Veteran’s Testimony – Wallace Wesley 240th General Hospital

Photograph showing 1st Lt. Wallace Wesley (M-2169) in the Physical Therapy Clinic of the 240th General Hospital.

Introduction & Enlistment:

I was teaching public schools in in Dowagiac, Michigan in 1943. At that time I held a B.Ed. degree in girls’ physical education, biological science and social science from Illinois State University at Normal Illinois, and a MS from the University of Oregon in Health Education. Uncle Sam was looking for people with my educational background to go to Physical Therapy school. The therapists in military hospitals were civilians at that time and more were sorely needed. I enlisted in March 1943. The program required that the volunteer join the WAC (Women’s Army Corps –ed) for basic training and then attend a 9-month school of Physical Therapy. Upon completion of the schooling the volunteer was discharged from the WAC and sworn into the Army Medical Corps for active duty.

Training:

I was sent to Fort Oglethorpe, located 5 only minutes from Chattanooga, Tennessee, and approximately 90 minutes north of Atlanta, Georgia (WAAC/WAC’s Training Center -ed) for basic training. We marched, learned how to make square corners on our bed sheets, went to class, served on KP and worked assigned jobs. My job was to interview incoming WACs for assignment. What recruiters had told these kids they could do (such as fly a plane) resulted in disappointment to many when they learned the truth.

Exterior view of the barrack rooms at the Third WAAC Training Center, Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia.

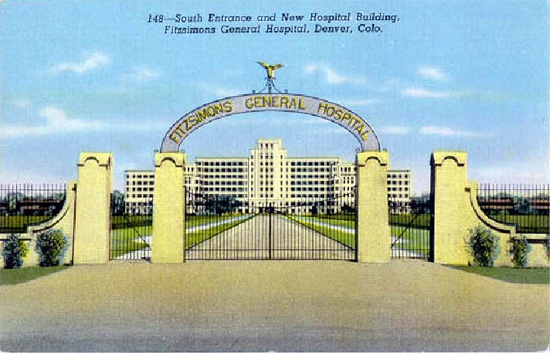

The WAC decided I was needed where I was, so it was slow in sending me on to Physical Therapy School. I finally arrived at Fitzsimons General Hospital (Denver, Colorado) for a 9-month course and graduated in November 1944, being commissioned a 2d Lieutenant.

This was an excellent education even though I already had taken most of the science, including dissection anatomy, previously. The faculty was of good quality and the varied and practical hospital duty was useful experience. The only time I almost passed out was during an autopsy. The smell and the sawing of the skull were tough to observe!

When I graduated, my orders gave me leave for the first time in a year, and directed that when I returned to Fitzsimons I would head the exercise program in Physical Therapy. I was home only two days when a wire came. The current head had orders for duty overseas, but her father became seriously ill, and I was ordered back from Leroy, Illinois to Denver to take her position. In other words we switched orders. I was supposed to have two physicals as part of my discharge from the WAC into the Medical Department. Even though this change in duty was being done in a short timeframe, the Army “could not break rules” when discharging me and so I was given one physical exam on day one and returned and had a similar exam on day two, to meet its requirements.

Color postcard illustrating the south entrance and hospital building at the Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colorado.

I joined a troop train traveling to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey for embarkation. We sat in a Chicago railroad yard overnight. When we finally arrived at Kilmer it rained constantly for four days but at least we had heat in our quarters, which was the last time for some quite a while. We were given shots, issued clothing, went to classes, worked and waited. The food there was lousy! Vera Healy, Pauline Trapp, Mary Moran, “Swede” Everett and I took a pass into the town of New Brunswick and bought some food. On 20 November 1944, I was assigned to the 240th General Hospital.

Movement Overseas:

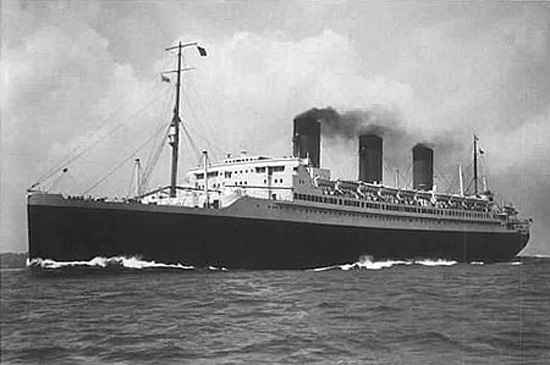

Orders were finally received on 27 November 1944 that the unit was to embark on its overseas voyage, as per Secret Order ASF, NYPE, Brooklyn, NY of the same date. On 30 November 1944 we were finally trucked to New York City and boarded the famous SS Ile de France ocean liner which had been converted into a troop ship. Bunks were in rows stacked at least 5 high in each “stateroom”. We sailed a zigzag pattern to avoid detection by the enemy. The ship was big and fast and did not sail as part of a larger convoy. The first day out, we were hit by storms. Many were seasick, including yours truly. While undergoing this gastronomical upheaval I met Sylvia Brussant who was to be my best friend in the unit. When we had our sea legs, we went up on deck and sat down cross-legged to get acquainted, played cards and watched the ocean. The crew was English and we had English cooks (and food) and Nurses on board too, plus Canadian Army personnel.

Exterior view of the SS Île de France, a French ocean liner which acted as a troopship for members of the 240th General Hospital.

England:

The Île de France landed up the Clyde River in Scotland on the morning of 9 December 1944. The good ladies there gave us tea with milk as we boarded a train. We had been ordered into England where we were to wait our turn crossing the English Channel into France. The train was cold, slow, and the plumbing soon out of whack. My C rations even ran out! We were loaded on buses and ended up at Peover Hall in Cheshire, England. The estate included a beautiful stable, church and graveyard, tenant farmers and some pasture land. The Enlisted Men were in tents; the female personnel (Nurses, Physical Therapists, an American Red Cross Worker and a Hospital Dietitian) were in the manor house – it was cold! There was no furniture, no fuel for the fireplace, no water and the windows were blacked out. We finally found a bit of coal stored up in an attic.

View over the Clyde River from the deck of the SS Île de France.

While there we walked, marched, were loaned to hospitals in operation in England, went to church and got acquainted with the local farmers who were in need of several things, especially soap. We shared. When they knew us better they asked why America had not come sooner.

We froze. One put on all their clothes plus a stocking cap and boots to go to bed. You were issued two army blankets. All clothes including underwear were a lovely GI color!

We spent Christmas 1944 there. Holly berries were right outside so we decorated with them. The chapel service (High Episcopalian Church) was beautiful. One day some girls and I were out decorating the sign to the post, for Christmas, when a jeep with a British Army Officer stopped. He asked what we thought we were doing. I saluted and gave my name and rank. After hearing me speak, he said “Oh, a damn rebel,” and drove on!

We landed in England in time for both the “ticking” bombs and the silent ones (V-1 Flying Bombs –ed). Even though not recommended, we rushed outside to see if we could see the “Tickers”. We could tell by the sound if they were running out of power or were going on by.

Wallace Wesley and two other unidentified members of the 240th pose in front of the Church in Peover Hall, Cheshire, England.

France:

On Christmas Day, 1944 we were transported to southern England (14th Port Staging Area per VOCG UK Base APO 413 US Army -ed) to board a Channel boat. We arrived at the Staging Area the following day, and crossed the Channel on New Year’s Eve 1944. I carried my bedding roll, clothes rolled inside, on my back. Mary Murphy, one of our “fun” Nurses had a huge bedding roll that reeked of salami. The Enlisted Men gladly carried it and later shared in her sausage! We wore combat clothes and boots. The White Cliffs of Dover in the setting sun were beautiful as we left. We were told not to sleep and it paid off; a boat ahead had been sunk. We docked at Le Havre and began debarkation.

The town was flat – a devastating scene. Some of England that I saw was also flat of course, but not like this. This was really flat! Trucks took the women to Étretat, to a château which again was cold, no windows, no heat, no water, no furniture, etc. By then we were old hands. We headed for the kitchen where there might be a stove and fuel but no luck! Stove, yes; fuel, no. There was none outside either. The movement was completed on 1 January 1945.

The Engineers had been ahead of us as had our Enlisted Men. Their tents looked better than a castle to us. They had food for us, bless them. We carried our own mess gear – metal spoon, knife, fork, and meatcan. We ate one meal per day and went through the line for food, then lined up again to clean our gear. We dipped the whole mess kit into immersion heaters to clean and rinse and then hung them in our personal area to dry.

I didn’t smoke; however I took my ration of cigarettes to trade for candy bars (another ration). We had huge Lyster bags of treated drinking water, not good tasting but safe. Keeping personally clean was a problem. We melted snow in our helmets or begged water from the kitchen to wash our hair and bathe until gang showers were available. We washed clothes too, but not often because drying them created another problem – they froze!

One soon learned to wear toilet paper in the top of one’s helmet liner – you never knew when you might need it. Uncle Sam did not issue washcloths so we learned to wash with our hands or cut up a towel. We needed towels so usually we did not cut them up. Of course we had GI colored soap. Sure glad for that no matter what color.

The Battle of the Bulge with retreating units, men and equipment, caused us to wait some more. After only a few days we were moved to Rouen, France, arriving on 7 January 1945. Women as usual went to another castle with blown out windows and nothing much else. There was snow on the ground but we exercised and marched outside anyway. I was impressed with the way Reims Cathedral was sandbagged high up over its stained glass windows. We were loaned out to hospitals set up in the area that always needed medical personnel. I went to the 179th General Hospital. A Frenchman found an old stove for us that had no pipes which we tried to make out of empty cans, and stuck out a blown out window but it didn’t work. It produced more smoke than heat, but at least we had some warmth and felt a bit more comfortable. Again we wore all our clothes to bed.

We found boxes of accurate model airplanes for both American and Russian Forces in one building near the castle. Apparently they were left by the German Army on its way out. These were given to the Intelligence Unit.

Even though we were under stress, we were very aware that we were “in clover” compared to the fighting men in foxholes under fire, or in hospitals, or who were prisoners of war.

The 240th was shipped by truck and train (the famous 40 and 8s) to Nancy, France on 16 January 1945. The Engineers, who were ahead as usual, had selected a boys’ boarding school campus (a walled compound) to establish our hospital and living quarters. There were four other General Hospitals in Nancy. We were all busy, but we had French civilian workers to help us out. As I was assigned to teach French women how to roll bandages, my high school French came in handy! Our cooks worked hard to maintain a mess for our French help and other French citizens who were hungry, for our patients, for our own personnel, and for any soldiers who dropped in and wanted food. We had German prisoners on the compound also working – we fed them as well. The French loved peanut butter and had fun saying “chick, chick” to us when we ate corn (we had lots of canned vegetables).

Exterior view of the 240th General Hospital’s facility at Nancy, France.

When on duty, Nurses and Physical Therapists wore wraparound, brown and white striped seersucker uniforms and caps in the General Hospital. We had to wash and dry our own uniforms.

Sometimes when personnel went on R and R, Physical Therapists would be placed on detached service with another Hospital unit. In one of those instances, when I was in Epinal, France, I was close enough to the front line to see the red glow of battle and hear the low rumble. My main assignment was to work with men who had gunshot wounds through a lung. Not a pretty sight but you can teach men to breathe through one lung only.

The 240th was buzzed by the enemy once – GI patients dived for cover. Our Commanding Officer was Colonel Henry Smith, MC. He was an excellent leader, not a strict “military man”. His main interests were the patients and that the rate of infection for those in our care be as low as possible. And it was low. We had a skilled, thoughtful, kind physician, Dr. Carpenter from Michigan, who was Head of Surgery. Our Medical Officers were a fine group of skilled, caring people as were the Nurses, PTs, American Red Cross Worker and enlisted personnel. The 240th functioned well.

Dr. Smith found us an ice cream machine! What a treat for everyone. It even tasted good made with powdered milk. How we longed for a glass of real milk!(First thing I had when I went to Switzerland after the war!)

Our clinic had two PTs and two Enlisted Men who helped. They were excellent and creative. They made equipment that patients could use in self-exercises, such as a small log with a long handle attached, for a soldier to exercise a healing foot or ankle They willingly worked at massaging, scrubbing, etc. PTs organized classes for patients with gunshot wounds through the hand. We tried to teach them that a hand that moves is best. If a hand remained somewhat stiff the patient needed to work to maintain a thumb-finger opposition. Our peak of operation saw 239 patients at one time.

While I was in Nancy my brother Roscoe, who was in the Quartermaster Corps, was “snaking” a disabled tank out of an area near the front line when he saw the number of my Hospital (Hospital designations were posted as road signs for the troops to follow when transporting the wounded). He went AWOL and followed the route to the facility! Later he came on a pass and spent time at my unit in Nancy, France. He used to joke that he was the only GI who had to salute his sister because she outranked him (by the end of the war I was a First Lieutenant).

Wallace poses for a photograph with her brother, Roscoe in Nancy. Photograph taken in 1945.

Our Nancy compound was large enough for us to play softball, which we did when we had time. When we went outside the compound we were not allowed to fasten the chinstraps to our helmets because an enemy sympathizer might use them to snap our neck to kill us. Sometimes the alcohol that kids would sell GIs was of a dubious nature causing a few deaths or blindness among some of our GIs.

We treated battle casualties, both American and French and also had some French civilians. We were not actually on the front but the wounded troops — fellows with injuries to three limbs, unusable hands, nerve damage – were enough to make you know that war is absolutely no good. News of the brothers of our own unit members being killed was not eased by what one saw go through the hospital. We handled our soldiers who had been Prisoners of War: some had been detained in PW camps or enclosures for 5 years. They were in sad shape – some were a mass of sores from lice, dirt, etc. and weighed around 80 pounds. One boy had lain in a foxhole for 7 days before he was picked up with frozen feet and a broken leg. One could hardly recognize his foot when he reached us. These patients were soon sent to the States by air.

Nancy was a beautiful old walled Roman city with lovely gates of entry and nice parks. We were still there when WW II ended in Europe. We went up above the walls to see the lights come on after six years of blackouts along with the local families there. The children were in such awe, that they were silent at their first view of a lighted Nancy. Adults wept, including me.

After the war ended we were soon moved to a tent city in Rouen. There were so many Hospitals there that we had street names and tent numbers. Later the 240th was set up again in Paris at the permanent American Hospital (located in Neuilly-sur-Seine –ed). We treated GIs who had car accidents celebrating the war’s end, or gunshot wounds from souvenir guns; prisoners of war, other soldiers and some civilians. One of my assistants was a 15-year old German prisoner. I soon knew his family through pictures. He was a nice boy. When I went to a prisoner of war ward I took him with me to translate, as well as a guard with a gun. We had a few SS patients who never cooperated with their care even though they were well taken care of and well fed. Not at all like the regular German soldiers.

We moved to Garches, France to take over the 36th General Hospital. Garches is a suburb of Paris. Paris was beautiful. We saw the Louvre and Arc de Triomphe, climbed the Eiffel Tower, saw Notre Dame and the flea market. We went to see the Folies Bergère (French music hall and cabaret), and learned all about the black market. We paid extreme prices for souvenirs. Paris had dog races, horse races and street cafes – people, people, people! It was also dirty, crowded and expensive. There was no love for the GIs particularly but it was interesting and beautiful.

Main entrance to the 36th General Hospital facility in Garches, France.

While in Paris I had a leave to visit Switzerland. I shall never forget the clean, beautiful country. The people were friendly and English speaking for the most part. High points were seeing Lake Geneva, the Legation of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Lucerne Bridge, and especially the city of Berne. I went with another Nurse “Johnny” Johnson (later Green) and we met up with three GIs who accompanied us. One young fellow blew through his money pretty fast. So I took over handling it for him, doling out a small amount to him each day. Otherwise he would have been broke!

Return to the ZI:

In December 1945 I was sent to Camp Philip Morris for staging to come home. We arrived home on 16 December 1945 in a storm. How great to see the Statue of Liberty, hear the whistles and see the people. How great to reach Leroy, Illinois. I left as a green small town girl even though I was older than many others. I came home a different person and yet the same. I hold great love and respect for our men and women who laid life on the line during the war – those who came back and those who died. I appreciate the work and worry of our home folks. My parents had three children in service and one daughter a secretary to the Chief Chaplain at Chanute Field (home to the United States Army Air Service Technical Training Command and located in Rantoul, Illinois).

Members of the 240th General Hospital unload from the transport ship which brought them back to the Zone of Interior on 16 December 1945.

I love America with all her shortcomings – when one sees other places with the same problems, one blesses the good ol’ USA.

Editor’s note: Wallace sadly passed away on 28 June 2009.

Our most sincere thanks must go to Sylvia Khaton, niece of 1st Lt. Wallace Wesley, PT (M-2169) for kindly sharing her Aunt’s story of her time and experiences with the 240th General Hospital during WW2. Sylvia also provided us with a number of original illustrations for which we will be forever grateful.