Memoirs of the American Red Cross Detachment 203d General Hospital

Preparation for Movement Overseas

For a few of us it all started on the 15 of December, 1943, when the 203d General Hospital left Fort Lewis, Tacoma, Washington by troop train for “destination unknown.” After winding all over the US, we, Allaire Stuart – Marian Kurz – Dorothy Ellis – Virginia Beggs, eventually arrived at Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey about 2 a.m. Tuesday, 21 December 1943. After hectic “staging”, the entire unit left Kilmer by train for the P/E on the following Tuesday, 28 December. That day we boarded the “USAT Brazil”, and Wednesday, 29 December 1943, saw us sailing for the E.T.O.

Aboard the ‘Brazil’ some of us played poker and lost all the small change we had been advised to take with us; other promenaded “topside,” and others were slightly seasick. New Year’s Eve was celebrated down in the mess – refreshments were served, and Captain Sadler and General Burnell addressed a few words of New Year’s greeting to us.

England

On Friday, 7 January 1944, we sighted land and on Saturday morning we saw the coast of Scotland, and learned that we were anchored in the Firth of Clyde off Gourock. It was not until Wednesday, 12 January, that we actually debarked and boarded a train for the next “destination unknown”.

At Gourock, the American Red Cross people were detached from their unit and sent to London, while the Hospital unit found itself on the way to Petworth, Sussex County, England. At Petworth, the 203d General Hospital was billeted in Nissen huts which were situated in what had formerly been a Pheasant Copse. Their first introduction to this Camp was discouraging, to say the least, but the entire unit fell to work and cleaned up their new homes. Here in Petworth, they were initiated to blackouts, to alerts, to the hard “biscuits” on the hard cots, and to the Limey stoves. It was here, too, that we learned to drink the English beer and ale.

The American Red Cross detachment of the 203d provides hot coffee and chow for the Hospital staff. Photograph was taken in Paris, during the winter of 1944.

Training classes began for everyone on 31 January. On 3 February, Thursday, the 203d had their first dance in the Club. Notable about this was the amount of soap flakes which had been shaken on the floor to make it smooth for dancing, and the number of people allergic to the suds they created as they danced.

Most of us remember the ‘Angel’ in Petworth, and the ‘Swan’, and the number of walks taken to Petworth for a beer – or “spirits,” if we were lucky. Many of us remember Tillington, one of our favorite hangouts, and where we all crowded into the back room and sat before the small grate fire drinking beer.

On Saturday, 19 February 1945, we all moved out of Petworth and took the 1222 train to London; left London about 1722; and arrived in Swindon about 1915. There in Bradford Hall we spent until about 2215 getting our billet assignments. The first night in Swindon was a rough one – some of the girls found themselves sleeping in bathrooms, on cots with lumpy straw mattresses and on window seats.

What we’ll all remember about our stay in Swindon is the bitter cold. Until the day we left Swindon, 17 March, few of us were ever warm. We all began to take tea every afternoon around three or four o’clock, and we frequented such places as ‘McIlloy’s’, ‘The King’s Arms’, ‘The Goddard Arms’, and some of the little teashops nearby.

A lot of us learned to have a small drink before lunch, the excuse being that this was the only way we could feel even momentary warmth. We went to innumerable movies, good and bad, because we found that the cinemas were slightly less cold than our billet or out on the street.

On St. Patricks’s Day, Friday 17 March 1945, we left Swindon and arrived at our own Hospital site in Burford about 1200 noon. We had lunch and then went back to our new quarters. Eight of us were billeted to a hut, and all of us began settling in and putting things to rights immediately so that we could be ready for our first (but not the last, by a long shot) inspection on the following day.

Most of us were delighted with our new quarters, and revelled in the warmth which the little limey stove afforded us.

It was here in Burford that we began to use the bikes which many of us had bought in Swindon, and the famous combination of the three “Bs” also began here – Beer, Bicycles, Blackouts.

On Saturday, 1 April we had a cocktail party at the Club to celebrate our having received our first NAAFI ration.

Our Hospital opened officially on 15 April 1944, but our work wasn’t really heavy until after D-Day, 6 June 1944. All of us remember the alerts which always sounded after we’d all gotten to bed, and how we had to get dressed in fatigues and tear up to our respective places of duty. Every night in the huts there was always an argument about whether or not we should put our “alert clothes” out in readiness for an alert, or whether we should just make up our minds that this was going to be the night there was no alert!

About the first part of June the usual rumors with the latrine stamp of authenticity started, and daily one heard different – and better versions of when we were going to leave and where we were going.

On the sixth of June the long-awaited D-Day Invasion actually became a fact, and all of us began working very hard. Our Hospital census went ‘way up’ to 900, and we felt that we were really working hard. During the entire period of our operations in Burford, we had a total of a little over 1500 patients. Captain Piatt swore that she had had a dream in which she saw official papers giving the date of the invasion of France. No one can dispute her because she recounted the dream at the breakfast table the day after she had the dream, and told everyone present that she knew that the 6th of June would mark the date of the Invasion. Dream or no dream, the 6 June 1944 had already gone down in the history of this War!

Colonel Oveta C. Hobby (Director WAAC), First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Mrs. John Treadwell (Asst. Director A.R.C.) during a tour of London Red Cross facilities,

November 1942.

It was also in June that the “pilotless planes” began appearing over London and its vicinity.

On Saturday, 24 June, Major General John C. H. Lee (CG Services of Supply, E.T.O. -ed) appeared on the scene and the Hospital was in a quiet turmoil until he left. Through all this time we had countless Hospital units staging with us on the Post, and our Officers’ Club seemed in imminent danger of having the walls collapse from the pressure of the crowds milling around inside. The 203rd Gen Hosp reacted well to the presence of so many strangers, the immediate result being that we were drawn closer into a more cohesive group. Life in the 203d General Hospital was like life in a large family – we felt that as members of the family, we could gripe and criticize, but woe to the outsider who infringed upon our privilege.

On Monday, 10 July, the 203d moved again. The night before had been spent in hectic preparations – packing Valpacks or suitcases, and trying to pack our bedrolls so that they conformed to the required size and didn’t resemble overstuffed mattresses – that some of them did, goes without saying. Our footlockers had gone two or three days before, and we had tried to put in them articles which we would not need for a long time. That we were only partially successful in doing this, we found out later on. At any rate, we were up at 0500 the next morning, had breakfast at 0600, and finally left the Post at 0900. We got off the trucks at the Brize Norton Station and boarded the train. Our journey took us through Oxford, Swindon, Taunton and finally to Exeter. We had had no food since six in the morning, and all that we could think of as we got into the trucks which were waiting for us at the station, was what we would be having for supper. But food was a long way off, had we but known it, because we were taken to a Camp outside Exeter and left there to think about our hunger.

The Camp in which we found ourselves was in considerably worse condition than our Base at Petworth, and we learned that this one was in the process of being torn down by the Engineers. We felt quite lost and rather forlorn, and the cold drizzle of rain which began to come down did little to improve our morale. However, we revived sufficiently to dig up some raw potatoes which some enterprising gal had discovered and to peel them and eat them. As we sat there huddled together amidst our helmets, musette bags, gas masks, pistol belts, and other similar trappings, we munched our raw potatoes and began dreaming up a few wild conjectures as to why we were in this condemned place and what would happen to us next. Not too long after this, the trucks came after us again and we struggled into them, hoping that this time we would arrive at the correct place.

About 2045 that night saw us sitting down to supper in our new Camp at Exeter, and never was food more welcome. After eating we came back to the barracks to see what could be done to clean them up a little bit for our occupancy. However short the time which we stayed in any one place, we always began housecleaning and trying to improve upon our living conditions a little. Here we were sleeping in double-decker bunks on straw ticks, but none of us spent a sleepless night that night. On Tuesday, 11 July, began a stream of Nurses into Exeter to get permanents – for who knew into what wilderness we were going! It is plain, therefore, that not only did we try to improve upon our living conditions, but that we also tried to improve upon our personal appearance – and in all these efforts we were encouraged by our Administration.

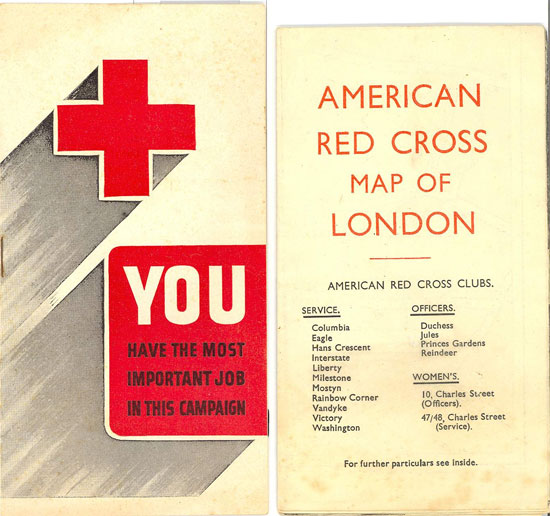

Right: American Red Cross Map of London, with underground stations, places to see, theaters, cinemas, and A.R.C. Clubs

Left: “YOU Have The Most Important Job in This Campaign”, A.R.C. Leaflet to motivate campaigners (ref. ARC 1136 – Dec. 1945)

On Thursday, 13 July 1944, we received our orders to leave in any minute, and we were all packed and ready in an hour. We left at 1450, went by truck out of Camp, took another train and went through Salisbury to Romsey, and from there further into the marshalling area. We reached the place at about 2100 and had something to eat at the mess, and then got settled in our barracks. This time we slept on Army cots and there were about thirty-some-odd girls to each barracks. That night we had our first experience with the “doodle bugs”. Three times we were awakened by the peculiar putt-putting of the buzz bomb motor, and we lay there waiting for the motor to stop and wondering all the time whether or not the filthy thing would land on our barracks ……. The next day the expression came out, “Hysterics in the Barracks” but this was a little exaggerated.

At the marshalling area, our Officers’ Club had its Headquarters among stacks of old, dilapidated double-decker beds. Here on and under these beds, the 203d met to play cards, gossip and to take sunbaths. Most of our time was spent in activities like these, and in watching the famous Black Watch parade to the skirl of the bagpipes and to the rhythmic beat of their drums. Periodically during the week, we lined up to receive such interesting items as louse powder, anti-seasickness tablets, pills for purifying water, K-Rations, and D-Rations. One evening we had to line up and turn in all our English money so that we could be issued French currency in its place. Our days and nights were always interrupted by the sound of the P.A. system blaring out the numbers of the various units at the marshalling area. We would stop talking, or doing whatever we were doing, and listen intently for our own number, 2667 B-1, to be called. If our number was called, we all thought that we were going to leave.

On Thursday, 20 July 1944, our orders did come through, and we left a little after 1200 in a convoy bound for Southampton. Here, after some waiting around, we were marched on to the “Duke of Wellington”, an English ship. Billets for the men were not all that they might have been, but we were aboard ship only two nights so that any hardships suffered were transitory.

The English opened their bar and we bought tickets which entitled us to a certain number of bottles of ale. We did not leave our anchorage point until 0300 of 21 July. We were not able to land when we did arrive off the coast of France, because the Channel was too rough. Many members of the unit who hadn’t been at all seasick crossing the Atlantic found themselves slightly green and definitely uninterested in food during the crossing of the Channel.

France

On Saturday, 22 July 1944, we got up at 0600, had breakfast, and were ready to leave the “Duke of Wellington” for an LCT. The officers and EM were loaded into boats before 0800. We strapped on all our gear and then slid down a chute into the LCT. We had to remain on the LCT from about 1030 until 1500 – first we had to wait until the tide came in so that we could get closer to shore, and then we had to wait again until the tide went out so that we could walk off the boat onto the beach.

After landing, Army trucks took us first to Area H, and then finally to our Camp with the 8th Field Hospital right by Emondeville, south of Montebourg. Here we were to live in tents, sleeping on Army cots, and eating K and C rations. We began exploring the Camp area right away, and our first object of curiosity was a German tank which had been left just down the road from the Camp. Before we left, it was undoubtedly the most photographed item in all of Normandy. Before we set out for walks around the countryside, our ears rang with admonitions of our superiors about being careful and to walk on the road and never to stray into the fields, etc. While we were camped here with the 8th Fld Hosp, some of our personnel were sent out on detached service.

It was while we were here too, that we really suffered air raids, and the earth beneath us seemed to tremble and our ears rang from the concussion of the nearby anti-aircraft guns. We can still hear Colonel Baker shouting “Air Raid, Air Raid” over the din of Jerry motors and of our ack-ack. In the mind’s ear, too, we can also hear the guards yelling, “For Christ’s sake, DO something! Get into a foxhole, or something.” We can also remember a few of the Nurses having a little difficulty putting their helmets on – some had left their laundry in their helmets, and others had forgotten to empty the dirty water, and still others had forgotten where they had put their helmets. What a scramble!

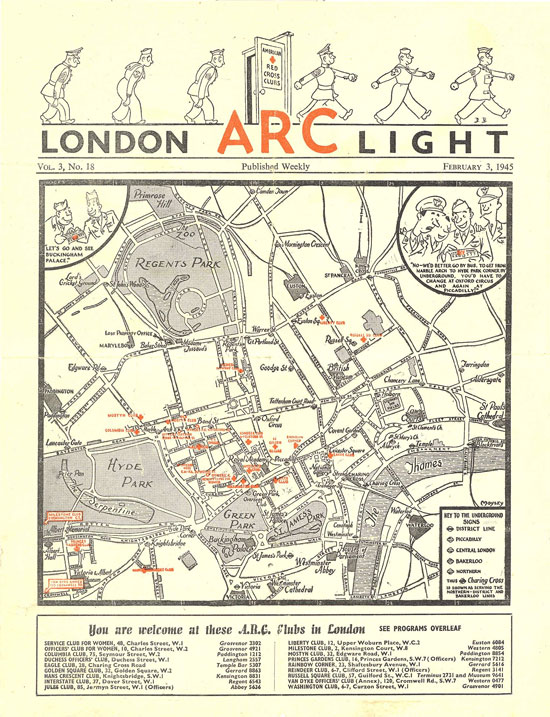

“London ARC Light”, Vol. 3, No. 18, Feb 3, 1945 – weekly Bulletin distributed by the A.R.C. highlighting program features at the American Red Cross Clubs in London.

We had our first showers in the field on Sunday 23 July – a QM shower tent was set up down the road and we all marched down there and went in 18 at a time for showers. We weren’t allowed to waste any time taking the showers, and we were probably the saddest looking bunch of sad sacks that this Army has ever seen – fatigues or combat suits, steel helmets – minus the liner. We wore the helmets as shower caps, and they came down below our ears, giving us the appearance of misshapen mushrooms. Those were the days, you bet!

On Thursday, 27 July 1944, Colonel Turner told us that we would be moving by train, and on Friday, 28 July, we were ready to leave by 1100. We went by trucks to Montebourg and took the train from there to Cherbourg. We were told that ours was the first unit to move as an entire unit by train in France. At Cherbourg, we were taken by trucks to our new Camp near Tourlaville. Ward tents were set up for the women, and we moved in bags and baggage. There were about 22 of us to a tent, but by then we were all used to the enforced intimacies of life in the field. A tarp was stretched around poles to prepare for an ablution place, and eventually we could even brag of a Chic Sale which would accommodate 8 people!

We had our mess in the next field and we ate outdoors, although a few days before we left this site we did have a mess tent where we could sit on benches and eat at tables. We had fun at Tourlaville – swimming in the English Channel, parties nearly every night, and lobster ditto. Definitely, we didn’t suffer any pain while we were here. Good weather, good GI food, supplemented by French cooking, plenty of parties, and outdoor life. We explored the Château of Digosville from top to bottom, went through all the barracks where the Germans had been, and lugged back to Camp every size, shape and description of souvenirs. Our families at home must have wondered what was going on when they received old, beat-up Jerry helmets, shells, insignia, old ammo boxes ad infinitum. Well, we had fun getting all that stuff, and at the time it was exciting!

Along the Normandy coast, another phase of our interminable explorations included the forts which dotted the coastline. They looked impregnable to our eyes, and we now understood the obstacles which our soldiers had had to surmount to take Normandy. Everywhere we went we saw the signs, “Mines cleared to Hedges’, and in some areas there were still the Jerry signs with ‘skull and crossed bones’ warning of mines.

It seemed to us that we took showers all over Normandy – for awhile we took them over by some tiny little village, then we took them at an Engineers’ installation near us, and finally we worked up to private showers down at the bathhouse in Cherbourg. We were clean, at least!

Small Leaflet distributed to Servicemen and women prior to leaving for overseas … (ref ARC 1245 – Oct. 1943)

Even in the field we had a lot of comforts – transportation was available for trips to the Cherbourg beauty parlors, and those who missed out in Exeter on permanents got them eventually in Cherbourg; we also had daily transportation down to the beach below Bretteville for swimming. One of the EMs would even cut our hair for us.

On Saturday, 19 August 1944, it rained all day, and our tent was slightly inundated. We finally had to have a trench dug around the front of the tent so that the water didn’t come pouring in. Inside we lit the Jerry candles that Lucy Nimiro had pried out of a Major, and sat around and had a few drinks. Perhaps it should be noted here that we learned the E.T.O. style of “gold digging” while we were out here in the field. We all had certain items which we needed to make our lives more comfortable, and we would figure out which of our escorts would be the most likely to have access to whatever it was that we needed. Ebba Carlson came back with a very fine railroad lantern which added a great deal to our tent in the way of light. Someone else was planning to get some 100 octane gas to use for cleaning our clothes from one of the Air Corps Officers, and others of us were content getting Jerry souvenirs. Everyone did very well in her “gold digging.”

On Monday, 21 August, it rained again so we stayed in our tent and dreamed up a fine cocktail party, complete with hors d’oeuvres! On Tuesday, 29 August, we moved again. We packed and at 1600 we piled into Ambulances and drove into Cherbourg to take the train. For the first time since we had been with the unit, we had to carry our own luggage, and doing this was no small feat. Most of us had collected so much junk that we were really loaded down, and we had to make several trips from where the Ambulances had unloaded us to where we were going to be on the Hospital Train. We must have been quite a picture as we struggled along the blocks and blocks of train cars. Some of us stayed in a box car sort of thing, while others stayed in the coach part of the train. As it later turned out, those of us who were in the box car had a much better place because we could at least stretch out. At night, the group of us in the box car arrayed ourselves in rows on the floor, and every time anyone moved during the night she tangled with someone’s feet or head. Like everything else we had ever done, given enough time we could figure out some way to be comfortable. Before our trip was finished, we had gotten everything worked out to a system, and we had slung some of the litters and put a few of the girls up on them. This relieved the congestion on the floor so that the rest of us could be a little more comfortable.

All the way down, our train poked along, stopping more often than it ran. Everytime the train stopped, we would open the doors of our car and barter with the French for fresh vegetables and fresh fruit and eggs. Then when the train made a long stop, we would all climb out, build a little fire, and cook a nice stew with the onions, tomatoes, and potatoes we had gotten in exchange for Ration cigarettes, or the D Ration chocolate bars. Our trip proceeded in a very leisurely fashion, so that we were actually on the Hospital Train for three nights and almost four days.

12 Coupons for purchase of snacks, sweets, or drinks at local A.R.C. Clubs, valid for France, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and Germany (note indication of national currencies). Late war issue, probably 1945.

At 1830, 1 September, our own trucks met us and drove us the rest of the way to our new Hospital. After roughing it in the field and after having had a somewhat arduous journey, we were hardly prepared for the luxury of our Hospital. Most of us had the feeling that it was too good to be true, and that we would get orders to move on before very long.

That night we were given our room assignments and everyone spent most of the first evening going into ecstasy over the hot and cold running water right in our own rooms, the real beds with sheets on them, the bathtub, and the real bathrooms. We could scarcely believe that there were now to be no more Chic Sale affairs, no more baths out of our steel helmets, no more reading and writing by candlelight, and no more fatigues. We couldn’t believe our good fortune, and when we saw our new mess hall, we went into further rapture, silverware and china! Not too long after we settled here, we began earning every bit of our luxury, and at the present time, we should think that we had paid our rent in full!

The second of September saw our personnel on the wards throughout the Hospital, cleaning up and getting ready to receive patients. On 3 September we began receiving patients and our work in France had really begun in earnest.

As in England, we were not long left alone to enjoy our fine quarters and Hospital, but soon had units staging with us. The results were more or less the same as they had been in England, serving to draw us together and to make us a little more clannish.

On Tuesday, 12 September 1944, we had our first real dance at our Club, and this marked the beginning of weekly dances each Saturday. On Saturday 9 December, we had a Command Performance Dance at the Nurses’ Quarters to celebrate Colonel Turner’s birthday on the following day.

It is interesting to note here that we had all thought we were busy in Burford, but our top census for any one day was only 900, and during our entire period of operation we had only a little over 1500 patients. In one day here we had admitted over twice that number! Primarily, of course, we worked as an evac here, and each day saw a tremendous turnover. We all worked hard, but few of us minded because we felt that we were really doing something to help.

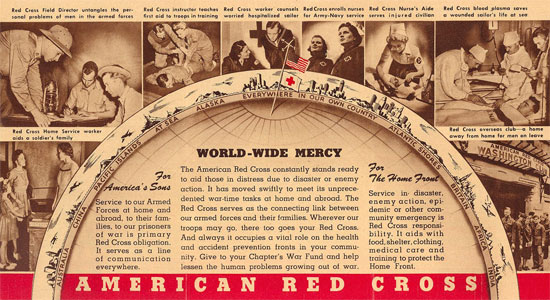

Open view of American Red Cross “1943 War Fund Campaign” Leaflet highlighting A.R.C. nation-wide and overseas activities for the period between January 1, 1942 and February 28, 1943, printed in 1943.

On Wednesday, 27 December 1944, about 2300, we heard the sirens for the first time in many months and learned the following day that a couple of bombs had been dropped on the Gare St.-Lazare. As of that day, Paris was under heavy guard, and anyone who went in on business was stopped by the MPs and interrogated. Questions asked ran something as follows: “Who had a little lamb?” “What state are you from?” “What’s its capital?” “How much is a bottle of coke?” ad nauseum. These questions were changed frequently and were designed to trap any Jerries who were masquerading in American uniforms.

During the latter part of February 1945, the 203d General Hospital began losing some of its family – Colonel Runkle, Colonel Tackney, and later, Colonel Bate, were transferred to other Hospitals. Some of our Nurses had left too – some for Hospital Trains, some to go up with an Army, and later, some who returned to the ZI.

On 13 April 1945, we learned of the death of President F. Roosevelt, who had died on the previous day, and a week or so later we read the news of Ernie Pyle’s death in the Pacific Theater. We felt as though we had lost close friends.

On 8 May 1945, the end of the war with Germany became official and VE-Day was on. Paris went wild that day, and for two days afterwards. All our personnel were given extra time off to go in and see Paris and celebrate. For us VE-Day meant little because in all our minds nagged the question. “What will happen to us now?

On Friday, 1 June, our footlockers were delivered to our rooms, and many of us had the feeling that their arrival marked the beginning of another chapter in the adventures of the 203d. Not too long afterwards – 19 June 1945 – we heard that on 10 July, a year to the day that we pulled out of Burford, we would leave Garches. We understood that we were to go to a staging area, and eventually were to go back to the States. Before the unit arrived at the staging area, however, we would see many more changes and many of us would be sent direct to the Pacific. Such are the fortunes of War.

For all of us breaking-up comes as a real personal blow – we have been together a long time and we’ve worked hard together and played hard together. We’ve griped a lot at times, and there have been times when we have felt that we were abused and misunderstood. But when it came right down to brass tacks, most of us would never have swapped our Hospital with any other one.

So, my friends, wherever you are, whatever you do, remember that we’re all thinking of you and wishing you the best of everything.

Shoulder-sleeve insignia worn by members of the A.R.C. (American Red Cross Volunteer and American Red Cross Military Welfare Service).

Yours faithfully,

The American Red Cross Detachment, 203d General Hospital; Allaire STUART, Marian KURZ, Dorothy ELLIS, and Virginia BEGGS …

This history, one of the best known, was written in 1945 (approximately) according to Allaire Stuart. A copy was forwarded to Colonel William Baker in Chicago. And others have used it as a reference for their own war chronicles.

The authors would like to thank Dan Leary (ASN: 39232383), (X-Ray Technician) who initially collected the original text from which this Article is derived, in his collection of

203d General Hospital Testimonies entitled “203rd GH: An Anthology of Members.” We would also like to thank him and his family for their kind donation of some of

the images which appear in this Testimony.

The authors would also like to recommend the excellent website dedicated to the 203d GEN HOSP, which includes a detailed history and a plethora of images relating to the unit. It can be found here.