Veteran’s Testimony – Walter S. Kucharski 45th Evacuation Hospital

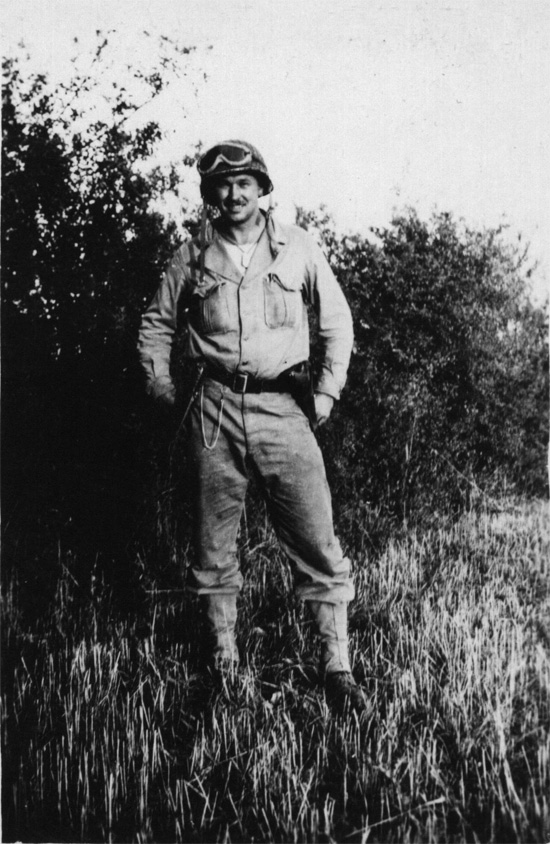

Photo of Private Walter S. Kucharski, ASN 32392630, taken while stationed at La Cambe with the 45th Evacuation Hospital, France, June 1944.

Introduction:

Walter was born Waclaw Kucharski on July 31, 1920 in Bayonne, Hudson County, New Jersey. His parents, Antoni Kucharski and Kataryna Oberwanowicz immigrated to America in the early 1900s from Poland and settled in Bayonne, New Jersey where they met and married circa 1914. Antoni, a strongly built man, held several laborer positions for the huge Standard Oil Company based in Bayonne. Walter was the fourth of nine children born from this marriage. As he got older, he developed exceptional athletic ability. In Bayonne during the 1930s, softball was a main pastime and Walter excelled at it. He starred on several fast pitch softball teams where his primary position was pitching and where he was known for a “big bat”. There are many box scores from that era that relate how Walter S. Kucharski pitched the win and got a big hit.

Since he was five years younger than his brother Billy, ”Big Pancho”, Walter was nicknamed ”Little Pancho”. Walter played on many winning teams and pitched on an all-star team representing Bayonne at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. He also boxed and featured in several matches prior to the war.

He would later recall how these days were not all cheerful. In his teen years, there were nine children to support in the family. One story, which he remembered fondly, was the one about playing after school. When school was dismissed, Walter had the choice of playing with his friends or going home for dinner. Due to the size of his family, the dilemma was, that if he chose to play with his friends, there was a chance that there would not be any dinner left for him when he got home. He also remembered collecting coal that fell off railroad cars rolling through Bayonne and picking up copper wire to sell to scrap dealers. This was depression era America when times were tough enough for one person, let alone for a family of eleven.

Sometime after 1930, the Kucharski family moved to a predominantly Polish section of the city. Dropping out of high school in 1938, he helped support his family with jobs such as turret lathe operator with the Singer Sewing Company and cable reel assembler with the General Cable Company. Then, tragedy struck twice. In 1940, Walter’s oldest sister, Natalia died in a senseless shooting at a neighborhood tavern. In 1941, his mother Kataryna died, leaving Father Antoni Kucharski to care for the eight remaining children. This was the situation on that late day in June of 1942 when Walter received the news that Uncle Sam wanted him.

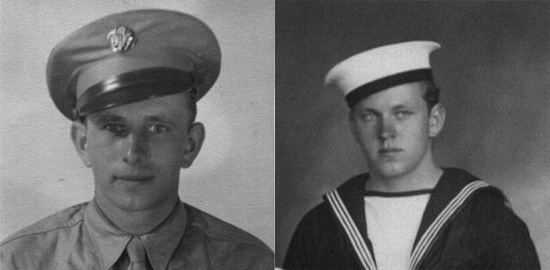

(Two of Walter’s younger brothers also enlisted in military service. Benjamin joined the Army and Anthony Jr., the Navy – Benjamin J. Kucharski, born August 4, 1922 joined the Army 17 April 1943, and received the Purple Heart for wounds suffered in battle, he died March 16, 1999 – Anthony Kucharski, Jr. born January 7, 1924 joined the Navy in July 1943, and passed away December 29, 1989 – both brothers are buried in Holy Cross Cemetery, North Arlington, New Jersey).

Left > Photo of Benjamin J. Kucharski (4 Aug 1922 > 16 Mar 1999) who joined the Army in 1943.

Right > Photo of Anthony Kucharski, Jr. (7 Jan 1924 > 29 Dec 1998) who joined the Navy in 1943.

Induction and Training:

It was an early summer day during June 1942 in Bayonne, Hudson County, New Jersey. The postman went from house to house on West 19th Street, delivering mail to the Polish blue-collar residents of that section of the city. Only 7 months after the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a war that seemed a world away, would knock on one particular door that very day.

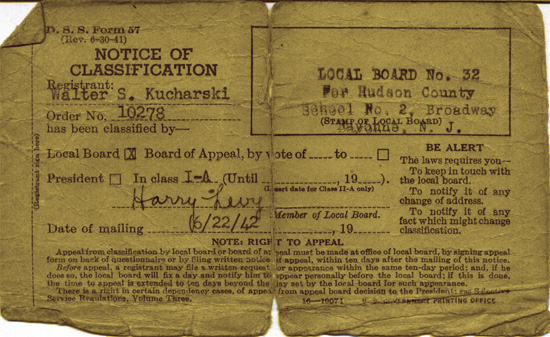

Toward evening, a strapping 21-year old walked up the wooden stairs of the house he shared with his dad and seven siblings (Walter Stanley Kucharski was over 6 foot tall and weighed almost 200 pounds). His father probably met him at the door and handed him the postcard that millions of American men received during the early months of the war, a Notice of Classification, DSS Form 57. Local Board #32 for Hudson County classified Walter as I-A: available for Military Service (after having been officially registered for Selective Service, as per the July 1, 1940 Selective Training & Service Act). Class I signified: available for service, while A designated: fit for general military service.

Notice of Classification dated 22 June 1942, delivered to Walter J. Kucharski, classifying him as available for Military Service (ref. I-A).

On July 15, 1942, Walter S. Kucharski was inducted into the United States Army in Newark, New Jersey. He formally entered military service on July 29, 1942 and was assigned Army Serial Number 32392630 (draftee classification).

Walter was sent to Fort Dix (Training & Pre-Staging Center –ed), Wrightstown, New Jersey for processing into the United States Army. The majority of the soldiers at the post were from the New York, New Jersey and Delaware area, Second Service Command, under First United States Army jurisdiction.

After little more than a week, he boarded a steam train to an unknown location. The trip took three days and was interrupted only by stops to eat meals from kitchens that were set up in boxcars. Finally, the train arrived in Augusta, Georgia. Basic training was to begin ten miles outside of the city of Augusta, at a military post named Camp Gordon (Division Camp –ed), Augusta, Georgia. The barracks were simple wooden buildings surrounding a training field. At this early period, Walter learned that the name of the unit he was to be assigned to would be the 45th Evacuation Hospital, Semi-Mobile (such units were the predecessors of those popularized by the M*A*S*H* television show illustrating military hospitals during the War in Korea). For the next six weeks, each day began early and consisted of a hike and drills in various military formations. Walter, always the gregarious one, became friends with several of the Officers in the unit. He became the driver for Major Robert J. Miller, an Officer with the Dental Corps. Walter would refer to him as a “regular guy”. He also became acquainted with the unit Chaplain, Father George W. Zinz, Jr.. After the basic training concluded, the men in the unit were assigned the various jobs they would perform for the duration of their service. In November 1942, Walter graduated from a course in “Second Echelon Maintenance and Repair”, and would also assist with various orderly duties (Walter took a 6-week course at the Mechanic’s School, Camp Gordon, Ga. in vehicle body and engine maintenance, he would later drive the CO’s staff car and 2 ½-ton trucks carrying personnel and supplies –ed).

After completing this course, he received a furlough and returned to Bayonne to marry his fiancée, Helen Sophie Nowicki. Helen, born February 18, 1922, also lived on 19th Street and was of Polish ancestry. They were married on November 14, 1942 at Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Church, Bayonne. At least once after their marriage, Helen traveled to Augusta to visit her husband. She stayed at a house in town that they named the Cozy-Inn. Each night during her stay, Walter would visit her after off-duty hours. They always remembered their time together at this house fondly.

Private W. J. Kucharski driving one of the unit’s jeeps (1/4-ton). The vehicle bumper markings read Second United States Army, 45th Evacuation Hospital, 3rd vehicle.

At this time, some of the people of Augusta still remembered the Civil War and some had resentment for “Yankees”. Walter would say about the townspeople; “They were still fighting the Civil War”. One night when Walter and Helen were walking in Augusta, two southern soldiers approached them. Unaware of Walter’s boxing experience, they made an unfriendly remark to Helen. Walter proceeded to flatten both soldiers and then the Military Police arrived on the scene. Walter thought he was in trouble, but when the MPs evaluated the situation, they decided Walter was justified and allowed him and Helen to go on their way. Walter was always particularly proud of this story.

By early 1943, the 45th Evacuation Hospital, still located at Camp Gordon, Georgia, became an operating unit. It was a self-sustained semi-mobile unit that could pack up all their equipment within 6 hours, travel 50 miles and then set up and be ready to receive patients within 24 hours. The organization consisted of:

Headquarters

Administrative Service —— Professional Service

Registrar & Detachment of Patients —— Medical Service

Medical Detachment & Personnel Section —— Surgical Service

Receiving Section —— Laboratory Service

Evacuation Section —— X-Ray Service

Mess Section —— Dental Service

Supply & Utilities Section —— Nursing Section

Wedding photo of Private Walter J. Kucharski and Miss Helen S. Nowicki, Bayonne, New Jersey, 14 November 1942.

It was equipped to handle any medical situation from a cut finger to extreme war wounds. A certain configuration was created for the entire hospital setup. The camp generally consisted of 30 large ward tents that contained receiving, triage areas, pre-operative wards, shock wards, bath tent, x-ray room, sterilizing room, dressing and dental tent, operating rooms, pharmacy and laboratory, and various other staging areas for administration, messing, and other services. The operating rooms were often lined with muslin or white sheets inside the larger tents in order to better reflect lighting. Moreover these rooms were 15 to 20 degrees cooler, making operating conditions beneficial to the patients. Five generators provided enough power to satisfy all the hospital’s electricity needs. The unit’s authorized strength (ref T/O 8-232, 750-bed Evac Hospdated 15 June 1941 indicated 47 Officers, 52 Nurses, and 318 Enlisted Men, while T/O 8-580, 750-bed Evac Hosp dated 23 April 1943 consisted of 47 Officers (including 1 Chaplain and 1 Dental Officer), 1 Warrant Officer, 53 Nurses, and 308 Enlisted Men. The original 750-bed Evacuation Hospital would later be reorganized as a Semimobile 400-bed Hospital unit under T/O 8-581 dated 25 March 1944 authorizing an aggregate personnel strength of 38 Officers, 1 Warrant Officer, 40 Nurses, and 217 Enlisted Men (with a possible expansion to 700 beds –ed).

Walter J. Kucharski, on work detail, anyone need a broom ? Photo taken while stationed at Camp Gordon, Georgia, 1942.

Maneuvers:

In April 1943, the unit learned that they would be participating in maneuvers in Tennessee. After several weeks of preparation, the unit loaded their gear onto trucks and drove to Shelbyville, Tennessee, the stage for the maneuvers. During this exercise, the unit provided medical support for the ”Blue Army”. A humorous event occurred during the training exercise that made nationwide newspapers. In the military, it was customary to have a Post Exchange, a government-owned store operated for the convenience of military personnel. During these maneuvers, the ”Red Army” captured the soldier who had the keys to the 45th EH PX. According to the rules of the maneuvers, prisoners were to be held for 24 hours. Before it was realized that the soldier with the keys had been captured, scouting parties were sent out to try to find the man. The consequence of his capture was that members of the 45th Evac Hosp couldn’t purchase any cold drinks, cigarettes or snacks during those 24 hours and it caused a minor inconvenience for the soldiers. The maneuvers lasted until October 1943. It was here that Walter learned that the unit was to become attached to the First United States Army.

Walter J. Kucharski with Chaplain George W. Zinz, Jr., while stationed at Camp Gordon, Georgia.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

At the beginning of November 1943, the unit reported to Camp Kilmer (Staging Area for the New York Port of Embarkation –ed), Stelton, in New Jersey for embarkation to England. On November 16, 1943, the organization boarded a ferry at Camp Kilmer and sailed to Pier 86 in New York Harbor enroute to the RMS “Aquitania”. This grand ocean liner, converted to a troop transport, was the sister ship of the RMS “Lusitania”, whose sinking by a German U-Boat precipitated the entry of the United States into World War I. Launched in 1913, RMS “Aquitania” served during World War I as a troop ship in the 1915 Gallipoli campaign, and the following year served time as a hospital ship. Idle for most of 1917, she began serving as a transport for American Forces in 1918. Her final assignment in World War I being repatriation of Canadian troops. The 45th Evac Hosp left New York Harbor on this historic ship November 17, 1943.

The RMS “Aquitania” was manned by the British Navy and policed by United States Army personnel. Most of the troops slept in hammocks and exercised in shifts. Travel on the ship was limited because it was so crowded. Meals were served twice a day, being breakfast and supper. A usual breakfast was oatmeal and tea while for dinner liver, tea and a biscuit were available. The trip across the Atlantic was basically uneventful with not much for a soldier to do. Besides emergency drills, and some KP details, the principal activity was gambling. As Bob Hope once said, ―”An army barracks is two thousand cots separated by individual crap games.”

Private Walter J. Kucharski, at the unit’s motorpool. Photo taken during the Tennessee Maneuvers in spring of 1943.

A British member of the gun crew of the “Aquitania” kept a journal of this crossing:

*17 November 1943, Wednesday – Left New York at 10:00 a.m. Cold as hell.

*18 November 1943, Thursday – Cold.

*19 November 1943, Friday – Cold as hell, headed toward Scotland.

*20 November 1943, Saturday – Getting warmer, sea a little rough, rain.

*21 November 1943, Sunday – Warm in gulf stream. Cleaned gun. Airplane school.

*22 November 1943, Monday – Sea little rough. Convoy attacked by 6 German planes, 100 miles from us.

*23 November 1943, Tuesday – Sea high. Biggest rolling sea I ever saw.

*24 November 1943, Wednesday – Got in Scotland at 6:30 a.m.. Cold as hell. Tore gun down.

On November 24, 1943, RMS “Aquitania” arrived in Greenock, Scotland. Situated on the south bank of the River Clyde as it becomes the Firth of Clyde, Greenock was known for its shipbuilding industry. As the 45th EH disembarked from the ship, they were given a handout picturing Winston S. Churchill flashing his famous “V-for-Victory” hand gesture and welcoming the Yanks.

The 45th Evacuation Hospital staff and personnel immediately boarded a train for an unknown location. During the trip, a stop was made to pick up food. Orders were given not to open the dinner package until the train was again underway. The hardships the British had faced were evident in the meal they provided. It was supposed to be a hot dog, but actually was cornmeal pressed into the shape of a hot dog.

On the following day, November 25, 1943, they arrived at their destination, Wotton-under-Edge in Gloucestershire, England. This was to become the unit’s home for the next seven months. Men from the unit were billeted in vacant homes, some of which did neither have modern plumbing nor heating conveniences. The townspeople treated the Americans well, frequently inviting them for tea and crumpets at their homes and to parties at the Town Hall on weekends.

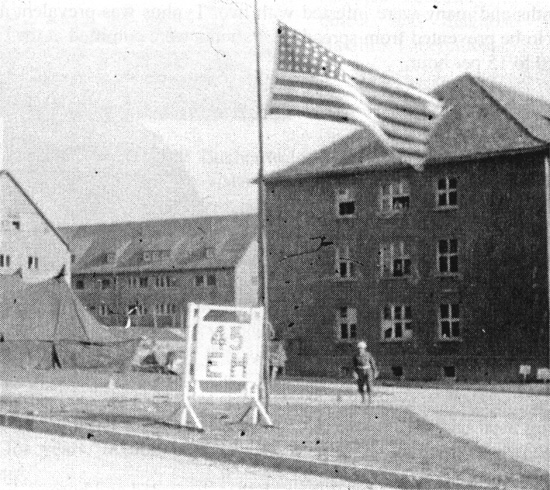

General view of the 45th Evacuation Hospital tented camp at La Cambe, France. The organization was stationed there from 16 June 1944 until 24 July 1944.

During this time, Walter continued his boxing. He eventually became the ETO (European Theater of Operations) champion and went on to have a bout with the United Kingdom champ. Not many details survive about the fight. It was held in London and many of the 45th’s men traveled by truck to see it. The fight went the distance, but Walter lost by a TKO (Technical Knock-Out). Walter later recalled that the British soldier who beat him was killed later during the war.

To show their appreciation to the townspeople of Wotton-under-Edge for their hospitality, the 45th EH staged a musical revue titled ”Buckle Down Buck Private”. It had 13 scenes and was directed by a soldier from the 45th who formally worked in burlesque. Walter had several parts in this production. He played ”Blackie” in Scene VIII and concluded the show as a voice in the girl chorus. He recalled that it was hilarious to see grown men dancing and singing while dressed in women’s clothing.

During this long stay in England, it wasn’t unusual for passes to be obtained so that the men could relax visiting various parts of England. While dining out, vegetables were plentiful, but meat was in short supply and rationed, further evidence of the many hardships England was experiencing. While the United States was a relative newcomer to the European war, Great Britain had been at war with Germany since September 10, 1939. They had suffered through the agony of Dunkirk, the Blitz of London, and the glory of the Battle of Britain. If the United States soldier was ever a welcome ally to the English, that time was now.

45th Evacuation Hospital enlisted personnel chowline. Photo taken while stationed at la Cambe, France, June-July 1944.

Omaha Beach, France:

On the morning of June 6, 1944, the soldiers of the 45th Evacuation Hospital awoke to the sound of aircraft making their way over the English Channel. The unit was put on a 24-hour alert, and they loaded their vehicles and awaited their marching orders. At 7:00 a.m. June 13, the unit left Wotton-under-Edge to the cheering of crowds of townspeople. They arrived at the Hursley marshalling area near Southampton later that day. There the soldiers were given a circular from General Dwight D. Eisenhower explaining the purpose of the invasion and wishing them good luck. Two days later on June 15, 1944, the 45th traveled to Southampton and boarded HMS “Gleanearn” for the trip across the English Channel.

We can now only imagine in awe the view that Walter and his comrades observed when crossing the English Channel that day. It was D+10 and the channel was full of countless ships visible in all directions. At around 2:00 p.m. on June 16, 1944, the ship anchored off Omaha Beach on the coast of Normandy. The soldiers, loaded with full field packs, climbed over the rails of the ship into LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry). The beach was littered with metal anti-tank obstacles, barbed wire, debris of war, and bomb craters. After landing on the beach, the unit assembled and was ordered to dig foxholes in the sandy beach. Several hours later, trucks arrived and drove the unit 8 to 10 miles along the beach to a town called La Cambe.

The situation the Allies found themselves in at D+10 was not encouraging and it was feared that the Germans would force a stalemate in Normandy. Much of this concern was caused by British General Bernard L. Montgomery’s inability to capture the key city of Caen. If this key city fell to the Allies, there would be nothing but open fields to cross to get to Paris, the French capital. Therefore, the bulk of the German panzer units were fighting fiercely north of Caen. However, by July 1944, with the strength of the First United States Army close to 500,000 troops and the amount of supplies and equipment continually pouring onto the beaches, it was just a matter of time before the Allies would break out of the Normandy beachheads (by July 24, 1944, total Allied strength in Normandy reached 1,332,000 men –ed).

Enlisted men in front of their pup tents. Photo taken at Airel, France, where the 45th Evacuatio Hospital was stationed from 25 July 1944 to 8 August 1944.

The 45th Evacuation Hospital was ordered to establish camp in a field surrounded by hedgerows at La Cambe. Hedgerows dated back to the Roman era and were designed to mark boundaries and keep cattle contained. They were typically two to three feet in width and as much as five feet deep with thick brush on either side. Some even resembled leafy tunnels and were situated at irregular angles through the countryside. The hedgerow country of northwestern France, called the “bocage” presented a trying challenge to the US Army in 1944. Its military features were obvious. The hedgerows divided the countryside into tiny compartments. They provided excellent cover and concealment to the defender and a formidable obstacle to the attacker. Numerous adjoining fields could be organized to form a natural defensive position echeloned in depth. The thick vegetation provided excellent camouflage properties and limited the deployment of units. The hedgerows further restricted observation, making the effective use of heavy-caliber weapons almost impossible and hampering the adjustment of artillery fire. During the Normandy invasion, the First United States Army faced a stubborn German Army defending from an extensive network of small fields surrounded by living banks of hedgerows. German forces fighting from ready-made defensive positions were, at first, able to curb most of the American advances and make the attempts very costly. Busting through the difficult bocage country required tactical as well as organizational ingenuity. Combined arms operations was the answer to fighting in difficult terrain. The adoption of new tactics combined with technical innovations and good small-unit leadership enabled American forces to defeat a well-prepared and skillful enemy. In the hedgerow country, components of the combined arms team, infantry – armor – artillery, were the only way to beat the enemy. The resulting successes were costly but effective. The early fighting in Normandy was costly to the Allies because of these natural obstacles. Often, it was like fighting in a maze. Germans would shoot down soldiers moving through the hedgerows by setting up machine gun positions with the space in the rows in their range of fire. The Allies tried to fight through these hedgerows with dozer tanks and special vehicles. The latter were brought in and consisted of tanks equipped with a “Culin” device welded on to the front of armored vehicles to help break through the earthen embankments (2d Armored Division, Sergeant Curtis G. Culin took the idea to heart and designed and supervised the construction of a hedgerow cutting device made from scrap iron retrieved from a German roadblock obstacle –ed).

As night approached, tents were set up close to the base of the hedgerows so that they could be used for some protection. All through the night, anti-aircraft and other types of gunfire resounded. This occurred every night for weeks afterwards. The Luftwaffe also sent planes to bomb the Allied positions at night. The Americans called these night-time visits, ”Bed Check Charlie”. The planes would drop their bombs at random and cause little damage but fray the nerves of the troops on the ground. The enemy nicknamed the Normandy beachhead, “Golden City”, because of the fiery dome caused by gunfire during the night. As the weeks went by and the beachhead enlarged, less German fire was heard at night. Allied P-47 Thunderbolts, (“Jabos” or Fighter-Bombers as the enemy called them –ed), equipped with eight .50 cal. MGs and armed with ten 5-inch rockets launchers or two 500-pound bombs located any German ground fire quickly and destroyed the position. It wasn’t until June 19, that the 45th’s organizational equipment finally arrived. The delay was caused by severe storms in the English Channel. Immediately after the equipment had been retrieved, the hospital was established and the wounded began to come in. Many casualties resulted from German tanks firing their huge guns into the hedgerows. The shells would hit the trees (treebursts –ed) and create thousands of wooden shrapnel pieces that would fly through the air in all directions causing multiple wounds.

Most of the admissions at La Cambe were surgical. A large number of the patients were either returned directly back to duty or sent to a Convalescent Hospital or Exhaustion Center for rehabilitation.

Another enlisted men group picture. This photo was taken at St. Sever, France, where the hospital unit was stationed between 8 and 21 August 1944.

On July 2, 1944, nine German Nurses arrived at the 45th Evacuation Hospital. These Nurses, captured after the fall of Cherbourg (DRK personnel and Kriegsmarine auxiliaries), were to be returned to the German lines. However, they did not know until after their arrival at the hospital that they were to be returned. Needless to say, they were overjoyed. These Nurses were well fed but were not in complete uniform. However, their clothing was of good quality. The 45th’s CO escorted the Nurses through the facilities. They had the opportunity to observe supplies and equipment and talk to German patients and prisoners of war. They were most curious about the care and treatment given German patients and PWs in England. They also expressed amazement at the size of the operation and amount of available equipment and supplies. After seeing the hospital, the Nurses were transported in a closed ambulance to Balleroy. Here, there was a wait of approximately two hours while final arrangements were being made with the German Officers (a cease-fire was agreed –ed) to whom they were to be returned. At approximately 1800 hours they were taken through the lines at Caumont-l’Eventé (the above was described in the British Edition of “Yank” dated July 30, 1944 –ed).

Breakthrough at St. Lô:

With the capture of Caen July 7, 1944, the Allies had hoped to have a clear path to Paris. Unfortunately this did not materialize. On July 25, the Americans launched Operation “Cobra”. Its goal was to break through the German lines near St. Lô. By July 27, the breakthrough was accomplished and General George S. Patton’s Third Army captured Rennes, which was a key point of exit from the Normandy region. The breakthrough was completed and the breakout towards Paris commenced.

The 45th arrived at the town of Airel, less than a mile from St. Lô in the morning of July 25. Hospital operations were set up so close to the front that the ground shook from exploding bombs being dropped by Allied planes. Each time an explosion was heard, the canvas on the tents rippled as if they were a wave in water. The area that was being targeted by the Allied Air Forces was so close to the American troops that several “friendly fire” tragedies took place. A total of approximately 100 American soldiers were killed and 500 injured as a result of these strikes. Lt. General Leslie McNair who was observing an attack from his foxhole was unfortunately killed by friendly fire. This infuriated ground forces and as a result, General Eisenhower ordered that strategic bombers would no longer support ground forces.

Partial view of the 45th Evacuation Hospital’s motorpool (WC54 3/4-ton ambulances) while stationed in Eupen, Belgium, from 28 September 1944 until 30 December 1944.

When the 45th EH left Airel, they passed through St. Lô. By the end of the war, this city was nicknamed “Capital of the Ruins” because 95% of the city was destroyed. While rebuilding of the town started immediately after the war, it was only completed in 1962. During the St. Lô breakthrough, the 45th handled almost 1,600 injured soldiers.

Falaise Gap:

By the beginning of August 1944, many German Army units were on the retreat. In a bid to escape, German troops attempted to retreat through a small passage between Argentan and Falaise, known as the “Falaise Gap”. As General G. S. Patton drove toward Argentan, and General B. L. Montgomery’s men captured Caen, General Omar N. Bradley ordered Patton to stop. Bradley was afraid Patton would run directly into Montgomery’s Army. This infuriated G. S. Patton because he believed that if his Army hadn’t been halted, he would have captured every German in the Normandy area. However, since the end of the war seemed to be academic, Eisenhower backed Bradley’s order because he cared little that Germans that were retreating in chaos be captured. As a result, the Germans retreated west of the gap and towards the Orne River. The fighting at the “Falaise Gap” was a great, but incomplete Allied victory.

In supporting this operation, the 45th Evac set up their hospital in St. Sever on August 9. In a period of less than 18 hours, the unit received more than 400 casualties. In total, about 1,000 cases were treated in the course of this action. On August 21, the hospital packed and moved to Senonches, a 160-mile trip. On the same day, the “Falaise Gap” was finally closed but casualties kept coming into the hospital. Almost 1,500 casualties were treated. While in Senonches, Walter was able to have his first “dinner” in France. On August 28, he went to the “Hôtel De La Forêt”. (the hotel and restaurant still exist today). After Senonches, the unit traveled through Versailles, Paris and Soissons without stopping and made its last stop in France at La Capelle, near the French-Belgian border, where it bivouacked. No action was seen at this stop.

Battle of the Bulge:

On September 14, 1944, the 45th Evacuation Hospital sent out a limited number of trucks with the most important equipment, crossed into Belgium and set up a bivouac at Ouffet. The next day, the unit arrived at its destination in the town of Baelen and set up operations in a field in town. The hospital began to receive its first patients on the morning of September 16. A few days of rainy conditions made the ground muddy and the patients and staff uncomfortable. Stoves were used to dry out the ground in the ward tents. It had been three months since D-Day and the number of combat exhaustion cases was increasing. During the eleven days the 45th was in Baelen, approximately 1,500 casualties were treated.

It became obvious that the unit was now nearing Germany because of the attitude of the local people. While on the roads traveling between places further to the eastern part of Belgium, youths threw apples at the hospital’s trucks and staff. Some personnel were treated for black eyes and bloody noses. When the convoy would stop, children would attempt to pour sand into the gas tanks of the vehicles. These children were the product of years of Nazi indoctrination (the eastern provinces of Belgium had been reannexed by Germany after its victory in May of 1940 –ed).

Personnel of the 45th Evacuation Hospital pose with one of their jeeps during winter.

On September 28, the unit moved to nearby Eupen. This move was greeted with elation when it was learned that the hospital was to be set up in a high school. This was a blessing because during the course of the next few months, 7,077 patients were treated in a relatively comfortable setting.

Beginning in October, German V-1 rockets began bombarding the city of Liège, from locations in Germany to the east. Because Eupen was on the course to Liège, the rockets flew directly over Eupen. Nicknamed “Buzz Bombs” by the Allies because of the noise they made when flying overhead, these were a potent weapon in Hitler’s arsenal. They flew at very low altitude, and when the timing mechanisms expired, the engine would shut off and they would fall to earth. During the war, over 9,000 of these V-1 rockets were launched against England.

On November 15, the fourth conference of First United States Army Chief Nurses was held at the 45th EH installations in Eupen. All Principal Chief Nurses and Assistant Chief Nurses were present. The purpose of this conference was to ascertain the status of clothing and PX supplies for Nurses, to reemphasize the importance of bedside care for patients, and to encourage greater efforts toward standardization within units.

At 5:30 am on December 16, 1944, Eupen came under intense enemy fire. The Germans, hoping to capture Antwerp, launched a counteroffensive on the Western Front. This was the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge. By December 24, the Germans advanced 60 miles into the Ardennes. Some damage was inflicted on the Hospital’s buildings, in particularly the laboratory. On December 18, all patients were evacuated from the hospital and repairs started. The next day, an order came to move the hospital so dismantling of the medical installation commenced. The next day the unit moved to Huy, Belgium, but then was ordered to return immediately to reestablish the hospital again in Eupen.

After the return to Eupen on December 21, orders were given to have some of the 45th’s 2 ½-ton trucks assist in an evacuation of the First US Army Depot and the 44th and 67th Evacuation Hospitals from around Malmédy, Belgium area. At the time, not many knew about the Malmédy Massacre that took place a few days earlier on December 17. German soldiers at a crossroads near the town shot eighty American Prisoners of War (some sources indicate 72, other say 84 –ed). Those who were not killed outright were shot or bludgeoned by SS soldiers on the site. Walter recalled that this angered American troops thoroughly and he hinted that going forward, German prisoners were not treated as well as they had been in the past. By January 20, 1945, the enemy was pushed back to where they had started before the offensive. Casualties for the battle were 100,000 for the Germans and 81,000 for the Allies (US losses included 4,100 killed, 20,200 wounded, and 19,600 missing –ed).

Photo taken by Walter J. Kucharski while traveling in one the 2 1/2-ton trucks (part of the 45th Evacuation Hospital motor convoy) crossing the River Rhine, Germany.

Mopping Up In Belgium:

After the major fighting began to wind down after the Battle of the Bulge, the 45th EH moved its operations to Jodoigne, Belgium on December 31, 1944. Again, a school building was utilized as hospital.

During the Battle of the Bulge, First United States Army Hospitals admitted over 78,000 patients including 24,000 wounded. Third US Army Hospitals registered over 70,000 admissions, including approximately 30,000 battle casualties.

Before the organization left Eupen, it received a new Commanding Officer, Colonel Abner Zehm, MC. He was a regular Army Officer who apparently received a lukewarm reception by the unit’s staff. One event occurred that cemented his distant relationship with the men in the unit. The high school building in Eupen, which was used as the hospital, contained a gymnasium. On one occasion, the Officers and Enlisted Men made up teams and began playing basketball in the gym as a recreational outlet. Walter, one of the taller men in the unit played the position of forward. Upon hearing of the game, Colonel A. Zehm stopped it and lectured the Officers about excessive fraternizing with the EM. After arrival in Jodoigne, Belgium, the Enlisted personnel were restricted to the hospital area on January 1 while men from other units enjoyed a pass to the town. Needless to say, this didn’t endure Zehm with either the Officers or Enlisted Men.

On January 19, the unit moved to a new location near Spa, Belgium. The hospital was to be set up in an area that formerly trained horses for the Belgian Cavalry. About 2,600 cases were treated here. At one point during this period, actor Mickey Rooney stopped by to visit.

The Kurhaus at Honnef, Germany, which housed the 45th Evacuation Hospital. This was one of the few luxurious and relaxed sites occupied by the organization.

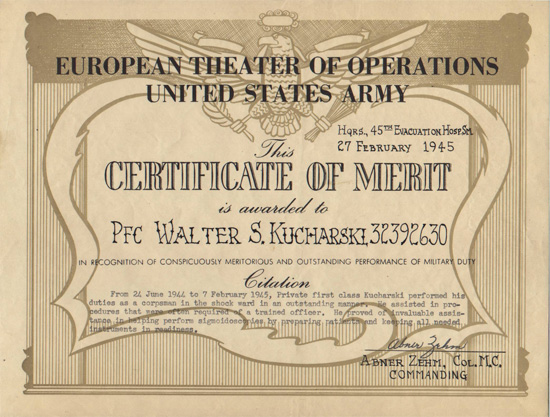

On February 27, 1945, Walter S. Kucharski received a Certificate of Merit. It read:

From 24 June 1944 to 7 February 1945, Private First Class W. S. Kucharski, 32392630, performed his duties as a corpsman in the shock ward in an outstanding manner. He assisted in procedures that were often required of a trained officer. He proved of invaluable assistance in helping perform sigmoidiscopies by preparing patients and keeping all needed instruments in readiness.

(signed) Abner Zehm, Colonel, MC

Entering Germany:

On February 8, the unit moved back through Eupen, Belgium and into Germany. They traveled through Aachen and across the Siegfried Line. The hospital was then set up in Eschweiler. The building used had been a German Hospital and because of the heavy fighting in the area, had been left in poor condition. Here the 45th EH operated for five days as an Evacuation Hospital, and subsequently as a Convalescent Hospital starting on March 13, 1945.

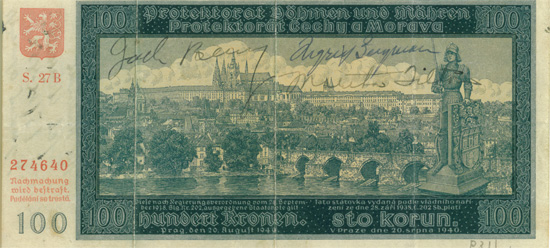

100 Kronen banknote (Protektorat, Böhmen u. Mähren – Protectorate of Moravia, ex-Czechoslovakia), autographed by Jack Benny, Ingrid Bergman, and Martha Tilton who participated in a USO show held at Bad Wildungen, Germany, for the troops.

At this point, the American Armies began moving quickly into Germany. On March 22, the unit moved to Bad Neuenahr on the Rhine River. Soon, it was on the move again. News spread quickly in the 45th that they were to cross the Rhine River at Remagen. As they passed the collapsed Remagen (Ludendorff) Bridge, they viewed the hulking wreck half submerged in the water. For 10 days, American troops crossed this bridge into Germany before it finally collapsed after numerous German attempts to destroy it. The 45th Evac crossed the river south of the bridge where the Army Engineers had constructed a pontoon bridge. The organization then proceeded to the small river town of Honnef. There they occupied a former German Spa (Kurhaus). During this stay, some soldiers from the unit commandeered two large barrels of wine. Needless to say, all enjoyed this luxury during the stay in this town. Upon leaving, the convoy passed a sign that read; “Under Enemy Fire – Keep Interval”. This meant that the trucks were to keep a significant space between each other as they drove from the town.

On April 3, the 45th arrived in Bad Wildungen. The accommodations here were probably the best they ever had during the war. The hospital was set up in the beautiful Badehotel, a resort hotel. Many German soldiers recovering from wounds populated the city. Those able to work were recruited to perform the duties of some American personnel. Being very close to the front, both American and German casualties were constantly brought into the hospital. A total of almost 2,400 casualties were treated during this period. During the stay at Bad Wildungen, a USO show was held for the troops. A stage existed on the hospital grounds and was used for the performance. The show featured Jack Benny, Ingrid Bergman and Martha Tilton. Walter was able to get all three to autograph a banknote and it was rumored that Ingrid Bergman sat on his lap.

The feeling in the unit was that the war was almost over and that a period of long rest was to come soon. However, that was not to be the case.

Partial view of one of the buildings occupied by the 45th Evacuation Hospital while providing medical care and relief at Buchenwald Concentration Camp, Germany. Photo taken end of April 1945.

Only Nazis Kill Like This:

The 45th Evacuation Hospital left Bad Wildungen on April 19 and traveled to Nohra. The hospital was established near an airfield in several battle-scarred buildings. While in operation for five days, 239 patients were treated. On April 22, the unit moved to Weimar, the location of the infamous Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Buchenwald already opened in 1937 and later became part of the “Final Solution” program. During the Nazi regime, 239,000 people were housed in the camp. Of these, about 56,000 were killed. On April 11, 1945, elements of the 80th Infantry Division had liberated the camp. On April 28, the 45th EH set up camp at Buchenwald. This was the first time that the Nurses did not accompany the unit. The scene that befell them during those first days at the camp was incredible. Human beings resembling skeletons walked around the camp. Also, piles of ashes that once had been humans were lying around on the grounds. The gas chamber, the crematorium, the gallows, the burial pits, the stench. Today we can view the photographs of what they saw, but we can’t come close to imagine what it was really like. Walter Kucharski never talked about what he saw here until his son discovered his photographs of the camp. Then he discussed the subject briefly. How can someone talk about a scene such as that? (the noted newsman Edward R. Morrow posted a report from Buchenwald April 16, 1945).

Small group of enlisted personnel posing while stationed at Bretten, Germany, end July 1945.

Upon arrival at the camp, the unit established operations. The hospital was set up in the building that was the former SS Barracks. This building went from housing spawns of the devil to a headquarters for angels of mercy. During the camp’s liberation by the Allied troops, the enraged inmates raided the barracks, killed many of the SS troops and trashed the building. After considerable work, the buildings were made usable.

The camp survivors were evaluated. In addition to being malnourished and infested with lice, many suffered from tuberculosis and typhus. Patients were first bathed and then sprayed with DDT powder, a powerful insect poison. Their clothes were burned and they were given new pajamas. After the camp’s liberation, both the 628th Medical Clearing Company and personnel of the 120th Evacuation Hospital attempted to contain the spread of typhus prior to the arrival of the 45th Evacuation Hospital.

During this time, the citizens of nearby Weimar were brought to the camp and shown all the atrocities committed there. GIs were angered to hear from the villagers that they had no idea of the atrocities occurring there. Items found in the camp included lampshades made from the skin of some of the inmates by the Commandant’s wife, who was referred to as “The Witch of Buchenwald”. Logs of medical experiments, as well as caches of jewelry, currency and gold teeth fillings were discovered. One of those liberated in the camp was Elie Weisel, whose writings after the war about life in the camp won him a Nobel Prize in 1986. General Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered as many German soldiers and dignitaries as possible to view the camp.

The End of the War:

On May 8, 1945, while the 45th EH was at Buchenwald, the war in Europe ended. The next day, “IKE” had his “Victory Order of the Day” handed out to all troops. It thanked the soldiers for the hardships they endured and courage they displayed throughout the war. The 45th’s Chaplain, Captain George W. Zinz, Jr., ChC, also commemorated the day by issuing the “45th’s Prayer for V-E Day”.

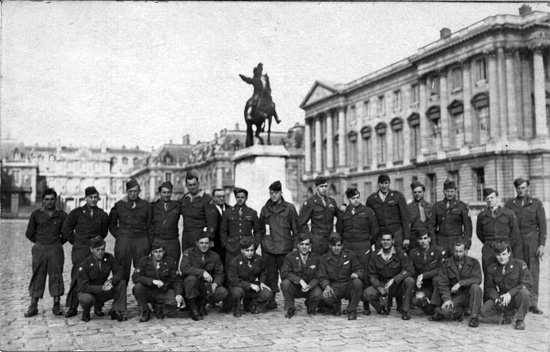

Group of 24th Evacuation Hospital personnel during a visit to Versailles, France. Photo probably taken while awaiting further redeployment to the Pacific Theater or return to the Zone of Interior, in Germany.

Nohra. At this German city, the active service of the 45th took an end. On 13 May 1945 the 45th Evacuation Hospital, Semi-Mobile, was awarded the Meritorious Unit Service Plaque by General Order No. 75, Headquarters First United States Army, for superior performance of duty in the accomplishment of exceptionally difficult tasks during the period from 2 December 1944 to 16 February 1945.

In a letter addressed to each soldier and dated 10 July 1945, Colonel A. Zehm added his congratulations:

By your loyalty and devotion to duty, your professional skill and superior performance, you have brought life, relief from suffering, and new confidence to the thousands of our brave soldiers for whom you so ably cared. To this organization, you have brought an honor as represented in the above citation. A share of this credit is due to each member. However well our job was accomplished, we must not now relax, for big responsibilities still lie ahead of us. It is with much pride and pleasure, that I am afforded this opportunity to offer my deepest appreciation and thanks for the sacrifices you have made and the service you have rendered in bringing this honor to our organization.

(signed) Abner Zehm, Colonel, MC

From that point on until the end of the war with Japan, the 45th EH was uncertain when they would be transferred to the CBI Theater. The unit moved from one city to another in Germany in the role of an occupying Army.

On June 4, 1945, the organization moved to the city of St. Wendel. On July 14 it was off to Schwäbisch Hall where Walter Kucharski was captured in photographs pitching softball. The final city that Walter recorded visiting was Bretten on July 22. The unit relieved the 95th Evacuation Hospital at Bretten and operated as a Station Hospital from July 1 to July 13, 1945. After Redeployment and Readjustment procedures were initiated, high-point men were transferred and new men came in. There also followed a change of command with Colonel A. Zehm being replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Isidore A. Feder, MC. The 45th EH ceased to act as a functioning hospital September 13, 1945 and left Germany by motor convoy on September 23 for the Assembly Area Command, France. Staff and personnel were to stay at Camp Philadelphia and Camp Carlisle, prior to reaching the Staging Area at Camp Philip Morris, France. The hospital finally left France on November 10, 1945, with Officers and EM travelling on board the “Thomas H. Barry”, and the Nurses going home on the “West Point”. We do know that the 45th EH returned to the ZI, arriving at Camp Myles Standish, Massachusetts, November 20, 1945, for deactivation the next day. Walter’s Honorable Discharge papers indeed indicate that he left the ETO on November 10, arriving back in the United States November 20, 1945.

Going Home:

On November 25, 1945, Walter was Honorably Discharged from the United States Army at Fort Monmouth (Signal Corps Laboratory & Eastern Signal Corps Center –ed), Red Bank, in New Jersey. He had served for 3 years and 4 months. He was awarded the Good Conduct Medal, the American Campaign Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with a silver battle star, the World War II Victory Medal and the Occupation Medal with Germany clasp. In addition, he was entitled to wear the Meritorious Unit sleeve insignia and Honorable Service Lapel Button. His official ASR score before Discharge was 85 points.

Epilogue:

Returning to his hometown of Bayonne, Hudson County in 1946, Walter Kucharski began working for the New York Telephone Company. At the beginning of his employment, he worked installing heavy cable beneath the streets of New York. It was a tough job, but Walter was a tough man. Eventually he achieved a high and responsible position within the Company. Many of his tasks in later years involved working closely with CBS Television Company at their studios on 57th Street in New York City. Besides becoming friends with such celebrities as Carol Burnett, Jim Jensen, Bob Keeshan (Captain “Kangaroo”) and Walter Cronkite, he was also a witness to history being made. He would work in the CBS news studios during many of the space flights and national elections.

Walter and Helen Kucharski had two sons, Thomas and James, born respectively in 1950 and 1959. Because of health problems, Walter opted for early retirement in 1976. He enjoyed almost ten years of retirement with Helen, their children and grandchildren. In 1985, after experiencing weakness in his legs, he was diagnosed with a tumor in his spinal column. Although it was benign, the subsequent surgery to remove it left him a paraplegic. For the next six years he suffered both the daily pain from his condition and knowing that he would spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair. For those who knew him, it was the supreme irony for this once physically powerful man. Walter and Helen lived their entire lives in Bayonne. They both passed away in 1991, within three months of each other. Helen died suddenly on June 22, and Walter on September 18. Both were buried together in a mausoleum in the Holy Cross Cemetery, North Arlington, New Jersey.

Certificate of Merit awarded to Private First Class Walter S. Kucharski, ASN 32392630, dated 27 February 1945, and signed by the 45th Evacuation Hospital Commanding Officer, Colonel Abner ZEHM, MC.

We are truly indebted to Jim Kucharski, son of Private First Class Walter S. Kucharski (ASN:32392630) who served with the 45th Evacuation Hospital in the European Theater, for sharing his Father’s WW2 recollections and numerous personal photos with us. Sincere thanks, the MRC Staff.