospital.

France:

As soon as the Invasion had taken place, the 39th was waiting to move across the English Channel for the continent. Some of the hospitals assigned to the First United States Army were now supporting the troops that had already landed. Over the next few days, the unit received additional equipment and tentage. Many Nurses spent hours preparing linings for the new ward tents. The necessary vehicles were received. On 16 June, the Nurses returned from training at the 186th General Hospital. Meanwhile the unit staff increased and Officers and Nurses continued with additional classes. Some of them who had been on DS with other units (such as the 312th Station Hospital) were now returned to the 39th.

The Fourth of July went by without celebration and by 8 July, the Hospital was all packed and ready for the journey to France. Marching orders were received on the morning of 13 July 1944 with instructions to entrain for Southampton. The next day, the men and women of the 39th Evac woke up early and prepared to move to the marshaling area, where they were grouped and received French “Invasion” currency. 3 Officers and 54 EM then traveled from the marshaling area to the docks in order to load all the unit’s vehicles and equipment onto several Liberty ships. On 15 July, the advance party boarded one of the ships and headed for Normandy. This first group weighed anchor at 0430 in the morning, and was only allowed to disembark at Utah Beach at 2000 the same day. The next day, both vehicles and equipment were unloaded and transferred onto landing craft which took them to “Transient Area B”. Military Police escorted the party to their bivouac area. On 17 July, the remainder of the Hospital boarded Liberty ships and headed for France. The Nurses were on a separate vessel, while the men embarked on a LCI. As the beach was overcrowded, the troops had to wait to disembark. Finally they were allowed to land after having a quick dinner of K-Rations. The equipment was unloaded on the beach by 2000, and was then loaded onto several cargo trucks for further transportation inland. Officers collected the men and marched them eight miles to Transient Area B. The Liberty ship with the unit’s Nurses arrived shortly after the men started their march, but the ladies were moved in trucks to the area. That night, everyone had to sleep on the ground with just a single blanket for cover. Not only was the night cold, but war planes continuously flew overhead all night keeping many soldiers awake. The 39th Evacuation Hospital was temporarily attached to First Army Headquarters.

Tec 5 Roy W. Kyllander with friend in front of one of the 39th EH’s two 3/4-ton Dodge WC-54 Ambulances.

On 19 July, trucks arrived at the Transient Area to transport the Hospital unit to Bricquebec. The convoy left at 0145, early in the morning, so it could travel under concealment of darkness. Upon arrival, the men were ordered to set up tents and erect the Hospital. However, the unit was hardly in place when orders arrived from First United States Army to relocate; it was ordered to relieve the 96th Evacuation Hospital (landed at Utah Beach on 16 June 1944 –ed) near Ste-Mère-Eglise which had been busy treating patients injured from D-Day to the first break-out operations. Quickly packed, the Hospital moved forward reaching the selected site, setting up its tents directly next to the 96th Evac in an open field on the outskirts of town. Many dead bodies, both German and American, still covered the ground and the smell of death was still around. 21 July 1944 was the 39th Evac’s official opening in France, and personnel now got their first opportunity to treat real combat victims. The majority of patients were transfers from the 96th Evac Hosp (which left the area on 22 July –ed). In total, 96 patients were admitted that day. Later, an auxiliary surgical team joined the unit to help with the scheduled surgical operations. The Hospital stopped admitting patients on 25 July. All equipment not critically needed was then packed for transportation. Colonel Bracher learned that his unit might not continue with First Army; it might just head elsewhere with Patton’s Third Army instead.

The 39th lost its first member, when Second Lieutenant Burlah Barkley died after aspiring vomiting caused by stomach convulsions (he was buried at Blosville cemetery). While the unit was still waiting for instructions to relocate, it was visited by Colonel Walker, C.O. of the 77th Evacuation Hospital (affiliated to the University of Kansas, activated 10 May 1942, embarked for England 5 August 1942, and after landing at Utah Beach, set up near Ste-Mère-Eglise on 15 June 1944 –ed). After activation of the Third United States Army (1 August 1944 –ed), the 39th Evacuation Hospital was attached to it. It would remain part of TUSA for the duration of the war.

The 39th Evacuation Hospital, near Arrou, France. Picture taken in August 1944. Courtesy Pascal Bulois.

Medical Units attached to Third United States Army during operations in the E.T.O., dated 1 August 1944

6th + 7th + 8th Convalescent Hospital

12th + 32d + 34th + 35th + 39th + 100th + 101st + 102d + 103d + 104th + 106th + 107th + 108th + 109th Evacuation Hospital

16th + 30th + 48th + 53d + 54th Field Hospital

64th + 65th + 66th + 67th + 69th Medical Group

4th Auxiliary Surgical Group

34th + 37th + 107th + 167th + 168th + 169th + 171st + 172d + 173d + 174th + 240th + 427th + 436th + 437th Medical Battalion

92d + 94th + 95th Medical Gas Treatment Battalion

383d + 548th + 573d + 580th + 581st + 584th + 585th + 586th + 587th + 588th + 589th + 590th + 591st + 593d + 594th + 595th Motor Ambulance Company

610th + 613th + 614th + 623d + 635th + 647th + 648th + 650th + 659th + 664th + 666th Medical Clearing Company

428th + 429th + 431st + 432d + 433d + 434th + 435th + 436th + 437th + 438th + 439th + 461st + 462d + 465th + 494th + 495th + 496th Medical Collecting Company

32d + 33d Medical Depot Company

7th Medical Laboratory Company

At 0300 hours, 1 August, the 39th reached the town of St.-Sauveur Lendelin on the western edge of the Cotentin Peninsula. Transportation had been provided by the 103d Evacuation Hospital (temporarily transferred from the Third to the First United States Army –ed) and the 437th Medical Collecting Company. Upon arrival at an empty field, Officers, Enlisted Men and Nurses were exhausted, but since there was no accommodation, they all had to sleep in the open. Reveille was sounded at 0500 and after having eaten a small and quick breakfast the Enlisted Men started setting up the Hospital tents in a cross arrangement. The facility was opened at 0730, and soon afterwards the first patients started coming in. Strangely, most of the day’s 77 patients were wounded German PWs. On 2 August, fighting around Avranches intensified, and despite roaming enemy planes above American positions, the Hospital continued to operate, receiving 125 patients that day. The flow of incoming cases was such that the 39th had to stop admitting patients at 1000 hours and divert the others to the 32d Evacuation Hospital (another Hospital transferred from the Third to the First United States Army –ed). To help deal with the influx of wounded, 2 surgical teams pertaining to the 104th Evacuation Hospital (also temporarily transferred to the First United States Army –ed), men from the 106th Medical Clearing Company, and 5 ambulances from the 587th Motor Ambulance Company were temporarily attached to the 39th. Cases requiring further evacuation were transferred to the Biniville airstrip (Advanced Landing Ground A-24C –ed). On 3 August, the Hospital admitted 106 patients, among which many victims of landmines or booby-traps, which required amputation. To help with this ghastly surgery, the 39th allowed 5 of the German PWs to help with the wounded; a German Captain named Jansen and 4 of his medical Officers worked along well with their American counterparts. On 14 August, the 102d Evacuation Hospital (unit temporarily transferred from the Third to the First United States Army –ed) opened southeast of Granville, and relieved the 39th Evac of its heavy workload. Men could now relax and enjoy some entertainment provided by VIII Corps, which sent a USO show. On 8 August, elements of VIII Corps were closing in on St. Malo (liberated 17 August 1944 –ed) and since it was too far to transfer the wounded back to the 39th, the unit was told to stop receiving patients and pack up for relocation. Colonel A. N. Bracher took the Hospital through Avranches up to Vitré. Additional vehicles were borrowed from the 102d and 104th Evacuation Hospitals and all non-transferable cases were sent on to one of the Platoons of the 610th Medical Clearing Company. On 8 August, the unit left in a convoy for Vitré where it arrived unscathed after a 104-mile stretch. It was 0730, and after a quick breakfast the men started setting up the necessary tentage. By 1100 hours, the Hospital was ready to accept patients; however, the day was relatively quiet as only 7 wounded men came in. The morning had remained quiet, but from the afternoon on, scores of ambulances streamed into the Hospital, which became filled with patients. As there was no more capacity to put the wounded, many of them were set on the ground outside the O.R. on litters. Since it was hot, the August sun beat down unmercifully on the wounded soldiers, a group of EM quickly erected some tarps to protect the patients. Doctors and Medical/Surgical Technicians worked frantically to treat the most serious cases first. Among the patients were German infantrymen who had been wounded during the battle for St. Malo. As additional patients continued to arrive, the Hospital admitted over 480 patients before midnight. In order to cope with so many cases, the capacity was increased to 650 beds. Folding cots and litters were therefore borrowed from the 6th Convalescent Hospital (another TUSA unit –ed). They came in very handy, as the Hospital overflowed when 200 new patients were admitted. It became so busy, that at one point during the day, there was a backlog of 320 patients. A record was achieved when surgeons performed 124 operations in a single day. On 11 August the C.O. decided to accept critical cases only, and all other patients had to be directed to other Evacuation or Field Hospitals. Thanks to the efforts of all in the 39th and with the help of two extra surgical teams and two shock teams, the Hospital was ready to start receiving patients again on 12 August. The extra teams were then withdrawn and sent to assist other medical units at Rennes (liberated 4 August 1944 –ed) and Le Mans (liberated 8 August 1944 –ed) in Brittany.

Pfc Carl P. Kulinsky (service 17 September 1942 – 16 July 1945) with friends, while bivouacking in a field.

Because of the rapid advance of Patton’s forces the 39th became increasingly removed from the front, consequently admissions were low, personnel even had time to watch a movie after service hours. The Hospital did not report any admissions for 15 August. Instead, the C.O. received a message ordering him to send a reconnaissance team to scout out a new location near Arrou, some 120 miles east of Vitré. The Hospital now utilized the services of 40 German PWs for KP, work details, and preparation of meals. On 16 August, unit personnel packed everything. The 39th Evac then received the “go ahead” from Lt. Colonel Charles B. Odom (TUSA Chief Surgical Consultant, friend and personal physician of General G. S. Patton, Jr. –ed), to move to Arrou (Lt. Colonel Odom was wounded by an enemy sniper on 17 August, escaped death, and returned to duty three days after the incident). The Hospital moved to its new location on 18 August and set up next to a small lake which proved to be ideal for swimming. Some of its equipment did not reach Arrou until the next day in a second convoy. As the unit started admitting and treating its first patients, Patton’s troops continued their advance crossing the Seine and Yonne rivers, leaving the 39th once more far behind, meaning less patients. After the liberation of Paris (25 August 1944 –ed) , word was received that the 104th and 32d Evacuation Hospitals were moving closer to the frontlines and would be transferring all their patients to the 39th Evac. As a result, the Hospital admitted 224 patients that day. Things were slow, number of patients low, and as the unit was located in a non-combat zone, the Commander was instructed to find a new site for the Hospital. The new location became Nogent-sur-Seine (liberated 26 August 1944 –ed). On 28 August 1944, the 39th packed and started moving once more. Unfortunately, there were only 6 2 ½-ton cargo trucks available, which meant that several trips were required to move everything. All remaining patients were first transferred to the 614th Medical Clearing Company. By the end of the day installation was ready with the Hospital opening on 29 August with a limited staff (25 Officers and 60 EM). It should be noted that there was still German air activity over the region and Germans were still present in the woods near the camp. As the night wore on, 5 German soldiers were captured by some ambulance drivers. The remainder of the unit, including the Nurses, left Arrou only on 30 August. TUSA was meanwhile being held up for lack of gasoline, and as no dumps were around in the area, evacuation planes could not fly the wounded out to the United Kingdom. It was therefore decided to constitute a holding unit with the 39th Evacuation Hospital. Nevertheless, if the Hospital became swamped with patients, it was authorized to divert some of its patients to the 35th Evacuation Hospital.

Personnel in front of one of the Hospital’s ward tents.

After XII Corps captured a huge number of aviation gasoline (mostly at Châlons-sur-Marne, liberated 29 August 1944 –ed), air evacuation resumed, troops could continue their advance toward Commercy and the Meuse river, and the 39th was back in business and released from its holding duties. On 3 September, it admitted 131 patients coming from the 109th Evacuation Hospital; on 4 September, 96 patients were received; on 5 September, 50 patients came in. The next day, the Hospital received word to move again. It was to select a new location closer to the Moselle river and the front. On 7 September the advance party led by Major John J. Scanlon returned to inform that he had found a new area at a road intersection near Vertusey. While it rained profusely that day, the Hospital started packing and borrowed 12 trucks from the 101st Evacuation Hospital. Only a few Nurses and 8 EM stayed behind for the night should there be some emergencies. The remaining personnel left on 8 September in ambulances provided by the 580th Motor Ambulance Company. 9 September 1944 turned out to be ‘blood’ day for TUSA advancing against Nancy (liberated 15 September 1944 –ed), and that same day the 39th Evac admitted 138 patients. As the fighting developed, the men and women of the 39th battled to save the many wounded that came in; the Hospital was soon quite full and a backlog developed. Help was received from the 480th Motor Ambulance Company for evacuation of any soldiers whose condition allowed them to travel to other medical organizations further away from battle. On 11 September, 88 patients were brought in; on 14 September, 224 patients were admitted. The day was special, for Bing Crosby, being on an E.T.O. tour, chose to visit and perform at the 39th providing some relaxation to the happy few who could afford to watch the show. It was clear that the Hospital could not handle any more large numbers of patients, therefore, the unit only admitted 13 wounded in order to eliminate the surgical backlog which was thus significantly lowered. After the fall of Nancy (liberated 15 September 1944 –ed), days became hectic and the unit got overwhelmed with patients. Assistance was requested with some of the more serious cases being transferred to the 99th General Hospital.

When XV Corps captured Nancy, it took over control of a rundown hospital in town full of wounded German troops and malnourished Allied PWs. On 17 September, a motor convoy of twelve German ambulances, driven by enemy medical personnel, arrived at the 39th Evac. The Hospital was busy as it struggled to admit 181 patients and provide room among the wounded already admitted previously. Many of the arrivals were US airmen who had been shot down behind enemy lines, but the majority were Germans; 140 of them. The enemy wounded were extremely grateful as they had barely received proper treatment and many were suffering from life threatening infection. On 19 September the unit admitted another 146 patients; the next day 117 more came in. As it became apparent that surgery personnel became overworked, assistance was requested. Teams were provided from the 5th Auxiliary Surgical Group (attached to the Ninth United States Army, they would stay from 21 until 24 September –ed). Autumn rains, mud, and mire continued to plague the unit for the remainder of the month. On 26 September, the 39th processed its 4,000th patient. On 27 September 1944, Brigadier General Thomas D. Hurley, Surgeon TUSA, visited the Hospital. He informed the staff to seek for a permanent location west of Nancy, and Toul (it would become an important transfer point for cargo bound to Germany and to or from Verdun, Metz, Etain and Nancy –ed) got selected. Everyone started packing with the remaining 6 patients being turned over to another unit. It rained heavily but a large detachment from the unit managed to reach Toul in advance with the task to start cleaning and preparing several possible buildings that were to house the Hospital.

Liberation of Nancy. Armored elements of the 654th TD Battalion, attached to the 134th Infantry Regiment, 35th Infantry Division, enter the city. Picture taken 15 September 1944.

On 1 October, the 39th Evacuation Hospital transferred to Toul (where the 32d Medical Depot Company was already installed since 20 September –ed) in a long convoy of 2 ½-ton trucks and 10 ¾-ton ambulances provided by the 430th Motor Ambulance Company. After two days of extensive cleaning (the Germans had left a mess of the place after their departure), the unit was glad to be housed in permanent buildings, and opened on 3 October, admitting 21 patients. Due to the adverse weather, a number of cases were non-battle casualties. On 6 October, six surgical teams from the 4th Auxiliary Surgical Group were temporarily attached to the 39th. Medical units supporting Third Army’s drive to the Moselle river were spread out along a line running from Verdun to Nancy, with Evacuation Hospitals paired for alternate movement and Medical Depot Companies. To remove casualties necessitating longer care, air transportation was foreseen. Assuming that ComZ installations would fall behind during TUSA’s advance, the Third Army Surgeon organized his own rear holding unit. Toul became the most important holding center, consisting of the 94th Medical Gas Treatment Battalion, reinforced with an Ambulance Company, a Medical Collecting Company, a Field Hospital Platoon, and additional Evacuation Hospitals. The units evacuated over 9,700 patients using 6 different forward airstrips.

Service troops stationed in the vicinity of Toul, France. Toul was an important Air Holding site where a cluster of medical units was set up including a Medical Gas Treatment Battalion and two Field Hospitals.

At this time, the Hospital was currently operating with a staff of 73 Officers, 51 Nurses, and 786 Enlisted Men.

On 21 October, Colonel William S. Middleton, ETOUSA Chief Medical Consultant (-ed), visited the Hospital. He noticed that many patients had trench foot. The only possible cure was prevention, by keeping one’s feet dry, changing socks, massaging both feet, and removing shoes once a day, which was far from practical when in the field. On 22 October some Hospital members had a little time to visit the old WW1 battlefields at Verdun. Orders were received to close and pack for another move, closer to the German border. During the next few days, the C.O. of the 67th Medical Group was admitted at the 39th. After receiving appropriate medical care, he was evacuated by air. On 2 November a new location was selected in the vicinity of Pont-à-Mousson where suitable German barracks were available. On 5 November, Colonel Charles H. Beasley, ADSEC Surgeon (–ed) visited the hospital buildings in Toul. The next move was however cancelled because of Patton’s new strategic plans for the Third Army. In the end, it was decided to reopen the buildings in Toul. The heavy fighting around Metz produced so many casualties that the 39th had to request help from the 90th General Hospital, which provided two shock teams. Ambulances had to struggle through rivers and mud to reach the facility, and the already poor situation was exacerbated by the constant rise of the Moselle river making passage on the bridge at Pont-à-Mousson impossible. On 12 November, following orders, Major John J. Scanlon and Lieutenant Paul F. Ferreira, accompanied a group of EM to search for a new area for the Hospital. Once more the move did not go through and a phone call was received ordering the 39th to reopen its installations in Toul. On the same day, the unit admitted a total of 203 patients, of which 88 had trench foot. On 14 November, the Hospital closed again. The open field selected previously did not seem very suitable because of the bad weather, and TUSA Headquarters promised to help find a new site. On 15 November, following recommendations from TUSA’s Surgeon, Colonel Allen N. Bracher and a recon team traveled east of Toul to a town called Morhange. While on site, the C.O. visited the recently abandoned ”Adolf Hitler Kaserne”. As soon as the party from the 39th had left the place, the 58th Field Hospital moved into the area and started preparing barracks and buildings (which needed significant repairs) for several hospitals, including the 39th Evac. The town was still being continuously shelled by enemy artillery. Back in Toul, the unit packed all remaining hospital equipment and prepared the move for 19 November. However, during the evening, Colonel Bracher was informed that the selected “Adolf Hitler Kaserne” was to be used by another unit. Frustrated and quite angry, a new visit to Morhange was arranged in order to look for another suitable location. Finally the “Heinrich Himmler” barracks were chosen and although cleaning and repairs were necessary, an advance team of 3 Officers and 160 Enlisted Men traveled to Morhange and set up the equipment in some of the cleaner rooms while pitching additional tents adjacent to the hospital building. The move took place in limited convoys of a mere 8 vehicles and at fifteen minutes intervals; transportation was supplemented by the 94th Medical Gas Treatment Battalion. Repairs and cleaning took more than three days. On 23 November, personnel were abruptly woken at 0200 in the early morning by incoming German 280mm artillery shells raining on the city. Fortunately no shells hit the Hospital directly, although the ground shook and some parts of the brick walls were blasted into rubble. The unit admitted 98 patients of which many had been injured during the shelling. Also one of the sentries on duty was wounded and died notwithstanding all the medical care. The weather remained cold and rainy making life miserable, but even worse was the German barrage that continued. One day, a shell hit the mess tent, sending pots, pans, tableware and provisions everywhere and across the muddy ground. The supply room also received a hit causing a huge loss of medical supplies and other essential equipment. One of the NCO’s was injured by broken glass and suffered numerous lacerations; he was successfully treated, and later awarded the Purple Heart (the only member of the 39th to receive this honor).

Picture of Colonel Charles B. Odom, MC, Surgery Consultant to the Surgeon, Third United United States Army (Colonel Thomas D. Hurley).

The surgical backlog reached over 200 cases, hence the Hospital was closed for two days, except for emergencies. Not only American patients came in, also wounded Germans were admitted. On 29 November, 4 Officers and 68 Enlisted Men from the 92d Medical Gas Treatment Battalion were attached to the Hospital. Later a shock team provided by the 2d General Hospital was also temporarily attached. By 4 December all the extra personnel had returned to their respective units. To fill in for them, 4 Nurses from the 5th General Hospital and 1 American Red Cross worker came over to help with treatment. A small ceremony was held by Colonel Allen N. Bracher during which 6 Nurses were promoted to First Lieutenants (Theresa M. Baumgartner, Willa R. Hinkle, Mary C. Hohl, Phyllis A. Lindmeier, Mary E. Morefield, Bernice Tonjes). On 5 December the Hospital admitted 112 patients among which a French lady called Joséphine Provak. She was in labor and the Nurses helped her give birth to a small baby. On 8 December, the unit admitted 155 patients. Colonel Albert C. Lieber (Hq XII Corps) was one of them. He was visited by his boss, Major General Manton S. Eddy (CG > XII Corps). On 9 December, admissions were light which enabled 44 lucky Nurses to obtain 48-hour passes to go visit Paris. On 11 December, Brigadier General Ralph J. Canine (CofS XII Corps) was brought in with a leg injury. The weather was still sore and slowed down Patton’s advance. The weather was not only turning colder, snow began to cover the ground in some places. On 12 December, the 39th admitted 119 patients; on 13 December, 151 were received; on 14 December, another 104 came in, on 15 December, 122 more were brought in … and on 16 December 1944, the Germans launched their last great counteroffensive in the Belgian Ardennes.

Continental locations of the 39th Evacuation Hospital, European Theater of Operations

FRANCE

Bricquebec: 19 July 1944

Ste-Mère-Eglise: 21 July 1944 – 31 July 1944

St.-Sauveur Lendelin: 1 August 1944 – 6 August 1944

Vitré: 8 August 1944 – 15 August 1944

Arrou: 18 August 1944 – 28 August 1944

Nogent-sur-Seine: 29 August 1944 – 7 September 1944

Vertusey: 8 September 1944 – 29 September 1944

Toul: 3 October 1944 – 15 November 1944

Morhange: 23 November 1944 – 20 December 1944

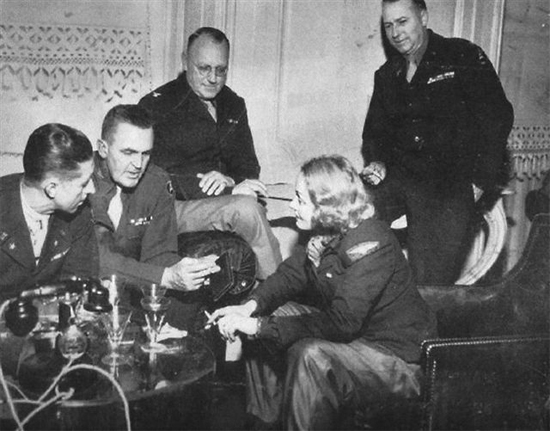

Marlene Dietrich (USO artist & performer) visting TUSA Headquarters at Nancy, France. Picture taken in November 1944, during the latter’s visit to one of the Officers’ Messes.

Belgium:

On 17 December, the Hospital only admitted 53 patients for there was little activity on Third Army’s southern lines. On 18 December, the situation in the northern part of the Bulge became increasingly dreadful and it appeared that the enemy breakthrough was greater than previously believed possible. Some American units had already been cut off or surrounded. All units were on full alert. On 19 December the unit admitted 107 patients with many of them coming from hospitals preparing to either move or retreat. On 20 December 1944, TUSA combat units started hitting the Germans, casualties grew fast, and more medical units were needed at the front. Among them was the 6th Convalescent Hospital which borrowed eight trucks from the 39th for its move. The Hospital was meanwhile looking for a new location closer to the frontlines, and before it closed, 61 more patients were admitted for immediate treatment. The reconnaissance team searched for usable buildings and a site in Esch, Luxembourg (where the 110th Evacuation Hospital was stationed), but returned unsuccessful. As the number of casualties grew constantly medical care was critical, moreover XII Corps began attacking the enemy and also required increased medical support. Around noon, 22 December, the team reached Headquarters of the 107th Evacuation Hospital (which recently moved away from Clervaux, retreated to Libin, moved to Carlsbourg, and finally fell back to Sedan –ed), near the Belgium-Luxembourg border. At first it was suggested to join forces with the 107th Evac, but this proved unadvisable by the lack of space to operate two hospitals efficiently. After several calls by the C.O., the Civil Affairs Officer of Virton (Belgium) suggested to set up in this town, located in the south of Belgium.

It was very cold, and it snowed, but the sun broke through the gray skies and for the first time, Allied aircraft were able to organize sorties against the Germans. After borrowing some trucks from another organization, the Hospital’s advance group set off across the Moselle river en route to Virton. As soon as the trucks arrived in town, the EM began unloading and setting up the Hospital at St. Joseph’s College (a girls’ Catholic School) which provided ample space for the entire unit. The 39th opened on 24 December. Midnight Mass was arranged in the school’s chapel, followed by Christmas carols. On 25 December, Christmas Day, the Hospital admitted 167 wounded. Personnel were fortunate to receive a hot meal and everyone was in excellent spirits despite being far away from home and caught in bitter winter weather. After the relief of Bastogne (26 December 1944 –ed), numerous wounded soldiers arrived at the 39th Evac; many had suffered severe burns and body trauma from the enemy artillery, not to mention cases of frostbite and trench foot. Most of the patients had injuries between five and seven days old. 148 Bastogne wounded came in on 27 December. Toward the evening, the remaining elements of the 39th which had remained at Morhange arrived at Virton. Along the way they were strafed by a German plane. Two drivers barely escaped injury as they swerved out of the path of speeding enemy bullets. On 28 December an additional 14 airborne casualties were admitted. On 30 December, the Hospital admitted 141 patients, among which their 10,000th patient! On 31 December, the weather was awful, with fog and heavy snow dominating the skies. Nevertheless, the 39th had a great New Year’s party.

Personnel of the 39th Evacuation Hospital on a visit to the “Siegfried Line” (Westwall) … a mass of dragon teeth, barbed wire, pillboxes, and minefields …

On 1 January 1945, 176 patients were admitted. As more patients came in, a slight surgical backlog occurred and in order to assist the unit’s litter bearers, 21 Enlisted personnel from the 437th Medical Collecting Company were temporarily attached. On 3 January another 109 patients were brought in. On 4 January 139 wounded were admitted. On 6 January, the 39th admitted 155 patients; the next day they numbered 109; on 9 January, 137 were admitted; on 10 January 183 patients came in. The Hospital was almost running out of room and it became necessary to evacuate patients who were healthy enough and stable to Station Hospitals in the rear. On 12 January, the Hospital admitted 86 patients and another 181 were brought in the next day. To help with transportation, 24 men from the 460th Motor Ambulance Company were attached for a few days. On 14 January, 108 patients were admitted; on 15 January, 60 were brought in; on 16 January, 87 were admitted; on 17 January, 133 were received … many trench foot cases were also received in the same period.

The Germans were slowly being pushed back, and as the front was crumbling further each day, Lt. Colonel A. N. Bracher was instructed to move his unit closer to the frontlines. TUSA Medical Headquarters suggested St. Hubert. A scouting party was sent to check the new location. A school building was available on the outskirts of town, it was large enough to house the wards and personnel. Having been used to quarter German troops, and suffering from shelling and some lack of proper maintenance, the building was in need of substantial repairs. There was no water and no electricity. An advance team arrived on site and started repair works with support of an Engineer unit. The task was complicated since 200 children had found refuge in the building and needed to be evacuated to safe areas in the vicinity. On 25 January, the Hospital at Virton was ready to transfer to St. Hubert. Notwithstanding heavy snow, the 39th moved to St. Hubert in trucks provided by other units where it arrived by nightfall the following day. Upon arrival they were rather disappointed for there was little water available and still no electricity throughout town. On 27 January, the men still at Virton, packed all the remaining equipment and set out for St. Hubert. Small generators were provided and a water tank truck was positioned near the school to provide water for patients and staff. Many incoming cases suffered from trench foot and exposure to cold and wet weather.

In response to Third Army’s progress, the Hospital was instructed to prepare for another move. A scouting party headed toward Troisvierges in Luxembourg, but returned to St. Hubert during the evening, having found no suitable location. Since the frontlines were moving away from St. Hubert, the 39th started treating more and more non-combat injuries. Meanwhile the unit was still looking for a new site. Major J. Scanlon visited Vianden, Luxembourg, and inspected a girl’s school and military barracks and determined the barracks would be suitable. The permission to relocate at the new site was however refused by TUSA Headquarters.

On 13 January 1945, Lt. Colonel A. N. Bracher was promoted to full Colonel.

39th EH personnel having a beer fest … time to celebrate, Germany is on the brink of total defeat …

Though the 39th Evac continued to treat wounded and injured soldiers on a regular basis, the Hospital’s major problem was that it was much too far from combat. On 15 February, the C.O. sent Major J. Scanlon to Prüm, Germany, but as the region was not entirely cleared of enemy troops, the location proved too dangerous. Third Army still required the 39th to select a position closer to the combat zone to support its units. Since there were fewer patients and lesser emergencies, some of the days were dedicated for arranging award and promotion ceremonies for the Hospital’s staff. After several scouting parties in the region, the reconnaissance team returned to Vianden, in Luxembourg, and discovered a sanatorium built on a grassy hill overlooking the town. It needed cleaning and repair but was large enough for operating the Hospital. After moving, the 39th received some help from Army Engineers who assisted with cleaning the premises, repairing the roof, and fixing the central heating system, and by the end of the day (this was 1 March 1945), the sanatorium building was ready.

Continental locations of the 39th Evacuation Hospital, European Theater of Operations

BELGIUM

Virton: 24 December 1944 – 25 January 1945

St. Hubert: 27 January 1945 – 26 February 1945

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg:

On 3 March, the Hospital moved to Vianden in trucks supplied by the 109th Evacuation Hospital. As there were not enough trucks it would take a few days to move all the equipment. Upon reaching the new location, many men became sickened; dead bodies covered the hill, in their hasty retreat, the enemy had left their dead to rot in the field and the stench in the area was awful. EM cleared the bodies from the hill and sent them to mass graves for burial. By 5 March all of the unit’s personnel and equipment had reached Vianden, and by midday, the Hospital was up and running, admitting its first patients. 1 Officer and 28 EM from the 634th Quartermaster Laundry Company arrived and cleaned the bloody bedding and surgical clothing. On 7 March, the Hospital admitted 98 patients. During the day search parties visited the woods around the hill and found more American and German bodies, it was tricky as there were quite a number of mines in the area. Some men got a chance to visit the Siegfried Line and discover the dragons’ teeth, since the fortification was a mere three miles from the Hospital’s site. On 8 March, a small surgical team pertaining to the 1st Auxiliary Surgical Group arrived and helped carry out a few scheduled operations with the unit’s surgeons.

Things continued to be quite slow for the remainder of March and a few Nurses were transferred to other Evacuation Hospitals, where extra help was needed. On 16 March, a number of German PWs came in. They had been evacuated from a Hospital across the German border. On 20 March, it became apparent that Third Army troops would soon be deep in Germany within the next weeks, and Colonel Bracher received a call ordering the 39th Evac to close at its present location. Suitable German barracks were located in Bad Kreuznach, Germany. Upon arrival, the advance party discovered that there was little damage to the buildings, they did however require extensive cleaning.

Continental locations of the 39th Evacuation Hospital, European Theater of Operations

GRAND DUCHY OF LUXEMBOURG

Vianden: 5 March 1945 – 21 March 1945

Germany:

The 39th Evacuation Hospital moved into Germany on 24 March 1945. The unit’s long convoy en route for Bad Kreuznach was now entering Germany, an enemy country, where “no fraternization” was the rule! Around noon the 39th reached the town and set up in the “Adolf Hitler Kaserne”. This was the first place the Hospital had ample room to hold all patients and personnel comfortably. As water was hard to come by, a water truck was parked in front of the barracks (daily consumption averaged 5,000 gallons). On site, the 39th welcomed a neighbor; the 121st Evacuation Hospital.

On 30 March, 4 Nurses from the 238th General Hospital were temporarily attached to the unit because their hospital had not yet opened. Major J. Scanlon and 10 Enlisted Men of his group received some furlough to the French Riviera in Southern France, it was a welcome break after having spent much of the past weeks risking death while scouting for new locations to set up the Hospital. On 1 April, General Patton’s forces were closing in on the city of Weimar and many of TUSA’s hospitals began to move forward again to catch up with the quick space of the combat units. On 3 April, Lt. General G. S. Patton, Jr. came to Bad Kreuznach, but he did not visit the 39th Evac. He went to another Hospital which had previously cared for his friend, Maj. General John L. Hines (CG > III Corps, pertaining to Third United States Army –ed). During his visit he noticed several patients with self-inflicted wounds which particularly upset the General. These types of wounds were becoming more prevalent as the war was drawing to a close. After closing operations, the 39th sent all such cases to the 110th Evacuation Hospital. The Hospital was now set for another move which was to take them to Hersfeld, not far from Weimar.

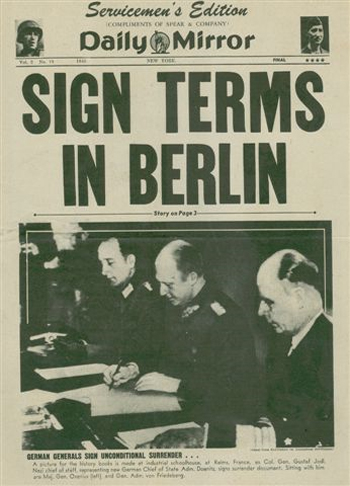

Servicemen’s edition of the “Daily Mirror”,Volume 2, No. 19, published in New York, U.S.A., announcing the Unconditional Surrender of Nazi Germany.

On 4 April, the unit rolled down the Autobahn in a long convoy toward Hersfeld. It started its move at 0600 aboard cargo and personnel trucks provided by the 34th and 12th Evacuation Hospitals. Upon reaching Hersfeld, tentage was installed at one of the freeway junctions. A large surgery was set up in one of the storage tents and antiaircraft artillery sat on each of the four corners of the new position. Everyone soon realized how much they missed the comfort of buildings and loathed being housed in tents. The Hospital was situated near a series of airstrips, making air evacuation easier. On 5 April, the unit was well established, just waiting for the Nurses to arrive from the previous location. On 6 April, the Officers realized that setting up tents so early in spring was not such a good idea. It rained almost all day and the ground turned muddy. Fortunately he Hospital was adjacent to the Autobahn so that ambulances could stop nearby and litter bearers could carry the wounded to the Hospital preventing the vehicles from getting stuck. On 9 April a German airplane flew over the Hospital and strafed the airstrip at Hersfeld. Several soldiers received bullet wounds and were quickly brought to the 39th for treatment, one of the patients however died of his injuries. TUSA Advance Headquarters “Lucky Forward”, meanwhile moved from Frankfurt to Hersfeld, with General Patton’s trailers installed directly next to the Hospital starting on 10 April. Many members of the 39th got a chance to see “Old Blood ‘n Guts” as he walked about the area with his staff. His appearance certainly inspired many to work harder.

During the morning of 11 April, German planes again attacked the area. The Hospital remained unscathed, but the 32d Evacuation Hospital was directly hit. Several rounds hit a young Lieutenant in the leg, which had to be amputated later in the day. The men and women in the 39th got lucky, as they were only ten miles down the road from the 32d Evac. On 13 April 1945, Lt. General G. S. Patton, Jr. came to the Hospital in search of Colonel Robert S. Allen (XO to Colonel Oscar W. Koch, ACofS G-2 Third US Army –ed) recently freed from captivity. The Germans had shot off his right arm just below the elbow. Upon his evacuation he had been brought to the 39th, carried into ward six, where the doctors tried to save his arm. In the end they had to amputate the mangled limb. Patton personally presented the Purple Heart to Colonel R. S. Allen for his injuries and took some limited time to tour the Hospital. He also presented Nurse Dagney Solberg with the Bronze Star Medal, for having organized triage for more than 700 of his wounded soldiers. More visitors came to visit the ‘special’ patient including Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar N. Bradley, and Otto P. Weyland.

While stationed at Hersfeld, all members of the Hospital received the opportunity to visit the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. What they witnessed would stick with them for many years to come. After its liberation (11 Aril 1945 –ed), both the 35th and the 120th Evacuation Hospitals were rapidly detached to the camp to administer the recently liberated sick and injured inmates.

On 14 April 1945, Third Army’s CG, George S. Patton, Jr. was promoted to full General.

On 20 April, Colonel A. N. Bracher received a telephone call ordering the Hospital closed. Immediately after the call, Major J. Scanlon was ordered to look for a new location closer to the Czechoslovak border. The rest of the men started packing. There was however a shortage of transportation means, as many of the Hospital’s trucks were already in use by the 109th Evacuation Hospital for its latest move. On 22 April, all patients were evacuated and the facility closed. However, the C.O. then received another call cancelling the planned move. Instead, Colonel A. N. Bracher was to call the XII Corps’ Surgeon’s Office for a new location. Despite bad weather conditions, the 39th left Hersfeld for Weiden, Germany on 23 April. The unit had to borrow fourteen trucks and a large caterpillar to pull the vehicles across the muddy field. Extra trucks and ambulances came from the 107th Evacuation Hospital to help with the transfer. By midnight of 24 April, both III and XX Corps had reached the Danube river.

On 24 April, the 39th reached Weiden, and after setup the Hospital admitted its first 8 patients. The town had seen the touch of war, many buildings had been destroyed, streets had been pulverized, some houses were still burning, and dead and burned bodies covered the ground. On 25 April, the unit admitted 124 patients, many of which were ex-American PWs. Most of them were malnourished and sick. Over the next few days, Third Army advanced further and the 39th continued to provide medical support to its fighting units. On 2 May, the C.O. received orders to close the Hospital; however, the unit was not to scout for a new location.

The war seemed to be coming to its end. On 4 May 1945, TUSA elements approached Linz, Austria, which fell on 5 May, and General Patton received instructions to move into Czechoslovakia, capture Pilsen, and advance toward Prague. On 5 May, Colonel Bracher was instructed to reopen the Hospital at Weiden. During the advance into enemy country, sizable bodies of German troops drove fast to surrender their forces to American units, before the Russians caught them in the rear.

Partial scene illustrating some of the ex-inmates of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, after the Camp’s liberation 11 April 1945, by troops of the 6th Armored Division, Third United States Army.

Number of Casualties admitted and treated in Third Unites States Army Hospitals

(1 August 1944 – 30 April 1945)

| US troops | 91,454 |

| British troops | 506 |

| French troops | 2,095 |

| US Navy & Marine Corps personnel | 265 |

| Royal Navy & French Navy personnel | 6 |

| French Forces of the Interior | 188 |

| Civilians | 2,635 |

| German military personnel | 16,989 |

American units received information on 7 May 1945 that Germany had surrendered unconditionally to the Allies earlier in the day. The news brought to a halt any offensive movement by Third United States Army troops. The war in Europe was over! The day was filled with cheers and celebration for the 39th Evacuation Hospital and for the first time since reaching the European mainland, the Hospital finally got to use its lights during the night. No more blackout.

Continental locations of the 39th Evacuation Hospital, European Theater of Operations

GERMANY

Bad Kreuznach: 25 March 1945 – 3 April 1945

Hersfeld: 6 April 1945 – 22 April 1945

Weiden: 24 April 1945 – 30 June 1945

Amberg: 5 July 1945 – 7 September 1945

Closing of the 39th Evacuation Hospital

Mission Accomplished:

13 May 1945 was an important day for all military personnel as SHAEF issued the ASR score system (Adjusted Service Rating), and reaching a minimum number of “points” became very important. Each member of the 39th Evac Hosp, whether an Officer, a Nurse, or an Enlisted Man, received a card in which to calculate his/her points (ASRC WD AGO Form No. 163 –ed). On 15 May, Colonel A. N. Bracher received orders to close the Hospital at Weiden. All attached personnel, except for the Laundry Platoon and the Ambulance Section, were relieved. It was a bitter-sweet parting for many people who had served alongside the men and women of the 39th. The next few months, the unit saw many of its personnel leave for duty elsewhere as well as for the Zone of Interior and home.

On 23 May 1945, the first group of people returned to the United States. Some Officers traveled to Paris to attend a series of educational courses for Officers. Other people were released and sent to Assembly and Staging Areas in France. A formal parade was held on 2 June with presentation of awards. The 39th Evac was rewarded with the Meritorious Service Plaque for its great job during the Battle of the Bulge. Some individual members received appropriate awards and medals, a few Nurses received promotions, while others were granted 7-day passes to the French Riviera and 1-day passes to Pilsen. On 22 June 1945, the 39th Evacuation Hospital received news that it would be transferred from a Category IV unit to a Category II hospital (within the frame of the Readjustment Regulations, RR for personnel, there were 4 categories of troops: Category I – troops to be retained in the same Command; Category II – troops to be transferred from one Theater to another; Category III – troops surplus in a Theater and to be reorganized and reclassified as Category I or Category II; Category IV – troops to be disbanded –ed).

On 23 June, Major J. Scanlon was instructed to find a new location for the Hospital in the vicinity of Amberg. While on site, the reconnaissance team found a German Lazarett which appeared large enough and contained a lot of left-behind medical equipment. Major Scanlon informed the C.O. and the location was approved. On 25 June, Major Harry Adams received orders to proceed to the Dachau Concentration Camp, where he assisted with typhus control. He would spend a month on site, only returning on 25 July. Captain Herbert Gershberg (Chief of Laboratory & Pharmacy) went on DS with the 6th Convalescent Hospital to inspect the troops for syphilis in the Nuremberg area. On 28 June, the 39th Evac received additional campaign credits for its action in the Ardennes and Central Europe. The next day, Colonel A. N. Bracher awarded Chaplain George J. DeWitt, Nurse Gladys C. Stinson and Nurse Rose P. Kelly the Bronze Star Medal for valorous service with the Hospital. While the C.O. inspected the new location in Amberg, other Officers were sent to attend classes and training lectures in Paris, France, and Liège, Belgium. In July, some Officers returned home within the frame of the ‘Green Project’ (the program involved the assignement of additional transport planes to the A.T.C. for transatlantic service, which continued until 10 September 1945, and transported about 166,000 troops from the E.T.O, and the M.T.O. to the ZI; the “White Project” involved transportation of Army Air Forces crews and such other personnel that could be accommodated in bombers that returned from Europe to the States, reaching a total number of 85,000 men and women –ed) and more members of the 39th were awarded the Bronze Star Medal.

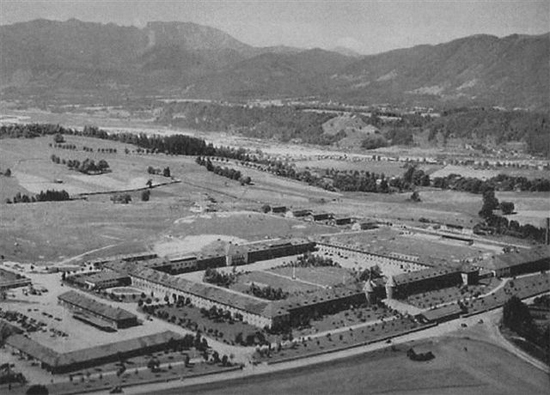

Bad Tölz, Germany. Forward Headquarters (“Lucky Forward”) of Third United States Army. This was a former SS-Junkerschule taken over by the US Army in 1945. Picture taken in June 1945.

On 3 July, 25 EM and 1 Officer arrived at Amberg to prepare the Lazarett for a permanent hospital setup. Several German civilians and military doctors were conscripted into service with the 39th Evac. The German Hospital had excellent equipment including X-ray machines. There was a separate laundry room; Nurses’ quarters; elevators; ice boxes; bathing and latrine facilities; and even a swimming pool. The kitchen was equipped with an ice cream machine.

Mid July 1945, it became apparent that quite a number of personnel had very few ASR points. Colonel Bracher contacted Lt. Colonel William E. Proffitt, Sr., Executive Officer of the 128th Evacuation Hospital and organized an exchange of Enlisted Men. The 39th transferred 47 low-point EM in exchange for 49 high-point personnel. As work in Amberg was light, EM built a tennis court and organized a couple of baseball teams. Others went on hunting and fishing trips. As part of an earlier arrangement, 45 more low-point Enlisted Men transferred to the 128th Evac in exchange for 49 high-point men. A number of Officers and NCOs returned to the States. More Officers were transferred out of the 39th and joined the 130th Evacuation and the 116th General Hospital. There was a continuous flow of personnel leaving the Hospital. On 4 August, one of its backbone members also left, Chaplain G. DeWitt transferred to the 610th Medical Clearing Station, and was soon replaced by Chaplain Robert Kieffer. Some people who had been on DS with other medical units returned to the Hospital, new elements joined to fill in some ranks, while small units were temporarily attached to the unit. On 25 August, Major J. Scanlon, the man responsible for scouting many new locations for the 39th, left for the 16th Reinforcement Depot, and later for home. The same month, the unit lost another 34 Enlisted personnel. As the Hospital complement lost more and more people, the future looked grim, and the organization was slowly falling apart. After returning from a 72-hour leave in Paris, the C.O. was informed that the Hospital had ended its service time in Europe and would be heading back to the United States. With the end of the war in the Pacific and the surrender of Japan (2 September 1945 –ed), there was no reason to keep the unit overseas, i.e. in Europe. All remaining patients were transferred to the 45th Field Hospital and on 7 September 1945, the 39th Evacuation Hospital closed its doors to all (except extreme emergency cases). Some of the Officers (Doctors and Nurses) were sent home and replaced by personnel from other hospitals in Germany. On 14 September, the EM prepared all basic and auxiliary equipment for shipment to the ZI. The remaining low-point unit members transferred to the 51st Field Hospital.

On 15 September 1945, the 39th Evac set out for home. It left Amberg at 0830 and made a short stop at Mourmelon, France, to pick up all remaining members of the 32d Evacuation Hospital. From Reims, the convoy traveled toward the French coast, where it was to wait for transportation. Upon arrival on 26 September, all Medical Officers transferred to the 19th Reinforcement Depot for air transport to the States, while the Enlisted Men had to wait for a ship that would take them across the Atlantic to the Zone of Interior.

On 26 September, Colonel Allen N. Bracher was relieved of duty as C.O. of the 39th Evac Hosp. He was subsequently assigned to Headquarters TUSA and left, heading for Munich, Germany. Replacing him was Lt. Colonel Arthur A. Brown, who was put in command for the last leg of the 39th’s history… Orders were received to board ship on 1 October, but logistics interfered and the move was cancelled. All remaining Nurses now transferred to the 166th General Hospital which was ready to ship out of Le Havre. Finally, on 15 October 1945, the 39th Evacuation Hospital moved to Mourmelon, thence to the Reims Assembly Area, where it was temporarily housed for another three weeks in one of the city camps, “Camp Philadelphia” (frequent passes for Reims and Paris were distributed to ease tensions and pass time). The unit was alerted on 24 October, and moved to Calais where it arrived on 27 October. On 1 November 1945, the 39th Evac boarded the “USAT Henry Gibbons” and arrived in Boston harbor on 13 November. With Lt. Colonel A. Brown still in command, all remaining personnel traveled to Cp. Myles Standish (Staging Area –ed). On 14 November, all unit members after having been processed received their separation papers and moved across the country to the various local Separation Centers for discharge and return home. The 39th Evacuation Hospital was officially inactivated by General Orders No. 112, dated 14 November 1945. It had successfully accomplished its combat mission.

Picture of Private First Class Carl P. Kulinsky taken in 1945, after having been Honorably Discharged from the United States Armed Forces.

Unit Personnel Roster: (incomplete)

| Clint E. Adams | Harry Adams (Maj, MC) |

| Monica Ames | Paul Anderson |

| Dotty Ayers | Burlah Barkley (2d Lt, MAC) |

| Theresa M. Baumgartner (1st Lt, ANC) | Ralph Benson |

| Sam Biondiollie | Alice E. Bowers (2d Lt, ANC) |

| Allen N. Bracher (Col, MC) | George Breslin |

| Arthur A. Brown (Lt Col, MC) | Howard F. Bultman |

| Mary S. Clarke | Fred Conti |

| Marilyn G. Cook (1st Lt, ANC) | Gene Dent |

| George J. DeWitt (Chaplain, ChC) | Pat Donofrio |

| Erma L. Davis | Isabelle Dick |

| William Downing | Hazel Dukes (2d Lt, ANC, N-764441) |

| Bernard Elmore | Sylvia Faruzzi |

| Tom Ferrater | Arthur Fladhammer |

| William Foster | Robert Gardner |

| Herbert Gershberg (Capt, MC) | James Ghiardi |

| M. Gibbons | Alice Gitterson |

| Wilbert Gohring | Mildred Gotts |

| Eddie L. Griffin (1st Lt, ANC, N-726750) | Lewis Hammon |

| Jeffrey Hanson | Jeff Hausen |

| Shirley W. Hayden | Stan Helberg |

| Vance C. Henry | Walter Hervi |

| Richard Hewitt | Willa R. Hinkle (1st Lt, ANC) |

| Mary C. Hohl (1st Lt, ANC) | Connie Hood |

| Robert Jacus | Annie L. Jennings (1st Lt, ANC, N-763368) |

| Eddie Jonas | Marie J. Joenneke (1st Lt, ANC, N-763070) |

| Byrle Johnson | Ruth B. Johnson (1st Lt, ANC, N-727739) |

| Tom Judge | Anne G. Kagel |

| Charles Kaman | Rose P. Kelly (1st Lt, ANC) |

| John Kennedy | Robert Kieffer (Chaplain, ChC) |

| Garnet Kimberlin | Clarence Knecht |

| Rex Koener | Frank Kojick |

| Hilda Kope | Albert K. Kruger |

| Walter Kubic | Carl P. Kulinsky (Pfc) |

| Roy W. Kyllander (Tec 5, 37305495) | Ruth Lamoureux |

| Frank LaPosa | Eddie Leverty |

| Alan Lewis | Phyllis A. Lindmeier (1st Lt, ANC) |

| Angela Loiacoia | Ed Mancene |

Major John J. Scanlon (30 May 1910 – 4 November 2001), Executive Officer, 39th Evacuation Hospital (Courtesy Todd Braun).

| Paul Marrow | Dorothy Maxson (Chief Nurse, ANC) |

| Laura McConnell | Robert M. McKinnis |

| Elmer Miller | Mary E. Morefield (1st Lt, ANC) |

| Mary Murphy | Lloyd Nicholson |

| Harry Nightingale | Elizabeth O’Reilly (1st Lt, ANC, N-727943) |

| James R. Ognibene | Deloy A. Palmer |

| Robert Parent | Genaro Porta Della |

| Isabelle Preston | Pete Procci |

| Bernard L. Rabold (Maj, MC) | Norman Rasmussen |

| Alfred Richlan | Catherine Robinson |

| David Robinson | Mona A. Ruark |

| Frank E. Rubovits | Norman R. Ruschill |

| Clarence Sandro | John J. Scanlon (Major, MC) |

| Rene Schmidt | Arthur Scott |

| Armand Sevasta | Winton E. Simpson (1st Lt, ANC, N-763819) |

| Roy Slusher | James Sneberger |

| Dagny Solberg | Mildred Sone |

| Gladys C. Stinson (1st Lt, ANC) | Theresa Sullivan |

| Lois M. Telmes (1st Lt, ANC, N-727005) | Bernice Tonjes (1st Lt, ANC) |

| Mary Vaughn | Bert Vaszily |

| Paul Vehle | James Vincent |

| Lloyd Walters | Mert Warbritten |

| Alta M. White (1st Lt, ANC, N-727186) | Al Wolfson |

| Tietz Woodruff | Lester Wygant |

The MRC Staff are particularly indebted to Steve Kyllander, son of Tec 5 Roy W. Kyllander (ASN: 37305495) who generously provided us with a book covering the WW2 history of the 39th Evac Hosp, and Jeremy C. Schwendiman, author of the book “Saving Lives, Saving Honor”, grandson of Pfc Carl P. Kulinsky, who kindly allowed them to use several paragraphs of the book and many period photographs from their private collections. A partial personnel roster was furthermore received from Pat Tumminello. Without their generous help, they would not have been able to edit the above document.