Veteran’s Testimony – John D. Little Second Platoon, 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

Portrait of Private John D. Little, ASN 38508482, Second Platoon, 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company. This photo may have been taken in Belgium (Liège ?), some time late 1944.

Introduction:

My name is John D. LITTLE. I was born 9 February, 1924 in Kingston, Arkansas. Kingston is in Madison County which is part of the Ozark Mountain Region of Arkansas, U.S.A. My Parents were John Clyde Little and Wilma Parker. I had five siblings; 3 sisters, Dorothy Mae, Sarah Alice, Wilma Marie and 2 brothers, William (Bill) Parker and Gerald (Jerry) Henry. We lived on the Little Homestead up Sweden Creek until 1930 when we moved to Mayfield, Idaho, to join my Grandparents on their farm during the Depression. About 10 years later in 1940 we moved back to Kingston when I was about 16.

During those years between 1940 and when I was drafted on 21 January 1943, I worked at any job to make money. I worked the wheat harvest in Kansas, I traveled to Hartford, Connecticut and worked in the “Magic Auto Machine Shop” operating a screw lathe. More than once, I worked the sugar beet harvest in Greeley, Colorado.

I enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps. While with the CCC I was working at Camp F-24, Hill City, South Dakota, Zone of Interior (my CCC serial no. was CC7-417209, designating Seventh Corps Area –ed) and although I was officially a cook, I couldn’t cook! So I became part of the Company workers. Our main job consisted in keeping the rocks cleared from the base of Mt. Rushmore while they were chipping out the faces of the Presidents. I was in the three Cs fr om 7 November 1941 until 3 January 1942. As my 18th birthday approached (9 February 1924), I decided to return to Arkansas to register for the Draft. After registering and while waiting to be drafted, I still did anything to work including one more trip to Greeley, Colorado for another sugar beet harvest. When I was notified to report to the Induction Station, I had already traveled quite a lot for my age, and I had worked many unskilled labor jobs with only a 9th grade education. I was just 18 years old.

On 21 January 1943, I passed my induction physical and was assigned US Army Service Number 38508482. I was told to report into active service in the Army of the United States on 4 June 1943, at Camp Joseph T. Robinson, Little Rock, Arkansas (Infantry Replacement Training Center, acreage: 42,124, troop capacity: 2,596 Officers and 44,077 Enlisted Men –ed).

Training:

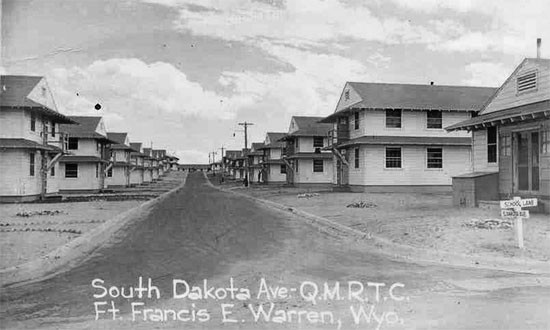

Fort Francis E. Warren, Cheyenne, Wyoming was the “Quartermaster Unit Training Center & Army Service Forces Training Center”. Its total acreage was: 94,874; its troop capacity: 665 Officers and 16,518 Enlisted Men. The day I arrived for Basic Training at Fort Warren, I had two major things happen to me. First, I had no idea about the plan the Army had for me, and second, I met Lewis C. Farrow from Phoenix, Arizona (Private Lewis C. Farrow, QMC, 39416033). The 607th QM GR Co had meanwhile moved by rail to Fort Warren on 17 September 1944, reaching its new station by 19 September.

Basic Training wasn’t easy but I think I had it easier than a lot of the guys. I was 5’10”, weighed 135lbs and all muscle. I was used to work, I was plowing a corn field behind a horse when I was 6, and had spent nearly 3 months in the CCC which was operated a lot like the military. I guess the biggest problem I had in Basic Training was the Lieutenant always yelling at me:“Little, WIPE THAT DAMN SMILE OFF YOUR FACE”! I believe the Lieutenant thought I was doing it on purpose just to spite him, but I really didn’t know I was smiling until it was too late! My Basic Training lasted 3 months, after which I became a Quartermaster Corps Private, MOS # 521.

After Basic Training, Lew Farrow and I along with a few others were surprised to be told we would be transferring on Post to do our advanced training as Light Truck Drivers (Military Occupational Specialty # 345, applied to servicemen driving an automobile or a truck up to 2 1/2-ton capacity carrying personnel or equipment; the man could be a chauffeur, ambulance driver, automotive equipment operator, dispatcher, or a truckmaster –ed). We both fully expected to be sent to the Infantry, but not wanting to argue with the wisdom of the US Army, we did what we were told.

Truck Driver training was also not that difficult for me. Being raised on a farm during the Depression years and working across the West, I was used to doing my own mechanic work on equipment and driving the bigger trucks was a breeze. Also, being from Madison County in the Ozark Mountains gave me the advantage while the Army taught us to drive in adverse conditions. Madison County didn’t have any paved roads or bridges then! The only new thing to me was the transfer case with upper/lower gear ranges and 2/4 wheel drive. I had never seen a 4-wheel drive vehicle before.

Partial view of barracks at Fort Francis E. Warren, Cheyenne, Wyoming, (Army Service Forces Training Center), where the 607th QM GR Co would remain from September 19 until December 31, 1943.

I guess the hardest thing about Truck Driver training came at the end of our traineeship, when they broke us up into 6-man teams to disassemble the engine and transfer case on a truck. Then we had to put them back together all without any supervision. They said all 6 of us would fail if it didn’t run and drive after we put it back together. Ours ran alright and I don’t remember anyone’s failing to run.

At morning formation the day after we graduated Truck Driver Training and were issued our official Driver Permit, names were being called out assigning us to different Commands all over the U.S. To my surprise, Lew Farrows’ name and mine were called together and we were told to report across the street to the 607th Graves Registration Company for Specialized Training. Farrow and I grabbed our duffle bags and walked across the street, both of us smiling ear to ear thinking how lucky we were not to be assigned to one of those “commands that everyone dreaded being assigned to”. Farrow and I were still walking the same trail together and that trail was taking us to the 607th. For the first time since I was drafted, I found that I was walking into something that I had no idea what was going on?

The 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company was constituted and activated at Vancouver Barracks (Staging area for the Seattle Port of Embarkation – ed), Washington, 15 July 1943, and was transferred to Fort Warren, Cheyenne, Wyoming (nicknamed Splinter City) for further training where it would remain from 19 September 1943 until 11 March, 1944 when its Specialized Training would be completed. Just before Christmas 1943 the “official” classroom and mock combat company training ended. But after the New Year began in 1944, the Company continued its training of what had already been learned. This continued training continued over and over… It is my belief that most likely the CO knew our future or at least suspected it and did what any good Commander would do and that was to continue to hone his Company’s skills thru training, training, and more training.

We soon learned what was going on. It was no longer about us training as individuals. We were now part of a Company that we were going to remain part of no matter what the Army had planned for the 607th. At the 607th QM GR Co there was already a command structure in place but the buildings were empty compared to all of the previous training units we had been stuffed into, now that was about to change. Within a day or so, other soldiers started reporting almost constantly and within what I remember being about a week, Farrow and I were once again in a Company that seemed stuffed. The difference is they weren’t all Privates, they had arrived in small groups of 1 or 2 or sometimes up to 5 or 6, from different Posts, Stations, or Training Centers in the Zone of Interior. There were Privates like us alright, but there were also Technical Sergeants, Staff Sergeants, Technicians 3d Grade, and Buck Sergeants, all joining the 607th for Specialized or Technical Training as it was called.

As the fillers arrived we were assigned to Platoons, Headquarters Platoon, First, Second, Third and Fourth Platoon. I ended up in the Second while Lewis Farrow went to Fourth Platoon. HQ Platoon consisted of the Commanding Officer, the Executive Officer, the First Sergeant, Office Personnel, Cooks, Supply and a number of other Enlisted Men who would run the Company and take care of the men. First thru Fourth Platoons were mirror images of each other and they included a couple of Truck Drivers like Farrow and me, but they also included Morticians, Topographic Draftsmen, Medical Aidmen, Surveyors and others. It seemed strange to me that I was no longer in a unit of truck drivers.

1 November, 1943 our Company began 6 weeks of intensive Specialized Training. I thought I would somehow be getting more Truck Driver Training but boy was I wrong. Although we all had received different Individual Training or Special Skills, all of us would get the same Graves Registration Training.

During those special weeks of training we were informed about the functions of Graves Registration Service personnel and were instructed in the proper procedures to respect with regard to the dead and the establishment of Military Cemeteries. In the field, our main job was to retrieve the dead on the battlefield. We would however, when no other personnel was available, select the site and do the plotting (including sketches, maps, and coordinates) of the cemetery ourselves, including the marking and official recording of the graves until permanent burial was accomplished (or the remains were returned to the next-of-kin). Collecting, grouping, and burying the dead was in accordance with regulations, in order to reduce the number of isolated or single graves to a minimum. The process furthermore included receipt, collection, and disposition of all personal effects found on the dead and return them to the United States.

I remember that as far as burial in a cemetery was concerned, we had the following basic instructions to follow:

- Graves to be a minimum of 5 feet deep

- All interments to be made with heads in the same direction

- Marker to be placed at the head of the grave

- All graves to be numbered consecutively, starting with No. 1 at left

- All graves should be in line with one another, both laterally and longitudinally

- The North should be shown on all plans and sketches

In active combat areas, urgency prevailed. Indeed, it was imperative for sanitary reasons and for preserving morale among friendly forces, where conditions were practically stationary. This implied that operations always remained hazardous. There was almost no time to search the body, to remove personal effects, to verify and dispose of dog tags, and no time for records. An ordinary stick, a large rock, an abandoned vehicle, a particular landmark, or a rifle with bayonet stuck in the ground and a superimposed helmet on top would generally be used to indicate the location of a soldier’s body. It was then up to us, to move in, as soon as hostile activities were diminishing and forward movements continued, to start looking for the dead, and after due processing, bury them in the nearest established cemetery!

Identification and interment were very important functions of Graves Registration personnel. Processing usually started with collecting any identifying items, and if such action was impossible, fingerprints of all 10 fingers and complete dental charts would be taken. Careful search would once more take place before burial, and after the bodies had been fully identified and were ready for interment, they were to be wrapped in white mattress covers for burial. Paperwork and preparing the necessary Reports of Interments was the next phase.

One bone chilling November morning, we were shaken out of our warm bunks to go get some “Specialized Conditioning Training”. After a hurried breakfast we loaded into weapons carriers and jeeps. I drove a ¾-ton WC as the guys pulled up their collars, wrapped themselves in their overcoats and tightly jammed their hands into their coat pockets and tried to sleep. The convoy hastened from the Post, speeding thru the empty streets of Cheyenne. I didn’t know where we were going or why, I just followed the truck in front of me. Before long we had convoyed 100 miles and had arrived at the Denver City Hospital, this was mid-November of 1943.

We all detrucked and were herded thru a corridor to a room that I can only describe as a sort of Football Stadium with the playing field being an Autopsy Table with a covered body on it. Shortly, the Coroner and his assistant walked into the room and without hesitation started his examination. The patient was an unidentified young man who had collapsed and died on the streets of Denver. The Coroner explained his job was to determine the cause of death. He was very thorough and completely dissected the body using his knives, scalpels, saws, hammer and chisels. The only undissected portions of the body were the lower legs and arms. At different steps throughout the autopsy, some of the boys left the room. It was like the next step of the autopsy seemed worse than the previous and right up till the end, one or two men would turn and leave, their faces white. I noticed neither rank nor age was relevant.

It didn’t seem to bother me because I had been involved in processing farm animals and wild game for food all my life. As the oldest boy in the family, separating the internal organs from the rest of the intestines of an animal was my job. The heart, liver, kidneys, brains and testicles were all meat for the family, and not to be wasted! As far as it being a human body, I had learned as a young child that the body of the deceased was just a shell. Where we lived in the Ozark Mountains it was 25 miles, almost a full day’s trip to an undertaker, who charged for their embalming services.

In our community when a person passed away from old age or from an accident, the body would be cleaned up and displayed in the person’s home. Most all of the neighbors would come to pay their respects to the deceased and the family. The next day the person would be buried in the local cemetery with the whole community attending the funeral. School would even be let out to go to the open casket funeral and pay their respects. At the funeral or a day or two later, Dr. Dickson would come by and fill out a death certificate and file it the next time he was at the Madison County Courthouse.

When the Coroner finished with his autopsy, he asked if there were any questions? No one said anything. Then he said: “OK, I’ve done my job, now you do your job, someone put this body back together”! I hadn’t really realized it but during the autopsy, I had been shuffled from about half way back in the pack forward, and I was standing almost next to the table. I took a step forward, pushed up my sleeves and put the parts back.

After, the Coroner announced his autopsy was complete, someone bellowed for us to take a break outside. The fresh cold air smelled good, but after what seemed like a very short time, someone ordered us to go back in. When we entered, there was another covered body on the table. This “Special Conditioning Training” lasted all day long only broken by lunch. While convoying back to Fort Warren that evening everyone seemed distant and there wasn’t much of the usual joking. As I was driving back, I remember thinking “Graves Registration’s not that bad”.

Once I realized handling the deceased and processing them properly was just a system of steps to be repeated, it almost seemed easy for me. Farrow didn’t have as much of the same experiences I had had while growing up, but he was raised on a farm and he was doing just fine. As training continued, Farrow and I would laugh sometimes at the comments made by the higher rank guys who had had specific training like Surveyor or Draftsman. These guys were already certified in civilian life at their skills, but they would have to attend “Army Training” courses that were tailored for their specialty. At the end of the day it was funny to hear them talk about “Learning it the Army way”!

The day came when the 607th was to prove all of its training was complete and we were “COMBAT READY”!

Yet, more field training was to follow. One of the organization’s next destinations was Camp Guernsey, built on the remains of a former CCC camp, which was a training site at least a hundred miles north or Fort Francis E. Warren (Guernsey Maneuver Area, Guernsey, Wyoming, Bivouac Maneuver Area specifically used by Fort Francis E. Warren, Wyoming, total acreage: 4,500 –ed). We moved by motor convoy up there and I don’t remember what other units were in the area but it seemed like hundreds and hundreds of troops at this very large training site. I guess we remained for about 2 weeks and conducted full combat gear field training with us part of the time representing the defenders and part of the time the attackers. We had blank ammo, blank artillery shells, blank smoke, and we would be gassed with CS gas at any time. We would do full night moves from one site to another driving under complete blackout conditions through the hills. During the nights without exercises, we slept in pyramidal tents. Along with the combat training, we were tasked to go out as small teams and locate casualties (straw stuffed gunny sacks) and transport them to predetermined collection points to be partially processed or just turned over to the CP personnel for them to evacuate the casualties to an established cemetery that others had set up. Map making and surveying activities were not forgotten. It was quite a lot of field problems that we tackled, but we took the exercises very seriously because we all knew it could very possibly become a reality.

During our stay at Camp Guernsey, I rarely saw Lew Farrow because our Platoons began to operate independent of each other. I had no idea why, they kept separating us. I was of the impression that we could do more together than separate but once again the Army had plans for us way above my pay grade. Anyway, I was satisfied when I heard the 607th as a whole would be moving. Platoon Sergeant (Staff Sergeant) Norman L. Beadles, QMC, 37611346, said: “Pack up, we’re joining the Company”.

It was the middle of the afternoon, it was cold with snow only broken up by mud in parts of the road. I don’t have any idea how many miles we had marched. As a Company, the 607th was led by the Captain in his jeep, with the Platoons following in order with each Platoon Leader, leading his outfit in his ¼-ton truck, followed by the men trudging along in full combat gear (60lbs).

Photograph illustrating Staff Sergeants Eugene Gimbel and Albert Pauly at Fort Francis E. Warren, Cheyenne, Wyoming. Photo taken prior to the unit’s oversea movement, end 1943, early 1944.

I don’t remember exactly why, but I believe the CO’s jeep simply slipped off the road into the ditch. Anyway, we halted and I was on the right side next to where the vehicle had slid into the ditch. I can’t remember who was driving but he revved and slung mud and snow and revved and got deeper and deeper and finally stopped. That’s where I met First Lieutenant Ernest J. Terry, Second Platoon Leader, QMC, O-1581416. I knew who he was, but as a Private I had never had any contact with him. Lieutenant E. J. Terry said; “Six of you guys come over here and lift this jeep out of the ditch”. As we were dropping our packs and rifles, I was dreading stepping into that ditch and getting my feet wetter and muddier than they already were. I said: “Hey Lieutenant”, I can get that jeep out of there”. He said: “How are you going to do that”? I replied: “Drive it Sir”. He said: “Well then – Do it”! So I went over and got into the jeep, noticed it wasn’t even in 4-wheel drive; jammed the transfer case in 4-wheel drive, moved the other lever into low transfer, started it up, put it in second gear, revved the engine and popped the clutch and that damn truck jumped about 6 feet right out into the middle of the road. After the cheering stopped, the Lieutenant told the other Private to remove his rifle and pack from the jeep and ordered me to get my stuff and put it in the truck, and that’s when I became First Lieutenant Terry’s driver.

I thought the 607th performed admirably during our Field Training Exercise at Camp Guernsey and following more convoy practice and motor marches Christmas was soon upon us. Our unit returned to Fort Warren 16 December 1943. We heard there was going to be a Christmas furlough, and I had already made arrangements to head out on the bus as soon as we were released. The Captain held Company formation and said he was giving the 607th QM GR Co a 5-day Christmas furlough! He then said: “I only have one requirement, Men. If you’re leaving Fort Warren to go home, you’d better be back in 5 days or you’ll be reported as AWOL!” He repeated himself again and said; “If you can’t make it back on time DON’T GO”!

In the winter of 1943, I left Fort Francis E. Warren, Wyoming, for Kingston, Arkansas, on a bus to marry my sweetheart, Lois Louise White. There were three reasons I wanted to marry Lois, I loved her, I wasn’t related to her (small town Ozark Mountains joke) and we had known each other since we were babies. In fact our parents always joked about Lois and I sleeping together when we were 6 months old. It seems that when we were babies our parents attended a music party at the same house and they put Lois and I to sleep on the same bed. So, we were married, 27 December 1943. The very next morning, I boarded the bus in Arkansas heading back to Fort Warren. The bus was originally scheduled to arrive on the night of the 5th day or furlough, but right away we ran head on into a snow storm and by the time we got to Kansas City, the bus driver was already talking about running behind schedule. To make a long story short, it never quit snowing and I wasn’t back with the Company until a full day late!

Although I sent a telegram letting the Captain know that due to the snow storm, I was coming in late. Captain Whitman Pearson had no sympathy. He was very mad and kept telling me that I had been warned. Then when the Captain found that I had gotten married (something I didn’t know I had to have permission to do) the Officer was furious and stayed good on his promise. I received a Company Grade Article 15 for being AWOL. Remember when I said I thought the 607th had done real good at the Camp Guernsey maneuvers? Well, apparently the Company hadn’t done as well as “I thought” and starting in January of 1944, the 607th trained over and over and over on everything. Of course in addition to all the repetitive training, I was pulling extra duty for being AWOL every time there was the slightest break in the training. Lew Farrow who was already married, thought it was funny and kept asking me if it was worth it? It was!

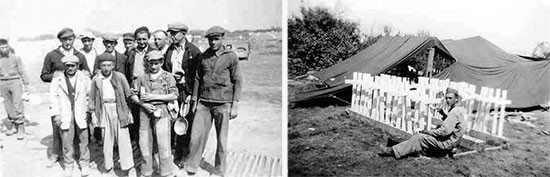

Photo illustrating members of Second Platoon, 607th QM GR Co, during their stay at Denver City Hospital for some aspects of training. This photo was taken in November 1943.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

As First Lieutenant Ernest J. Terry’s driver, I had heard the scuttlebutt, and then just days before 11 March 1944, the 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company was alerted to “Prepare for Departure”. But was this just another training test?

So, on this cold gray morning of March 1944, we started boarding the long train of troop cars. We had everything we owned with us for combat including our cal. 30 M1 carbines. If this was another phase of our training then it was very realistic because we had left nothing, NOTHING behind! Ok, we’re leaving for good! No one seemed to know our destination, and it was even rumored that the Officers didn’t know and wouldn’t find out until they opened their orders after we were underway.

The train was a rest for me, I took every chance to slumber half asleep in my seat after what had seemed like an endless period of time that I was on extra duty, but that was over now. Others stood in the windows, seeming hypnotized by the passing scenery. Farrow, with a smile on his face still took every chance to ask me if I was resting ok. Other than the rotating KP duty, our job was to ride the train, and ride the train we did! For 4 consecutive days we headed east until we finally stopped in Massachusetts where we would spend a week at Camp Myles Standish (Staging Area for Boston Port of Embarkation –ed). After equipment was cleaned and barracks bags were repacked there was nothing to do so the Officers, Platoon Sergeants and Section Leaders would come around and inspect our equipment and hold periodic briefings just to break up boredom. Many of the men played cards, read books, wrote letters, or slept.

Photograph illustrating USAT “Edmund B. Alexander”, which carried the 607th QM GR Co across the Atlantic. She left Boston, Massachusetts March 23, 1944, part of a large convoy, reaching the United Kingdom after an uneventful journey on April 3, 1944.

All of a sudden we were once more on the go, we were loaded on another train and a short time later, we reached Boston Harbor. This was completely different than where we had just left. The harbor was busy, full of troops already packed and going up the gangplank. Soon Captain W. Pearson (CO, 607th QM GR Co) appeared, gathered all the Platoon Leaders and Platoon Sergeants around him and a short time later the CO and the other Officers boarded the ship and we didn’t see them until after we were underway. The NCOs directed us aboard and down and down and down almost to the very bottom of the ship to our assigned area. We stayed there, and on the early morning of 23 March 1944, the USAT “Edmund B. Alexander” was underway. We had assigned bunk cards which also functioned as meal tickets. After we were underway, movement restrictions were lifted and we were allowed to go topside. Smoking was however not allowed below deck so there was a lot of guys on deck by the time I got all the way topside. Farrow and I were assigned bunks in our separate Platoon areas so we barely saw each other except in passing or on deck.

I never counted 27, but it was said by many that they had counted 27 ships in our convoy, and it certainly was an awesome sight. Ship life was cramped, no privacy, most everyone was sick, water was limited, life jackets were to be worn, abandon ship drills were conducted, on deck calisthenics were organized, the chow line was an hour long and we had to eat standing at narrow tables with edges to prevent your plate from sliding off. We encountered a storm on the last days of our journey that felt like it almost stopped the ship. The wind was very hard, creating huge waves that caused the ship to violently rock from side to side. At times water was breaking over the bow enough that the order confining us to quarters was given. Eventually the seas calmed and I knew for certain I never wanted to serve in the Navy!

On 3 April 1944 land was spotted on the horizon. Everyone was ready to leave ship but it wasn’t time yet. After spotting land I don’t know how long it was before we unloaded but we passed along the coasts of Northern Ireland and Scotland and into the calm waters of the Irish Sea. As the convoy split up we were positioned outside Liverpool Harbor when a heavy wet fog dropped like a curtain over us. Visibility became zero and we weren’t able to unload until the fog lifted. I believe we sat there for a couple of days, bored and cramped together, then all of a sudden the Captain appeared on the staircase and after getting everyone’s attention, announced that we were going ashore at Liverpool, England. The fog had lifted! It was 5 April 1944.

United Kingdom:

As we arrived in the United Kingdom, I heard some of the guys talking about all the antiaircraft balloons tethered over the island. They said it looked like the whole country was about to sink because of all the military equipment, and the only thing holding it up was the balloons. I stopped for a moment and stared at the sight. I thought to myself, it actually did look like the island could sink if the balloons weren’t holding it up.

The next 2 months in England and Wales everything became a blur. We moved by day, we moved by night. We moved by train, we moved by bus. We stayed in a makeshift tented camp, near a tiny village (near Oxford, designated Camp Besselsleigh, –ed) that had obviously just been deserted by other troops, soldiers on the same path that we were on and at one point we were actually billeted in civilian homes. Sometimes it seemed that the Company couldn’t keep up with the pace needed while moving and other times it seemed that we had moved too fast and would have to stop and wait as a penalty.

hotographs illustrating some aspects of the training during “Exercise Tiger”, and the damages caused by the German naval surprise attack to some of the ships (LST 289) participating in the exercise. Period April 22-30 April 1944. First Platoon took some heavy losses during the attack.

There was military equipment stocked and piled along roads, in fields, just everywhere mile after mile. Looking back on it, it was truly unbelievable. I had no idea at that time, but there were over 2 million American, Canadian, British and Allied fighting men along with millions and millions of tons of invasion supplies that had poured thru English ports in preparation for “Operation Overlord”.

At one point the 607th QM GR Co was issued its organic vehicles, and shortly after that we were off, and this time we were heading for our final destination.

On 15 April 1944, in compliance with First United States Army orders, the 607th was split up. Company Headquarters and Fourth Platoon were to move to Knowle Camp, Bristol, England; Second Platoon would travel to Swansea, Wales; First Platoon was to move to Truro, England; and Third Platoon would leave for Paignton, England.

Following further training and maneuvers at Swansea, Wales, we began serious preparations for crossing the Channel and moving to the Continent. Our Company, attached to the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, was intended to participate in the D-Day landings (6 June 1944), but due to rough weather and problems on the beachhead, debarkation was postponed to D+2.

Then the shocking news came in. Almost the whole First Platoon of the 607th had been lost at sea (16 men killed, and 1 wounded –ed) during a Naval Training Operation in April (Exercise “Tiger” –ed). Immediately I wondered: “How could this happen”? It didn’t make sense to me! I didn’t even know they got on a ship. I didn’t even know they weren’t with us. During one of the briefings around end April,; we weren’t in a traditional formation but gathered in a semi-circle type of group actually sitting on the ground. I looked around and realized there were faces missing. First Platoon was 25% of us, we had all been training together all the way back to those first days we joined as strangers. Lew Farrow and I just looked at each other.

The Captain told us all he could which wasn’t much, but he did say he would tell us the names of the deceased when he was informed. Although we did find out the names of the lost, it was not until long after the Invasion that we would find out that First Platoon was part of a secret Pre-Invasion Naval Operation called Exercise “Tiger” (held from 22 to 30 April 1944 –ed). They were aboard an LST (LST # 531 –ed) with the 1st Engineer Special Brigade practicing landing and assault in a place called Slapton Sands, when the convoy was attacked by German E-boats! A total of 749 troops were killed.

Movements United Kingdom – Second Platoon, 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

15 April 1944 > Swansea, United Kingdom

10 May 1944 > St. Austell, United Kingdom

I thought we were still somewhere in Swansea, Wales until First Lieutenant E. J. Terry said St. Austell, Cornwall, would be our last stop (which involved traveling southward another 95 miles –ed). With the exception of all the military equipment jamming every square inch of space on land, it was actually a beautiful place. I had never seen such a setting, having lived most of my life in the Central and Mid-Western United States. Even as a young man, I remember thinking, this was once a peaceful quiet town filled with free happy people. Now they flew tethered balloons overhead by day and huddled in their houses with blackout curtains on their windows by night. For a moment I thought about my wife and the people back in Kingston.

Portrait of Captain Ernest J. Terry, QMC, O-1581416, Second Platoon Leader, 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company. Photo taken after November 1944, following his promotion from First Lieutenant to Captain. The Officer was eventually transferred to the 3059th QM GR Co.

We had to go on, but our stay in St. Austell now seemed an eternity. After we marked our vehicles and personal equipment with ordered military markings, we were basically bored, waiting to go. “What’s the problem, let’s go”! We had followed every order, accomplished every training task expected of us, had lost 25% of our Company, so: “Let’s Go”!

Finally, the order was given. Second, Third and Fourth Platoons (Fourth Platoon actually fulfilled the role of First Platoon, which it replaced, while the latter was sent away to Bristol for replacements and training) all went in separate directions. Farrow and I nodded at each other and went our own way (Private L. C. Farrow was to join Fourth Platoon, heading for Utah Beach –ed). As the Second Platoon jeep driver, I was relieved to be directed to board the LST first, I thought: “Great! – I’ll be the last off”. We tied down our vehicles, took our places and once again waited. Then all of a sudden the Navy boys started scurrying around the LST and before we knew it we were moving along, part of a huge convoy of all types of ships, on its way across the English Channel.

I didn’t realize it then, but the 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company was assigned to the First United States Army, commanded by General Omar N. Bradley. We were to go ashore on D-Day + 1. Fourth Platoon (CO, First Lieutenant William O. Davis –ed) was replacing First Platoon and had boarded an LST together with troops of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade which headed for Utah Beach. Second Platoon (CO, First Lieutenant Ernest J. Terry –ed) was aboard an LST with the 5th Engineer Special Brigade headed for the Eastern half of Omaha Beach, codenamed “Easy Red” and Third Platoon (CO, First Lieutenant Robert E. Berry –ed) was aboard another LST together with elements of the 6th Engineer Special Brigade headed for the Western half of Omaha Beach , codenamed “Dog Green”.

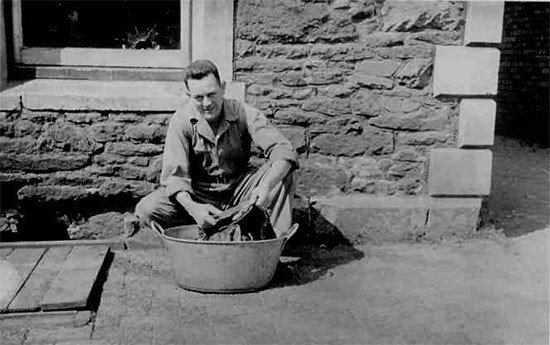

Photo illustrating Technician 5th Grade Stephen M. Benton, Fourth Platoon, 607th QM GR Co, washing some clothes, while being stationed at Camp Knowle, Bristol, England

France:

On the morning of D-Day we were about 10 miles off shore and the only way I can describe the snapshot that appears in my mind when asked, is that it was like looking at a chalkboard I’ve seen on TV with Basketball or Football Coaches drawing out plans where the players identified as Xs and Os move this way and that way and circling around. The only difference being that these were boats filled with men moving with the white churning trail of water behind them instead of a chalk line on a blackboard. The LSTs and other big ships were Xs and the smaller landing crafts were Os or little dots. Once the invasion started, most of the time we couldn’t actually see the shore for all the smoke and dust, but the constant circling and lines of ships and boats going in continued all day.

Overnight it was completely dark and as dawn began, we saw that we had been slowly shifting closer to the shore and were now close enough to see the beach where we were to land fairly well, I would say 3 to 5 miles offshore. We didn’t know it, but just about in the afternoon of D-Day, Third Platoon, 607th QM GR Co had been put ashore early with the 6th Special Engineer Brigade. Apparently, a bulldozer was needed to help clear the clogged beach of the carnage of the day’s fighting and the 6th ESB with the Company’s Third Platoon was ordered ashore. Ironically, Third Platoon landed on “Easy Red” (our landing site) and after spending the night in place, it traversed Omaha Beach almost a mile the early morning of D+1 to reach the “Dog Green” landing area on the Western end of Omaha Beach to begin their job.

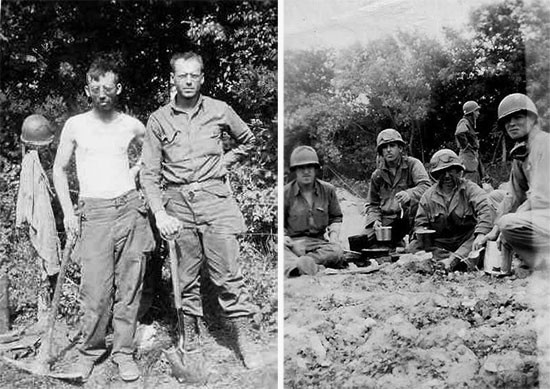

Omaha Beach operations. From L to R: Sergeants Carroll K. Moore and Luvern C. Whitson take a short rest. Second Platoon personnel having chow while serving on Easy Red Beach June 8, 1944. From L to R: Private First Class Nick H. Cobble, Technician 5th Grade Herculano E. Esquibel, Technical Sergeant Norman L. Beadles (rear), Private Eugene R. Worley, and Private First Class John D. Little (far right).

Our Platoon (Second Platoon, 607th QM GR Co) was supposed to go ashore on “Easy Red” on D+1 but couldn’t land until D+2 because the landing beach sector was clogged from the intense fighting that had taken place on 6 June 1944. There was so much wreckage and debris in the water and in the landing area and moreover, severe fighting was still taking place on the bluffs overlooking “Easy Red Beach”.

Our CO, First Lieutenant Ernest J. Terry and Platoon Sergeant Norman L. Beadles informed us that due to the congestion on the beach and continued fighting on the bluffs over the beach we might have to sit tight aboard ship overnight before going ashore. Now I thought we were in too close to spend the day because the water randomly exploded as enemy artillery shells hit out where we were. A couple of times very close! It was during the evening of D+1 that I saw my first American casualty. A sailor slowly floated past our LST. Someone said he was most likely a Higgins coxswain drifting out with the tide.

At 1145 hours, on the morning of D+2, i.e. 8 June 1944, our Platoon landed on “Easy Red”, Omaha Beach, together with elements pertaining to the 5th Engineer Special Brigade. Much of the water was the color of blood.

We immediately moved to within about a half mile off-shore. The front doors of the LST opened, the ramp dropped and, all of a sudden “Dukws” started bobbing away towards the beach. As I was unshackling my jeep from the deck, I would glimpse towards the amphibian trucks heading ashore and they looked like they were filled with supplies and some soldiers. Hell, I didn’t even know they were below! I had seen a few soldiers come and go from below deck, but I didn’t know there were that many trucks down there!

A deck hand motioned for me to get moving so Lieutenant Terry and I drove to the elevator that we came up on. Another man threw a handle and we started back down to the bowels of the ship. It was empty just like it was when we loaded. A sailor pointed and yelled: “Move It”! All of a sudden I came to a wall where another sailor was standing and he said: “Now when those doors open, and that ramp drops, you hit it, and don’t stop”! What? I thought; “First On, Last Off”, not “First on, First Off”? Maybe being in the Navy wouldn’t be so bad. It was close to midday.

Utah Beach operations. From L ro R: 1st Engineer Special Brigade Officers confer with 1st Lieutenant Neal F. Raker, Fourth Platoon Leader, 607th QM GR Co, June 7-8, 1944. Sainte-Mère-Eglise Cemetery; Plot B reserved for 4th Infantry Division dead.

Vehicles filled in behind us, I felt the front of the ship slowly touch the beach under us, heart pounding, the doors opened, the ramp dropped and I “Hit it”! The jeep entered the red (bloody) waters and leveled off at about 2 feet deep. All of a sudden I wasn’t worried about drowning anymore, (I had sealed the engine’s distributor and spark plugs with cosmoline, and the jeep had a deep water carburetor breathing system so it would presumably run underwater even if I left the truck or drowned) but now I had to maneuver the beach. Maneuvering the beach wasn’t easy because despite all the travels and experiences in my young life, no experience or no amount of training could prepare me for the immediate destruction I saw when the doors of the LST opened.

I was driving, but for a moment it was like I was setting in a seat at a movie theater with red carpet and the curtains had opened to a movie already in progress. After that brief moment, I could smell the aftermath of the invasion, it was smoke, rubber, gunpowder, fuel and already the stench of decomposing bodies filling my nose. There was twisted burnt metal and bodies, pieces of vehicles, parts of soldiers. Some vehicles were sitting like nothing was wrong with them and I wondered if the driver had drowned and the vehicle idled ashore by itself, some soldiers were lying with no apparent wounds like they were just asleep. First Lieutenant Terry knew where we were going and kept directing me in and around stuff until we picked up a beach trail, then he said take left and that took us up to the top of the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. When we arrived at the top, he ordered another left and then to stop. This would become the location of the Temporary St. Laurent-sur-Mer # 1 Cemetery.

Moments later, Staff Sergeant Norman L. Beadles and the remainder of Second Platoon arrived at our location. With the constant noise of the ongoing battle just out of sight, First Lieutenant Ernest J. Terry, and a couple of the Section NCOs checked the map coordinates to verify our predetermined location on top of the bluff and then the order was given to establish the Platoon CP. Everyone immediately knew what to do thanks to the constant and efficient training we had received back at Fort Warren! After we set up the Platoon CP with our pup tents individually pitched amongst the cover of the tree line, instructions were given to return to the beach.

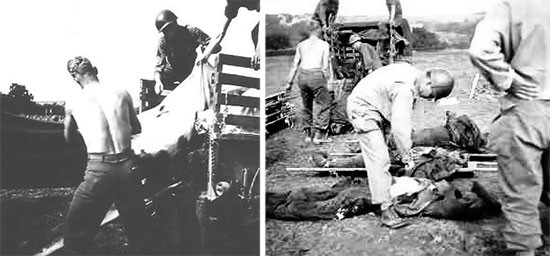

D-Day dead recently disinterred from Omaha Beach are being assembled for reburial at the permanent Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer Cemetery # 1.

Everyone’s faces were now emotionless. No jokes or smiles, no anger or sadness, just taught faces. After joining a unit that I was not familiar with at all, it now became clear to me. We had come together at the 607th with a lot of different skills in our backgrounds, but added to those skills was the “specialized” training the 607th had given us, and now being very highly trained, we were the soldiers that would be responsible for the task that would fill the Cemeteries of World War Two! Now I knew what it meant to be a member of the 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company! Now I would know what it meant to process the dead before they filled those graves!

For Omaha Beach the initial plan for burial operations within the Beach Maintenance Area envisaged the opening of 2 cemeteries in coordination with V US Corps. One, in the 5th ESB area (southeast of Ste. Honorine-des-Pertes) and another in the 6th ESB area (near Cricqueville-en-Bessin). They were to be opened as soon as the situation permitted.

Responsibility for the collection of the dead and their transportation was laid upon the CO of the Battalion Beach groups, each of whom was to designate an Officer as Graves Registration Officer to supervise this activity. One Platoon of the 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company was to be attached to each of the Engineer Special Brigades to take charge of the layout of the cemeteries, the identification and burial of the dead, the registration of the graves, and the collection and disposition of all personal effects (ref. Circular No. 55, First United States Army, dated 28 April 1944: Operation Plan “Neptune”, First US Army, Annex No. 7e, dated 7 February 1944).

On the landing beach the Platoon came together. It would take a while for the Temporay Cemetery overlooking “Easy Red”, Omaha Beach, to be ready for interment, so the orders were given:

- Take care of those boys!

- Do it before the replacements start coming ashore!

Collecting and burial operations at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer Cemetery # 1, established by Second Platoon, 607th QM GR Co. Left photo; from L to R: Private First Class Chester F. Stein and Sergeant Roy Steinhauser. Right photo; from L to R: Staff Sergeant Adolph H. Herberts, Staff Sergeant Vito Mastrangelo, and Private First Class Irwin W. Kestner gently lower a body into its last resting place (further right a Chaplain says prayers).

So, on the afternoon of 8 June, I drove Second Platoon Leader, First Lieutenant Ernest J. Terry, O-1581418, Second Platoon Sergeant, Staff Sergeant Norman L. Beadles, 37611346, and Second Platoon Surveyor, Staff Sergeant Adolph H. Herberts, 36475775, back to our CP above the beach where they began to lay out the temporary cemetery (nicknamed the “Bluff Cemetery”), later to become designated St. Laurent-sur-Mer # 1. As the Platoon driver, I was often around our Platoon Leader and our Sergeant driving them around, while conducting operations on Omaha Beach and beyond the beachhead. Thus I had a somewhat larger view of the overall operation than if I hadn’t been appointed the Lieutenant’s driver.

(it was clear that prescribed procedures could not be carried out due to the number of dead on and behind the beach being much higher than anticipated. The Bluff Cemetery would not be ready and combat troops had not been able to move ahead as originally planned. The Battalion Beach groups were still struggling to open beach exits and move equipment and supplies off the beach and there was not enough adequate labor to collect and bury the dead. Finally, the enemy still occupied sites merely 200 yards from the planned cemetery location –ed).

I remember a small anecdote when operating on Omaha Beach. We were on the beach next to the bluff during late afternoon of D+2. Lieutenant Terry wanted us to have something warm to eat before dark (as we had been eating cold rations since D-Day), so he asked me to cook a warm meal for some of our guys … I told the Platoon Leader; “Hell Sir, I can’t cook”! Terry told me: “You don’t have to cook, just get the men’s rations and warm them up for them…”. So, I looked around and found something that looked like a casserole that could be used for cooking. I cleaned it as best as I could using dirt and sand and rinsing it with water from my canteen. After collecting several C-cans I put them all together in my cooking pot and built a little fire. When it was ready, I called the men and they took turns eating. Some hours later the whole Platoon got sick and suffered stomach issues for a day or two. Well, Lieutenant Terry never asked me to cook again! “I did my best”, I told him I couldn’t cook! Hell, I was sick too!

Burial operations. Left photo: group of French civilians, part of a burying detail, used to supplement American personnel (they would eventually be reinforced by German PWs). Right photo: unknown Private painting wooden crosses for the cemetery.

Since there was no official burial site, the men had no choice but to bury the dead on a selected plot on the upper side of the beach itself since most of the dead had already been there 48 hours. A bulldozer was obtained and trenches were dug 5 feet deep on the beach. In the bottom of the trench, an additional 1 foot was dug about 24 inches wide with about a foot between each grave. That first day, we concentrated on the dead that were closest to us and along the beach road. At times, some of us tried to talk about unrelated things. At times, some of us tried to joke about something. But most of the time, when you looked into someone’s face all you could see was that stare with jaws clenched. The boys were placed into white mattress covers with all their combat gear and temporarily buried on the beach. This continued until well after dark. The number temporarily buried on the beach is not known because history didn’t record this temporary burial by Second Platoon, 607th QM GR Co. But in the first light of D+3, the boys were disinterred, processed and properly buried in the Bluff Cemetery.

In the confusion of those early invasion days on the Normandy beaches, while under enemy artillery and small arms fire, the men of the 607th cleared the beaches of bodies, and searched offshore waters to recover more dead, some of which they had to cut loose from landing craft submerged in the shallow waters. More bodies would wash ashore with the incoming tides, while others were exposed trapped among vessels and barges at low tide.

During the days following the invasion, Second and Third Platoon were able to clear the landing beaches of all the dead (American as well as enemy) and rebury them on the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach, which would eventually become the permanent “Normandy American Cemetery & Memorial”. Eventually two Quartermaster units (colored personnel) were temporarily attached to us, to help with collecting bodies and digging graves. Soon thereafter, German PWs were used to do the digging, guarded by EM of the above Companies. Some of these initially thought they were being forced to dig their own graves, assuming they would shortly be executed, and wept as they worked. Once they saw the graves’ true purpose, they cheered up and became dedicated workers.

On the beaches, we learned the tides and would meet the bodies washing ashore, while at low tide others could be seen, exposed trapped among vessels and barges. A couple of us were good swimmers and were selected to enter the water to retrieve our boys from landing craft submerged in shallow waters. Some were entangled in propellers. My thoughts meandered (while underwater) and I remembered being a very young boy of 5 or 6, lying on a tree limb stretching over the lazy Kings River back home. Then, when I heard dad’s pistol crack, I would jump from the limb into the cool water to feel for the stunned fish before it regained consciousness. If I was successful, that would be our supper. If not, it was a wasted bullet and supper might be light, not to mention dad would be mad at me. We were trained to be respectful to the dead, and we always tried. But no matter how much you try to be respectful, tell me how you can be respectful when you’re underwater holding your breath and cutting someone loose from a propeller that was so entangled and twisted into it that the boat engine was seized? For me, removing them was the worst experience I would ever encounter.

Daily occupations. Left photo: personnel of the 607th QM GR Co having chow at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer Cemetery # 1. Right photo: member of the 607th QM GR Co nailing a Dog Tag onto a wooden cross (preliminary identification of individual grave).

“Easy Red”, huh! There was nothing easy about it! I had seen a lot of dead bodies before I was 19 but they were cleaned and dressed for burial in their Sunday “Go to Meet in Clothes”, unlike those I would eventually recover from the European Battlegrounds before my 21st birthday!

Second Platoon’s location at the Bluff Cemetery would become the temporary Company HQ for the 607th with the Commanding Officer, Headquarters, First, Third, and Fourth Platoons all eventually reunited with our Second Platoon at St. Laurent-sur-Mer #1. I remember seeing Farrow and the other guys and I remember thinking how they had all changed. It didn’t matter that some had seen more and some had seen less, but all had seen and changed forever. I realized that included me. I don’t really remember, but I believe it was about this time that we started getting replacements assigned to the First Platoon, relieving Fourth Platoon from its duty filling in for the lost First Platoon.

(First Platoon finally landed on Omaha Beach 29 June 1944, where it was to join Second and Third Platoon at the new (permanent) St. Laurent-sur-Mer Cemetery # 1. Company Headquarters joined them the following day –ed).

Movements France – Second Platoon, 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

8 June 1944 > Omaha Beach, France

30 June 1944 > Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, France

9 August 1944 > Marigny, France

17 August 1944 > Le Chêne-Guérin, France

22 August 1944 > Gorron, France

29 August 1944 > St. André, France

5 September 1944 > Solers, France

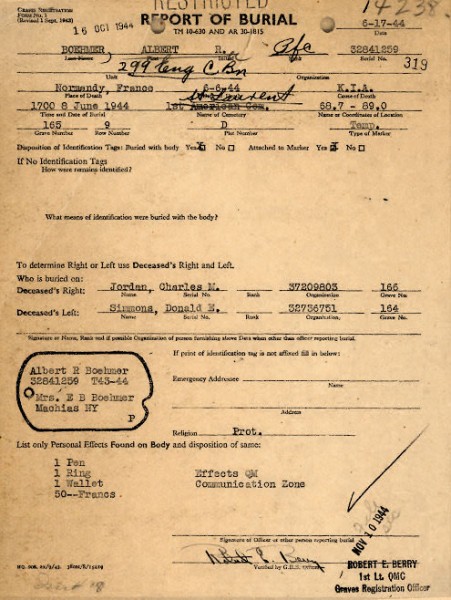

Photograph illustrating Graves Registration Form No. 1, dated June 17, 1944, filled out by First Lieutenant Robert E. Berry, Third Platoon Leader, 607th QM GR Co.

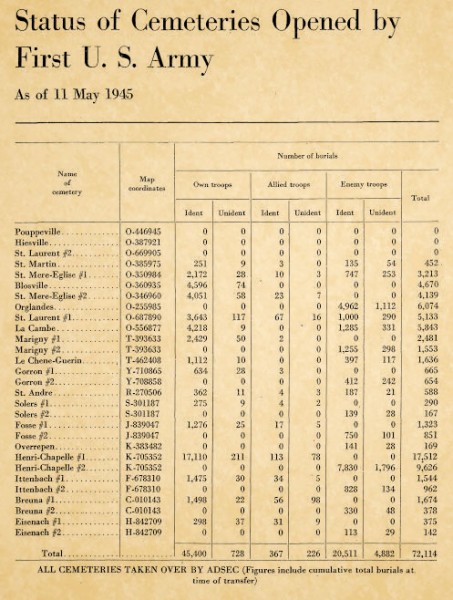

The following numbers of dead had been buried at the American Cemetery St. Laurent-sur-Mer # 1:

| American | Allied | Enemy |

| 3,642 Identified | 67 Identified | 1,000 Identified |

| 118 Unidentified | 16 Unidentified | 290 Unidentified |

While conducting graves registration duties in France, First and Second Platoons were ordered to proceed to Fosses-la-Ville, Belgium. We drove thru Paris on our way, just a couple of weeks or so after it was liberated. The streets were full of people cheering just like you see in the movies. It was now September 1944.

Before leaving France, the 607th established and/or conducted burial operations at the following cemeteries:

| Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer # 1 | La Cambe | Blosville | Orglandes |

| St. Martin-de-Vareville | Sainte-Mère-Eglise | Marigny | Le Chêne-Guérin |

| Gorron | Saint André | Solers |

Belgium:

On 13 September 1944, First and Second Platoons received orders to move from Solers, France to Fosses-la-Ville, Belgium. They were joined by Company Headquarters, Third, and Fourth Platoons as from 17 September.

Once in Belgium, the whole 607th eventually came together at the Henri-Chapelle Cemetery 27 September 1944. Although the cemetery was located only 9 miles west of Aachen, Germany and was still enemy territory, we actually got some down time. During this period, we had no idea that the Henri-Chapelle Cemetery would become the largest American Cemetery of WWII.

I remember the whole operations of the 607th changed after we got to Henri-Chapelle. First Lieutenants Ernest J. Terry and Robert E. Berry got promoted to Captain and in late November, were transferred to take over other Graves Registration Companies. Our Commanding Officer was first sent on DS to the 3059th QM GR Co end November 1944. As he never returned, he was replaced by First Lieutenant John A. Liddie 31 March 1945.

These changes left us without 2 Platoon Leaders for some time and although S/Sgt N. Beadles was still our Platoon Sergeant, I remember Platoons becoming mixed together for missions. I don’t believe it was actually a result of Platoon Leaders being transferred. I believe as missions came up, individuals were picked from the 4 Platoons based on their skills to accomplish missions. Lew Farrow and I were together again and we even bivouacked together for the rest of the war. After First Lieutenant E. Terry left, my platoon driver duties were far and few between. Sometimes S/Sgt Beadles would grab me and a jeep or a weapons carrier for a mission he was on, but basically my platoon driver duties were over.

For me, after we reached Henri-Chapelle, Belgium in September 1944, until I was transferred to Berlin from central Germany in late July or early August of 1945, everything during those 10 months seemed to blur together with the exception of ingrained memories. We worked long days, mostly 6 days a week. At times even 7 days a week. While in Belgium, most of the time our daily job consisted of hundreds of small, medium and large missions. Sometimes we were assigned by one or two Platoons and sometimes we were sent as collecting and burial teams consisting of as few as 2, 3 or 4 or as many as 10 or 15 men made up of mixed Platoon members. We might be sent to a specific area for 2 or 3 days to operate a Collection Point or a Platoon might be attached to an outfit we had to remain with it as it moved along the fight at the front.

The collecting and burial teams of the various Quartermaster Graves Registration Companies had to stick with whatever outfit they were attached to on the front. Our job was to collect the dead and get them out of sight of new troops coming up, which would otherwise be bad for morale. I must say that the stench of decomposing bodies, especially during hot weather, was overpowering and unforgettable! In the period before masks and rubber gloves were distributed and in use, a day’s work would leave each GR soldier covered in blood. Clothes had therefore to be washed in gasoline to remove any possible contamination. Unfortunately, such measures were out of the question as long as the fighting in the area continued.

Collecting and burial operations at Fosses-la-Ville Cemetery. Left photo; 607th QM GR Co personnel processing American dead at Fosses-la-Ville Cemetery # 1. Right photo; personnel identifying and processing German dead at Fosses-la-Ville Cemetery # 2.

Movements Belgium – Second Platoon, 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

13 September 1944 > Fosses-la-Ville, Belgium

27 September 1944 > Henri-Chapelle, Belgium

8 October 1944 > Overeupen, Germany (DS, 1 Off + 20 EM)

My memories of Belgium are mostly that it was a very cold winter! I know we endured the Battle of the Bulge, but the beginning and ending dates meant nothing to me. We were always close to the frontline and were used to conducting daily operations very close to where the fighting took place.

I remember the day a Nazi fighter plane swooped down and strafed the Henri-Chapelle Cemetery and our bivouac area nearby. It was so damn low I could clearly see the pilot’s face.

Buzz bombs were constantly going over us at Henri-Chapelle. I was told we were under the buzz bomb flight path to England. Sometimes the V-1 and/or V-2 would shut off either purposely or prematurely and fall in our area. When they shut off at night, the silence would immediately wake you up. Farrow and I decided there was no reason to run, but many would. One of those flying bombs landed so close it knocked a guy down and out, but he was ok.

On slow days (the 607th QM GR Co was considered to be in a “rest” area, as of 1 October 1944 –ed) two of us would make a daily circle behind the lines to the surrounding Army Field Hospitals to pick up casualties. One time we picked up an Army Nurse Corps Officer or was it a Red Cross girl ? who had been killed. I wasn’t involved with her processing or burial, but I did transport her body to Henri-Chapelle.

I remember processing part of the Malmédy Massacre (at the Baugnez crossroads –ed) victims. The processing took part inside a large tent that had been erected just for these boys. We had to record a more precise cause of death including exact entry and exit wounds if any. We were told it was for possible use in upcoming War Crimes court cases. The bodies froze so fast when they were slaughtered that when the bodies started thawing, they bled like they had just been shot. Water slowly dripped from their eyes and it looked like they were crying. Some of the boys’ muscles would contract or release and they would move their arms or legs, one sat up eyes open (on 24 July 1945, a large wooden cross was erected at Baugnez in memory of the US servicemen, prisoners of war, murdered by the Waffen SS during the German Ardennes Offensive –ed).

Sometimes, during a lull in the fighting, units would bring their fallen comrades to us. I remember Farrow and I going right to the line to pick up casualties. Most of the time the dead would already be laying together at the combat unit CP’s location about 50 yards from the fighting, and if my truck and trailer wasn’t full and the soldiers couldn’t leave the line to evacuate their dead to the CP, we would go right up to the frontlines and retrieve a casualty. During one such occasion, one guy grabbed Farrow’s arm with a wild look and gritting his teeth said: “You take care of him”!

Photographs illustrating 607th QM GR Co personnel at work. Left photo; 607th QM GR Co Collection Point near Fosses-la-Ville Cemetery. From L to R: Private First Class Lewis C. Farrow and in the truck, Sergeant Harold W. Bell. Right photo; processing a group of German dead at Fosses-la-Ville Cemetery # 2.

One particularly day, the casualties kept coming and coming and coming and we didn’t stop until those boys were properly identified, processed and buried. They said we set a record that day for processing and burying 405 First and Third US Army servicemen. I remember feeling proud, exhausted and sad all at the same time. We never discussed our “records”.

As from 8 November 1944, the 607th assumed full responsibility of operations at the H-C Cemetery.

While snow was still on the ground during the 1944-1945 winter, Captain Whitman Pearson was transferred from the 607th QM GR Co to ETOUSA Headquarters, and First Lieutenant Nicholas J. Sloane became our Company Commander (transfer took place after 14 December 1944 –ed).

As the fighting in the immediate area slowly came to an end, trips increased to locate casualties. Sometimes we would receive reports of possible locations of losses from military units operating and/or stationed in a particular area, and sometimes the reports would come from civilians. I remember even going into Holland, and later in Eastern Germany, to retrieve casualties. Sometimes we would find a soldier or a group of soldiers and they would still be lying as when they were hit. We figured the unit must have been moving fast to leave the bodies behind. At times we would find a soldier or a group of soldiers laid together, wrapped in their shelter half with their weapon vertically stuck in the ground to mark their location.

It was in Belgium that I began to be recognized as the 607th GR person that had a special knack for finding the remains of airmen in a downed airplane. It all started back in France. I was the driver of a group of guys that went to recover the remains of airmen in a crashed airplane. On these missions we would all share our knowledge or opinions about the type of aircraft and how many remains should be on that type of plane.

Some of the guys knew the location inside the wreckage where each person might be, pilot here, co-pilot over there, radioman here, gunners there, there and there, bombardier etc. Sometimes all or part of the plane’s crew had bailed out, sometimes all were still with the crashed plane. I listened and shared each time I was sent to drive on a recovery mission and I guess I learned more than I realized.

One day in Belgium, I was given coordinates and ordered to take a weapons carrier and 2 men with me to locate a reported downed plane. Lew Farrow never went with me on these missions, he usually continued our standard procedure. I hadn’t been out with these two guys before and when we located the crash site it was like most. I don’t remember the type of airplane but I know it was a bomber of some type with a crew of 5. It had impacted fairly hard and almost totally burned out, melting everything in the plane to almost unrecognizable parts. We looked at the totally destroyed and burned out plane and one of the guys said, looks like they all bailed out. I said no: “They’re all here, the five of them”. They both said: “Where”? So I explained to them where the location of each airman should be by their job on the plane and then verified they were in their position by the slightly darker color that the burned bodies left at their known position.

We scratched around in the suspected areas and usually recovered melted rings, small change, pocket knives, fingernail clippers, zippers, dog tags and teeth of the airmen (mainly objects that wouldn’t burn). We then placed them in individual Personal Effects Bags to be eventually turned in at the Operations Tent for identification. The only note we would make was the location in the plane where the individual remains were found. After returning to Henri-Chapelle Cemetery, the other guys told their Platoon Sergeant about the recovery, and he shared the story with his Platoon Leader and after that I was almost exclusively selected to drive to the report of a downed plane. If I had to guess, I believe I helped recover remains from 50 to 75 downed aircraft while with the 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company. Some of the wrecks were fighters, some were large bombers, some were small spotter planes and some were medium sized planes. Some were American, some were Allied and some were German. We treated them all the same. At the end of the war, when stationed in Berlin, I was detailed for a number of airplane wreckage searches in Poland. I was usually the only GR person along with a squad of infantry sent out in a deuce-and-a-half (2 ½-ton truck) to search for a reported crash site in order to recover the remains of any MIA personnel before Germany got divided between East and West.

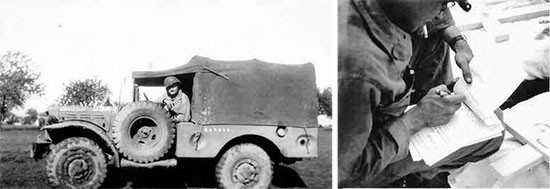

Left photo; Private First Class Kenneth J. Rehmer with Weapons Carrier (photo taken either at Fosses-la-Ville or Henri-Chapelle, end September 1944). Right photo; 607th QM GR Co serviceman completing Graves Registration Report No. 1 (Revised 1 Sept. 1943) designated “Report of Burial”.

I helped bury two soldiers I knew from Madison County, Arkansas. One was Corporal Norman Misenstead of Kingston, and the other was Junior Bayles of St. Paul. I picked Misenstead up very early in 1945 while doing the daily circle to the local Field Hospitals in Belgium. After the boys (wrapped in white sheets with a personal effects bag attached) were loaded on my truck and I was getting ready to move on to the next pick-up point, I always looked at the list of names of the boys I was hauling. I don’t really know why, I just did. While scanning the list, Kingston, Arkansas caught my eye and then I read the name. Norman and I were from the same little town and we knew each other enough to have traveled together in the states. Norman Misenstead had died from his wounds, after being hit the previous day. I was with him when we buried him at H-C Cemetery.

Later in March of 1945, I was at a processing point somewhere in Germany (this could have been at Euskirchen around 13 March 1945) when I saw Junior among a line of bodies. At first I thought it was my long time friend Irvin Bayles from St. Paul, but when I looked at the dog tags they said Marion Bayles, Jr. It was Irvin’s little brother Junior. Later that day, I drove the truck from Germany back to Henri-Chapelle with Junior in it and was present when we buried him. Forty years later during on of our 607th Reunions I learned that no other member of the 607th was known to have buried someone they knew. I found this odd because I had assisted in burying two people I knew. Was I the only one?

Once the First United States Army liberated Belgium, the countries of Belgium and the US would establish a very strong bond. I really didn’t understand that then, I just knew that once the city of Aachen, Germany, was captured and we pushed further into Germany we always brought our dead back to Belgium’s Henri-Chapelle Cemetery for burial. History records that the United States Congress had not authorized American soldiers to be buried on German soil (enemy territory), so our boys although killed in Germany, were buried in friendly and Allied soil in Belgium. Our Company was to remain almost five months at the H-C Cemetery before moving into Germany. Responsibility of Cemetery operations ceased officially on 31 March 1945.

Before leaving Belgium, the 607th QM GR Co established and/or conducted burial operations at the following cemeteries:

| Fosses-la-Ville | Henri-Chapelle | Overeupen (Germany) |

Germany:

I personally entered Germany at Aachen, the first German large city captured by the Allies after a five-week long battle (21 October 1944 –ed). At first the only change to the job was that as groups we were bivouacked in Germany and hauling casualties back to H-C Cemetery (in Belgium) instead of the 607th QM GR Co as a whole being bivouacked at Henri-Chapelle and venturing out on short missions into deserted obliterated ruins that had once been German strongholds.

Many of the Platoons’ assignments were for a short duration only. Small teams of men would be sent out to set up a Collecting Point for 1 up to 3 days, and go out to collect bodies. When other units would learn of our presence, they would bring their dead and even German civilians would sometimes bring either the dead bodies directly to our CP or would come to tell us where dead were located. If there was enough time, the initial processing for identification was carried out at the small CP. If not, the SOP was to collect the bodies and truck them back to the main Collection Point or the selected cemetery. When men were on an assignment for such a short period (1 to 3 days, as indicated), the main job was to collect bodies and not really do any processing. Being a driver, I mostly drove our ¾-ton weapons carrier. The daily trips were organized for purposes of disinterring isolated graves and returning the bodies to the cemetery for proper burial.

Establishing, collecting and burial operations at Henri-Chapelle Cemetery. Left photo; from L to R: Private Eugene R. Worley and Sergeant Elwain Crawford. Right photo: from L to R: Private First Class William L. Tollefson and Private Garland E. Robinson erecting wooden crosses.

As in Belgium, most of my time in Germany is a blur with the exception of ingrained memories.

I nevertheless remember my haul time increasing as a driver, and Lewis Farrow and I spent quite a bit of time driving from CPs near the front back to Henri-Chapelle. I also remember this is when we changed from driving mostly the weapons carriers with trailers, to heavier trucks with trailers. The ¾-ton weapons carriers with trailers hauled a maximum of 13 to 15, but the deuce-and-a-half with trailer could haul up to 150 bodies.

When a group of us got assigned to a front unit, immediately they liberated an enemy Concentration Camp. My memory plays tricks on me and now I think it may have been a Prisoner of War Camp. Although the images are ingrained in my memory, it amazes me that I really don’t remember simple details of the camp like its name. I do know that after I returned to Arkansas, US Army Criminal Investigation Division (operating under the US Provost Marshal General –ed) agents came to Kingston looking for me. You can imagine my thoughts when CIC agents driving a black government vehicle started asking the local Kingston people my whereabouts? After all, I had recently delivered a few loads of moonshine to Kansas City! As I sat in the passenger seat, with an agent in the driver’s seat and another agent with his portable typewriter in the back seat, it turned out that as a former 607th Graves Registration service soldier, they wanted my expert testimony about my opinion of the condition of the bodies. I was told by the agents that I might be called to testify at the Nuremburg Trials but I never heard from them again.

One day I picked up a downed pilot walking towards the rear. He told me he had been shot down in his small plane while spotting for the field artillery. It was good to have someone to talk with while returning to the rear. My load consisted of about 150 casualties with all their equipment and was quite heavy and as we approached a small hill my 2½-ton with trailer lugged down, the pilot asked me what I was hauling back to the rear that was so damn heavy? I simply said: “bodies”. He looked at me like I was joking and we kept talking. Later we stopped to stretch our legs when I saw him raise the canvas just enough to see a hand. He simply said: “Well I’ll be damned” and dropped the tarpaulin and started walking away. I yelled at him:“Hey, don’t you want to get back in”? He never said a word and just kept walking with his head down as I drove off past him.

We of course duly celebrated V-E Day (8 May 1945) but our job continued. The only change was in the location of the casualties. The boys weren’t so easily found at Hospitals, Collection Points or ongoing battlefields. There were approximately 29,000 American and Allied soldiers missing in action and our job became more of a search and recovery mission. We found a lot of our boys that had been buried in local German cemeteries, so we disinterred them and brought the bodies back to temporary cemeteries or returned them to Henri-Chapelle for identification and re-interment.

Winter operations at Henri-Chapelle Cemetery. Left photo; from L to R: Sergeant Michael B. Dimattia, Private Edward D. Gellenbeck, and Private James F. McWorther. Right photo; temporary wooden huts set up by 607th QM GR Co personnel near the Cemetery.

After we had completely left the Henri-Chapelle Cemetery and the 607th was now operating 100% in Germany, we were near Gießen. Farrow and I were assigned to go into the deserted town of Gießen each day with a weapons carrier and trailer and methodically go through the ruins searching for bodies. We would park our vehicle and Farrow would take one side of a street while I would take the other to search the ruins, even entering into the deserted levels of what were once city apartments or homes. We would work one block at a time and when we found a body, sometimes a German, sometimes an American or Allied soldier, mostly civilians, we would bring them to the street. After searching the block, together we would load the weapons carrier and trailer and move to the next block until we had a sufficient load. Some days we would make a number of trips back to the Collection Point and other days we would only make one trip. This searching continued for a long time.

One morning during formation, Platoon S/Sgt Norman L. Beadles asked for 2 volunteers for a mission. It was unusual to ask for volunteers, as we would normally be just assigned to a mission. I elbowed Lew Farrow and said let’s do it. Farrow indicated no but because we were in a somewhat boring routine, I elbowed him again. Farrow finally agreed and we raised our hands. Staff Sergeant Beadles bellowed; “Little – Farrow, report to Sergeant Bell”!

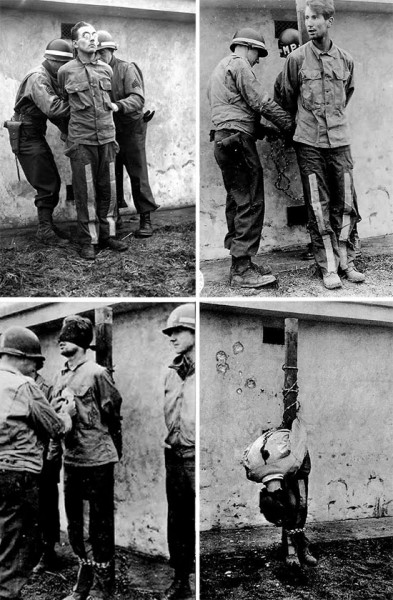

Sergeant Bell was a Section Leader in our (Second) Platoon and we were used to working with him. The NCO told us to get hold of a weapons carrier and be prepared to travel to Henri-Chapelle, Belgium, to witness an execution. We didn’t know what we were needed for but did what we were told. Sgt. Bell had his own vehicle and we were off. When we arrived I remember thinking we must be late because there was quite a gathering of brass, Military Police and photographers and immediately after Sgt Bell reported, orders were given to bring out the prisoners. Sergeant Bell, Farrow and I were ordered back while the MPs brought out the three prisoners and prepared them for execution.

I then witnessed the execution of 3 German soldiers by a firing squad near Henri-Chapelle. They had been caught wearing American uniforms while trying to infiltrate our lines in a captured American jeep. The first three PWs had been captured near Aywaille on 17 December 1944. Tried as spies on 21 December they were sentenced to death by firing squad. The execution took place at Henri-Chapelle 23 December 1944 (2 more were tried and executed on 26 December; 7 others on 31 December, and 3 more on 13 January 1945, the latter were not executed at the H-C Cemetery, but at Huy, Belgium; the first 3 spies were Manfred Pernass, Günther Billing, and Wilhelm Schmidt, all members of 5. Kompanie, 12. Fallschirmjägerregiment. Their bodies were later transferred to Lommel German Military Cemetery, Belgium –ed).

My memory of the execution is that after they were tied to the post, they were comforted by Colonel P. Schroder (FUSA Chaplain), then blindfolded and quickly the command was given to fire. Captain J. Eiser (633d Med Clr Sta –ed) pinned the white target patches on the prisoners).

I remember, three specific things about the execution:

- One of the Military Police personnel that were part of the firing squad yelled to “Turn’ em loose and let’ em run”! I imagine he would feel better about shooting him if he was running.

- Just before the command to fire was given, one of the prisoners yelled “Heil Hitler”.

- After the execution, one of them was still moving and the coroner applied pressure to his neck. I guess the pressure was applied to his corroded artery finishing him off.

The photographers took pictures of one of the MPs and Sgt. Bell cutting one spy down from the pole, then the press and the rest of the crowd left. Farrow and I moved in and helped the Sergeant with the other two. Today, I still don’t understand our involvement because all we did was remove the prisoners from the posts and load them onto our weapons carrier. After lunch we processed them for burial and took them to the German sector of the H-C Cemetery.

We then turned them over to the Graves Registration personnel there and left. Why didn’t the Graves Registration people stationed at Henri-Chapelle handle them?

Later I saw the press photos of the execution I witnessed in the “Stars and Stripes” dated June 17, 1945 and cut the article out and saved it for posterity. The three German spies that I saw executed were Manfred Pernass, Günther Billing, and Wilhelm Schmidt (Sergeant Bell’s photo was in the Stars and Stripes too).

What I mostly remember about the summer of 1945 was the condition of the dead. I must say that the smell of the decomposing bodies especially during hot weather was overpowering and unforgettable. Seldom were masks or rubber gloves available and a day’s work would leave each of us covered in blood. Clothes had to be washed in gasoline or thrown away because of the stench. Therefore we worked without shirts as much as possible to save our clothes.

Execution by firing squad of Germans caught wearing American uniforms following the outbreak of the enemy counter-offensive in the Belgian Ardennes. Following trial on December 21, the enemy PWs were executed near Henri-Chapelle Cemetery December 23, 1944 and their bodies processed by members of the 607th QM GR Co. More prisoners were tried and executed respectively on December 26, December 31, 1944, and January 13, 1945.

After the 607th QM GR Co moved onto German soil and before the Company began disbanding, our men established and/or conducted burial operations at the following cemeteries:

| Ittenbach | Breuna | Eisenach |

Movements Germany – Second Platoon, 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

1 April 1945 > Ittenbach, Germany

10 April 1945 > Breuna, Germany

23 April 1945 > Eisenach, Germany

Organization – Second Platoon, 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

Commanding Officers

First Lieutenant Ernest J. Terry, QMC, Platoon Leader, Second Platoon

First Lieutenant John A. Liddie, QMC, Platoon Leader, Second Platoon (replaced above CO)

Attachments