Veteran’s Testimony – Michael Rudolph Freeland 22d Hospital Train, 307th Airborne Medical Company

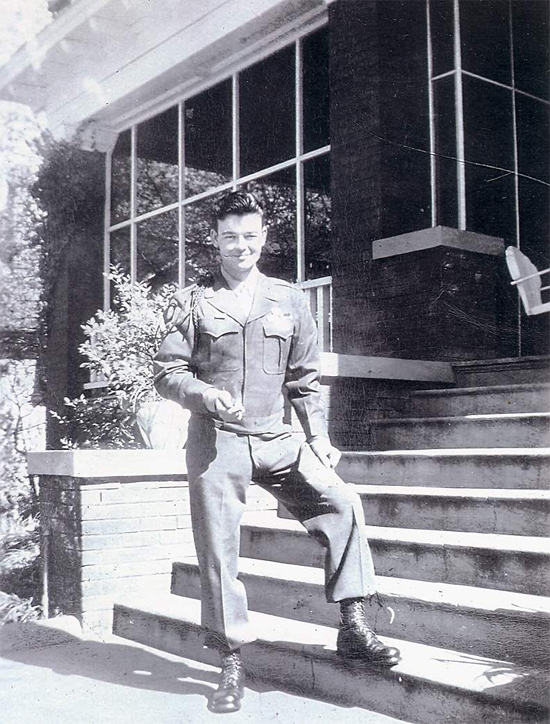

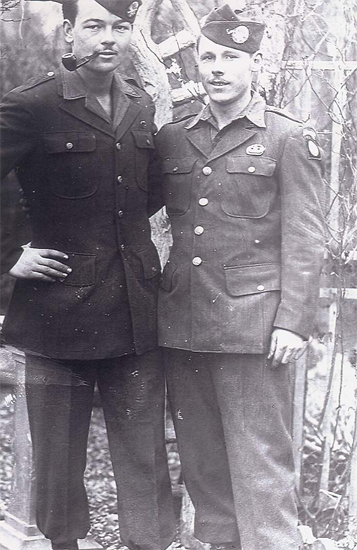

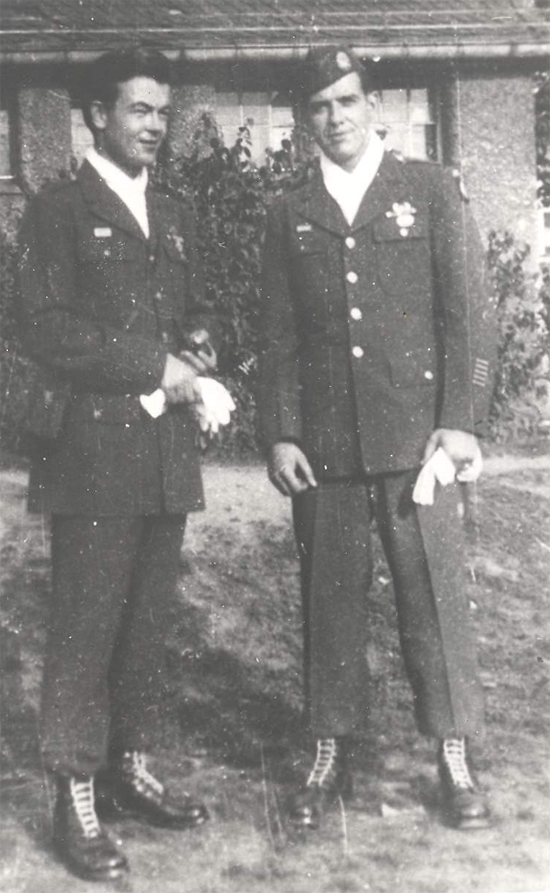

Mike Freeland in Columbus, Georgia. Picture taken in 1947, at the time Pfc Rudolph M. Freeland was attached to Headquarters Tennessee Military District (and an active member in the ERC). He now wears the SSI of his previous combat unit he served with in WW2 on his right shoulder.

Introduction:

More than half a century after it ended, World War 2 remains the most total and destructive conflict in human history. It involved all the major industrial countries, wrought unparalleled destruction, and it targeted civilians to an unprecedented extent.

The unprovoked attack of December 7, 1941 on Pearl Harbor united the nation under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and young men and women from all ranks of life enlisted in the Armed Forces in an all-out effort to defeat the foe!

I was just an ordinary farm boy who dropped out of High School to leave the familiar wooded hills and hollows of West Tennessee to go north looking for a job in a defense plant. I was born on May 14, 1924, the first child to Mason Noel Freeland and Wilby Lee Murphy. My birthplace was rural Buchanan, Henry County, Tennessee, in a remote community called “Blood River” (the river and community derive their name from battles fought between the Native-American Chickasaw Nation and the first white settlers alongside the river, legend has it that the stream ran red with blood following one fierce battle).

Induction and Basic Training:

I was eighteen when my military adventures began on a blue-cold early morning of March 10, 1943, in downtown Detroit, Michigan, with a stiff wind cutting down Woodward Avenue. I lined up in a public building the size of a football field with a bunch of total strangers, took a step forward, raised my right hand, took the oath, and became the ‘property’ of Uncle Sam! As a draftee, I was called up within the Selective Training & Service Act of 1940 and received ASN 36582565, designating a draftee of Sixth Corps Area, under jurisdiction of Second United States Army (Sixth Corps grouped the States of Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, with Area Headquarters in Chicago, Illinois -ed) .

In a few hours this bunch of draftees looking at each other suspiciously was moving by train to a frozen processing camp a full day north of Detroit, close to the Canadian border. My first hours in an Army barracks were something else, something I can’t find words to describe. How many ways can you find to say: “afraid – lonely – homesick – confused – angry – regretful – in pain …?” Home is not Detroit; Detroit is where the Draft Board found me working in a Ford Motor Company steel processing plant.

All the long first night when sleep won’t come I listen to the cadence of marching men and commands and curses … trucks coming and going. In the moonlight shadows I see the snow and the ice outside. Lights are out soon after dark and back on before daylight. Tonight in this crowded barracks, I’ve never felt more alone or afraid! The thing that scares me most is losing my freedom, my space, solitude, even time to think and read. Finally near daylight, just as I’m starting to drift off to sleep, bright lights crash on. “Everybody up! Mop up! Outside! Now! Move it!” I’m simply standing by my bunk, stunned, thinking … what? I’m supposed to do all this at once?

We go in a run, morning to night, identical close-cropped bald-headed idiots wearing new uniforms and shoes meant for someone else … there were endless hours of testing, physical, psychological, aptitude, and IQ, until our heads were stuffed with cotton and ached for a little rest … and don’t forget the propaganda films, “Why we fight?” and the delightful VD flicks. Our drained bodies continuously beg for sleep in the dark movie house, but broad shoulders is always there, prodding us awake with his swagger stick!

After an eternity (3 weeks) of abuse and confusion, shock treatment was over and one cold morning at Roll Call, my name is called along with about thirty other men. An hour later, we’re all packed, loaded on a train, – thank God – heading somewhere south for Basic Training.

A little after dark, two days later, we arrive, hungry and exhausted, at Ft. Knox, Kentucky (Armored Replacement Training Center & School -ed), an old Army Post south of Louisville. It is early April 1943. I was a High School dropout with no pre-conceived notions of military life with the exception of my limited contacts with soldiers from Cp. Tyson, located some 6 miles south of Paris, Tennessee (Barrage Balloon Training Center -ed) and from the movies. From Day ONE, I took to Army life, but more important Fort Knox became my college and in part filled in the life I always wanted – Boy Scouts, Golden Gloves, and summer camp all rolled into one … the other guys, who were to become my friends, were from all over the country: New York – New Jersey – Michigan – Florida – Georgia – California – Colorado, even Canada. I learned from every one. During Basic Training I was surprised to learn that I couldn’t make the Post Boxing Team or the Basketball Team. Not even close. I was surprised to learn that I couldn’t do one-handed chin-ups or push-ups and I never learned to read maps. On the positive side I made Expert Marksman on the M1 Garand Rifle with one of the highest scores in the Company and later was held over to teach marksmanship to the next class. I also scored well enough with armored vehicles to teach tank driving. Basic Training in Armor lasted 4 months (MOS 521, Private, Basic, allowed a soldier to be trained for any specialty occupation with the US Armed Forces -ed).

Basic was almost cut short for me and my M-4 medium Sherman tank crew one early fog-covered morning. I was driving wide open on the tank range – way too fast – on a curving trail up the side of a high hill. Without warning, one of the tank’s tracks locked up and we started slithering toward a drop-off, one breath from eternity. I didn’t have time to see my life flash before my eyes, no time for a prayer, but frozen in that moment I saw tree tops and the yawning valley below. At the last second, the tank’s right track turned loose and we veered left back onto the trail, sending showers of dirt and rocks into the valley. It was a close call.

General Henry S. Aurand (CG Sixth Service Command, Chicago, Illinois). The Sixth Service Command included the States of Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, and was under jurisdiction of the Second United States Army.

During Basic and the Advanced 8-week Combat Course that followed, I learned discipline. On the firing range, if you pull the pin on a hand grenade and freeze instead of throwing it – you’re dead. Same goes for the Infiltration Course, you’re crawling through stinking muck, barbed wire and smoke under living MG fire. You might be startled by a snake or a spider. Jump up and you’re dead. Dead is not smart, stupid can get you killed. Our acting Drill Sergeant “Tiny” (6-foot-5 tall and 300 pounds) had a favorite saying: “The more you learn over here, the more you stay alive over there. ” By the time spring ripened into a hot and dry summer, and summer turned into fall, our Company of raw recruits had gradually become soldiers – the US Army had done an amazing job once more – taking high school kids, store clerks, farmers, ranchers, cab drivers, citizens from all walks of life, making them into genuine soldiers. For me the most remarkable fact was finding those dark suspicious-looking strangers I first encountered in the Detroit Induction Center turn into some of the best friends I’d ever known. Friends I’d trust to guard my back in war and friends who could trust me to guard theirs.

1943 was the year of my Basic training – it was also the year newspapers headlined the meeting between President Franklin Roosevelt and PM Winston Churchill at Casablanca, French Morocco (Allied Conference 14 > 23 Jan 43 -ed). The year 1943 was when Dwight David Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces (SHAEF) for the coming invasion of Europe. Papers also carried endless stories of rubber and gasoline rationing. Sugar and butter were also on the list, and newspaper columnists promoted ‘Victory Gardens’, and complimented women for going to work in defense factories. There was a ‘war’ going on for sure, but it seemed so far away (and surely it would be over before we were needed). The best of all places to be in the summer of 1943, was stateside in Uncle Sam’s Army – especially at Ft. Knox (close enough to get home on a 3-day pass, catching the train in Louisville or Elizabethtown, reaching the Paris Depot, and either taking a cab ride or hitch-hiking to our farm).

Picture of M-4 Sherman tank crew taken in 1942 at Ft. Knox. 3 of the 5 crew members stand in front of their vehicle, tired, and well covered with dust, after field exercises and formation drills.

On a Monday morning, it was mid-October 1943, I was told that I was scheduled for more Basic Training. They sent me to Cp. Chaffee, Fort Smith, Arkansas (Armored Division Camp –ed). Well, it made sense to me. This was the Army, right? Take a tank driver, and make him a Medic. Good luck, pal.

… Joining the Medical Department:

Courses at the Medical School, Cp. Chaffee only covered 30 hours per week, spread over a period of 4 weeks (MOS 409, Medical Technician, basically provided for 12 months of Medical Training -ed) it was partly a re-run: close-order drills, calisthenics, and running. However, instead of breaking down the M1 and learning to read maps, Medics take partners and practise giving shots and taking blood from one another. Finger pricks hurt worse than going in the vein. You learn to be extremely careful and sensitive with the needle because you’re next. The golden rule is you better stick the other guy the way you want him to stick you. You just hope to God that your partner is not a drop-out from an auto mechanic’s or cook’s or baker’s school. My partner found himself working with a tank driver. I’ve seen 200-pound linebackers keel over and faint at the sight of a needle. Half of our training, led by young Medical Lieutenants, fresh out of school, is in the classrooms, half working with an Infantry Company in the field.

Road marches and maneuvers for a Medic are twice as hard, you’re always marching at the rear, taking care of blisters or heat exhaustion. Someone way up front of the Company yells: “Medic!” and you double-time there. All day. Blisters, ankle sprains, heat exhaustion – or worse, heat stroke. While the Platoon takes a break, the Medic works taking care of blisters, sprained ankles, and leg cramps …

Midway through the course one of the Doctors lectures while dissecting a cadaver. I watch more in horror than with fascination and keep thinking that only a while ago this chalk-white mass on the table was a whole living person capable of giving and receiving love – a warm breathing person with all the joy, the pain, the mystery that a life can hold. Where has life gone, leaving only this gray hulk called a cadaver? The Doctor goes about his business in a detached professional way slowly, thoughtfully examining, measuring, draining the blood, dissecting; he pauses for a while, then expertly cracks open the cranium, “Students, these bones form the enclosure – the brain pan.” The Doctor places the grayish clump of brain on the scales. “Any questions?” The response is a heavy silence.

Christmas will be here soon, Bing Crosby is back on the radio again singing “White Christmas” and this is the second in a row I’ve missed being home. Cp. Chaffee is too far, next to Oklahoma, and it would take a week just to get to Memphis. December 24, 1943 it snows a good four inches, but on Christmas morning the sun is shining. The weather is turning colder, and it is good to be inside and not out in the field. Less than a week to go before finals, and again we are reminded: the 2 students with the highest scores will stay here at the Hospital for Advanced Training. Everyone else ships out.

Students moan and bitch to one another when we see the nature of the tests. “Who do these Lieutenants think they’re teaching? This is not Yale, for Christ’s sake! This is supposed to be Medical Basic – not Medical School. They’re trying to show off what they know and were they’re from. Man, I’ve never seen this. This is mostly Greek to me.” The final test was a booger, lasting more than three hours. My brain turned to sawdust long before I finished writing.

When the final scores are posted no one could believe their eyes. At the top of the list, John Clubb, 96; my name is next with an identical score, we are the only two “A”s in the class! The next day John and I are called to the office and required to take another 3-hour test. We pass that one too, but instead of the promised training at the Hospital, we are immediately put on orders for transfer.

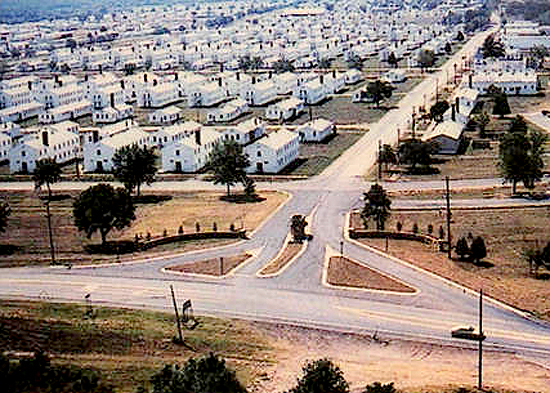

Partial view of Camp Chaffee, Fort Smith, Arkansas (Armored Division Camp). Built in 1941, this 75,000-acre military base trained thousands of American troops heading for overseas duty during World War 2. It had a troop capacity of 2,491 Officers and 41,330 EM.

FIRST Medical Assignment:

The war can wait. First Uncle Sam generously gives a leisurely tour to 2 Medical Privates starting at Ft. Sam Houston, a medical complex at San Antonio, Texas. We are unattached and on our own – we just have to show up for Roll Call and check the Bulletin Board regularly. We explore the city, see a couple of movies, drink Mexican beer and eat rattlesnake meat at the sidewalk cafés by the river. When money runs out, we write letters, listen to the radio and try to catch up on the news.

I’m in the Day Room, writing a letter and making notes in my Journal when John comes in. He looks excited: “Saddle up, soldier. We’re shipping out”.

Again we travel by train, this time northwest to Kansas City, then east to some place in Illinois, code named “Top Hat” (I don’t remember the real name of the place).We leave 80° sunny Ft. Sam Houston wearing summer khakis and step off the train in Illinois up to our ankles in snow and ice. I’m assignedto a Medical Detachment pertaining to the Hospital Train No. 22, made up of 55 Enlisted Men and 5 Commissioned Nurses (T/O 8-520 dated 1 Apr 42 indicates a personnel aggregate of 4 Commissioned Officers, 6 Nurses, and 33 Enlisted personnel -ed). We will move overseas, to Europe, and once there all personnel will live and work on the train, traveling as near the combat front as possible, picking up the wounded, treating them, and carrying them back to a regular Hospital.

I’ve been fascinated by trains for as long as I can remember. I grew up on a small isolated farm listening to the music of trains’ whistles drifting across the hills from Puryear (Henry County, Tennessee -ed), five miles away. I saw my first train when I was three. My prayers came true – I’ll soon sail the ocean, to live and work on a train …

Movement Overseas:

I still remember spending my 20th birthday on the Atlantic. After entraining for Cp. Kilmer (major transportation hub for US military personnel traveling to and from the ETO -ed), a Staging Area for the New York Port of Embarkation located between Edison and Piscataway, New Jersey, we sailed out of New York May 13, 1944 on the USS “Pittsburgh” one of the many new-built Liberty Ships, part of a convoy. Apart from sighting some flying fish, a school of sharks, groups of dolphins, and two giant spouting whales, we had nothing to do aboard ship, nothing but except sleep, read, watch, listen, and study the ever-changing face of the ocean, quiet as if resting, but at times, restless or angry, with color changes.

Rumors are that our Liberty Ship will land in Scotland. I manage to keep most of my food down, except when I have to visit the latrine. Some of the men are so seasick they scarcely leave their bunks. Then a nasty storm comes up which rocks our ship for hours, the ocean, our current world, turns violent. Monster waves crash across the deck, hurricane winds slam into the ship, shaking it with incredible force, while we cower in blackness below deck, hanging on for dear life to our bucking, pitching bunks, listening to eerie, strange crashing, clanging, banging, squeaks, the popping and hissing of our tormented ship. Nauseated and scared like hell, we are prisoners caged in stretcher-like bunks stacked six tiers high, and there is no way to escape the fury of the storm. God’s vengeance on our poor ship lets up almost as suddenly as it arrives, leaving as a reminder three glorious rainbows arched across the horizon.

Arrival in the United Kingdom:

Finally the ship reaches the United Kingdom. It is May 23, 1944, and soon thereafter, one late afternoon my unit, Hospital Train No. 22 is back on solid ground and aboard a miniature-sized British train. We leave Edinburgh, Scotland, and spend the next day riding through dark Scottish Highlands, alongside sparkling rivers and lakes, through dark hollows. We can see Scotland’s castles, mountains, plains, and the low hills of England. In Llandudno, Wales, after being sidetracked several more times, we have time to climb a hill overlooking the Irish Sea. At a village in Kent, the train pulls into a side track to wait for priority troop trains to pass, and it is there that we get our first glimpse of war – innocent children evacuated from fire-bombed London to the countryside. They’re offering apples for sale; we buy all the apples and give the kids K-Rations, chewing gum, and chocolate bars. We arrive late the next morning at our destination in Leicester, England, where we are immediately assigned to a US Army Hospital (most probably the 49th Station Hospital, at Diddington – there was also the 2d evacuation Hospital, which primarily treated USAAF patients -ed). After arriving we certainly expected more training, and John and I figured that at last we’d get that course in OR procedure we were promised but denied at Cp. Chaffee. Instead, our group landed on the run getting ready, along with everyone else, for the big invasion sure to come probably in days – even hours.

| Hospital Train No. 22 stations in the United Kingdom: | |

| Llandudno (Caernarvonshire) | 30 May 44 |

| Diddington (Cambridgeshire) | 30 May 44 > 15 June 44 |

| Lincoln (Lincolnshire) | 15 June 44 > 30 July 44 |

| Whitchurch (Shropshire) | 15 August 44 > 19 August 44 |

| Boughton (Nottinghamshire) | 2 October 44 > 14 October 44 |

Leicester and the Midlands is one vast American Training Base. Trains and trucks overloaded with troops and equipment move night and day, the sky is black with aircraft and their constant roar and vibration seem to shake the very ground. The first days of June bring nasty weather: rain and fog. Yet there’s no let up of activity – troops keep on marching and training, even the planes keep on flying. For the rest of my life I’ll remember that early morning of June 6, 1944, when we received the BBC news bulletin confirming that Allied Armies had begun landing on the northern coast of France. Then for several hours we waited, for more news. First reports were not good. “Allied Forces are meeting fierce resistance on the beaches. Progress is inch by inch against a hail of fire from Germans concealed and fortified in concrete bunkers. Allied Forces are suffering heavy losses.”

By mid-morning June 7, the wounded began arriving at the Hospital with firsthand news, direct from the battlefield. Some of these GIs could walk – most could not. Many were carried on stretchers.

It is now D+3, I’m bone-aching tired from the long hours, walking in my sleep, trying to stay awake. I’m in the Surgical Ward pulling a triple shift relieving Nurse Peterson (Chief Nurse, not her real name -ed), the prettiest and the most able person among our group of Nurses. This is the hardest part of the night, my whole body begs for sleep, yet it’s the best part, for there’s something about the coming of the dawn and a new day that is a special gift. Some of the soldiers are awake, smoking and quietly talking among themselves, telling their stories. I’m on my early morning rounds, carefully checking tourniquets and recording time, filling water pitchers, taking temperatures, and giving a few morphine shots. I look at these haggard doughboys and can’t believe they’re about my age, barely 20, some even younger. One bed chart reads – Singletree (native American), age 19, Oklahoma, Section Eight (battle fatigue). His hands shake so much I have to light his cigarette for him. “It’s OK.”I tell him. “It’s OK.”

“American Red Cross – Rainbow Corner” in London. This was the G.I.’s typical London rendez-vous place (corner of Shaftesbury Avenue and Windmill Street).

The soldier from Alabama wants someone to listen more than he wants the morphine. His eyes plead, try to understand. He says: “So many landing craft didn’t even make it to the beach; so many men drowned without even getting off a shot. On the beach we were sitting ducks taking machinegun fire, artillery, Jesus knows what else – and I am a Pfc leading the whole damn Rifle Company. Can you believe that? Just the 6 of us left and I’m left acting Company CO until I stepped on a mine and had to be evacuated. I’m wondering if anybody else made it.”

I hear the same stories more than once: so many men loaded down with packs, rifles and ammo were forced to jump into water over their heads. They never had a chance.

Glidermen and paratroops also tell their stories: “We were dropped as much as twenty miles from target. We landed in trees, on buildings, on top of Kraut artillery, in villages. Many of us landed in flooded fields between hedgerows and drowned or were shot before we could get out of our chutes. Lots of our guys were shot like target practice while hanging from trees…”

From down the hall someone calls, “Medic.” As I move away, the youngster from Alabama says: “It’s about a fair trade … I’ve lost my legs, but I’m going home – back to God’s country.”

The days and weeks of early June pass on. I volunteer for the night shift and become a night person. Life seems so much more drawn out and slowed down during the dark hours; but even with the long nights, there’s never enough time.

The Continent – France and Germany:

On June 26, 1944 we get some good news. Cherbourg (Cotentin Peninsula -ed) is liberated by the 79th Infantry Division. Any day now, our group could be assigned to a Hospital Train and move across the Channel into Northern France. First though, I have some personal business to attend to, I’m making application to transfer to the Airborne (I had felt like a tourist while stationed in Paris, traveling to Aachen, Germany, and enjoying fresh sheets and regular hot chow – I also wanted more than anything to test myself with the elite Airborne and wanted to know more about frontline combat). Near the end of July, our Hospital Train No. 22 rolls aboard a transport ship heading for Cherbourg. The Channel is rough with a hard wind kicking up waves. Finally the silent beaches of Normandy come in sight. I can still imagine the cries of men, the dense air filled with smoke, the crack of rifle fire, and the roar of cannon. On dawn of D-Day these waters turned red.

Picture of Mike Freeland with a fellow soldier, John Zimmerman. Somewhere in Belgium 1944.

From the beaches, our train moves on to St.-Lô along the dense hedgerows, and fields the enemy used for defense. All of this is real now, no longer a mystery or just a place on a map. There are shallow graves along the way marked by crude wooden crosses, and personal gear, rolls of barbed wire, burned-out hulks of American and German tanks, smashed jeeps and trucks, pieces of clothing… At St-Lô, where American troops finally broke through July 18, we find nothing but smoldering piles of stone and rubble, fragments of rock, and torn pieces of vehicles scattered about the countryside. Day-by-day the Hospital Train bumps on. We see convoys of abandoned enemy armor and trucks knocked out by bombers or simply out of gas. From time to time we watch German soldiers standing or sometimes sitting beside the tracks waving white cloths of surrender. Our train follows George Patton’s Third United States Army as it advances toward Paris, then on toward Germany. Nazi defense is crumbling all across France, Germany is “kaput.” The talk is to end the war in ‘44, and be home for Christmas!

At Aachen, the enemy stops running – now on their own soil, the Germans will fight to the death for their ‘Fatherland’. Bitter fighting rages street to street, house to house, room to room (the battle for Aachen lasted from 2 to 21 Oct 44 -ed). Here at Aachen, close enough to hear the artillery, we load casualties onto our train to take to a Hospital in Paris. The Hospital Train always runs with a full load. At Paris, we unload, turn around, and go for more …

New Assignment:

One late September morning, after the Hospital Train is unloaded, the First Sergeant hands me my transfer orders. My orders are to report to Ashwell Air Base (Hertfordshire) near Leicester for training and assignment to the 82d Airborne Division. I am finally transferred to the “All American” Division on October 18, 1944.

I am a 20-year old Private cut loose – alone – in Paris! Until then my only place and home was a Hospital Train, a place for my footlocker, my uniform, my books, and a place to eat and sleep, receive mail, and have someone to talk to … now, except for my orders, I’m on my own. My new orders don’t say when or how to report to Ashwell Air Base – so I’ll just take a few days off in Paris, I’m due a furlough, anyway.

Paris shows not one trace of war. After the Normandy beaches, St-Lô and all the other bombed-out, shattered towns and countryside we’ve been through, this is a surprise and a delight. And the trees – Paris is filled and surrounded by trees with leaves turning every shimmering color of September. I’d rather be here for a few days than anywhere else I can think of including home. I’m living a charmed life.

I made two important discoveries the first day: First, my orders can be used for billeting and cab fare. Second, I found a Service Club, the American Exchange – a kind of USO (United Service Organizations), where I can draw rations. Well, three discoveries. I learned I could survive alone in a large city. No longer did I feel, so “naked and alone. ”

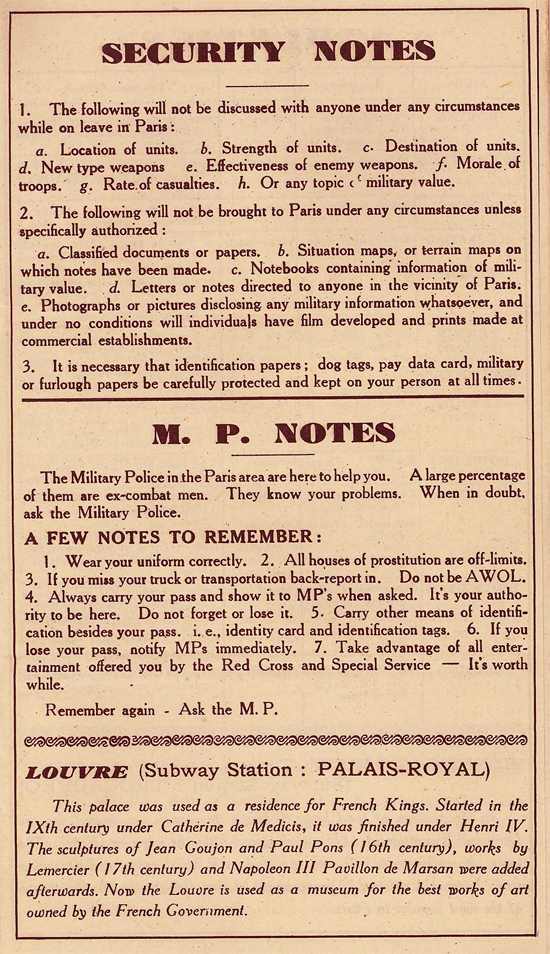

Reverse side of the “United States Army Paris Guide” (with security notes and directions) published by the Seine Section in March 1945, and distributed to United States Leave troops visiting Paris.

It is easy to slow down, rest and lose count of the days. I take a room on the second floor of a big Hotel on the Champs Elysées, a short walk from the Arc de Triomphe and less than a hour’s walk from the Eiffel Tower. My favorite place is a sidewalk café, two streets from the Hotel, shaded by a large chestnut tree. I sit for hours smoking my pipe, reading, sipping wine – just watching the world go by but mainly girl watching, watching sun-bronzed girls in short flowered skirts riding bicycles. Often I smile and wave; “Comment allez-vous?” the extent of my French vocabulary. Not one favors me with so much as a glance until I meet Monique several days later.

My days fall into a routine – early morning push-ups and sit-ups followed by a long run to get ready for Jump School, then breakfast at the Hotel, a pot of black coffee, fresh fruit and cheese with piles of crusty hard rolls. The rest of the day is for walking in the woods, a nap, then sitting by the river to watch the sun go down. Nights are for scoping out the bars and nightclubs. All seem the same, dimly lit caves, air thick with smoke, loud talk and laughter, louder music – painted dancing girls, old women, pimps, homosexuals, soldiers – the dark underbelly of Paris.

I found a place, a hang-out for students – or at least young people my age, sitting around reading books, arguing over pitchers of beer. For me the main attraction comes late in the evening, a blind piano player, an old black man who knocks out jazz and plays blues that sound like all the lonesome nights, days and places you’d ever known – all wrapped together. I feel the music to my soul and don’t need to understand one word.

One night I leave the hangout early to try out the subway. Why I don’t know, unless the drinks I had made me adventurous. Anyway, big mistake. To be lost on the Paris subway, especially late at night, is an experience from hell.

I don’t know enough French to ask directions and if any passenger speaks English, he doesn’t let on. Plus I don’t exactly win friends by singing snatches of “Yankee Soldier” and asking, “Anybody here speak American?” Finally, I am rescued by a sweet angel wearing a Nun’s black habit. She puts me off at the right station and points me toward the Eiffel Tower. Still I’m lost, completely turned around. I don’t know the left bank of the right (Seine River banks –ed). I don’t think I can find my way with a map and compass. I’m frustrated, tired and thirsty; my head’s spinning, so I lean against a stone wall and rest for a few moments. I am alone, not another person can I see – yet I can feel someone watching me. I see no one. I listen. Not a sound except distant frogs and peepers on the river. Then I smell perfume and am startled when a woman steps from the shadows.

She wears a dark blouse open at the neck, a short skirt, and high heels. She steps into full moonlight without speaking. I look for a moment straight into her piercing eyes. She breaks the silence, “Have you a cigarette for Monique?” The voice is soft but confident, the dialect broken English. I stand entranced by her level gaze, saying nothing. “Soldier”, she repeats, “have you a cigarette for Monique?” Again I say nothing. Under the spell of this woman’s dark gaze, I am speechless. Then I offer her a Chesterfield and light it with my Zippo. I finally find my voice, “Can I buy you a drink?” For the first time she looks away and smiles, “Toute suite, Chéri.”I take her reply as affirmative. “You lead the way. I’m lost.”

She leads us to a Club downtown on a street I remember called “Pig Alley.” I’m enchanted by this woman, this woman of Paris. She’s smart and sophisticated and I’ve always preferred older women. I love the way she makes me feel – important and self-confident. She tells me how to choose a wine – “It has nothing to do with price, Joe, simply pick a wine you enjoy.” We talk about books, Wolfe’s “Look Homeward Angel” and Hemingway. She met Ernest Hemingway once at a party at the Ritz Hotel where he lives and writes dispatches, supposedly from the frontlines. I remember sampling an awful lot of wine talking. I remember we walked in a garden near the river. I rested with my head in her lap and watched the last stars disappear from the washed purple sky.

The last thing I remember was her cool hands on my face and her hushed voice crooning, “Sleep, sleep.” Crows and jaybirds fighting in the nearby trees – or the hot sun on my face – awaken me. Can this awful pain be my head? Where am I? What time is it? I glance at my wrist. I’ve lost my watch!

“Monique.” “Monique, love, where are you? ”I feel like I’m going to be sick, my head’s splitting. “Monique, Where are you?” She is gone! Gone, too, is my wallet, my watch, my ring, my Zippo, my cigarettes. All gone. Thank God, she overlooked the manila envelope in my inside pocket.

I walk to the Hotel to pick up my duffel bag and check out. After a long cold shower, two aspirins, coffee and rolls, I decide that I will live. Again I use my orders to hail a cab to the airfield. With luck I’ll catch a plane for London – soon I hope. For me, Paris has lost most of its glitter and all of its romance.

I find one positive: life is a learning experience, after all. So get on with it, get back to work. I just hope some chickenshit Company clerk somewhere hasn’t checked a roster: “Where’s Freeland?” he’ll ask. “He’s supposed to be in this class.”

I find a C-47 heading for London, and I’m the only passenger, except for a Major wearing a Third United States Army shoulder insignia. The moment I climb aboard, it feels as if I’m back in a combat zone. After crossing the Channel through patches of fog and clouds, the white chalk cliffs of Dover make their appearance. Approaching London, I’m startled to see entire blocks leveled by bombs; only burned-out hulks of buildings are left standing among smoking piles of rubble and isolated walls. This is my second night in London. I spent a restless first night on an upper floor of a Piccadilly Circus hotel. When the buzz bombs fall and sirens begin to wail, I remain where I am, but no more. It’s one thing to be brave, something else to be stupid. For my second night I’ll go to the subway, the safest place I can find.

The London I find is cold, gray, and gloomy, smoke and fog burn my eyes. Make it hard to see. The city is crowded and the sooner I can get out of here, the better. These are Churchill’s people. They won’t ever give up. Not in a million years. In Winston Churchill’s words; “We’ll never give up – we’ll fight the enemy on the beaches and in the fields and in the streets and in our houses, but we won’t give up.” I spend the night sitting crunched in a dry corner, waiting, thinking, watching my brothers and sisters for the night. Families have settled down with blankets, pots, thermos, chess sets, cards as though this were the most normal thing in the world. It’s just one more night like all the others. God only knows how they find the courage and strength to keep on. When daylight comes, they’ll go back to work, picking up what may be left, some back to houses and neighborhoods that aren’t there anymore. They will stand in long lines that wind around blocks holding their ration cards, waiting to buy whatever is offered. More often than not, there’s nothing left to buy.

Time has no meaning here; each minute stands alone, broad and drawn-out as a day. Each hour is a lifetime. Sirens wail, and then become quiet. We listen. Then, there’s almost blessed relief when the bombs fall. “Down near the docks,” they reckon. “The waiting – the awful waiting – is the worst part,” they say. That’s the way it must be with death. The waiting, not knowing – the dead. It’s quiet again. For a moment or so I can almost forget where I am then a baby cries. The people, huddled in blankets with hungry, sleep-starved eyes, wait for the morning light. A girl with incredible blue eyes, wearing a military uniform, stands near me; “Whatcha writing, Yank?” she wants to know. “My Journal,” I respond, “It’s about British grit,” wondering if she wants to talk – wondering if she could tell me what it’s like to be here, night after night, four long years, listening to the sirens. Waiting for the bombs – savage fire bombs that light up the sky and turn it red. Could she tell me what London was like before the war? Before the lights went out? Before the Americans came?

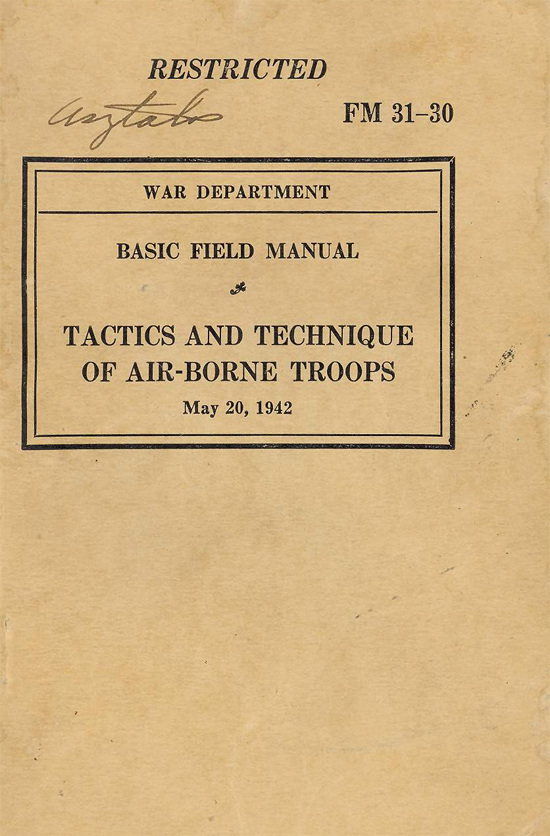

Basic Field Manual FM 31-30 “Tactics and Technique of Air-Borne Troops”, WD publication, Washington, dated May 20, 1942

“God bless you, Yank, and God bless your President Roosevelt,” she says and moves away. We sit alone with our thoughts and wait for the bombs. We wait for morning to come.

Before leaving London, I stop briefly at the USO on Piccadilly Circus for donuts and a free coke and to write a letter home. This USO must be the largest in the world, and the busiest, even at this early hour, it is hard to get a table. I remember catching rides from the USO to Ashwell, climbing in the back of a truck and a couple of jeeps and crashing from lack of sleep over the past three nights.

I remember arriving at Ahswell Air Base late in the afternoon, hungry, dogtired, and still groggy, but the good news is that I have permission to join the class in progress and make my first jump tomorrow.

Jump Training Course

The purpose of the course was to produce trainees capable of:

- withstanding the physical shocks encountered in parachute landings

- jumping from a plane without hesitation and without danger to fellow jumpers

- manipulating the parachute during descent so as to land in a suitable area

- landing without injury

The various phases of the Jump Training Course included the following instruction outlines and allotted time (ref. FM 31-30 Tactics and Technique of Air-Borne Troops, dated May 20, 1942):

| Suspended Harness | 6 hours | |

| Door Practice | 6 hours | |

| Landing Trainer | 6 hours | |

| Tumbling and Platform | 6 hours | |

| Trampoline and Stall Bars | 6 hours | |

| Trainasium | 10 hours | |

| Lectures | 4 hours | |

| Qualification Tests | 8 hours |

First Jump:

Next early morning, with hardly time for comprehensive jump training, I’m sitting near the open door in a vibrating C-47 just like the one I flew in from Paris. I’m sweating like hell. The hard straps of my heavy, tight-fitting chute cut into my shoulders, pulling me forward into a crouch. It’s hard to breathe. The big plane thunders down the field and lifts into the air and keeps on climbing. Shafts of sunlight break through the early morning haze, and up ahead blue skies show through puffy white clouds. I’m sitting, jammed in between a line of other jumpers – called a stick – wondering what’s next? The Jumpmaster, a lean-muscled redhaired NCO called ‘Smitty’ walks up and down the aisle checking each man’s chute. “Okay, men,” he yells, “This is a perfect day for jumping!”- “You’ve done this before. You know what to do!” But the trouble is, I don’t know what to do! I’ve never done this before! “What do I do?” I ask the trooper on my right. The soldier looks surprised. “What?”- “I’ve just joined, what do I do?” I imagine he’s thinking, how did this guy get on the plane? “Here, watch me,” he says. “This is called a Static Line, when we stand up, hook onto that steel cable.” He then points to the ceiling, “Make sure it’s over your left shoulder like this, and not under your arm. You go out the door with the line under your arm, it could tear it off or slam you against the side of the plane with enough force to kill you … when you stand in the door, look straight out – don’t look down. OK?” I hang on to every word, “Thanks,” I say. “Anything else I need to know?” “Yeah, listen pal,” he says, “They tell you when landing keep your feet wide apart. Don’t do that. You’re liable to land uneven on one foot and break an ankle. I say, keep your feet together – stronger that way and when you hit the ground, try to stay relaxed and start rolling to reduce the shock…”

The Jumpmaster yells, “We’ll soon be leveling off and make a pass over our DZ.” He moves close to the open door bracing against the door’s frame, the hard driving wind distorting his face. “Jump-off point coming up guys, get ready. Stand up and hook up!” Each man stands up and snaps his static line onto the overhead steel cable. Checks it briefly. I follow, listen for the sharp reassuring click of steel against steel, give two strong yanks to make sure it’s secure, and check whether the static line is over my shoulder and not under my arm.

“Check equipment.” followed by “Sound off for equipment check!” Smitty yells. “Number One, okay!” “Number Two, okay!” “Number Three, okay!” On down the line as each man checks the equipment of the man in front. I feel my heart pounding, I tell myself, “Just stand in the door, don’t look down.” My mouth is dry and tight. “Stand in the door!” Smitty barks. The soldier in front of me shuffles to the door, crouches, waiting for the Jumpmaster’s signal. Then he’s gone, tumbling over and over in the plane’s prop blast. Now it’s my turn to stand in the door. I feel the strong wind, cold against my hot face, hear the roar of the plane, I look straight out toward the horizon. Off to my right beyond the trees, almost obscured by a milky fog is Ashwell, with Leicester across the river. I breathe deeply – taste sweet fresh air – washed clean by last night’s brief shower, and truly appreciate the gift of life as never before. “Go!” Smitty yells while slapping my leg. I bolt straight out from the plane, spinning head-over-heels tossed by the powerful force of the prop blast, yet without the slightest sensation of falling. I start counting, “Thousand and one. Thousand and two. Thousa… POW! The chute opens and grabs me – hard! I look up, what a sight, my beautiful gently swaying canopy, holding me in the air, protecting me. I’ve never seen such a beautiful sight. I’m gently floating, still there’s no feeling of falling, what a quiet and peaceful world. I’d like to stay up for a while but my ride is ending, all too soon. Now the sensation of falling is there, fast. The earth rushes out to meet me. I remember, keep both feet together. I smack into the ground, remembering to tumble in order to distribute the shock and then lie still for a moment, breathing hard… I stand up a little unsteady on my feet, collapse my chute, feeling proud of myself. Thankful. Just to be back on good old Mother Earth brings me joy. The scent of fall was in the air: decaying grass, clovers, and wild onions. The good earth.

Troopers are landing near, laughing, and folding their chutes, calling to one another, “Hey! That first step was a bitch!” One of the guys walks toward me. “Mac, looks like you just had a close call. Look, your steel pot’s gone, and your liner’s got a big hole in the back.” I feel my head, no steel helmet and the back of my liner is ripped apart. I take it off and study the big gaping hole and think how close the steel connector link had come to my brain when it exploded from the parachute. Too close. Suddenly, I don’t feel quite so feisty, not well at all, but lucky! I’ve got to be the luckiest man alive – this airborne business could be like one strike and you’re out. The soldier looks at me again, “Mac, you better, damn sure, count your blessings. Just one gnat’s hair closer, you’d be dead meat!” Most of the jumpers in the area are spilling the wind out of their chutes and rolling them up; some are already walking back to the truck, but one guy is stretched out on his back, not moving. “What’s wrong with that guy?” I ask the GI who called me ‘Mac’. “Fella hurt his back upon landing, don’t know how much. Looks like he’s gonna be taking a ride in the ambulance.” We loaded into the truck with Sgt. Lepenski and headed back toward camp. I’ve never felt such contentment, more at ease with myself and the world, and being thankful for the gift of life. “One jump down, four to go!” (to qualify for rating as a “Parachutist” the student was required to make 5 satisfactory jumps from varying altitudes in at least 2 of which he participated in mass jumps of 12 men each -ed).

After finishing four more jumps to qualify as a Parachutist, there’s little to report, except that I’ve learned that jumping can be addictive. The adrenaline rush starts even before you strap on your parachute and climb on the plane, and builds up gradually as you become airborne. The biggest rush comes from diving out the door tumbling in space waiting for your chute to open and grab, but it’s over too soon – floating down to earth is a quiet serene sensation, and I can’t wait to face my moments of terror and jump again.

I treasure those days at Ashwell, the early morning runs by the foggy river, the feel of chilled early fall days that warm up on the long hard hills. The most special day became November 12, 1944, the day I finished Jump School and received my wings!

Several of us are at the “Bull’s Head” pub. This is supposed to be the big night, initiation party, pin on our silver jump wings – go crazy. There’s a long standing tradition at the “Bull’s Head” of paratroopers, after drinking a while, smashing their glasses against the wall, and jumping through a second floor window, yelling “Geronimo.” But not this class, not tonight. Our hearts are just not to it. At this very moment the 82d Airborne is tied down in Holland, suffering terrible casualties. Any day now this class will go its separate ways. For the 4 Medics, Lombardo – Mississippi – Lance – and Freeland, the destination is Sissone, France, home base for the “All American” and the “Screaming Eagles” (101st A/B Division -ed). “You are the survivors,” Smith stands up, waves his glass, “Toast.” “The best of us are here,” the tall soldier called Preacher says. “All together now, sing a Hell of a Way to Die.” We don’t all know the words, but we are loud and we know the chorus – “Gory, Gory, Hallelujah, Gory, Gory, Hallelujah, I ain’t gonna jump no more!”Preacher raises his glass again and repeats; “The best of us are here. Chug-a-lug.” We chug-a-lug, slam our glasses on the table. “I really like this place,” I say to whoever is listening. No one is listening, I stand up, on the table, call for attention, hold up my glass to make a toast, but give up. Doesn’t matter. Now Smitty stands up, moves around the table like he’s lost. “Where are we?” Where are the rest of the gang?” No one answers, no one is listening! “Are we all here?” Smitty yells again. Twelve of us left base together, now we’re down to six: Lance, Smitty, Preacher, Lombardo, Mississippi, me, or seven if you count Gavin. Okay, seven. Gavin’s the sober one sprawled near the fireplace. Tonight Gavin wears shiny new silver jump wings on his collar with as much pride as anyone else – maybe more. He finished 5 jumps today. We can trace Gavin’s history back to St-Lô (France). Wounded, half-starved, he’d been deserted by the Germans, got picked up by some 82d MPs who nursed him back to health and he now belongs to the “All American. His full name is James M. Gavin after our Commanding General. Gavin’s a good dog, and smart, smart enough to dislike Officers. Perhaps they remind him of the Germans who left him to die.

My head is spinning. I must be way ahead of everyone else. My eyes are fixed on the pub’s smoke-stained walls supporting rough hewn wooden beams crisscrossing the ceiling. The long bar is trimmed at the corners with worn leather and dull copper. “Old Graybeard” behind the bar looks ancient enough to have served honeymead to Roman soldiers. Between drawing pitchers of beer, he buffs the bar to a hard shine and from time to time sings out in a stunning baritone; “Let’s drink up mates – Life is short and war is long” Preacher orders another round, “Life is short and war is long!” We bring a toast to our “Brave brothers fighting this very night in Holland.” I toast the brave men and women I met in blacked-out London, “God bless, you Yanks,” they said. “God bless your President Roosevelt.” We’re back at our table. It’s getting later and louder. “Life is short and war is long. Drink up mates, closing time. ” Together we sing out; “Life is short and war is long.” Then we laugh like hell. Hollow laughter. The town clock chimes two. I remember being with Lum, Gavin, and a few others staggering down the middle of the street singing a song we made up: – Going to Sissone City – sung to the tune of “Going to Kansas City.” (1943 song featured in the musical play “Oklahoma” -ed).

Oh, Babe, I’m going to Sissone City

Just to sing my song.

Going to Sissone City

But I won’t be long,

Oh, Babe, I’m going …

I remember a feeling of sadness knowing that our class is splitting up and sorrow for leaving home again. I remember being very sick in the MP’s jeep more than once before we reached the airfield at Ashwell.

While at Sissone, Aisne, France, (former WW1 French camp and barracks, where the 82d arrived on 1 Dec 44 -ed) we wait and listen for the word to move out. Listening to every rumor – the 82d will jump into Berlin. The 82d is being called back to the ZI and will make tours selling War Bonds. I heard straight from the old man himself that we’re going to the Pacific. The wildest talk could start in your own tent any morning and by night it would be all over the camp. Spinning rumors is an Army pastime.

December 17, 1944:

(After the long battle in Holland (17 Sep > 13 Nov 44), the 82d and the 101st Airborne Divisions, both pertaining to Ridgway’s XVIII A/B Corps lay in camp near Reims, France, resting and refitting, and training, while preparing for any new airborne operation. On December 16, the XVIII Airborne Corps constituted the Allies’ only strategic reserve in Western Europe. Less than thirty-six hours after the outbreak of the enemy counteroffensive, First and Ninth United States Armies turned to SHAEF asking for the immediate release of its two Airborne Divisions in order to reinforce the VIII Corps area in the Ardennes. Being equipped for airborne warfare, the two divisions had little organic transportation, and had therefore to depend on outside means. The Oise Section (ComZ) immediately came to the rescue, collecting enough 10-ton open trucks and trailers, and securing a large number of 2 ½-ton ‘jimmies’ for transportation (with attached elements of the 666th Quartermaster Truck Company). The 82d was selected to lead a first motor convoy into Belgium, and because of late arrival of Major General Matthew B. Ridgway (CG XVIII A/B Corps), “Slim” Jim Gavin (CG 82d A/B Div) assumed the role of acting Corps Commander. Initial movement orders were received at 2100 hours directing the Division to move by motor convoy and concentrate in the vicinity of Bastogne, Belgium –ed).

A KP from the Officers’ Mess brought the wildest rumor yet. Krauts by the thousands were breaking through Allied lines in the Belgian Ardennes. The reaction in our tent was, “Yeah, sure. But I like the one about getting home by the first of the new year better.” However, this last rumor, a whopper no one could believe, turned out to be rock-solid. Crack panzer units, paratroopers, and SS troops had broken through American lines in a wide front near Aachen. Armed Forces radio reported what appeared to be the largest German Counteroffensive of the war, gaining momentum by the hour.

December 1944 – on the move to Belgium:

I’m tired, worked all night packing personal and medical equipment. Trucks are lined up. We should be pulling out any minute now. Goodbye, Sissone. Goodbye, mud floor tents. Goodbye and good riddance. Wrote several letters home. Ate chocolate D-Ration and smoked my last English cigar. At last we’re loaded and moving out.

Hardly more than twelve hours after receiving our orders to move out, the convoy is on the road. We’re heading toward Belgium or wherever we will meet the Germans. You could have been in our truck for only five minutes and know the replacements from the combat-hardened veterans. The rookies joke and put on brave faces fooling no one. I’m sitting next to Mississippi; even in the hard chilling cold his face is flushed. “I’m transferring to the Infantry, by God,” he says. “I need to be in the killing business, not the healing business.” He looks quickly side to side as though to challenge anyone who might disagree. “Whatcha think, Freeland?” He pokes me in my side for emphasis. “Ain’t that right?” “You got that right,” I say, hoping to dodge another elbow in my ribs and more spit in my face. “Ain’t that right?” he repeats… I’m jammed hard against the truck’s tailgate, between Mississippi and Lombardo. There’s nothing to do except shiver from fear and cold. I have a strong feeling this day will mark a day I’ll recall as a milepost in my life. All during the night sketchy radio bulletins report Germans sweeping through US lines advancing with great speed toward Paris.

Everyone keeps asking; “What happened? Where did the damn Krauts come from?” It seemed as if the war was all over but the shouting. Why didn’t our intelligence notice the enemy build-up? I settle back and try to sleep but sleep won’t come. I’m tired and cold even though I’m wearing long johns, extra socks, gloves, and an overcoat. Even worse than the cold, my stomach is cramping and my bladder is stretched as far as it will go. Pretty soon I’ll have to make my way to the end of the truck just like the others and somehow hang on with one hand. “Do you think if you fell off and broke your ass, you’d be eligible for the Purple Heart?” someone waiting in line grunted. “Yeah, if you get lucky, you could break your neck and get the Medal of Honor,” came the answer. “I’ve got an idea how to stop all wars! Instead of all the ‘Why We Fight’ training films, show miserable bastards like us with the G.I. runs (diarrhea -ed) trying to take a crap out of a bouncing truck running a hundred miles an hour. Ain’t no way anybody goes to war.” For a while, the bantering is led by the replacements. The convoy slows for nothing except long stretches of muddy roads and detours around blown-out bridges. We pass through many deserted Belgian villages. From the sound of artillery and the muzzle flashes of big guns it is apparent the advancing enemy forces are near.

It is near the end of the day, about an hour before dark, when our convoy stops on a hill overlooking a long open valley. We’ve been on the road at least fourteen solid hours, except for maybe a total of thirty minutes when we unloaded to dig out of mud holes. “Where are we?” The rain has stopped and turned into fresh snow falling in soft clumps. In the distance we hear somber booms like thunder before a summer storm. “Artillery,” one of the vets says…

At 0900 hours, on the morning of December 18, the “All American” Division had originally started for Bastogne, Belgium, but was diverted short of its destination and ordered to set up at Werbomont in order to hold and defend the North flank of the German penetration. The advance party of the 82d arrived in the village of Werbomont at 1730 hours and immediately opened a temporary Division CP. The bulk of the unit moved into the area during the same night without any enemy opposition. By the morning of December 20, the Division had successfully set up a defensive screen north, east, south, and west of Werbomont. Fortunately this move was unknown to German intelligence. To say the overall situation was thoroughly confused, wouldn’t be too strong a statement.

(The 82d A/B Division, still awaiting replacements and much re-supply at its base camps in the Suippes-Sissone area, moved 150 miles with its first combat elements going into position in less than 24 hours and the entire Division closing in a new combat area in less than 40 hours from the time of receiving the initial alert. — James M. Gavin, Major General, US Army, Commanding. -ed)

Battle of the Bulge:

In combat you know so little about what’s really going on. My sparse Journal doesn’t help a lot. There are, however, memories and pictures burned into my mind fresh and real as yesterday.

My first trip to the front with my medic partner, Mississippi, for example, stands out clearest of all. I know exactly where he was sitting on the cellar steps to my right. I can hear his quavering voice, “Freeland, are they coming? Are they coming to get me?” We’re in a dank cellar with a Rifle Squad. This is the first hour under fire for both of us.

Getting to the outpost was challenge enough for anyone. Entering an open field, we first smelled the stench of burning hair and flesh before we saw the smoldering tank and charred bodies of the German crew nearby. Farther along the trail in the woods, we saw bodies of GIs half buried in the mud and snow. A shell explodes nearby sending a shower of dirt from the ceiling. Mississippi wails; “What’s that?” “It’s a German 88”, someone says. “No, it’s a Screaming Meemie.” You can tell from the way it sounds. They’re high velocity. Throw fragments in all directions. Mississippi wails again; “Are they coming? Oh, God, are they coming to get me?”Another screamer hits so close, we feel the vibration, sending more dirt showers from the ceiling. This is not the Mississippi I know, not the one tough soldier I wanted above all for a combat buddy. Earlier driving up in our jeep, he was strangely quiet but I didn’t think anything about it. Now he starts wailing once more, “Oh, God. Mama, where are you? I’m afraid. Come and get me, Mama.” Mississippi sits huddled on the steps, sobbing, “Mama.”

Mike Freeland and Bob Quinn on leave in Belgium. This picture was taken after the Battle of the Bulge during R & E in the rear.

The sergeant puts down his rifle and walked toward us, motions, “Get him out of here. He’s psycho. Take him to the Aid Station. Get him back!” In a little while the shelling lets up. I get Mississippi into the jeep and light out for the Aid Station.

Sometime later I write three words in my Journal to describe the experience: “Friend goes berserk.” This is the wrong word. Mississippi was never violent nor in a rage; the correct word is “trauma”, a painful emotional experience, or shock, often producing a lasting psychic or behavioral effect and, sometimes, a neurosis. WW1 doughboys suffered from “shell shock” (term introduced in 1915 -ed). Medical Basic Training didn’t touch the subject – whatever it’s called.

The many battles, that came to be known as “The Battle of the Bulge”, lasted from December 16, 1944, until January 28, 1945. Estimated US losses amounted to over 80,000. My Journal offers mostly brief notes, short paragraphs at most. Yet a line, even a few words, can spur a memory. “Nightmare and horror of war. Bloody history written before my eyes. At the front, time is measured by staying alive one moment at a time. It’s how long it’s been since your last mail from home. How long it’s been since your last shower, shave, hot chow, a cigarette or a hot coffee.”

There simply is no other place in the world to compare to the stark loneliness and misery of a foxhole. For soldiers in holes up to their knees in icy water in the frozen snow-covered Ardennes forests, time stands still. Gangrene (local death of soft tissues due to loss of blood supply -ed), frostbite (partial freezing of some body part -ed) and trenchfoot (painful foot disorder resembling frostbite caused by exposure to cold and wet -ed) are a threat dreaded as much as death. In foxholes, hungry, haggard GIs try to stay awake and alert all night to keep from freezing to death and then somehow be ready to fight when day comes. The mind often goes before the body. At first when you get near the front, you’re shocked and saddened by the sight of dead animals, such as horses, cows, and birds. Medical treatment in the field is rendered even more difficult because of terrain and weather conditions. We have to care and evacuate our patients under the most adverse conditions; and not only is the casualty rate extremely high but the hilly and wooded terrain present additional difficulties for evacuation.

Farther on are wrecked, burning vehicles, scattered rifles, steel helmets, haversacks, individual gear. Then you see the dead, American and German. You’ve seen so much, by the time you reach the Aid Station that you hardly notice the frozen, snow-covered bodies stacked outside near the door like so many ricks of cross-ties. Don’t look, you tell yourself. Don’t think. You could go crazy, a condition noted on our medical charts as “schizophrenia” (psychotic disorder and disintegration of personality -ed). Or is it“shell shock?” (post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from combat experience -ed). An early warning signal for shell shock, I believe, is when you start feeling guilty for being alive, that somehow it’s not right when so many of your buddies are dead and you’re still living!

Bulge, winter 1944. Long advance in knee-deep snow through mine and booby-trapped infested woods and fields …

(The 82d Airborne Division fought, stopped, and held against the best units German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, could pit against it, protecting the North shoulder of the Allied line, preventing the German break-through from turning north to Liège, Belgium, and providing a safe area through which trapped Allied units could withdraw from the break-through area. This it did despite the fact that its lines at times were stretched more than 25,000 yards. Then, turning to the offense, the Division set the pace for other units, forcing the enemy back through his famed Siegfried Line. — James M. Gavin, Major General, US Army, Commanding -ed)

By early February 1945, our Division maintained and improved its defensive positions, while reconnoitering and patroling the enemy defenses. On February 2, the “All American” advanced and breached the Siegfried Line against intense opposition. Positions were consolidated and numerous counterattacks repulsed, but our troopers held the line.

“Long advance in knee-deep snow through mine, and booby trap-infested woods. The Siegfried Line is constructed of huge concrete bunkers protected by barbed wire fences, minefields, and large embedded concrete blocks. We’re in the mountains not far from Aachen where my previous outfit, Hospital Train No. 22, once made its regular runs from the front to Paris.”(notes from personal Journal -ed).

Troopers advance through thickets and woods in snow in some places up to their waists. One man goes out front breaking the way until he’s exhausted, then the next man takes his place. It’s bone-weary, slow-going, dangerous work. Krauts lie in wait in concealed bunkers then hit us in a murderous crossfire from machineguns and rifles. We suffer heavy casualties every step on the way. I can’t help but wonder how long my luck will hold out. When I think of all the frozen bodies I’ve seen in ditches and stacked outside Aid Stations and when I think of all the GIs who’ve died on a litter strapped to my jeep because of shock, loss of blood, the freezing temperature, a tourniquet that didn’t hold, or some other reason, I feel responsible. I wonder “Why not me? Why am I still alive?” Losing a buddy is the hardest of all. It’s like losing a brother. But men keep on coming: fresh-faced, green replacements who learn fast or die soon. Compared to these innocents, I feel like a true veteran.

We are now in the woods in the immediate vicinity of the Siegfried Line where resistance is gradually crumbling meeting mortar, small arms, and sniper fire. You wouldn’t recognize the bearded vacant-eyed men, old men dressed in filthy, blood-stained uniforms, slogging through snow, muck and mud, not even close to a military manner, but slumped over, dragging one foot after the other. They carry their rifles like a heavy burden. On my left in a small cleared field I see one of our men, obviously badly wounded but alive. Sofar, I’ve answered every “Medic!” call, but not today. Krauts target medical personnel first, kill the aidman and you cripple the whole unit. My armband and the Red Cross marker on my jeep are only inviting targets for the invisible snipers. I have no weapon. The thoughts rush through my head. I call the Platoon Leader: “We’ve got a man down out there!” The Lieutenant stares at me with glazed eyes and plods on. “Will you send someone?” I ask. “I’ll do it.” The speaker must have been one of the new noncoms, a Corporal. You could tell from his cleaner uniform, his fresh face, his eagerness to help, as he dashed into the field. When I heard the rifle crack, I knew it was the sniper, I knew the Corporal was hit even before he spun and staggered on toward me. He threw down rifle and helmet, and tried to step forward, holding his throat with both hands, hands that couldn’t hold back or stop spurting streams of bright red blood. There was nothing else to do except to get him into one of the jeeps and evacuate him to the Aid Station. Fast. “Just hold this pad to your neck as tight as you can.” I tell him. “Hold on, man…”

He tries to speak but only gurgles, blowing bloody foam. His eyes beg “Do something.” I drive as fast as I can, praying for a miracle, telling him over and over again; “Hang on. Just hang on. I promise you, we’ll make it. I promise you we’ll make it.” But when I said it, I knew I was lying. I’m sure the Corporal did, too. I wanted to tell him I wish it had been me instead of you, but that too would have been a lie. Otherwise why didn’t I go into that field? That’s the question I expect to live with for the rest of my life.

The Corporal slowly bled white, fell over against me and died long before we reached the Aid Station. I was covered with his blood. I never knew his name or his hometown. Nothing. But I’ll never forget his face, those wide pleading eyes begging: “Do something!” I’ll never forget, right or wrong, I’ll always feel responsible – and guilty …

Picture of M-4 Medium (Sherman) Tank with mounted infantry, taken in Germany, it illustrates an armored vehicle of the 3d Armored Division. Typical crew of a medium-type tank crew is composed of 5 members: commander, gunner, bow gunner (assistant driver & radio operator), tank driver, cannoneer (loader & assistant gunner).

Days pass and I fall into a sort of dull routine, transporting wounded from the frontlines to the Aid Station. Victor Lombardo from New York alternates with Ira Covington from Georgia and Joe Gilotti from Michigan as my medic partners. This is gorgeous country painted in sparkling white, but all of it is deadly with booby traps and mines.

For the past twenty-four hours all the talk at the Company and the Aid Station has been about what happened at Malmédy. The few survivors who faked death told what happened. At Malmédy (Baugnez crossroads area -ed) 86 captured American soldiers were massacred in cold blood by German SS troops; at Honsfeld, another 19 unarmed US servicemen were killed; at Büllingen another 50 GIs were shot; and at Wereth 11 unarmed PWs were murdered! Among the casualties were quite a few medical personnel as well belonging to the following units: 200th Field Artillery Battalion – 546th Ambulance Company (Motorized) – 575th Ambulance Company (Motorized) – 333d Field Artillery Battalion.

(Malmédy (Baugnez) Massacre, 17 Dec 44 > the main units involved were Headquarters Battery and B Battery, of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion (7th Armd Div) – it was not until January 13, 1945, that American forces recaptured the area around Baugnez. First United States Army Headquarters selected the 3060th Quartermaster Graves Registration Service Company to recover, process, and identify the remains of the US casualties –ed).

I search for words to describe my own experience but words are not strong enough to tell all that needs to be told. How can mere words written on paper convey images, shock, pain, and death found along what General Gavin called the ‘bloody trail’? There’s no way. And so I let my mind become numb. But I cannot escape. I will never forget.

Between February 5 – 6, 1945, all 82d Airborne elements are pulled off the line after being first relieved by the 99th Infantry Division. We all move to the Vielsalm area to reorganize and refit. Spread over February 19 > 21, we are then definitively relieved by the 9th Infantry Division and assemble in the Walheim area from where we commence the move to our base camps in the vicinity of Reims, France. All units, less organic transportation, move by rail, and close in at Sissone by February 25. The unit left some 4,000 men killed or wounded but no one wants to think about that. Nor does one dare think of all those left a while ago in Sicily, Italy, Normandy, and Holland. You dare not think how many more good men will die before we reach Berlin – or meet the Soviets – whichever comes first. And the Pacific, some say. The Pacific Theater’s next when this job is done!

Off the Line and back to France:

Sissone hasn’t changed that much except the yellow sucking mud has turned to crusty ice. The cold wind now blows harder through the flat gray village and camp. It still is Sissone, mud city. I’m sitting on my canvas cot reading my mail and smoking one of Lombardo’s cigars. My ration of cognac is finished leaving a mellow feeling of relaxation. I’m still warm from a long hot shower this morning and from the heat coming from the wood stove now glowing red. I will think of war no more, not for a little while at least. 7 troopers share this tent: Bob Quinn (Michigan); John Zimmerman (Tennessee); Giorgio Terezzi (New Jersey); Joe Gilotti (Michigan); and 3 recruits from the States (Ft. Benning Jump School) whose names I don’t know. Three young kids talking tough, asking stupid questions: “What’s the front like? Were you scared?” Stuff like that. When no one answers, they stop asking. Gusty winds rattle the sides of the tent. I think of the time so few weeks ago – no, a lifetime ago – winds pushing and popping the top of our truck rushing toward Belgium. I was one of the several green replacements gripped with fear and wonder. Now I’m one of the lucky survivors – a veteran.

“So, tell me what it’s like, the fighting I mean,” the kid asks again. Again I say nothing, let the war rest for a while. But my silent mind has its way. I could say, you’ll just have to find out for yourself, that’s all. If I told you, it’s the “silence” , you wouldn’t know what the hell I’m talking about – the silence, it’s the stillness – the stillness that gets to you when the battle is over.

I still remember, that night in the London Subway – the awful silence waiting for the bomb to fall. Silence so heavy you can feel it when the battle is done. Silence and smoke and sadness come as one and you look around to see what’s left, the dead and the dying …

Entering Germany:

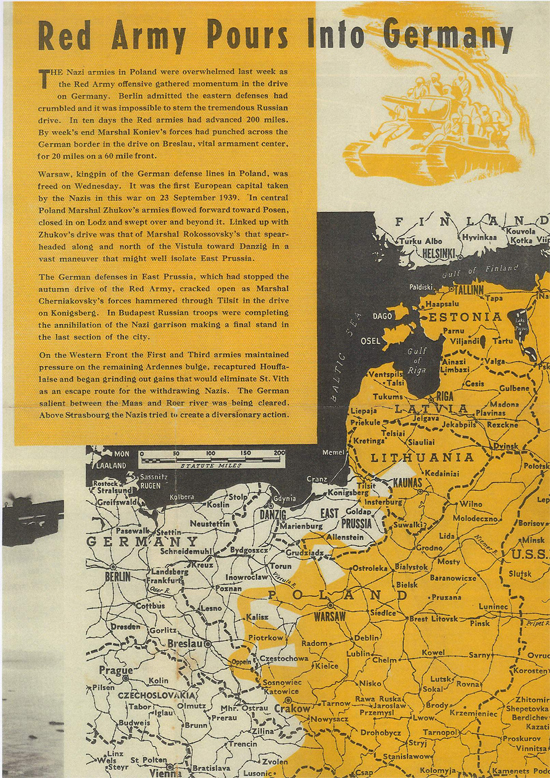

Cover page of PWD/SHAEF psychological warfare leaflet No. 16, dated 26 April 1945 dropped over Germany announcing that Berlin is now surrounded by the Red Army.

In less than two weeks our Division is back in battle. Reports say that the First and Third United States Armies are advancing all across a wide front encircling thousands of enemy troops, artillery, and tanks. The 82d continues slowly toward the Ruhr delayed only by minefields, artillery, and bad roads. The roads are either slick with ice, choked with traffic, or a quagmire of mud. Hitler’s desperate gamble is finished. The Bulge is over. The “All American” presses on toward the Rhine River, toward Cologne, hard on the heels of the retreating German Army. Again the talk is of home and of beating the Soviets to Berlin.

Raw fear is my constant companion. I’ve become calloused to the stench of rotting flesh, the sight of blood and death, entrails spilling out of bodies or hanging on branches in the trees with other body parts mixed with pieces of clothing – perhaps scraps of letters and family pictures. One GI, a buddy from Tennessee and a jeep driver, ran over a 500-lb Kraut bomb and became nothing more than a shower of blood, flesh, and bits of bone. I’ve learned to ignore the stacks of snow covered corpses with staring sightless eyes and gaping mouths. Look away, I tell myself, or go crazy.

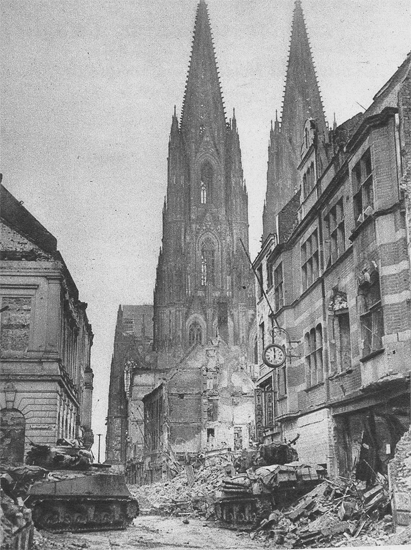

Cologne March 1945, US medium tanks advance cautiously in the rubble around the Cathedral.

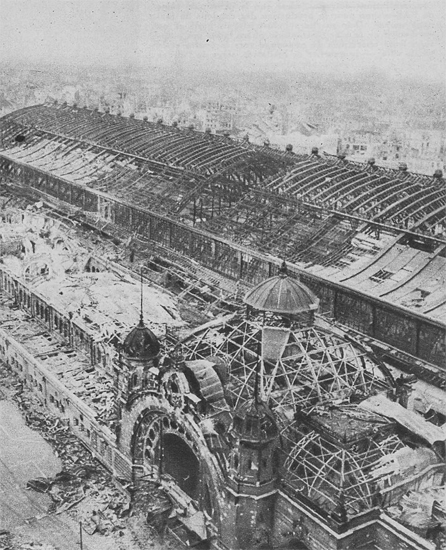

Savage fighting continues with heavy losses for both Allies and Germans. The fighting in the Ruhr Pocket is now over. Our unit, the 307th Airborne Medical Company, continues to care for the wounded, the dying, and the dead. Late one afternoon when Sgt. Covington, Lance, Lombardo, Gilotti, and I were on duty in the Aid Station, 4 German Officers show up and ask to surrender. Slicked-up in shiny boots, pressed uniforms with chests full of ribbons, they reek of alcohol and insolence but seem relieved to become our prisoners. This was a big deal at the time, but it was only the beginning. A few weeks later, an entire German Army surrenders to our Division. (German 21st Army Group on 2 May 1945 –ed). At the time our troopers are spread out for miles north and south of Cologne, along the Rhine. The war is grinding to an end. Soon the fog of war will be replaced by a more dense fog of peace for the 82d, with an assignment to take over and care for DP camps holding former slave laborers, thousands of Russians, Poles, French, Belgian, Dutch, Czechoslovaks, and Italians, an occupational role we aren’t trained to handle and don’t want … My unit is encamped in Cologne (captured by the 3d Armored Division which moved into the city March 5, 1945 -ed); a city of rubble and weeds with one remarkable exception, the ancient Gothic Cathedral (Kölner Dom built 1248-1880 –ed) which stands in the center of the ruins, almost without a scratch, it looks like the only cultural exhibit to retain any of its former glory. Despite fourteen hits by Allied bombers, the exterior is relatively intact except for the roof, and its large stained glass windows, all of which have either been removed or broken. American forces took the city, Germany’s third largest, and the biggest yet to fall to Allied troops in less than three days.

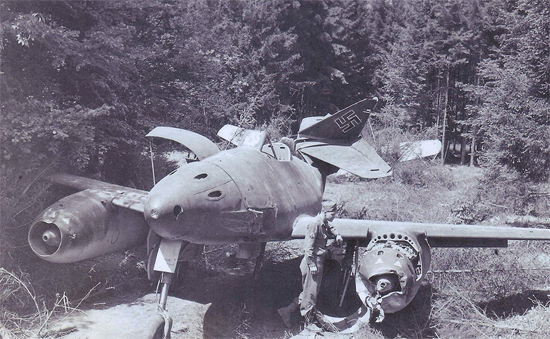

Abandoned German Messerschmitt Me 262 jet plane, discovered by the advancing American forces somewhere in Germany.

The smell and promise of early spring is in the air, a warm breeze blows from the river. Melting snow reveals patches of green grass and tulips blooming in the fields beyond the city. I drive this way every day from the 307th Airborne Medical Company to the dispensary. As far as I can see everything is flattened and in the midst of all this destruction, the Cathedral, with its two tall towers stands watching over a landscape of bombed buildings, blown bridges, and roofless rubble. It stands erect like a miracle as though having been protected by an invisible shield. From daylight until dusk, German women, children, and a few old men are working patiently in the rubble chipping mortar from bricks, stacking them in neat rows. The grown-ups work bent over, never looking up, but the kids look up, smile, sometimes wave and ask for chocolate. Except for sniping and occasional artillery fire from across the Rhine River, this area is quiet.

April 1945, smoldering German “Panther” tank in front of Cologne’s ancient Gothic Cathedral.

Late one afternoon, Lombardo, Lance and I are together riding jeep patrol near the edge of town. I’m driving and thinking ‘chow-time’. Suddenly, Lum says: “Stop the jeep. I want to see this.” He points to an old man and woman, hard to tell how old, maybe sixty, with white hair, stooped over, working a small garden near the road. Between the garden and the house stand fruit trees and a small grape arbor. “C’mon,” Lum says. “Let’s get out, OK?” “What the hell for?” Lance asks, but follows Lombardo and me toward the garden.

The day is still warm. I can smell the rich soil and decaying manure from the garden. We slowly walk toward the old folks. The man is bent over a digging fork looking at the ground. The woman is shaking but looks directly at us. Her eyes are blue, sad, haunted, but she speaks with a firm and confident voice. “Guten Abend meine Herren. Wilkommen in unserem Heim.””Haben Sie Schnapps und Cognac?” Lance asks, getting right to the point. “Nein, wir haben kein Alkohol. Möchten Sie Tee?” “I think tea would be nice.” Lance grins and we follow them inside. The old woman quickly brews tea and serves it. The man is quiet at first and then speaks for the first time. “Meine Herren, wir sind keine Nazis.”The ‘Frau’ serves more tea. Somewhere a clock chimes. Then Lance surprises me; “Listen, goddammit. I know goddamn well that you Krauts got something to drink and I want it tout damn suite. You verstanden?” I look at him, “C’mon, Lance, let’s knock it off.” Then he does something that surprises me even more. He pulls out a .45 pistol. “I want schnapps, cognac now! Understand?” “Jesus Christ, Lance. What’s got into you?” Lum asks. “C’mon, Lance,” I say; “Put that damn gun away. Let’s get out of here! We’re scaring these old people to death and we’re going to be in trouble.” Lances refuses to budge, “Im’ staying!” “Bitte, meine Herren, wir wollen keine Schwierigkeiten. Wir sind alte Leute! Ich hole den Schnapps!” ”Hot damn. I knew they were lying. I knew they had it.” Lance gloats and tucks the .45 into his belt. From the cellar the old man brings two dusty bottles. The woman brings four nice crystal goblets from a cabinet. The drink is a good rich, mellow, cognac. I’m feeling a delicious warm glow – at peace with myself and the world. The big clock near the fireplace slowly counts time dusk falls. Lombardo produces a pack of ‘Old Gold’, offers them around. The woman smiles, shakes her head, no. The old man takes a cigarette, “Danke.””Schnapps, godammitt,” Lance growls. From the fading light at the window, I see his flushed face. “Don’t give me no bullshit,” he says. “Schnapps tout damn suite, OK?” The old man fetches two more bottles from the cellar. Lombardo pours us another round. Our hosts decline. “OK, guys drink up,” Lombardo says. “Drink up. We’re outta here!” I didn’t see the gun come out. I just heard Pow! Pow! It was Lance’s .45. One shot went through the ceiling, one through the floor! “Lance, are you outta of your mind?” I can’t believe what I’m seeing. “Gimme that damn gun!””Back the hell off, Freeland! I’m gonna kill these damn Nazis!” The old people are holding one another. She’s sobbing, “Bitte, bitte, bitte…” “You rotten Nazi bastards robbed and killed my people,” Lance grates, “Now it’s payback time!” “Lance,” Lombardo yells, “What the bloody hell you’re talkin’ about? Those old people ain’t hurt nobody – c’mon now, buddy, let’s take our drinks and go, OK?” “Yeah,” I add, “I’m tired and hungry. Plus, we’re gonna be in big trouble if we don’t get outta here. Let’s go get some hot chow.” Lance is swaying on his feet, waving his gun, still undecided. Suddenly he hands the gun to me. “Here.” It’s late when we leave. I’m mentally exhausted. We leave the old man collapsed in a chair holding his chest with both hands, the old woman kneeling at his side with her fingers laced in prayer softly moaning over and over, “Bitte, bitte, bitte.” Lance sits in the back of the jeep in a stupor, still babbling, “Damn Nazis killed my people. Damn Nazis killed my people.” Lombardo stares straight ahead; “The guy just flipped his lid. Drunk and crazy is what I think.” Lombardo continues: “I know, I’m embarrassed. That’s all. That old couple was no more Nazi than we are. Even if they were – for Christ’s sake – we’re not in the execution business. Right?” “Right.” I reply. We pass the Cathedral; its twin towers stand tall, dark, and silent against the moonlight as they have stood for more than 600 years. I drive on to the dispensary.

Victims of nazi persecution and horror, thousands of Displaced Persons are waiting for help, food, and some place to go…