Veteran’s Testimony – Charles K. McGrane 280th Station Hospital

The following story was received from Pfc. Charles K McGrane (ASN: 32746400) His story is reproduced here with his kind permission and the authors are truly thankful for his willingness to share his personal reminiscences with their readers.

Portrait photograph of Pfc. Charles K. McGrane (ASN: 32746400).

Introduction:

When we turned 18, we registered for the draft. I got my notice late in 1942 to report for induction in February of 1943. We gathered at the train station in Albany and boarded a train for New York City. I have some recollection of Grand Central Station in New York where we changed to the Long Island Railroad for Camp Upton on Long Island. We were issued uniforms and packed all our civilian clothes to send home. It was very cold and there were long waits in formation. We were tested to see where we would be sent. I was assigned to the Medical Department as a clerk. That was not my idea of soldiering, but the Army wasn’t interested in my opinion!

Training:

I was told that I could apply for a transfer to the Air Force after basic training. My group went to Camp Pickett in Virginia. Basic was not too bad. There was a night march once with full packs and gear. I got tired going up a long hill but was determined not be the first one to fall out. After a while it got easier and then it wasn’t hard anymore. It was a lesson that I never forgot.

Group photo of Charles and members of his Camp Pickett unit. He is the young soldier on the left of the front row.

Once I ended up in the hospital with pneumonia. I went on sick call and the aid station medics told me to go back and get all my gear. I dragged myself back with everything I owned and climbed into a truck. The hospital at Camp Pickett was crowded. They put me on a cot in a big ward. Every once in a while someone woke me to take some medicine. After a couple of days I got better. As soon as I was able to get up they put me on KP (kitchen police) and I washed dishes.

Luckily, I didn’t lose too much time and I finished basic with my company. Then we were sent to Camp Ellis in Illinois.

Photo showing a Ward Tent erected on the grounds of Camp Ellis. This was used as a training aid for members of the 280th until it moved to Camp Livingston in Louisiana.

Assignment:

We were assigned to permanent units at Camp Ellis. I joined the 280th Station Hospital and stayed with them for about a year and a half. From Camp Ellis, we went down to Camp Livingston, Louisiana. Some of us worked in the camp hospital. There was also an increase in field training.

Photograph showing Charles McGrane and Dave Muir. It was taken at Camp Livingston. The original caption read: This is Dave Muir and I. Dave is the good looking guy.

Dave and I took the test for Aviation Cadet training and did very well. But before the transfer went through, the 280th was alerted for movement overseas. That was the end of my transfer to the Air Force.

Camp Livingston had towers with cargo-nets that trained us to climb down from the deck of a ship into landing craft. This would prove useful later. Our Commanding Officer, Colonel Zellhoffer, wanted us all to learn to swim. There was a large swimming pool that we used, but not everyone learned. Of course it wouldn’t have done much good crossing the Atlantic in December. One exercise had us climbing out of a trench and crawling across a field under machine gun fire. The tracer bullets were a couple of feet off the ground. Getting up out of the trench was the scary part.

We were given a 10-day furlough before we shipped out. I went back to Albany on the train and then took a bus out to Geneva. There wasn’t a bus to Romulus, but I was offered a ride on a freight train, no charge. It stopped in Romulus for me. I spent a few days there before heading back to Louisiana. My aunt asked me to go to school once and talk to the kids. They were very interested in anything about the war.

My father was the postmaster in Romulus. I helped him sort some mail that had been run over by a train. There was a system that caught a mail bag suspended on a pole. A hook from the moving train would catch the bag and at the same time they would throw a mail bag off. One of the those bags bounced under the train wheels and some of the letters were mangled. He also showed me a revolver that the postal authorities had given him because he handled a lot of money for the Seneca Ordnance Depot. He kept the weapon in the post office safe.

Movement Overseas:

We left Louisiana in December, 1943 and went by train to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. Our next move was on a ferryboat up the Hudson River. Then we moved in long lines through Pier 81. There was a short gangplank from the pier into a ship. The line climbed up several decks and then out into the cold night. Someone saw “Queen Mary” painted over on one of the lifeboats.

We sailed late in the afternoon of December 23rd. The ship had to catch the tide in order to clear the top of the Holland Tunnel. Ferry boats were whistling at us and everyone waved. Sunset reflected off the windows of the buildings; it was beautiful.

The Queen Mary in her wartime colors. The New York end of the Holland Tunnel is shown beyond the ship.

Photo courtesy of this website.

We hit a winter storm on Christmas. I was one of the fortunates who didn’t get sick and I would escape the crowded cabin to get out on deck. That ship was known to roll violently in heavy seas. It would roll through an arc of 60 degrees: 30 degrees to port and then back to starboard. I would be looking up at giant black waves and then back down at them. We would pitch and toss. When the propellers came out of the water it would seem that we were tearing ourselves to pieces. That storm is the most powerful thing that I had ever seen.

United Kingdom:

We arrived in Scotland on a bright morning and anchored in the Clyde. There was a show going on with all the ships. A small British aircraft carrier was near us. Their Swordfish torpedo bombers were practicing takeoffs and landings while the ship was anchored. Our turn to debark came late in the day. Lighters would pull alongside to take us ashore. The Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth (sister ships) were taking turns bringing us over to England. They alternated and each made a round trip every two weeks. Churchill said that they made the D-Day invasion possible.

Oddly enough I never saw the outside of our ship until we left it. Trains were waiting to take us south. We passed Glasgow in the distance. It was a long night. We passed many towns and villages, all of them blacked out. Then we reached a place near Cambridge that had tents and cots to sleep on. There was an RAF field right next to us where Lancaster bombers took off over our heads. All this was still very strange.

Photograph showing 280th Station Hospital staff at Shortgrove in Newport, Essex. The soldier standing in the center of the first row is Colonel Zellhoffer, our Commanding Officer.

Then we moved down to the village of Newport and set up on the Shortgrove Estate. Our hospital would use long ward tents for the patients and smaller tents for everything else, but first we had to use shelter halves. These were the most basic shelter used during the war. They consisted of two shelter halves snapped together and spread over tent poles. Then they were tied to wooden tent pegs. About all they were good for was protection from snow or rain.

The 364th Engineer General Service Regiment (Cld) started construction of the hospital on 17 December in 1943. They were building walkways and concrete platforms for our tents. This unit consisted of African-American soldiers. Our Army was still segregated then. They worked very hard and the work came together quickly. I have a strong memory of them marching down the hill, singing at the end of the day.

Altogether the hospital consisted of one hundred ninety pyramidal tents, eighty-three ward tents, twenty storage tents, sixteen small wall tents, and two large wall tents. The small wall tents and some pyramidal tents were used as latrines in the ward blocks.

Water, electricity, and telephone service were provided from civil sources and were adequate for all hospital needs. Where necessary, transformers were installed to reduce the 220 volt current to 110 volts.

Then we were up off the ground and into the pyramidal tents. Seven of us shared each tent. We had a little pot-belly stove to enjoy in the evening. Our tent was issued one steel helmet of coal each day during cold weather. It would last for most of the night.

The Pharmacy group that I was assigned to. They each had a specialty. I was their clerk.

There was a lot of training going on then. We were still practicing for our real job, treating battle casualties. There were many American airfields in this part of England. They were all very busy in 1944. The bombers would form up early in the morning and gain altitude over our heads. The roar of several thousand engines would seem to shake the ground. Some time later the fighters would take off to protect the bombers.

The 4th Fighter Group flew from an airfield a couple of miles from our hospital. They were the first unit to receive the P-51 Mustang. This plane had enough range to stay with the bombers all the way to the furthest targets. They had the speed, maneuverability and firepower to match anything that the Luftwaffe had. This Group was formed originally from members of the RAF Eagle Squadrons, Americans who were fighting with the British before our country got into the war.

Debden’s fighters would take off just in time to relieve the shorter range groups. I found out recently that a class mate was assigned to the 334th Fighter Squadron at Debden. I asked him if he always flew the same plane. He said yes, then corrected by saying that he had loaned it to someone once and it was shot down. Another question was how he got along with Colonel Blakeslee, the Group commander. He said that he got chewed out once. The way that happened was my friend was coming back low on fuel and put down at an emergency field near the coast. It had a very long runway, and rather than taxi a half a mile, he held it off until he was closer to the service area, then landed. He tried that at Debden and Blakeslee asked him where the hell he learned to land an airplane.

Debden was very generous with their hot water and we went over there frequently to take showers. They also let us watch the gun camera films that were developed after each mission. The pilots would cheer or groan as they watched. These guys were the best of the best. They led every other group in German planes destroyed.

One of the better off-duty activities was bike riding. One of our group bought an English bike. These were much easier to ride than the American bicycle of those times. He was generous with it and I took advantage to explore the countryside. It was beautiful. Once I happened upon a practice field where a Sterling bomber was dropping bags of white colored something, maybe chalk or flour.

Another highlight was the Liberty Truck. It would make a run into Cambridge where we could walk on real pavement and see the English people, simple pleasures. There was a Red Cross Club in Cambridge, I think it was the “Brooklyn Club” or something like that. They had a phonograph with a record that I played over and over again, Dinah Shore singing The Memphis Blues. Years later I thought about writing and telling her about that. I wish I had.

London was not far from where we were. If we could get a 48-hour pass, that’s where we headed. It was a magic town for Americans in 1944. They loved us. We could jump on a bus or use the Underground, get off almost anywhere and have a great time. A soldier in my pay grade had very little money, but it didn’t matter. I remember once I needed a haircut. A barber gave me one and then shaved me. I didn’t need to shave very often in those days, but he did it anyway. He wouldn’t take any money. Hunger was something else. Soldiers were always hungry. There were old guys selling fish-and-chips. They would maybe have a pushcart under an overpass where they would fry up a very inexpensive meal and wrap it in newspaper. It was delicious.

The Red Cross had a canteen just off Piccadilly Circus, the “Rainbow Corner”. They served donuts and coffee. I don’t think they charged anything, or maybe just a little. We were enjoying that once when someone pointed to a lady cleaning the tables. I was told that it was Fred Astaire’s sister. He and Adele were dance partners in their younger days, then she married into the British aristocracy and they split. She became Lady Cavendish and he went on to the movies. I’m not really sure of the details, but I did see her.

The Red Cross also ran a place where you could sleep. Very plain, double-deck bunks and it cost hardly anything. I was asleep there once when a drunken GI opened the door and started peeing on the floor. Somebody threw a shoe at him. Many years later a friend that we met in our travels started telling us about that incident. I said “George, I was there.” Small world isn’t it? George was a B-26 crew chief and he has some great stories.

Some wartime pictures of London taken by one of my friends

The last stop was “Dirty Dicks”. This was a pub close to the Liverpool Street Station where we got the train back to Newport. It was a dark sinister place where cobwebs hung from the ceiling. It was full of noise and smoke. Years later, I passed it with my wife and dragged her in. It was lots brighter now and also cleaner and they served meals. While we were eating, the proprietor stopped and asked us how everything was. I had to tell him that I’d been here before he was born.

Two 280th Station Hospital personnel standing in front of “Dirty Dicks”, a popular stop for members of the Hospital during their furloughs!

Then it was D-Day and our war got serious. Casualties from Normandy began to arrive.

American patients lie on litter awaiting treatment at the 280th Station Hospital. These troops were received in the days which directly followed the D-Day Landings.

We received thousands of casualties from France. We were ready for them. The first train load were moved from the train and into the hospital wards in 105 minutes.

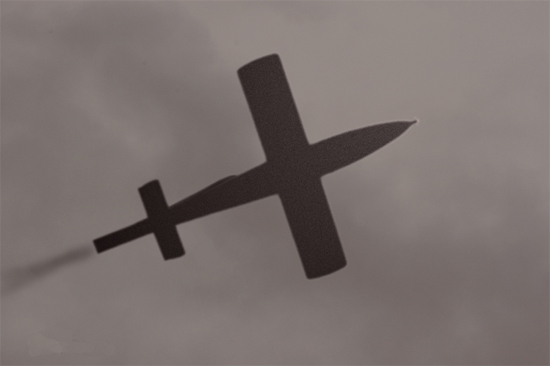

A V1 flying bomb passed over our hospital shortly after D-Day. Its engine cut out and it went into a steep dive. We heard later that it killed some Americans.

France:

Then we were needed in France. We struck the tents, packed up and loaded on trucks that transported us to the Channel where a ship was waiting for us. It was an old P & O liner, the Llangibby Castle. This was a rather small ship but we had it all to ourselves. There were hammocks to sleep in. The crossing didn’t take long. We anchored off Utah Beach. There was a cargo net to climb down into landing craft. Most of the beach had been cleared but there was still evidence of the fighting. I remember seeing a ship that had gone down by the stern. Most of it was still above water.

Then we gathered all our gear and started inland. The town of Ste-Mère-Eglise was eight or ten miles from the beach. We bedded down in the church yard. I have seen it since. It’s now a tourist attraction, nothing like I remembered. The field that was our first home is now a parking lot. We were there about a week. One of the farmers had straw that made a pretty good bed. We set up a field kitchen and that brightened things up. There was a tent with a movie projector which showed Frank Sinatra in a musical. People found apple cider and Calvados. It was during our time there that I turned 21. There was an arrangement for us to vote in the coming election. I am pretty sure that I voted for President Roosevelt.

A convoy of 2 1/2 Ton “Deuce and a Half” GMC Trucks transport personnel and equipment of the 280th Station Hospital to its new location in Cherbourg.

The Army had a plan to bring units directly to France on the big ocean liners. They would come into Cherbourg and unload, then take casualties on the return trip. It didn’t happen that way, the harbor had been ruined by German demolitions, but that was the plan. Our hospital would be the collection point in Cherbourg.We were to take over and operate a French hospital in Cherbourg. The Germans had used it when they were there. Another American medical unit was there before us. It needed cleaning up and this was done as we began receiving patients.

We settled into a routine. I was assigned to the Admissions office where we collected information about our patients. Then they were examined, treated or admitted for further care. We kept a couple of ambulances ready to go when needed. I went along on one call from the port section where there was an injury. It was a Polish person who had been pressed into service by the Germans. He wore a German uniform. There was a lot of that. Europe was all messed up in 1944. There were a lot of displaced persons.

A young Sergeant came in one morning with some German prisoners. They were being treated when he came over and we started talking. The usual conversation started with “Where are you from”. He said something about upstate New York, Willard. That was a surprise. Willard is very close to Romulus. I told him my dad was the postmaster in Romulus. He said, “Charlie McGrane? He’s my uncle”. Bill Pearson was one of my cousins, and we didn’t remember ever meeting before.

Cherbourg was an interesting place in 1944. I met a sailor who had been looking for his brother. But the unit that he belonged to had moved out. The sailor had a package that he couldn’t deliver, three dozen fresh eggs. “Did I want them?” Of course, I did! All we ever got were the powdered version, edible, but not very good.

The Germans broke through our lines on the 16th of December 1944. It didn’t seem possible that this could happen, but it did. There were even Germans dressed in American uniforms that made attacks on some of our positions. This caused trouble and it was blown all out of proportion. A group that I was with was challenged by a Lieutenant who pointed an M3 sub machine gun at us. This was a very crude weapon but very dangerous. One of our group spoke English with a heavy accent which aroused his suspicion.

Photograph showing the battle damage to a street in Cherbourg.

We got a phone call on Christmas Eve that a ship had been torpedoed near Cherbourg. We were told that we might get some casualties. A convoy coming from England was attacked by a submarine that fired a torpedo into the side of the Léopoldville. This was a Belgian ship with a crew of Africans from the Belgian Congo. The ship lost power and started to drift into waters that hadn’t been cleared of mines. The convoy commander ordered the Léopoldville to drop its anchor. Then the Léopoldville Captain gave the order to abandon ship. The crew took off in the lifeboats. Our soldiers were told that the ship was in no danger of sinking. There was a second announcement that it would be towed into Cherbourg. That was also wrong. When tugs finally arrived they couldn’t move the ship. There was no way to lift the anchor.

Some of the soldiers jumped onto the deck of a British destroyer that came alongside, but this was dangerous. Those who timed the jump wrong went down between the ships and were crushed when the hulls came together. Most waited for a rescue that never came. They were still waiting when the ship sank.

The SS “Léopoldville” transporting 2,235 American servicemen, from the 262nd and 264th Infantry Regiments (66th Infantry Division) across the English Channel, was torpedoed by the German submarine U-486, just five and one half miles from Cherbourg. The date was 24 December 1944. The death toll was 763 confirmed deaths. The “Léopoldville” disaster was one of the worst tragedies to befall a US Army unit, as a result of an enemy submarine attack.

Illustration showing SS “Léopoldville” prior to its sinking on Christmas Eve, 1944.

Photograph courtesy of wrecksite.eu.

The ones that were rescued were in various stages of hypothermia. Many died in our hospital, one as I was trying to verify his identity, he was too cold to answer.

The Army was running short of riflemen in the line outfits and began accepting volunteers. I applied.

Pfc. Charles K. McGrane (ASN: 32746400). This photograph was taken during Charles’ time in Germany, 1945.

This concludes Charles’ story about his time with the 280th Station Hospital. The author corresponded with Charles about his service after the 280th, but Charles decided that it was not relevant to include it in his Testimony for this website. Here is a brief explanation from him:

Maybe I will write some more, maybe not. The 280th Station Hospital was my family for about a year and a half and I still identify with it.

For completeness, however, a brief description of Charles’ service with the United States Army after his time with the 280th Station Hospital follows. He was sent back to England where he underwent Infantry Basic Training and was finally entered into the replacement stream. Having been transferred to the 9th Infantry Division, Pfc. Chas. K. McGrane ended the war in Germany, and having no desire to remain in the military, he was Honorably Discharged on 4 March 1946. Charles re-enlisted in the New York National Guard (27th Infantry Division, 105th Infantry Regiment) on 15 May 1953, around the time of the Korean War, where he remained until 21 May 1959 and obtained the rank of Master Sergeant. He now lives happily in New York with his wife.

undefined

Unless otherwise stated, all of the images and texts in this Testimony are courtesy of Pfc. Charles K. McGrane (ASN: 32746400). The authors are truly thankful for his sharing of this story in the hope that the memory of the 280th Station Hospital will not be lost ….